The Virgins parade through the city. On Cusco sidewalks, in parks and plazas, their faces brush against businessmen, beggars, girls in plaid skirts with schoolbags slung over their shoulders. Someone may look up and see Our Lady of Cocharcas enthroned above the curb or ducking down a cobblestone alleyway, baroque wings flapping. Saint Rose of Lima may bump into a woman carrying groceries as the streetlight changes.

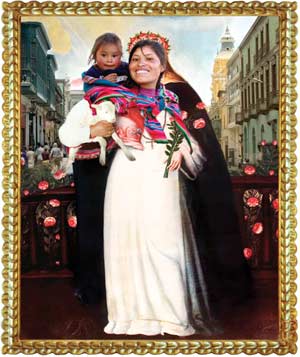

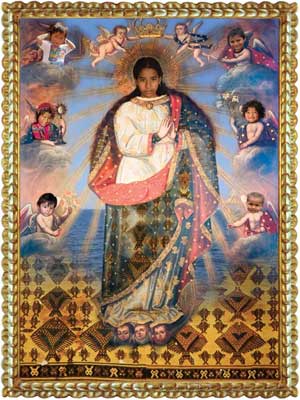

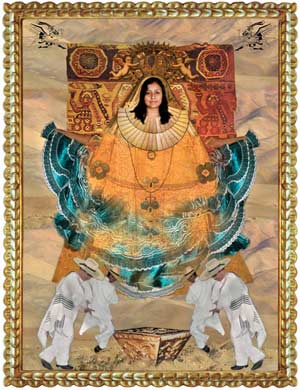

Spanish colonial art is famous for its Virgins. Peruvian-born artist Ana de Orbegoso wanted to create a series of images that would both pay tribute to and critique that tradition. She appropriated Spanish images of the saints and Virgins, and then used modern photographic techniques to replace the docile, European faces with the faces of the Peruvian women of today. Her giclée prints superimpose the new over the old, the empowered over the objectified, drawing attention to both.

But, instead of confining the works in art galleries, de Orbegoso wanted to make the Virgins a part of the modern landscape—Urban Virgins. She turned copies of each collage into a costume for her accomplices to wear on a walking tour of Cusco. Picture an unlucky employee lumbering between sandwich boards, and you’ll have some idea of the scene, but instead of advertisements they’re walking works of art.

By this juxtaposition of colonial imagery with city environments, de Orbegoso hoped to show that these icons were never part of the world they inhabited. Instead, they embodied, and were used to impose, European values and standards on the conquered Americas. According to de Orbegoso, the colonial Virgin was propaganda, promoting “the ideals to which native women were supposed to strive—purity, benevolence, and compliance.” Like the Holy Mother, they should be blank, silent, and, preferably, as white as possible.

Imperial conquest is more than physical subjugation; it colonizes bodies, minds, and—most dangerously—imaginations. Along with muskets and disease, the Spanish brought their language, their religion, and their culture. Colonized artists, de Orbegoso says, were forced to reject their native art forms in order to mimic the Spanish style. Express yourself, if you must, the Spanish said, but our way, not yours. In Urban Virgins, de Orbegoso rejects the oppressive legacy of colonial vision by replacing the anonymous saints with photographs of living women. In place of the ideal, she offers the real—a new kind of icon.

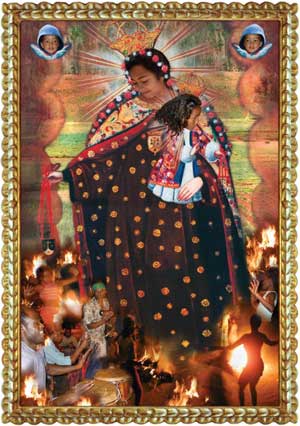

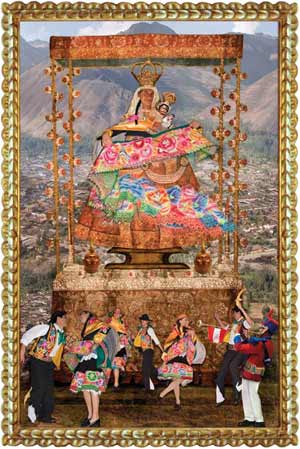

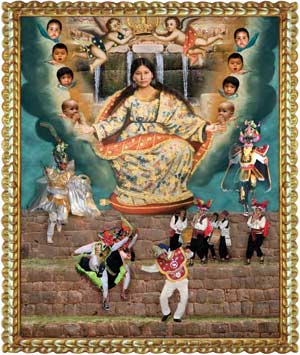

While the colonial Virgin was a static representation of a complex reality, de Orbegoso’s Virgins embody the intricacies of South America, of Peru, of Cusco, which she calls a “fusion of European and indigenous cultures . . . where colonial structures superimpose Inca walls, and Christian beliefs coexist with Andean spirituality.” The Virgins are surrounded by trappings of the old and new, symbols of prosperity, poverty, celebration, and tragedy. At their feet: flames and flowers, dancers, begging children, escaped slaves.

