In 1956, just two years after Brown v. Board of Education, Robert Penn Warren set off on a journey south to explore the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision. The slim volume he produced, Segregation: The Inner Conflict in the South, offered insight into the people caught in what the Saturday Review later termed “a storm they can neither conquer nor fully comprehend.” Now, a half century later, the Gulf South struggles in the wake of another storm, Hurricane Katrina, and faces a rebuilding effort not unlike the effort to rebuild the culture of the South after the legal walls of segregation had been struck down. The plight of the people, post-Katrina, is still mediated not only by class but also by color, the future is uncertain, and the ongoing identity of the Gulf South will be determined not only by how it will be rebuilt but also by how its past will be remembered. The region stands as a test for the whole nation. Are we hopelessly divided? Or can we still bridge The Gulf?

Where you come from is gone,

where you thought you were going to never was there,

and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.

—Flannery O’Connor

One: Present

Nearing my hometown, I turn west onto Interstate 10, the southernmost coast-to-coast highway in the US. I’ve driven this road thousands of times, and I know each curve and rise of it through the northern sections of Biloxi and Gulfport—a course roughly parallel to US Route 90, the beach road, also known as the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway. It’s five o’clock when I cross into Mississippi and it seems that the sky darkens almost instantly. In minutes it’s raining—the vestiges of a storm (Humberto) out in the gulf—and I can barely see the lights of a few cars out ahead of me. Some are pulled over, parked beneath the overpass, hazard lights flashing. People have learned to be wary of storms.

“It’s different now,” my brother, Joe, says at dinner. “Before Katrina there were so many older people telling stories of having ridden out Camille that nobody worried too much. That was the biggest storm to hit around here.” Then he recalls the other storm warning, a little while before Katrina hit, and how it turned out to be what he called “a false alarm.” “People prepared with supplies,” Joe tells me. “There were long lines at the grocery store and the gas station, but then nothing happened.” My grandmother, emboldened by the “false alarm” and her house’s having withstood Camille thirty-six years before, was among those who wanted to “ride out the storm” from home. “You remember,” Joe says. “You had to talk her into letting me take her to a shelter.”

When I ask my grandmother what she remembers, she conflates the two storms. Ninety-one, a woman who has spent most of her life in the same place, she knows she lives in Atlanta, where I do, because she had to evacuate after Katrina, but she thinks she was at home during landfall, not lying on a cot in a classroom at the public school near her house. Examined by a doctor after evacuating Gulfport, she was disoriented. She hadn’t eaten well for weeks, even though the shelter provided MREs, even though my brother had been able to drive to Mobile for food. The doctor spoke of trauma and depression, prescribed medication.

In her room at the nursing home in Atlanta, she recalls to me how very young I was when Camille hit, and how my parents moved my crib from room to room all night trying to avoid the water pouring in through the roof. When I try to remind her of Katrina—the cause of her displacement—she looks at me and her eyes turn glassy with confusion, her lips press tightly, her brow furrows deeply as she tries to piece together the events of the previous two years of her life. She has layered upon the old story of Camille the new story of Katrina. Between the two, there is the suggestion of both a narrative and a meta-narrative—the way she both remembers and forgets, the erasures, and how intricately intertwined memory and forgetting always are.

Mine, too, is a story about a story—how the storm will be inscribed on the physical landscape as well as on the landscape of our cultural memory. I wonder at the competing histories: what will be remembered, what forgotten? What dominant narrative is emerging? Watching the news, my grandmother turns to me when she sees Senator Trent Lott on the screen. “I made draperies for his house,” she says, aware I think, that theirs is a story intertwined by history: his house gone along with the work of her hands.

I spend the first night catching up with Joe. Because his house and our grandmother’s house are still in disrepair, he’s living with his girlfriend while working on the properties himself. I’ve booked a room at one of the casino hotels on the coast, and we sit in the bar for hours watching the Thursday night crowd on the gaming floor. Fifteen years ago, onshore gambling wasn’t permitted. Most casinos then were barges, moored against the beach in the shallow water. After Katrina, my brother tells me, the casinos “couldn’t get insurance offshore.” The need to get the economy of the coast rebuilt quickly made the state of Mississippi open the door for the construction of casinos on the shore. Now and again you’ll still hear some folks talking about “working on the boat” or “going down to the boat.”

