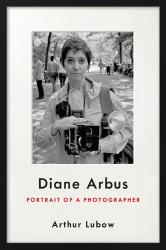

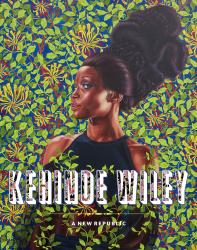

What kind of energy do we get from the streets? What does it give us and how much do we need it? The publication of Arthur Lubow’s biography, Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer, and a national tour of Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, a career retrospective of the artist’s work organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2015,* highlight how certain artists are able to tap into street energy, and what they extract from it.

What kind of energy do we get from the streets? What does it give us and how much do we need it? The publication of Arthur Lubow’s biography, Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer, and a national tour of Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, a career retrospective of the artist’s work organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2015,* highlight how certain artists are able to tap into street energy, and what they extract from it.

Lubow’s biography has drawn considerable attention for some of its revelations about Arbus’s chaotic personal life, including an incestuous relationship with her brother, poet Howard Nemerov. But the book is at its best when exploring how specific photographs came about.

Arbus started as a fashion photographer in 1948, working with her husband, Allan, on assignments for the likes of Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. He was the shutter man, she was the stylist. And she despised it. As Allan would later acknowledge, hers was “a very subservient role. It was demeaning to her, to have to run to these gorgeous models and fix their clothes.” Years later, in 1967, Arbus made clear there was more to it than that. “I hate fashion photography because the clothes don’t belong to the people who are wearing them,” she said. “When the clothes do belong to the person wearing them, they take on a person’s flaws and characteristics, and are wonderful.”

Lubow pinpoints a European vacation in 1951–52 as the moment when Arbus began “flexing [her] muscles” as a street photographer, although she wouldn’t make the professional break from her husband until a few years later, and she was never able to completely escape her photographer-for-hire role, including the occasional fashion shoot.

For Arbus, “street photography” didn’t mean candid shots of street scenes taken without the knowledge of their subjects, in the manner of Eugène Atget or Henri Cartier-Bresson. She may have tried that approach initially, snapping her shutter from afar and later cropping her images to “simulate intimacy.” But this trick didn’t satisfy her for long.

“Psychological need,” Lubow explains, “had drawn her to photography: the desire not only to see but to be seen… . [S]he wanted to get as close as she could to the people she was photographing and convert them into collaborators.” The trouble for Arbus—which, according to Lubow, played a significant role in her eventual suicide—was that her need was so intense. Her hunger for this “mutual seduction” stemmed, at least in part, from an inability to understand certain fundamentals of human exchange. (“What do people mean when they say they are close?” she once asked her psychotherapist.)

Arbus’s photo shoots did trigger a genuine bond between her and her subjects. “People were interested in Diane, just as interested in her as she was in them,” remarks curator John Szarkowski, a champion of her work in the 1960s. Still, her photographs—with their mix of perception, projection, and, some would say, exploitation—didn’t exactly speak of comforting human connection. In some cases—Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962 is one—she found her own unhappy state of mind staring right back at her.

Colin Wood, the agitated seven-year-old boy in Child, is rigid with fury. His eyes are lunatic-wide and his mouth is a distorted rictus. His contorted facial expression is in zany contrast to the dainty outfit he’s wearing: lederhosen-like shorts, a patterned shirt with a Peter Pan collar. The image was chosen from one of eleven frames. In the others, the boy more often “pranced, smirked and clowned for the camera.” But the shot Arbus selected tapped into something deeper. Speaking with Lubow in 2012, Wood revealed that his wealthy Park Avenue parents were going through a divorce at the time, and that he’d been left very much to his own devices. “He was living primarily on powdered Junket straight from the box, and the diet of sugar added fuel to his manic rage,” Lubow tells us. “At his progressive Catholic school, he brought toy guns to class and threatened to kill the other children.”

While some viewers might see Arbus as taking advantage of a boy’s emotional plight, Wood recalls feeling a real sense of connection with her: “She saw in me the frustration, the anger at my surroundings, the kid wanting to explode but can’t because he’s constrained by his background… . She’s sad about me. ‘What’s going to happen to him?’ What I feel is that she likes me. She can’t take me under her wing but she can give me a whirl.”