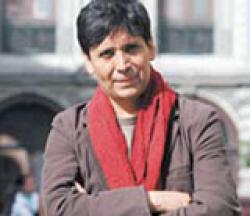

In the suite presented here, de Orbegoso’s prints are paired with persona poems by Odi Gonzales. Gonzales was born and raised in Cusco; before he met de Orbegoso, he had published a book of poems, La escuela de Cusco (The Cusco School), in the personae of the anonymous Indian painters who worked depicting Christian saints, Virgins, and archangels in Peru’s highland monasteries in the seventeenth century. They were introduced by a mutual friend, and Ana asked if Odi would consider writing a poem to each of her images. “When I saw the first collages,” Gonzales says, “I was truly astonished. Ana’s work was so stimulating that I just started writing.”

And, appropriately, he began writing in Quechua (the official language of the Inca Empire), which he had grown up speaking. [Editor’s note: the poems are presented below in their original Quechua, as well as translated into English and Spanish.] “Like Ana, I am trying to make an intercultural statement by mixing languages, mixing cultures,” says Gonzales. “Quechua is an ancient oral language, in which you have to translate ideas, concepts from this culture into another. That is hard, but I always have the ancient heritage of my Quechua culture with me. I feel in Quechua.” The resulting poems both explicate and interpret the images, adding extra layers to each collage. The once-anonymous Virgins tell their own stories; they take back from colonial art the power to represent, interpret, and prophesy. Saint Rose of Lima, the first saint born to the Americas, announces, “I am Rosa. Florist of Five Corners. Gate of Flowers . . . Cusco will flower.”

In Gonzales’s poems, the Virgins embrace their role in the modern world in opposition to an idealistic Heaven. Here, Rosa says, is “an intricate tapestry of landscapes.” The Virgin of the North, her arms spread in blessing, says she does not need “the vaulted niche in the choral balcony of a cathedral . . . the naves of the old haven of a parochial temple / My altar—like a Bedouin tent—stands up in the desert / My watery kingdom sprouts in the meadows of sandy rivers.”

These are democratized Virgins. Occasionally, they lament the loss of some ornate enchantment they might have had as impervious ideals. The Immaculate Virgin, left like an ordinary woman “at the corner of Procuradores and Comercio streets,” asks “where are my believers, the followers of my sacred tours?” She is stranded on the curb: “Cusco. Plaza de Armas, 2 a.m. / Heavy trucks go back and forth.”

The Virgin of Mercy justifies this shift from the ideal to the real. The art of the colonial era offered the Americas “fat little angels carrying banners” and meek white women—art that was lying to itself and its audience. The collaboration of de Orbegoso and Gonzales, by contrast, honors the genuine flesh-and-blood women of Peru. It recognizes the real “little martyrs of Almudena temple,” the “street-working children,” the empowered and the needy. Colonial art celebrated “seraphim playing lute[,] . . . misty distances” instead of meaning, but these Virgins offer a better kind of Mercy—the love of what exists, the worship of what we are—art in action, women in the world.

—Honor Jones

My firm flesh, profane. Young and supple, abundant half-breed

bringing health to the poor

I am not Magdalena, Hemorroisa, the Samaritan,

the Adulteress

I am not the Moreneta, the virgin blackened by the fume of the candles

of the wild believers

I am Rosa. Florist of Five Corners. Gate of flowers.

Quinoa patch. Unwed provincial mother. I say:

Lima will perish, Cusco will flower

My cape waves. My cape fits my young mare waist. In my fingers the ring,

the palm of martyrdom

In my back-cradle my baby is not the Child-Virgin weaving

Not the Child of the Thorns. Or is it?