In 1992, when legislation first approved “dockside” gambling, most Gulf Coast residents were ambivalent about the burgeoning industry. Not my brother. He was nineteen then—bored, restless, and hoping for a life in a town with more opportunity, more excitement. The casinos brought much of that—steady work in construction, good pay, often un-taxed, “under the table” he told me back then. In downtown Gulfport a new bar had opened—the E.O. Club, which stood for “Early Out,” and catered to the casino workers getting off their shifts. It was a dark, urban-looking space with a shiny wooden bar and a bandstand for the blues, bluegrass, and cover bands that played there weekly. My brother—good-looking, sweet, and effortlessly charming—was a regular there. He could talk to anyone, and he made contacts and found work for himself this way.

It wasn’t long before the casinos made a significant contribution to the economy. By 1996, monthly gaming revenues had increased from $10 million to $153 million. Before they opened, the unemployment rate in Mississippi was among the highest in the nation, so there was newfound hope in jobs with health insurance and other benefits and at the possibility of some revenues going to build communities and improve local schools. But people feared an erosion of the coast’s cultural heritage, the depletion of the wetlands, and the consequences of prosperity founded on the vice industry. I watched as title pawn businesses sprang up in the shadows of the newly opened casinos. It was a short walk from the Copa or the Grand in Gulfport to a squat, yellow bunker of a building where you could turn over the title to your car in exchange for a high-interest loan. Often I’d see the same cars parked there for over a month, and I knew that the owners had missed their pawn deadlines and couldn’t “buy” the vehicles back, and that the cars would be sold to someone else.

The security guard at my hotel is a friendly white woman in her sixties. She’s been here for ten years and feels grateful for the job. “Last ones out, first ones in,” she says proudly of the hotel workers before and after the storm. “Lost everything but my job, and when we came back to work, there was hot food from the Salvation Army.” In her voice is a mixture of what seems like appreciation for what she has and a good measure of contempt for the kind of rebuilding taking place. “The casino business is better than ever,” she says, “but the people need to have what they used to have. They won’t rebuild any gas stations along the beach, just condos we can’t afford, and only the casinos can have restaurants. What are the working people supposed to do?”

After the hurricane, her rent increased—despite the terms of her lease, she tells me, despite lost pay and no raise for returning—from $500 a month to $800. When I ask her about assistance from the government she wags her head fiercely: “Nobody has seen all the money. It’s been two years and we are still suffering. They said they wouldn’t price-gouge, but they are doing it.” Indeed, programs dedicated to helping the poor have benefited from only about 10 percent of the federal money, though the state was required by Congress to spend half of its billions to help low-income citizens trying to recover from the storm.

I ask her what she remembers of the storm itself, and her face softens. “It was like a bomb had went off. And now everywhere is slabs, just slabs. And the water is still full of debris—houses, cars. We need to dredge the gulf to get it all back, including the bodies,” she says. “Including the bodies.”

It’s nearly midnight and her shift is ending. Beyond the poolside deck where I have been talking to her, the gulf is flat and black. The lights of the Beau Rivage, reflected on the water, are all I can see.

Compared to the flurry of activity in the casino, downtown Gulfport seems abandoned, empty but for the few new businesses that have opened and the old ones that have reopened: the bank, a restaurant, pub, coffee shop, and Triplett-Day Drugs, which has been there as long as I can remember. At the rusted shell of the former public library a lone light fixture hangs above what was the entry to the stacks. A stairway spirals up to the sagging roof. Vacant lots broadcast one message—AVAILABLE—on sign after sign. Everywhere there are houses still bearing the markings of the officials who checked each dwelling for victims. It’s an odd hieroglyphics I learn to read—an X with symbols in each quadrant. My brother’s girlfriend, Aesha, tells me to look for the number at the bottom of the X; it shows how many dead were found.

The next morning, Aesha and I meet to talk at a new coffee shop where the young woman behind the counter is cheery and energetic—enthusiasm I take to be a good sign. As we sip tea I ask Aesha about this optimism, about where she thinks things stand on the coast. When the storm hit, she had been living in a lovely apartment above a law firm, just off Pass Road in Gulfport. She was a model tenant and worked, works still, as a legal secretary at another firm. Despite her considerable rent, she’d been saving to buy a house. She was fortunate that the building survived—albeit with damage—and that some of her things were safe. Aesha and her son sheltered at her parents’ house during landfall, but when she tried to return to her apartment, she was met with notice of her eviction. The owner’s daughter and her husband took the apartment because their home had been destroyed. Aesha, her belongings still inside the apartment, had to search for a storage unit—in New Orleans, ironically. Were it not for her parents, Aesha and her son would have been homeless, and her former landlords didn’t care—or couldn’t care—so busy were they dealing with their own difficult circumstances. Still, Aesha was among the lucky residents of the coast in many ways—her firm reopened quickly, and she had a place to live in the meantime. As she tells her story, I realize that she now marks time by the storms. Like the Gulf Coast Harrison County residents who refer to time before and after Camille as B.C. and A.C., Aesha recounts the events of her life in terms of their proximity to Katrina—“the day Katrina hit,” “two days after Katrina.”

