During the fall of the Ming Dynasty in seventeenth-century China, as Manchu armies swept in from the north, court artists and scholars confronted a painful choice: align with the invading forces, or remain loyal to the old guard and face death or exile. Some Ming loyalists killed themselves rather than pledge themselves to the nascent Qing Dynasty. Others became Buddhist monks and wanderers who roamed the countryside, painting large narrative works that depict melancholic journeys across infinite-seeming landscapes.

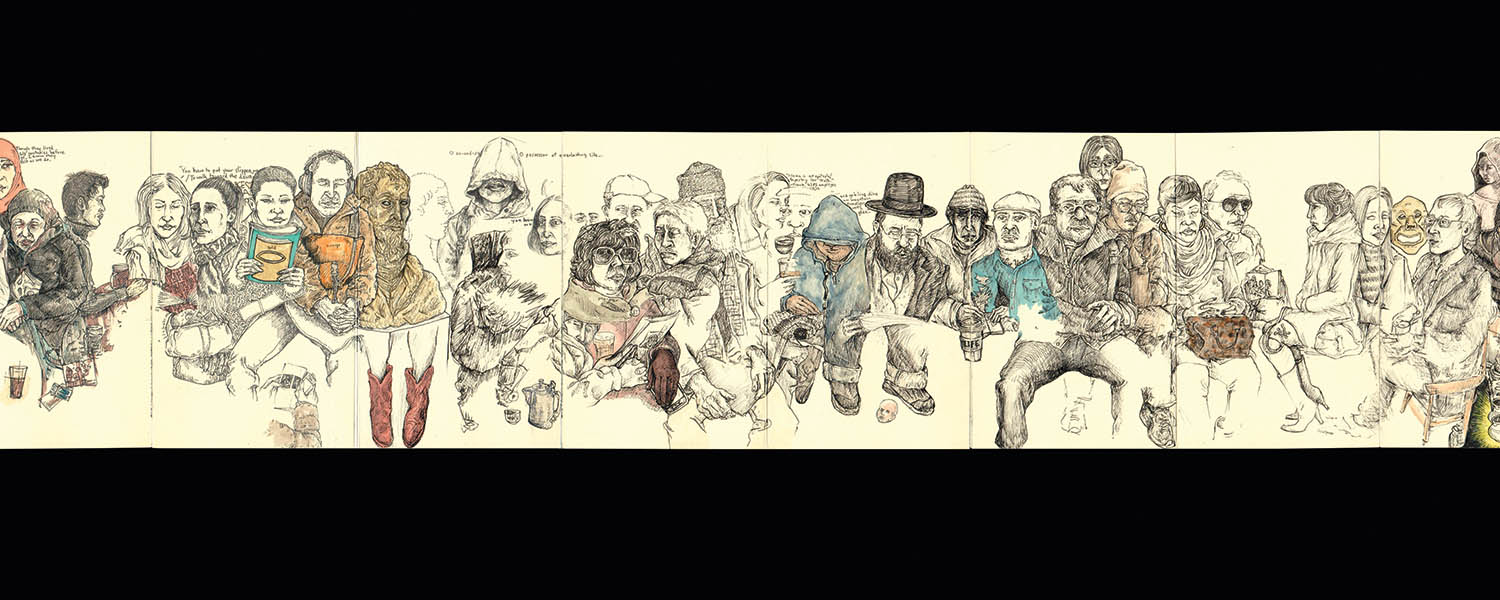

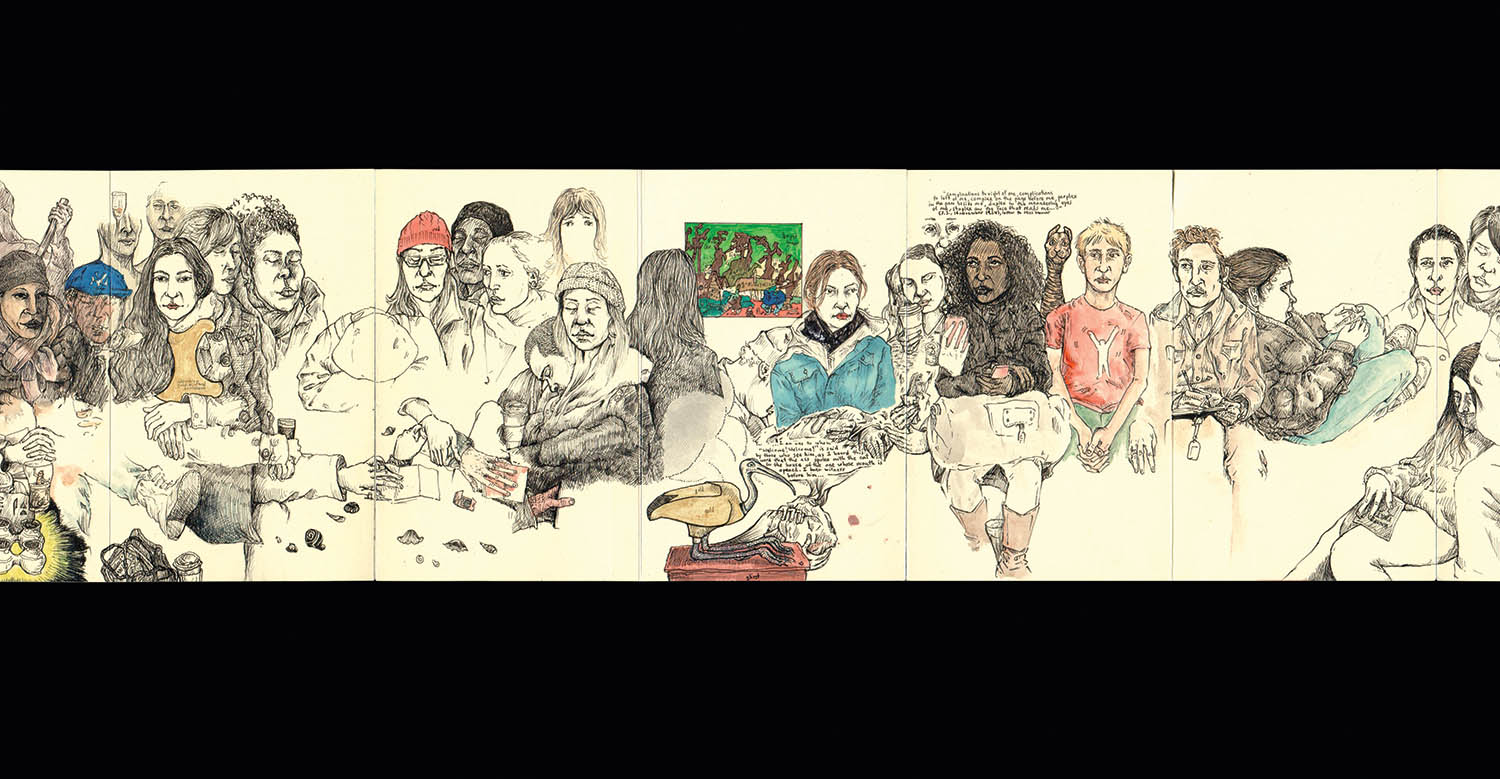

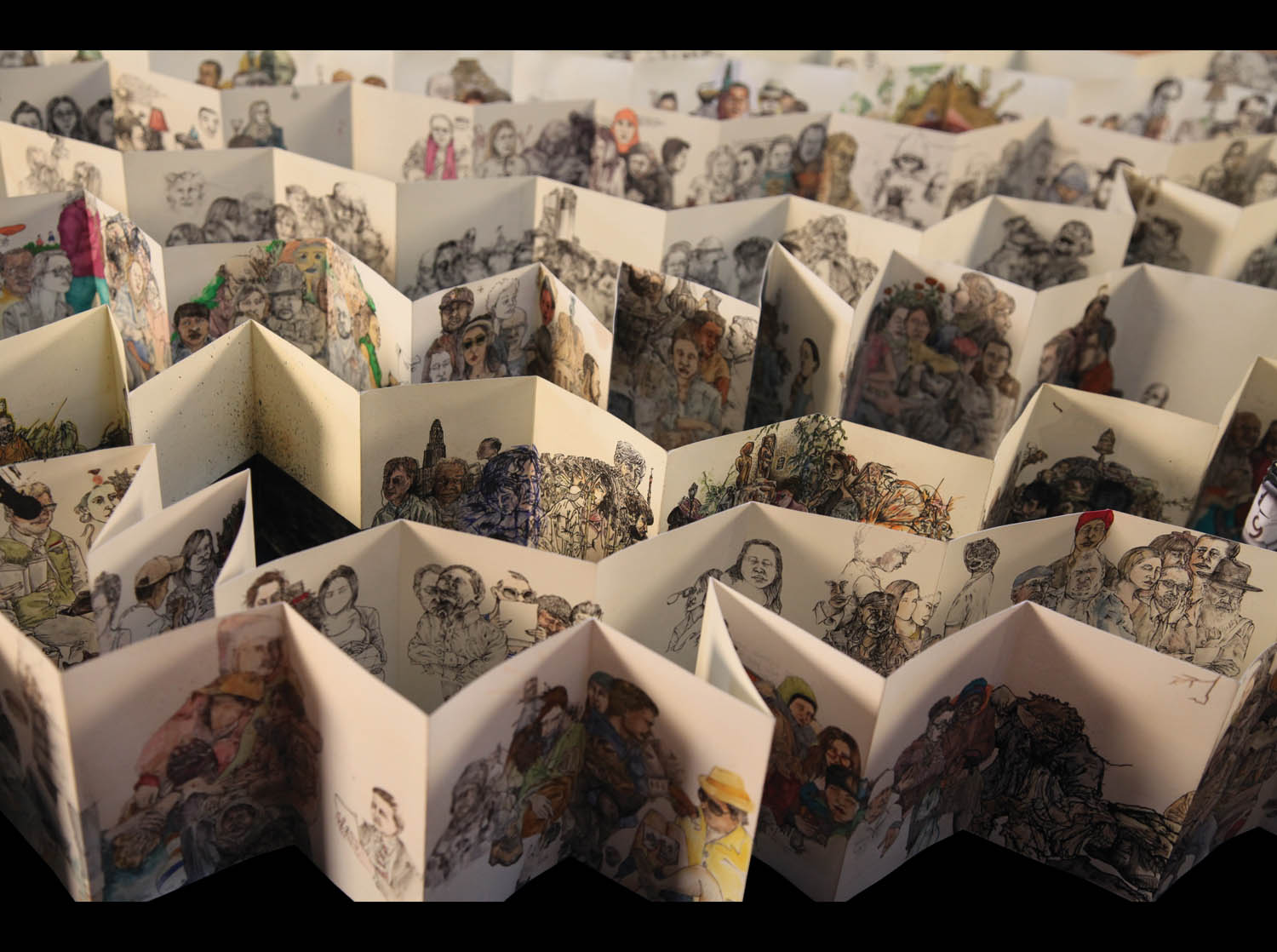

These paintings have long been a source of fascination for the American illustrator Chris Russell, and they’re the inspiration for his project of the last nine years: a series of figurative ink drawings that unfold across pocket-sized accordion notebooks, each measuring five and a half inches tall and more than one hundred and eight inches long when fully extended. He now has nine such notebooks, which merge into a seamless stream of interlocking images when placed end to end. Once, Russell found a particularly long hallway and laid out all the notebooks across the floor. The work in progress stretched over eighty-one feet. “It was a little overwhelming,” he says.