Is it Satuco, Santusa, Julico, a portrait of his father

that kicks and cries: a nipple

Mis carnaciones firmes, profanas. Carnaciones de terneja, de mestiza abundosa,

gorda como para pobre

No soy la Magdalena, la Hemorroisa, la Samaritana

la Adúltera

No soy la Moreneta, la virgen renegrida por el humo de las velas

de los feligreses contumaces

Yo soy Rosa. Florista de 5 esquinas. Portal de flores

Campo de quinua. Madre soltera provinciana. Digo:

Lima perecerá, Cusco florecerá

Mi túnica flamea. Mi túnica ciñe mi alzada de potranca. En mis dedos la sortija,

la palma del martirio

En mi espalda-cuna mi wawa no es la Virgen-niña hilando

No el Niño de la Espina. ¿O sí?.

Es el Satuco, la Santusa, el Julico retrato de su padre

que patea y clama: teta.

Aychaykunapas p’utiy p’utiy. Sipas wachachaq aychan hina,

wira wira waqchapaq hina

Manan Magdalenachu kani, Emorroisapas

manataqmi Samaritanapas, icha Pantaq Warmipas. Manan chay

velak yanayasqan Moreneta mamachachu kani. Rosan noqaqa kani.

Pisqa k’uchupi t’ika qhatuyoq. T’ika qhata. Kinua pampa. Wawasapa

mana qhariyoq llaqtamasin kani. Hinatan nini:

Liman ñak’arinqa, Qosqon t’ikarinqa

Kusmay phalalayan. Kusmaymi uywa sayayniyta mat’ipayan. Makiypi

sortihay, muchuy chonta ima.

Wasay q’epinapi wawachay

manan puskaq warma qollanachu. Manataqmi kiska chakichayuq erqey

uchuy taytachachu ¿Hinachu manachu?

Satukuchan payqa, Santusachan, taytan uya

Julikuchan payqa, waqaych’uru, ñuñu puchu erqe

Today, Tuesday the first. Day of San Gerardo, patron saint of tailors

and dressmakers

Moving festival of Maria Santisima of Transit

there are no ukukus, qhapaq qollas, teralas, saqras, or scissor

dancers

No troupes for the Pillpinto nation

Today cimarron fugitives dance for me. Stamping in the sacred salt flats

an intricate tapestry of landscapes

My embroidered shawl of flowers,

the anonymous artisan of Pampachiri?

The crown of roses and the pair of sweet cherubs

are the adornments for the fiesta

of my daughter’s birthday

Hoy, martes a primero. Día de San Gerardo, patrono de los sastres y

costureras

Fiesta móvil de María Santísima del Tránsito

no hay ukukus, qhapaq qollas, teralas, saqras ni danzantes

de tijeras

No cuadrillas de la nación Pillpinto

Hoy me danzan cimarrones. Angeles prietos

en arrobamiento místico. Zapateo en el salar votivo

una complicada composición de fondos

Mi manto de tupido brocateado

¿el anónimo de Pampachiri?

La corona de rosas y la pareja de amorcillos

son las galas por la fiesta

de cumpleaños de mi hija

Killa qallariy martes p’unchay, San Herardoq sumaq p‘unchaynin

tukuy siraqkunaq Paypa marq’asqan. Kunan p’unchay

Qollanan Marya Santisima del Transito muyuq raymin

mana ukukullapas kanchu, qhapaq qollapas, teralapas, saqrakunapas

manataqmi tihiras tusuqkunapas kanllataqchu

mana Pillpintu suyumanta dansaqkunapas

Kunanqa tusupaywan yananiraq runakunan. Ch’illu k’illki

sumaq tusuqkuna, muspha muspha t’aqyatayaqkuna

kachipanpa laqhayasqa karu allpakuna qhepaypi

Sumaq t’ikallisqa p’istunay

¿Panpachirimantachu kanman icha?

Imarayku t’ika pilluy, chay sumaqyasqa k’illkichakunapas kaypi?

imaraykus kaypi kanku?

wawachaypa wata fistachan raykulla kanku

My skirt goes around eight times. Region: Yunga-Altiplano

My Castilian center skirt, embroidered by the linen weavers of Lucre

honoring my attire

My hair is the braid of a young woman from Langui

The town in the background could be Pisac as seen from the Taray over-view

the Callejon de Huaylas from the Cuesta de Animas. Switchbacks.

on this hill the Virgin’s bearers gave up

“Take me to the chapel of the Hospital of the Natives,” I said

but they left me here like a Tired Boulder

Mondays—the cattle fair—venders visit me

Mi pollera tiene 8 vueltas. Región: Yunga-Altiplano

Mi fondo, mi centro de castilla bordado por los tocuyeros de Lucre

honra mi vestuario

Mi cabellera son las trenzas de una muchacha de Langui

La población que se ve al fondo puede ser Pisac desde el mirador de Taray

el Callejón de Huaylas desde la Cuesta de las Animas. Cimbral.