I know she isn’t embellishing when she talks about how people interacted after the storm because I’ve heard these stories from my brother, too. “It was as if everyone banded together,” she says. “Everyone helped each other. People shared what they had, were even friendlier.” I want to remind her—but don’t—of being evicted. I know a preferred narrative is one of the common bonds between people in a time of crisis. This is often the way collective memory works, full of omissions, partial remembering, and purposeful forgetting. Gulf Coast residents are charged with rebuilding not just the physical structures and economy of the coast but also the memory of Katrina and its aftermath. In all revisions, words are important. Aesha still clenches her teeth when she remembers being called a “refugee.” “Evacuee,” she says. “I am an American—not a refugee in my own country.”

The idea of America is inscribed on the landscape of North Gulfport: streets named Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Florida, Arkansas, Alabama. My cousin Tammy lives just off Highway 49 on Alabama, at what used to be the intersection of Alabama and Jefferson, before Jefferson was blocked off and made a dead-end street. I always thought that change a great irony, as if the very ideals of President Jefferson were truncated as the people who lived on Jefferson became more cut off, more isolated. Even now, thirty years after the street was blocked, delivery trucks have trouble getting to the houses on Jefferson. Often ambulances and police cars drive right by.

Tammy has lived there with her children for nearly two decades—my great-uncle Son had willed his house to her. It stands beside the land that once held his famed Owl Club, on the eastern side of Highway 49, easily visible from my grandmother’s house on the western side. I park in front on the crushed-shell driveway. Tammy comes out to the porch when she hears my Yoo-hoo—the call we’ve been using all our lives, the call our parents and grandparents used whenever they came to this house.

The porch is stacked with moldy furniture that Tammy is intent on reclaiming. She’s been back in the house for a few months after having lived for over a year in a FEMA trailer on the property, while her home was being repaired. It’s a sturdy brick house, two bedrooms and one bath, on a lot with pecan, fig, and lime trees. It is one of the nicer homes on the street, evidence—along with run-down shotgun shacks and newer prefab homes—of the working class and working poor in this historically black neighborhood.

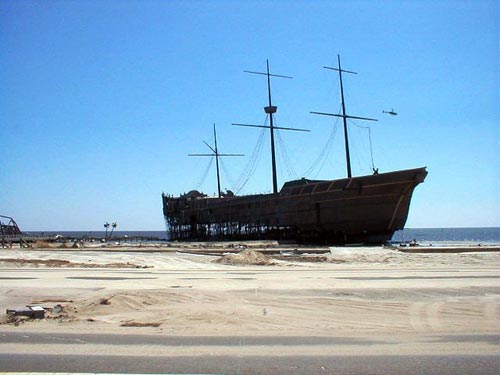

-

- Gulfport from the air, along highway 90. September 6, 2005. (Matt Ewalt / CC)

The state of Mississippi has spent $1.7 billion in federal funds on programs that, according to the New York Times, “have mostly benefited relatively affluent residents and big businesses.” Much of the money has been used to help utility and insurance companies as well as middle- and upper-income homeowners, whose houses are of greater value, instead of helping the poor, such as many of Tammy’s neighbors. “Donations and the work of a group from North Carolina are responsible for most people’s repairs in the area,” she says, surveying the streets. “If not for them, I couldn’t have completely fixed my house. I’d still be in that trailer.” Though state officials, including Governor Haley Barbour, insist that the state does not discriminate by race or income when giving aid to storm victims, many poor residents—including renters and those who couldn’t afford homeowner’s insurance—are ineligible for many aid programs. Some houses on Tammy’s street have been repaired, but many have not.

If the owners can’t afford to rebuild or repair a badly damaged house, the city demands that it be torn down. “But demolition is expensive,” she tells me. “They’ll come out and do it for you—tear down what’s left of your house and break up the slab and haul it away—but most people out here can’t afford what the city charges for demolition.” She points to an empty lot beside her house. “If you wait long enough, they’ll just tear it down anyway”—whether you want them to or not.