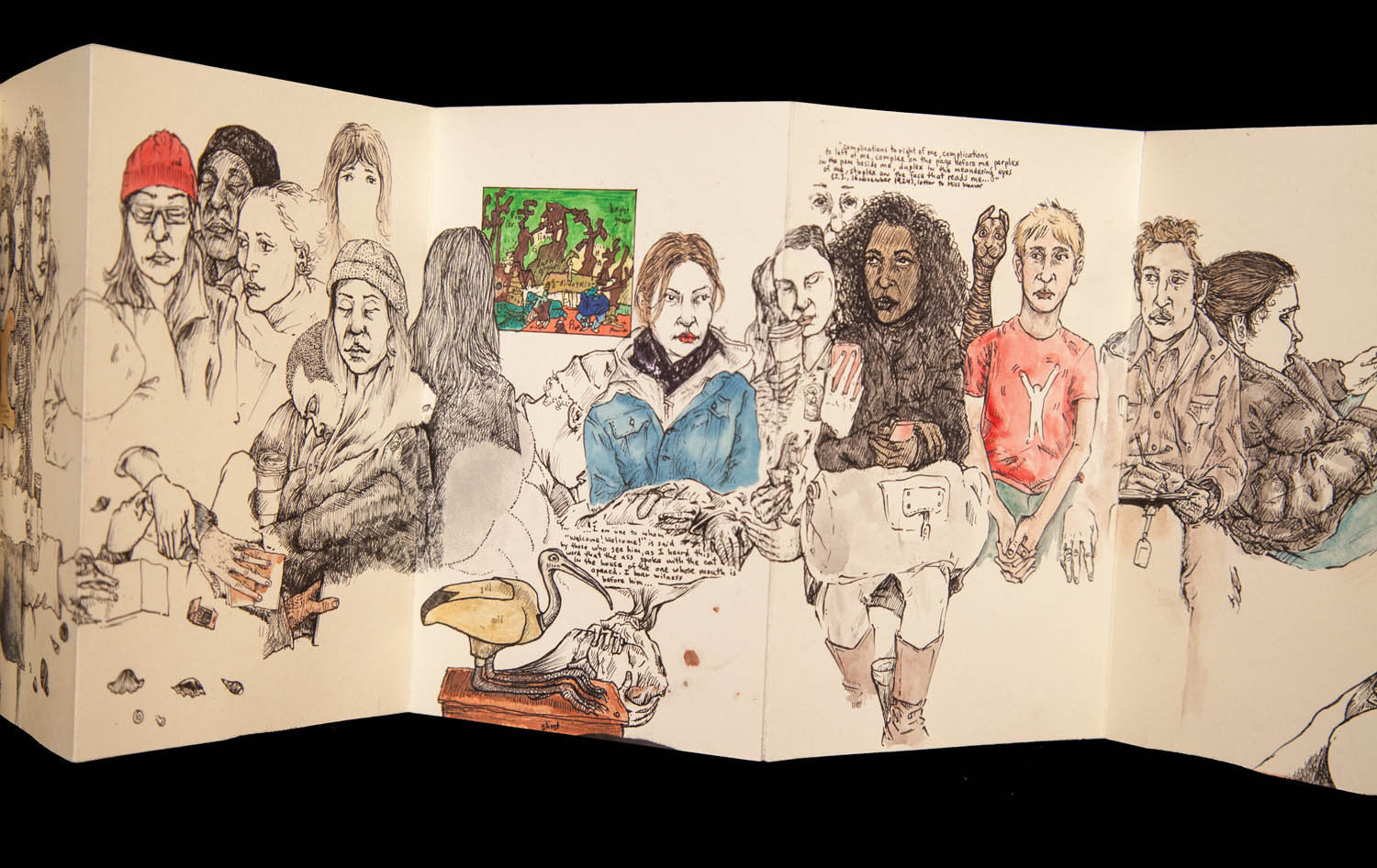

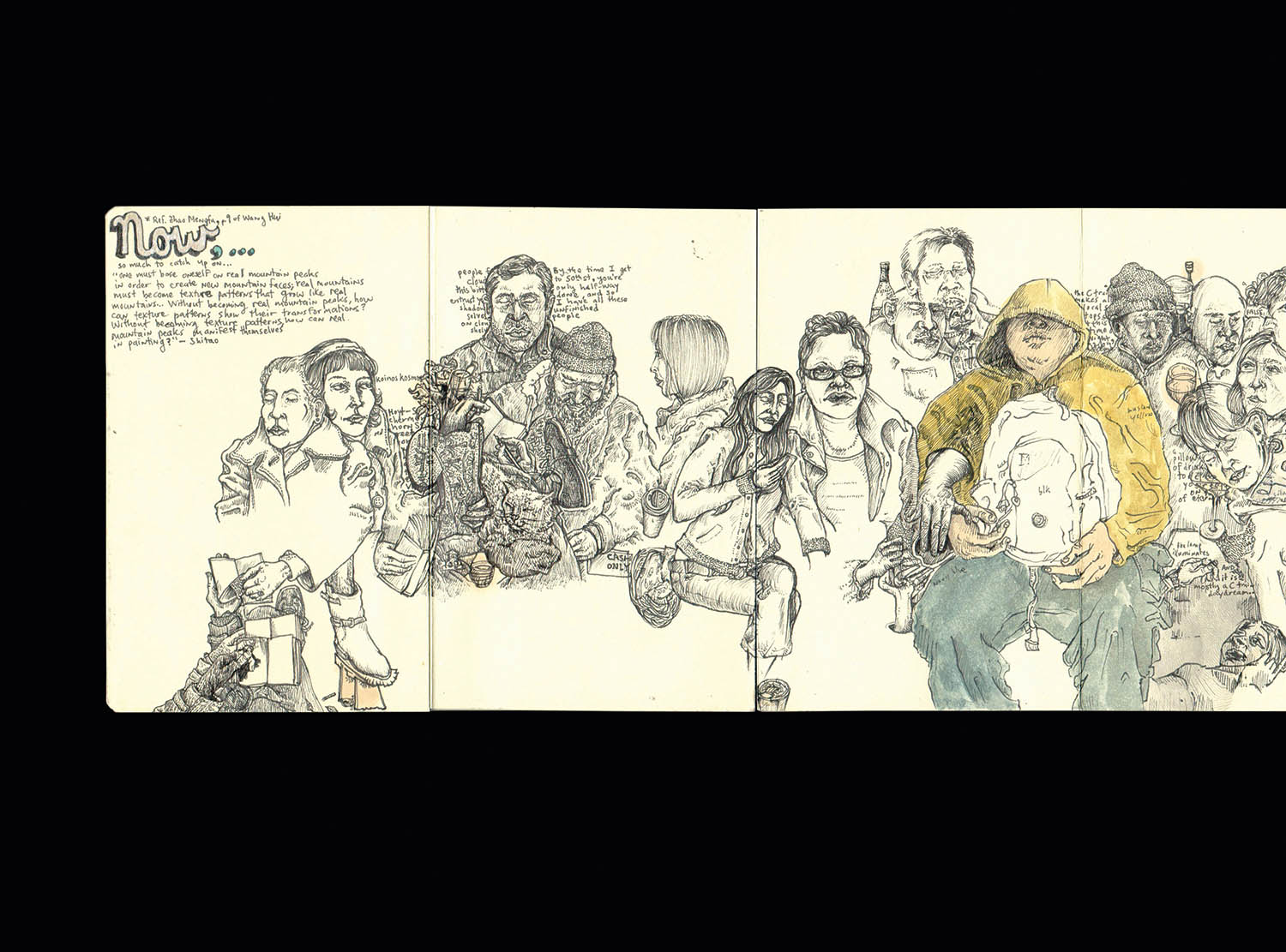

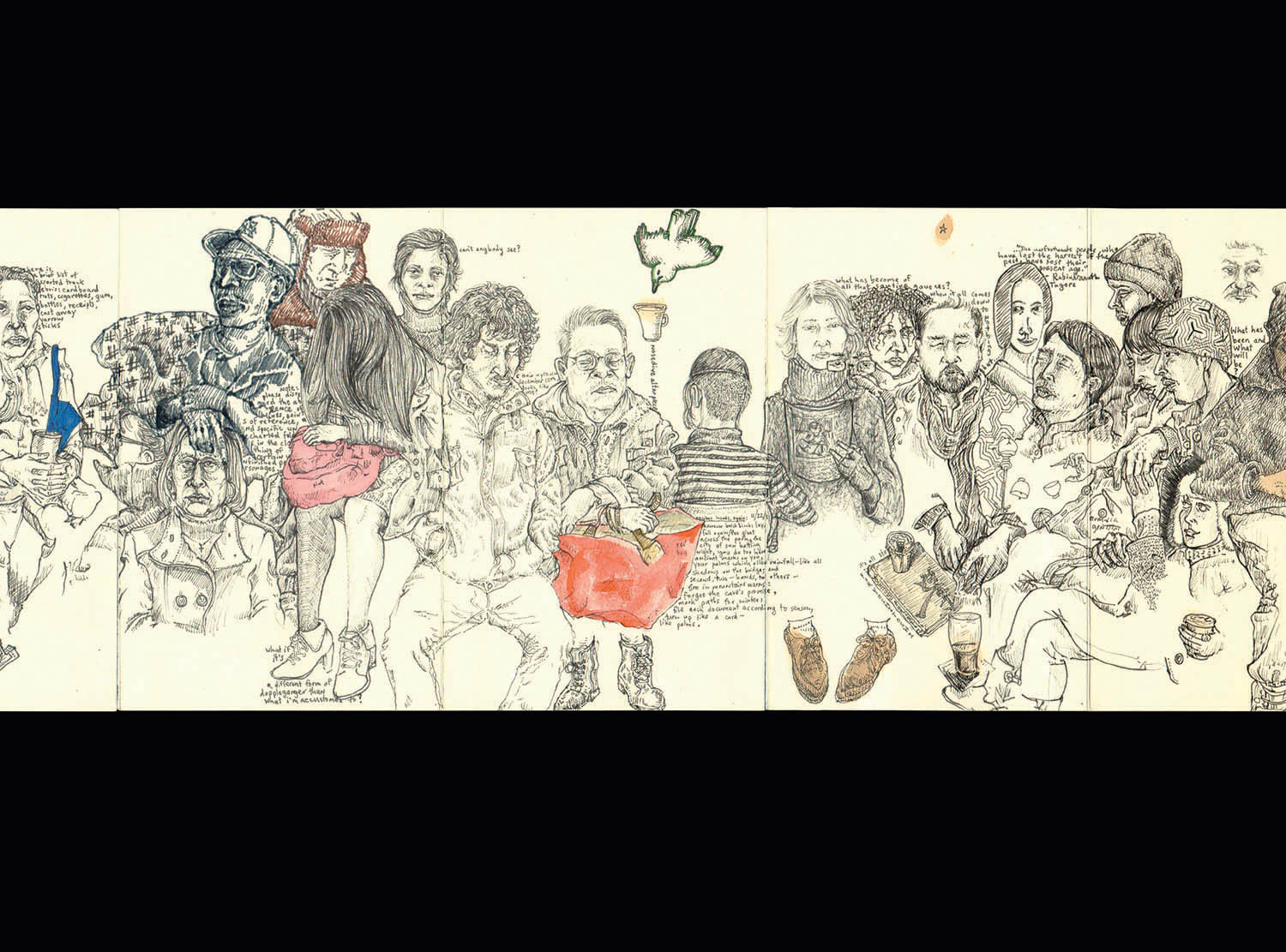

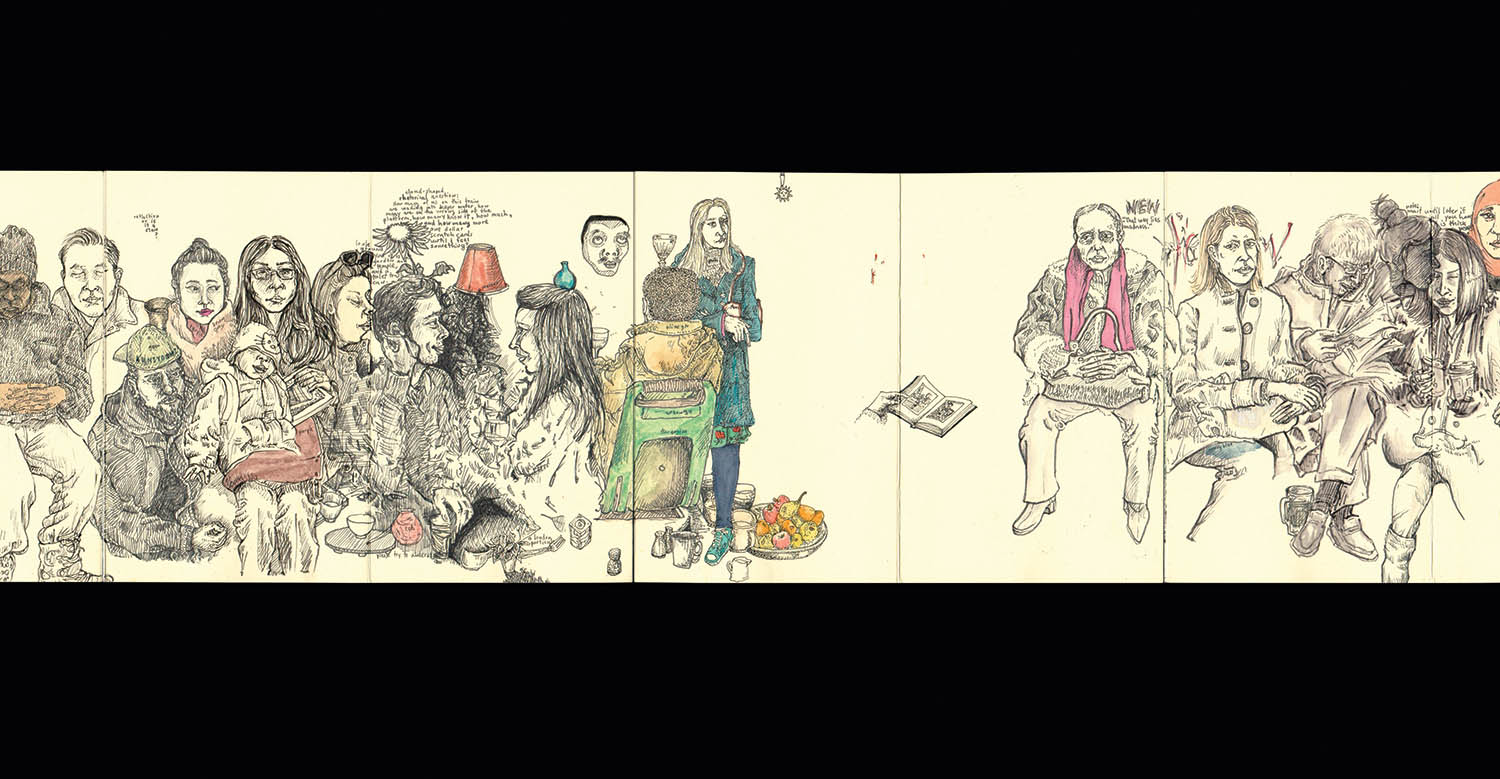

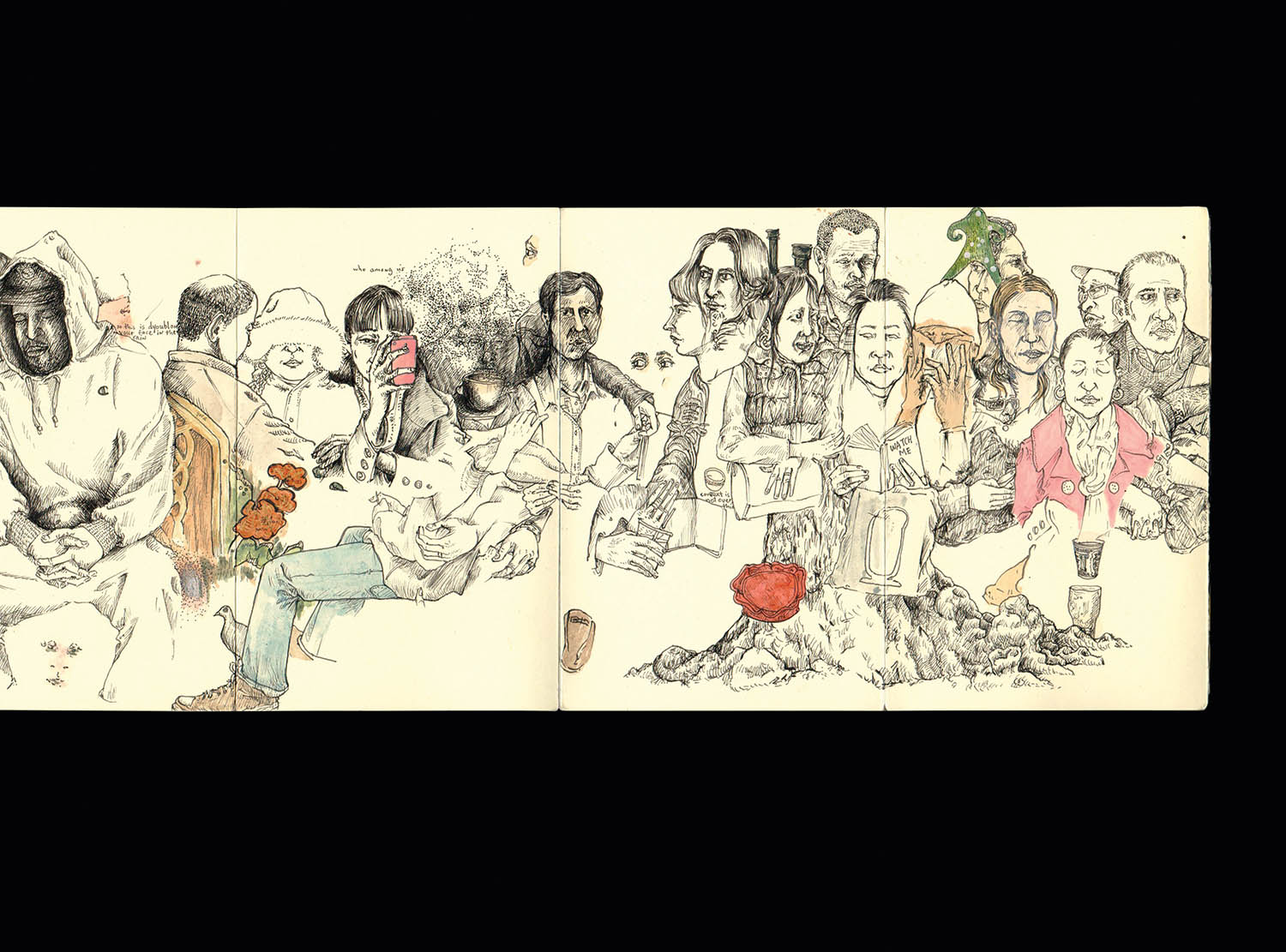

Russell refers to his work as an “endless landscape” in a nod to the late Ming / early Qing compositions, particularly the masterful, elegiac work of Shitao, Kuncan, and Xiao Yuncong. When you relax your gaze, Russell’s images take on the flowing topographical patterns of the paintings they’re modeled after: clusters of form that rise into peaks between swathes of blank space suggesting clouds or sky or rising mist. On closer look, Russell’s drawings resolve into intimately detailed portraits of the strangers who sit opposite him during his daily commute across New York City. They evoke not only the form but the feeling of the Chinese landscape paintings, that melancholic sensibility. “Portraiture is inherently melancholic,” he says. “It’s about trying to hold onto something that you know is gone already, or that you know is about to be gone.”

The accordion notebooks also narrate a journey, a visual diary Russell has kept in the interest of maintaining a portable daily art practice. Scanned from left to right, the images serve as a record of Russell’s travels and experiences, with references to museum exhibitions, rock concerts, meals with friends. They reveal the city’s shifting demographics as he rides different subway lines throughout Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. They also chart the passage of time: Seasons change as his subjects add and subtract layers of clothing; technology changes as smartphones become ubiquitous in the later volumes.