en esta colina desistió la cuadrilla de cargadores de la Virgen

“Llévenme a la capilla del Hospital de Naturales” dije

y aquí me dejaron como a la Piedra Cansada

Los lunes—feria del ganado—me visitan los minoristas

Yunka qolla suyukunamanta pusaq muyuq phalikawan p’achakuni

Ukhu phalikay, kastilla phalikay, tukuy p’achay

Lukre siray kamayoq sirasqan

Chukchaytaqmi Langui wachachaq sinp’an

Qhepaypi karu wasikuna paqta kanman P’isaq llaqta, Taraymanta qhawalayasqa

otaq Waylas K’ikllu kanman Nuna Wayq’omanta rikukuq. Q’enqo

Kay qhata patapin lluy Mamacha q’epeqkuna samapusqaku

“Onqoqkunaq hanpi wasi kapillanman apawaychis” nirqani

paykuna ichaqa saqeywanku kay qhatapi, Rumi Sayk’usqata hina

Uywa qhatu p’unchaypi ichaqa pisi t’aqayoq runa watukamanku

My morning shower at the gate of the red birds

The mouthwash

The diligent cleaning of the intimate parts

—immersion in the Tambomachay springs—

are my ceremonies of eternal cleansing:

at age ten

I was taken forcefully at the urinal of the princess

Calf of the thermal springs

Little children sick with fear swirl around me

they look for my maternal breast

the smell of milk?

At the gate of thunder

appear those who

call back the scared spirits

Mi baño matinal en el andén de las aves coloradas

El enjuague bucal

El aseo diligente de la parte de las vergüenzas

—sumersión en los puquios de Tambomachay—

son mis ceremonias de lavado, de ablución perpetua:

a los 10

fui forzada en el mingitorio de las princesas

Terneja de las aguas termales

Parvulitos con mal de susto me asedian

me buscan el seno materno

¿olor a leche?

En la terraza de los truenos

cunden los llamadores de ánimo

Pillkupata raqaypi tutamanta armayniy

simi moqch’ikuyniy

pkakay ukhu sumaq ununayniy ima

—Tanpumach’ay pukyupi challpuykuy—

noqapaq kan ch’uyayckakuy, mana tukukuq mayllina saminchakuy:

chunka watachaypi

ñust’a hisp’ana uraypi kunpawanku

Pukyu unu wachacha

mancharisqa erqekuna qatipayawanku

k’iki ñuñuyta masqhaspa taripawanku

¿ñukñu q’apay?

Q’aqya pata k’ikllukunapi

manchali nuna waqyapakuqkuna waqyaykachanku

Cattle brander, tamer, salt dealer

butcher, pork castrator, bird breeder

hidden-treasure hunter, food seller

these are the jobs in God’s kingdom

For us

the sea is our field

Weaned with cetacean bile, my little brothers,

a prodigious family, and I

the firstborn daughter

wait the return of my father the fisherman

who went to sea

three days ago

Marcador de ganados, amansador, rescatista de sal,

matancero, capador de cerdos, pajarero,

buscador de tapados, vivandera. . .

son los oficios en el reino de Dios

Para nosotros

el mar es nuestra chacra

Destetados con hiel de cetáceo, mis hermanitos

familia numerosa, y yo

la primogénita

aguardamos el retorno de mi padre pescador

que se hizo a la mar

hace tres días

Uywa tuyruq, uywa atipaq, kachi qhatuq

ñak’aq, khuchi kapador, pichinku mirachiq

qori maskhapakuq, chupi qhatu…

chayllan kay Taytanchispa suyunkunapi tukuy llank’ay

Noqaykupaq ichaqa

chakraykun hatun qocha

Challwakunaq hayaqenwan hanuk’asqa

turachaykuna, khullu khullulla, noqawan ima

phiwi ususi

suyapakuyku kaypi challwaq taytay kutimunanta

kinsa p’unchayña haykun lamarqochaman

manaraq kutimunchu

Although I am not from the highlands

fissures, corners, watersheds, ravines

I have the pride, the erect neck

of the llama herds, first ladies

ladies crossing crevices and depressions

I do not have the vaulted niche in the choral balcony of a cathedral

in the naves of the old haven of a parochial temple

My altar—like a Bedouin tent—stands up

in the desert

My watery kingdom sprouts in the meadows of sandy rivers

The subtle bow of my father—northern rider—

upholds the heritage of the northern kingdoms:

my blood

Aunque no soy de las cuestas y laderas de la serranía

abras, rinconadas, cuencas, quebradas

tengo la altivez, el cuello erguido

de las tropillas de llamas primeras damas

ladies pasando las angosturas y hoyadas

No tengo hornacina en la capilla del trascoro de una catedral

en las naves de la bóveda vaída de un templo parroquial

Mi altar—como la tienda de los beduinos—se alza

en el desierto

En los remansos de los ríos de arena brota mi reino acuoso

La sutil venia de mi padre –un chalán-

guarda la estirpe de los señoríos del norte:

mi sangre

Maski wayq’okunapi, urin qhatakunapi mana paqarinay kaqtinpas

willk’ikunapi, k’ikllu k’uchukunapi, lluy p’ukru ukhukunapi

mana tiyaqtiypas, ichaqa noqa

sayaq kunka apusonqo kani

suri llamakuna hina, sumaq sipaskuna

k’ikllukuna chinpaykachaq sumaq ñust’akuna

Manan apu sunturniy kanchu takiq kapilla qhepapipas

manataqmi manqos raqay wasi qatapipas

Antharay—purun panpa runaq ch’ukllan hina—kan

altarniy sayarin aqo qhatapi

P‘onqo aqomayukunapi phutun unuchasqa suyuy

Chalan taytaypa sumaq k’umuyayninmi kan

chincha suyu hatun runakunaq apulayan:

paykunan yawarniy kanku

Golden dalmatic, my tight clothing

reveals the body that it covers,

designer of the Florentine school?

The burning cinnamon color of my face

was plastered with weasel bile,

the master of Pitumarca?

The troupe of children,

fat little angels carrying banners?

seraphims playing lute, trumpet-playing angels?

not misty distances alone

The little martyrs of Almudena temple

street-working children

Clothing of angular folds, flying capes

cave ornamentation

Paracas shawl?

The author’s signature is a bird hidden

in the layers of varnish

Dalmática dorada, mi ajustada prenda

trasciende la anatomía que cubre

¿escuela florentina?

El encendido encarne de mi tez canela

fue enlucido con hiel de comadreja

¿el maestro de Pitumarca?

La cuadrilla de infantes

¿gordos angelillos desnudos portando cartelas?

¿serafines tocando laúdes, ángeles trompeteros?

no lejanías brumosas

Los pequeños mártires del templo de la Almudena

niños-trabajadores de la calle

Vestimenta de pliegues quebrados, capa volante

ornamentación de grutescos

¿manto Paracas?

La firma del autor es un gorrión varado

en las capas de barnices

Kay t’eqe p’achay, qorinchasqa phulluy

sumaq ukhuykunata riqhurichin

¿Florentina yachay wasimantachu kanman icha?

Uyay aychapas pukay panty yawrarishian

maskipas unkakaq hayaqenwan llusisqa

¿Pitumarkamanta llunch’iqchu kanman icha?

¿Kay tawqa chikuchakunari?

t’ika hap’ilayaq k’illki oqochukunachu kankuman

¿waqra phukuq serafinkunachu, arpa maywiqkunachu?

mana karunchasqa phuyupas kanchu

Almudena kapilla muchuy waqcha warmachakunan kanku

hawapi llank’aq erqechakuna

Taparasqa sumaq p’achay, phalalayaq llaqollay

tukuypas phallchakunawan t’ikallisqa

¿Paraqas p’istunachu kanman icha?

Llinp’iqpa sutinpi sayan huk pichitanka

llinphi ukhupi chinkasqa

I am not a scarecrow of the wheat fields, nor of my flowering potato patches

a Caracoto troupe dancer?

Since the death of my husband, of my beheaded children

slaughtered like sheep / massacre of the innocent saints

I became the head of the resistance

in the war zone

I fight against murderers from both sides

Chariots of fire fly around me. My decimated battalions

boil in my head. Wandering souls

My march ends in humble cemeteries

tombs where I buried my dead. It is there I weep

and clean my musket

No soy espantapájaros de los trigales, de mis papales en flor

¿danzante de las pandillas de Caracoto?

A la muerte de mi marido, de mis hijos degollados

como carneros / matanza de los santos inocentes

me hice cabecilla del grupo de ronderas

de la zona de emergencia

Lucho contra los matarifes de ambos bandos

Carruajes de fuego me sobrevuelan. Mis batallones diezmados

bullen en mi cabeza. Almas en pena

Mi marcha termina en humildes camposantos

fosas donde enterré a mis muertos. Allí sollozo

y limpio mi arcabuz

Manan t’ikariq papa ukhupi chakra manchachichu kani

¿Karaqotomanta tusuq q’achurichu kayman icha?