Thus, the image serves as a voice for the boy. It also, unmistakably, vented something in Arbus, almost erasing the boundary between them. Indeed, a recurring theme in Lubow’s book is the way Arbus either brazenly or unconsciously ignored most social and sexual boundaries and protocols. This disregard for the usual proprieties could crop up in casual queries, such as when, upon rendezvousing with an editor, she inquired, “You don’t want to go to an orgy, do you?” (The editor opted for a nice Italian dinner instead, though they did end up in bed together.)

“Simply crossing the fence of decorum didn’t satisfy her,” Lubow writes. “She needed her trespass to provoke a response, and her photographic portraits and sexual assignations were alternative ways of achieving affirmation that she was alive and real.”

In some shots—Mexican dwarf in his hotel room, N.Y.C. 1970 is the best example—“provocation” came closer to an odd sense of normalcy in a setting where you wouldn’t expect to find it. Arbus’s subject, Lauro Morales, has an easy air of sensual relaxation about him. The photo-

graph is consistent with her fascination with the carnivalesque. Yet the fond, languid gaze of Morales is as familiar as any satisfied lover’s.

Whether Morales and Arbus had an actual tryst is unknown, but in shooting subjects in a state of undress (as Morales was), Arbus sometimes went naked herself as a way of putting some literal skin in the game and encouraging her models to open up to her. No matter how far from the societal mainstream the people in her photographs were—freak-show performers, nudists, drag queens, and prostitutes—all barriers between them and the camera seemed to come down. The raw-nerve candor that energized her work also made it something new.

The sights on the streets of New York invigorated her. Lubow writes: “She surveyed the human exhibits with a child’s glee and a taxonomist’s sophistication. ‘People are gardens,’ she once told her goddaughter.” Her editor at Esquire, John Berendt, saw a strange contradiction at play in her: “Diane was delightful, very gentle, friendly, benign, but her eyes would light up at the mere suggestion of oddity, deformity, depravity.”

She was alert, as many journalists are, to the element of manipulation involved in drawing people out and getting them to give her what she was after. For some this is nothing more than a professional ploy. For Arbus it could verge on a primal exchange, triggered by psychic imbalance and appetite.

Arbus, in her frank, guileless way, put it best: “I do what gnaws at me.”

The same might be said of Kehinde Wiley, although in an utterly different context and manner. His work contains elements of historical homage and social commentary, especially on racial matters, that are absent from Arbus’s. And, of course, his media—primarily large oil paintings, but also stained glass and sculpture—provide a lushness that contrasts with the sometimes stark black-and-white of Arbus’s photographs.

Born in 1977 and raised in Los Angeles, Wiley attended art classes at the encouragement of his mother. When, on a class trip, he visited the Huntington library and gardens, with its collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century British portraits, it proved a watershed experience for him.

“South Central Los Angeles was not a very beautiful place then, and I think painting functioned as an interesting site of fantasy, in a way,” he says in Jeff Dupre’s Kehinde Wiley: An Economy of Grace, a documentary showing at the retrospective that offers keen insight on what “gnaws” at the African-American artist.

As Wiley plunged enthusiastically into that fantasy world, he quickly discovered his own painterly talents for it, while also becoming aware of something that disquieted him. “Oftentimes we think about the exotic as something that’s far away,” he tells Dupre. “When I watch television or participate in the media culture in America, sometimes the way that I’ve seen black people being portrayed in this country feels very strange and exotic because it has nothing to do with the life that I’ve lived or the people that I’ve known.”

Wiley’s corrective to this is to recreate masterpieces and touchstones from the Western art canon, substituting contemporary African-American figures for the Italian, Dutch, French, and English aristocrats or power players who sat for the originals.

At first glance, Wiley’s aesthetic sensibility seems far removed from Arbus’s. His canvases are often vast and symphonic in scale, where her photographs read more like small, astringent chamber works. Wiley’s paintings project an extroverted pageantry, thanks in part to their elaborately patterned backgrounds; Arbus’s photographs, meanwhile, reveal private worlds sparely observed.