Russell draws from life, not memory. “What you’re seeing in the drawing is whatever was in front of me at that time,” he says. The most obvious challenge of drawing strangers on a moving train is that they may leave at any moment. When they do, Russell says he tries to “finish the thought,” but he doesn’t attempt a wholesale re-creation of what’s no longer there. As a consequence, many of his portraits are unfinished: figures ghost into blankness, or into other figures. Noses, lips, and hands float disembodied through space; a pair of legs in half-laced boots vanishes where the knees should be. One face features a painstakingly detailed beard but lacks eyes and a nose. This lends the work a surreal, haunted quality. (In a spin-off project he calls “Subway Ghosts,” Russell sketches riders on transparency paper. Once his subject has left the train, he holds up the sketch in the exact position where that person was sitting and photographs it.)

Russell draws from life, not memory. “What you’re seeing in the drawing is whatever was in front of me at that time,” he says. The most obvious challenge of drawing strangers on a moving train is that they may leave at any moment. When they do, Russell says he tries to “finish the thought,” but he doesn’t attempt a wholesale re-creation of what’s no longer there. As a consequence, many of his portraits are unfinished: figures ghost into blankness, or into other figures. Noses, lips, and hands float disembodied through space; a pair of legs in half-laced boots vanishes where the knees should be. One face features a painstakingly detailed beard but lacks eyes and a nose. This lends the work a surreal, haunted quality. (In a spin-off project he calls “Subway Ghosts,” Russell sketches riders on transparency paper. Once his subject has left the train, he holds up the sketch in the exact position where that person was sitting and photographs it.)

Scattered throughout these human landscapes are odds and ends Russell has observed elsewhere: a samurai suit from an armor exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the torn corner of a postage stamp, light bulbs, lizards, an entire David Hockney painting tucked behind the slouched bodies of commuters. Russell says he wants to create a sense of “altogetherness” in his work by setting “mundane, everyday forms next to things that are highly numinous and powerful.” He’s especially interested in vessels: coffee mugs and wine glasses, Chinese bronzes, Mayan pots, empty cans, and above all people, those vessels containing the complex substrate of their own subjectivity.

Many of the seventeenth-century Chinese landscape paintings pay homage to the dongtian (grotto-heaven) folktales of Daoist cosmology, particularly fifth-century poet Tao Yuanming’s fable “Peach Blossom Spring.” In this story, a fisherman lost on a river passes through the mouth of a cave to discover an idyllic village frozen in time. He learns that the villagers have lived in complete seclusion since the age of their ancestors, blissfully unaware of the turmoil of the outside world. In another dongtian legend Russell references, a wanderer enters the realm of immortals through an enchanted cave. He stays for a little while—a few days or a week. Then he decides to leave the cave and return to his family, but when he arrives at his village, he discovers that hundreds of years have gone by in his absence. When he tells the villagers his story, everyone dismisses him as mad. In desperation, he returns to the cave, only to find the entrance sealed.

When Russell was beginning his notebooks, he often thought of these stories, not only because they’d inspired so many of his favorite paintings, but because of the way the legends evoke places that exist outside of society and time, which seemed to cohere with the world of his own underground commute. The subway system is transitional and interstitial. It has no stable population and no clear character; it’s less a place in its own right than a means of arriving at one. Within the democratized and compressed space of the subway car, social categories lose their meaning, as do the boundaries individuals might otherwise maintain around their bodies. If you, like Sartre, believe “Hell is other people,” then a crowded subway car is surely one of its inner rings. During the rush-hour crush, everyone is packed together in an involuntary embrace: high-speed traders and cashiers, lawyers and teenagers, psychiatrists and cheese mongers, buskers and hustlers.

In spite of this, or because of it, anonymity generally prevails. The more one feels the encroachment of strangers’ bodies on one’s own, the deeper the mind tends to retreat—an act of preservation, a way of forging space for the self. “I am not reduced to an ‘any body’ in the corridor of the subway station,” the French philosopher Luce Irigaray wrote. “My interiority, my intention remain my own in spite of the crowd.”

It is a testament to Russell’s prodigious skill, empathy, and attention that even as he draws a landscape of bodies flowing endlessly into one another, his portraits capture the sense of each subject’s own contained interiority. Their bodies may be present but their faces—sleeping in slack repose, or staring absently into the middle distance—make clear their minds are somewhere else entirely. We can’t know what they’re dreaming or thinking, but as Russell draws us into his act of witness, we’re compelled to ask and to recognize that within each of these figures another entire narrative exists.

“Still, the other—he or she—can look at us,” Irigaray wrote. “And it is important for us to be able to wonder at him or her even if he or she is looking at us. Overcome the spectacle, the visible, make a place for us to inhabit, a reason and a means of moving, a way of stopping ourselves, of going forward or backward through wonder.”

Chris Russell’s work is kinetic: To see it we have to hold and unfold it. We have to walk down a very long hallway to experience it in its fullness, all the time moving forward and backward through wonder.

—Ariel Lewiton