Qosay wañuqtin, chita hina ñak’asqa

llapan wawaykuna tukukuqtin / mana huchayoq sipinakuy

pusaq awqa madrina tukupuni, tukuy rikuq

manchay manchay suyukunapi

Tukuy ñak’aqkunapaqmi phiña kani, llapanwan tupani

Nina wantunakuna phalalayawan. Ñak’arisqa wallaykuna

umayman muyumun. Llaki nunakuna

Sapa p’unchay puriyniy ayapanpakunapi tukukun

ayaykunata panpaspa p’ukru ukhukunapi

Chaypin waqapakuni, walqanqayta allinchani

Cusco. Plaza de Armas, 2 a.m.

Heavy trucks go back and forth in my memory. Via Crucis.

Where are my believers, the followers of my sacred tours

at midnight? Where are the backpackers and the VIP tourists?

Brichera, Andean lover. Sensual rider in praying posture

Klaus

that huge Aryan banner no longer waves inside me

And what of the Nordic Brotherhood

of the Holy Drinkers of Plaza Regocijo?

And the Yauri herders? And the Quiquijana potters?

And the United Union of Silversmiths and the Guilders of San Blas? Who knows?

They have put me here, on my platform,

at the corner of Procuradores and Comercio streets. Not even

the fanatic widows who call me the Beauty of the Cathedral ask for me.

My faithful followers, my parade is gone. Are they false witnesses, taking refuge

at the Ukukus bar? Do they drink double inka shots in the Kamikaze?

Do they start flying at Mile Zero, in the whorehouse of Santutis?

The kids at my feet offer punch and cigarettes

Cusco. Plaza de Armas, 2.a.m.

Pesados camiones zigzagean en mi memoria. Vía Crucis.

¿Dónde están mis fieles, mis seguidores en mis recorridos procesionales

de medianoche? ¿Dónde mochileros y turistas VIP?

Brichera, andean lover. Jinetera en actitud orante

Klaus

ese enorme pendón ario ya no flamea dentro de mí

¿Y la Hermandad nórdica

de los Santos Bebedores de la Plaza Regocijo?

¿Y los troperos de Yauri? ¿Los olleros de Quiquijana?

¿Y el Gremio Conjunto de Plateros y Doradores de San Blas? Nonada

Me han plantado aquí, en mis andas,

en la esquina de Procuradores y Portal Comercio. Ni siquiera

claman por mí las beatorras que me llaman La Linda de la Catedral

Mis fieles, mi comparsa ida. ¿Perjuran acantonados

en la barra del Ukukus pub bar? Beben Inka’s shoot doble en el Kamikase

Alzan vuelo en Kilometro Cero, en Santutis?

Los párvulos a mis pies, ofrecen ponche y cigarrillos

Waqaypata Qosqo llaqta. Pacha illariy.

Llasan llasan kamiyunkuna umayman muyumun. Muchuy ñan.

¿Maytaq lluy qatichupaykunari? ¿Maypin kuskatuta layma puriqmasiykuna?

¿Maypitaq chay p’aqoyusqa wasa q’epikunari? ¿Maypi qolqeyoq puriqkuna?

Panpa warmi. Pantaq sipas. Qonqorchaki wachoq qoya

Klaws

chay hatun ario unancha manaña phalalayanchu ukhuykunapi. ¿Maypitaq

kunanri, chay Kusipatapi sumaq nordiko wayqepura ukyaqkuna? ¿Maypi

Yawri maqt’akuna? ¿May Kikihana manka llut’aqkuna?

¿Chay Sanblasmanta qori, qolqe takay kamayoqkuna, maypin? Yanqa.

Kaypin saqeywanku, kikin wantunay patapi

Prokuradores, Portal Komersio k’ikllupi. Manan tapuykunkuchu noqamanta

ch’ayña payallapas, chay qhasqo taka Munay uya Mamacha sutiyaqniykunapas

Qatipayaqniy qharikuna, orqo uywaykuna ripunku. Ichapas

ñakaywashanku Ukukus ch’akipana wasipi? Icha Kamikasepichu

hayt’apakuq Inka aqhata upiyashanku?

Ichachu musphayashanku Kilometro Seropi, Santutispi?

Chakiy patapi chikuchakuna poncheta, sayrita qhatukunku