All along the coast, evidence of rebuilding—though sometimes terribly slow—marks the wild, devastated landscape. Until recently, debris littered the ground: crumbled buildings, great piles of concrete and rebar twisted into strange shapes, bridges headed nowhere. Concrete slabs so overtaken by grass, roots, and weeds it is as if no one ever lived there—so quickly has nature begun its rebuilding, its wild and green retaking of the land.

Just last year, schoolchildren in nearby Pass Christian attended class in trailers without running water and used portable toilets. Not until Good Morning America’s Robin Roberts—a native of the area—questioned FEMA director David Paulison about the delays did FEMA contract workers begin to dig the new well the school desperately needed. When I spoke to a member of the Mississippi House of Representatives from Pass Christian, she complained that the town still hadn’t seen the money they’d been promised.

Along the beach road and the highway, and in the neighborhoods farther inland, many still live in whole communities of FEMA trailers—nearly 10,000 trailers, many of them laden with formaldehyde. From a distance, they look like aboveground tombs of New Orleans’s famed cemeteries: white, orderly rows. Elsewhere, new condominium developments rise above the shoreline. Here and there a sign of what’s still to come: SOUTH BEACH and BEACHFRONT LIVING, ONLY BETTER.

Back at the casino for dinner, my brother, Aesha, and I sit outside on the patio, taking in the balmy evening air. I am telling them about a man I encountered at lunch—a casino “host” making his rounds to check on the patrons. The conversation with the man began as many of my conversations do in Gulfport—a quizzical look of semi-recognition, then the question, Where are you from? And then, Who are your people? Satisfied by my answers, he settled in to talk. A former educator and a former mayor of Gulfport, Bob Short’s predictions for the coast were grim. “Children here are going to have the same post-traumatic stress disorder as Vietnam vets. One child I know,” he said, “is afraid to take a bath now because he saw his mother washed out of the house by the storm.” Aesha clicks her tongue when I recount this, thinking, I am sure, about her son and Joe’s daughter, both clingy and nervous for a long time after the storm.

The young waiter serving our table has been listening off and on to my story, and he has his ideas, too, wants to share them—even gives me his card so I won’t forget his name. He’s from Louisiana, and he moved to the coast for work in the casino. “What’s different now is that the new generation respects the hurricanes, unlike the folks before. It needed to happen.” When I ask him what he means, he replies vaguely: “to teach us something” and “a cleansing, that’s what it was.” He turns to attend to another table, and I move on, wondering what he meant, wondering who needed to be cleansed. I’ve heard people opine about New Orleans and the people turned out by the storm: the poorer, working classes—overwhelmingly African American—all lumped together with supposed criminals that the city would rather not see return.

In the morning, the sky is clear and blue. As I drive along the beach highway I’m struck by how deceptively beautiful the water looks from a distance. The light makes it seem blue-green, though I know that it is a muddy brown and so shallow you have to walk out very far, nearly a mile, just to be in waist-deep. Debris from the storm still lurks beneath the surface. I’m still thinking about the idea of “cleansing” when I park in one of the bays and flip through the Fodor’s Gulf South. There is ominous foreshadowing in the book, published in late 2000: “Look on the positive side,” it instructs. “As long-time residents will remind you, obliging hurricanes will continue to obliterate the latest of mankind’s follies.” Those words seem not to anticipate a coast where only follies—hastily built condos and casinos—seem to be returning with any ease. I think of the waiter. I imagine it wasn’t the casinos he wanted to see washed away—but then, I don’t know what he meant.

A cleansing, he said. Erasure wrought by wind and water.

Looking west toward Pass Christian, toward Waveland, and Bay St. Louis—ground zero for the storm’s devastation—I consider the obvious metaphor. The nearly barren coastline: a slate wiped clean, or nearly clean. Then recovery, rebuilding, another version of the story.

Two: Past

Ships entering the harbor at Gulfport, the major crossroads of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, arrive at the intersection of the beach road, US 90, and US 49—the legendary highway of blues songs—by way of a deep channel that cuts through the brackish waters of the Mississippi Sound. Off the coast, a series of barrier islands—Cat, Horn, Petit Bois, Deer, Round, Ship, and some long-submerged sand keys—bracket the shoreline. I cleave to the window as the plane turns inland toward the airport in North Gulfport, trying to see what aerial photographs show—islands, like a row of uneven stitches, hemming the coast. Some of them are invisible from the shore; others loom up in a rise of pine trees against the horizon. Only the legendary Dog Key Island has completely disappeared.