Wiley makes a handsome living from his work, fetching prices between $65,000 and $250,000 for a single painting. Arbus, at the height of her fame in her lifetime, was lucky to get $75 for a print sold to a museum. He’s a business-savvy showman, with studios in New York and Beijing, and a bevy of assistants to help him. Arbus did have help in the darkroom from her husband and his assistant, even after she and Allan separated—but theirs was a small-time operation, not a cottage industry.

Yet when it comes to enlisting their subjects, there are striking parallels between Arbus’s methods and Wiley’s. His “street casting” technique, as he calls it, seems as instinctive and erotically charged as hers. Like Arbus, he seeks his subjects on the streets of New York, usually Harlem or Brooklyn, and talks to them extensively before taking photographs of them that serve as a basis for his paintings. Like Arbus, he makes them his collaborators, encouraging them to match the spirit of the classic European oil-on-canvas they’ll be “starring” in and subverting. Under his directions, his subjects strike the swaggering poses of warriors (Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, based on Jacques-Louis David’s 1801 painting Napoleon Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at St. Bernard Pass) or become preening dandies (Portrait of Andries Stilte, after Dutch painter Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck’s 1639–40 portrait of a member of the Harlem civic guard).

In each portrait, Wiley’s steady orchestral command is unmistakable, and his models clearly wield a degree of control in his work as well. “Much of my painting has been about the sitter deciding how they want to be seen,” he says in Dupre’s documentary.

In his early work, he made a point of reminding his models—all male—that they were going to be in a painting and that they should dress for the occasion. They obliged him—in New York street fashion. In Morpheus, for instance, based on Jean-Antoine Houdon’s 1777 sculpture, Wiley’s model—jeans sliding down from his hips, red-plaid boxers showing, gold bling hanging from his neck—is a somnolent-impudent usurper of a pose that, two and a half centuries ago, could never have been his. There’s an element of humor and fantasy in these images. But there’s also some powerful role reversal at work. A liberating truth emerges from them, too, as Wiley catches the essence of his models’ personalities—and, in the process, expresses something about himself.

“Why black men? Why men of color?” he asks himself in An Economy of Grace. “I think sexuality certainly plays a role in there. I’m a lot more attracted to men than I am to women. But to get to the heart of that question you have to consider … all my painting, really, to be a type of self-portraiture.”

Four years ago, his notions of “self-portraiture” became markedly more gender fluid, inspired in part by Jennie Livington’s celebrated 1990 documentary about New York’s black gay ballroom scene of the 1980s, Paris Is Burning.

“Young gay men were battling each other,” Wiley remarks, “not by fighting but by taking on the poses of many of the women in Vogue magazine. Those positionings were about how grand you are. It was about creating this shell, about creating this mask of power, even though you may have been one of the poorest people in the neighborhood or one of the most powerless people in the neighborhood.”

Wiley embraced that drag sensibility in his 2012 series, An Economy of Grace, which focused exclusively on the female figure. Painting after painting resounds with opulent grandeur, whether Wiley is summoning a haughty ferocity from his sitter for Judith and Holofernes (his spin on Giovanni Baglione’s 1608 oil on canvas Judith and the Head of Holofernes) or a sassy allure in the poser for Portrait of Mary Hill, Lady Killigrew (after Anthony Van Dyck).

In the former, Wiley’s female model is crowned in a towering beehive hairdo and wears an elegant blue gown by Givenchy designer Riccardo Tisci. In the latter, his big-boned leotard-clad model sports tattoos, fishnet tights, a nose stud and a short-cropped Afro dyed blond, all preposterously echoing the aristocratic stance of her namesake portrait’s more fragile-looking subject. Wiley strikes a quieter, more enigmatic effect in Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (adapted from Sir Edwin Landseer’s 1839 painting of the same name), as his elegant model strolls away from the viewer into dense patterns of flora and foliage.

No matter how lavish and elaborate, Wiley’s paintings are driven by something raw that caught his eye in Harlem, Brooklyn, or the locales he has explored in Brazil, Haiti, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. His models may be as unfamiliar with Wiley’s art-history touchstones as Arbus’s subjects were of the photographic tradition. But their contributions to the painter’s work are incalculable. That pavement energy is what motivates him, as it did Arbus.

“It’s a matter of getting out into the streets,” he says, “and discovering it.”