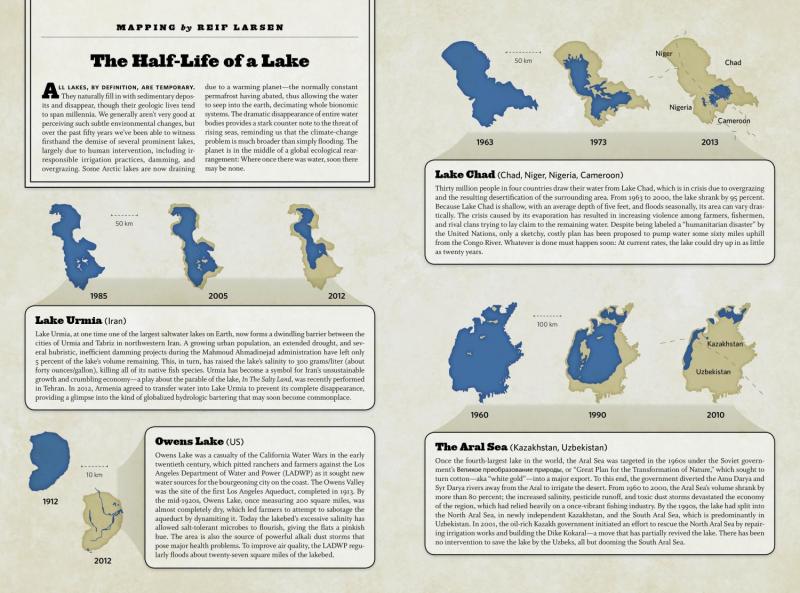

All lakes, by definition, are temporary. They naturally fill in with sedimentary deposits and disappear, though their geologic lives tend to span millennia. We generally aren’t very good at perceiving such subtle environmental changes, but over the past fifty years we’ve been able to witness firsthand the demise of several prominent lakes, largely due to human intervention, including irresponsible irrigation practices, damming, and overgrazing. Some Arctic lakes are now draining due to a warming planet—the normally constant permafrost having abated, thus allowing the water to seep into the earth, decimating whole bionomic systems. The dramatic disappearance of entire water bodies provides a stark counter note to the threat of rising seas, reminding us that the climate-change problem is much broader than simply flooding. The planet is in the middle of a global ecological rearrangement: Where once there was water, soon there may be none.

Lake Urmia (Iran)

Lake Urmia, at one time one of the largest saltwater lakes on Earth, now forms a dwindling barrier between the cities of Urmia and Tabriz in northwestern Iran. A growing urban population, an extended drought, and several hubristic, inefficient damming projects during the Mahmoud Ahmadinejad administration have left only 5 percent of the lake’s volume remaining. This, in turn, has raised the lake’s salinity to 300 grams/liter (about forty ounces/gallon), killing all of its native fish species. Urmia has become a symbol for Iran’s unsustainable growth and crumbling economy—a play about the parable of the lake, In The Salty Land, was recently performed in Tehran. In 2012, Armenia agreed to transfer water into Lake Urmia to prevent its complete disappearance, providing a glimpse into the kind of globalized hydrologic bartering that may soon become commonplace.

Owens Lake (US)

Owens Lake was a casualty of the California Water Wars in the early twentieth century, which pitted ranchers and farmers against the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) as it sought new water sources for the bourgeoning city on the coast. The Owens Valley was the site of the first Los Angeles Aqueduct, completed in 1913. By the mid-1920s, Owens Lake, once measuring 200 square miles, was almost completely dry, which led farmers to attempt to sabotage the aqueduct by dynamiting it. Today the lakebed’s excessive salinity has allowed salt-tolerant microbes to flourish, giving the flats a pinkish hue. The area is also the source of powerful alkali dust storms that pose major health problems. To improve air quality, the LADWP regularly floods about twenty-seven square miles of the lakebed.

Lake Chad (Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon)

Thirty million people in four countries draw their water from Lake Chad, which is in crisis due to overgrazing and the resulting desertification of the surrounding area. From 1963 to 2000, the lake shrank by 95 percent. Because Lake Chad is shallow, with an average depth of five feet, and floods seasonally, its area can vary drastically. The crisis caused by its evaporation has resulted in increasing violence among farmers, fishermen, and rival clans trying to lay claim to the remaining water. Despite being labeled a “humanitarian disaster” by the United Nations, only a sketchy, costly plan has been proposed to pump water some sixty miles uphill from the Congo River. Whatever is done must happen soon: At current rates, the lake could dry up in as little as twenty years.

The Aral Sea (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan)

Once the fourth-largest lake in the world, the Aral Sea was targeted in the 1960s under the Soviet government’s Великое преобразование природы, or “Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature,” which sought to turn cotton—aka “white gold”—into a major export. To this end, the government diverted the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers away from the Aral to irrigate the desert. From 1960 to 2000, the Aral Sea’s volume shrank by more than 80 percent; the increased salinity, pesticide runoff, and toxic dust storms devastated the economy of the region, which had relied heavily on a once-vibrant fishing industry. By the 1990s, the lake had split into the North Aral Sea, in newly independent Kazakhstan, and the South Aral Sea, which is predominantly in Uzbekistan. In 2001, the oil-rich Kazakh government initiated an effort to rescue the North Aral Sea by repairing irrigation works and building the Dike Kokaral—a move that has partially revived the lake. There has been no intervention to save the lake by the Uzbeks, all but dooming the South Aral Sea.