All of the landscape is inscribed with the traces of things long gone. Everywhere the names of towns, rivers, shopping malls, and subdivisions bear witness to vanished Native American tribes, communities of former slaves, long-ago industrial districts, and transit routes. We call a neighborhood in Gulfport the Car Line because it was once the last stop for the streetcar, end of the line. Inland and across the railroad tracks is a community called The Quarters, so named, my grandmother tells me, for its black residents. There is irony in the signifying too; the Isle of Capri, near Point Cadet in Biloxi, was the first dockside casino to open its doors in 1992, and it bears a name similar to a pleasure resort and casino that operated just off the Mississippi coast in 1926—the Isle of Caprice, formerly Dog Key Island. We speak these names often, unaware of their history, forgetting how they came to be. Each generation is more distant from the real meanings of these names—the events and the people to which they refer. No longer talismans of memory, the words are monuments nonetheless, relics becoming more and more abstract.

Some names, however, bear lessons along with their forgotten history. The Isle of Caprice was once a popular destination for patrons of the sporting life as well as families out for a picnic. Visitors could sunbathe or swim, then listen to big-band orchestras, dance, dine, and gamble in a setting that was opulent with stuffed divans, thick carpets, and mahogany gaming tables. Aptly named, the resort was a place for whimsy and postwar revelry—a way for pleasure seekers to forget or move on from the past—and a boon for the coast’s tourism industry. Built on a sand shoal, the resort’s naming proved to be prophetic as well. After a few years, the waters began to overtake the key, never fully receding. By 1932, it was gone, completely submerged, Dog Key defeated by the capricious gulf waters.

In 1932 my grandmother Leretta, the second youngest of seven children born to Eugenia McGee Dixon and Will Dixon, was sixteen. Her parents had moved to Gulfport around the turn of the century, just two years after the deep-water port was constructed and the town was officially incorporated into the state of Mississippi. The first boundary stakes had been driven in 1887, but Gulfport got its second start when multimillionaire oilman, Captain Joseph T. Jones, bought the struggling Gulf and Ship Island Railroad and began dredging a deep channel from the island to the end of the car line.

The young Dixon couple must have imagined the great possibility of work for Will on the docks in a budding lumber-shipping industry, and work for Eugenia as a domestic in the mansions along the beach. The coast’s seafood industry, which had been established when the first canning plant opened in the late nineteenth century, didn’t employ blacks. Most of the workers were drawn from the influx of Yugoslavs and Slovenians to Biloxi in 1890, as well as Polish immigrants brought in from Baltimore and Acadians from Louisiana.

Will and Eugenia had left the cotton fields of the delta behind them, trading life along the Mississippi River for life on the Gulf Coast. They settled just outside the city limits, acquiring land from a man called Griswold, for whom the community was named. The area, now known as North Gulfport, has been—for as long as my grandmother can remember—a black section of town. It would be several years before the young couple’s troubles started, before Will Dixon would abandon the family, years before Leretta would wake in the middle of the night and see her mother fall back, dead, from the chamber pot on which she’d been sitting—influenza, most likely, which had made its way into port cities around the world. Between 1918 and 1919—and even into early 1920—the pandemic swept through the Mississippi Gulf Coast, leaving at least ten thousand people, on record, dead.

Gulfport grew a good deal during my grandmother’s childhood—the roads paved in 1908, the first hospital built in 1909, the library in 1917. After the death of their mother, the children made money from all sorts of jobs. One brother, Roscoe Dixon, worked at a slaughterhouse and brought home meat. The girls took in wash, cooked, and cleaned houses. All of them crabbed in the gulf and sold their catch to the white people whose homes fronted the coastline. Though segregated, the narrow, natural beach was open to blacks for the purpose of crossing over to the water to set crab traps, and to carry their harvest to the back stoops of those big houses.

Hubert Dixon, another of Leretta’s brothers, worked as a bellhop at the Great Southern Hotel. Captain Jones had built the 250-room hotel, which overlooked the water at the end of Twenty-fifth Avenue in Gulfport Harbor, in 1903. Leretta recalls in great detail the stories her brother told of working at the Great Southern—the excitement on the coast as visitors arrived, all the bustling to and from Union Station. Once, Al Capone came down to gamble and, upon arriving, shook Hubert’s hand.

Nineteen thirty-two brought an end to that, with Capone in prison and offshore gambling gone, for a while at least, from the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Much too late had the owner of the Isle of Caprice, Walter Henry Hunt, planned to build a protective seawall. The narrative of legalized offshore gambling had been written—then quickly erased by the gulf waters. As the tourism industry lagged, shipping and shipbuilding would bolster the coast’s economy—supplemented by fines for illegal, backroom gambling. It was in such an atmosphere of growth and possibility that Leretta’s oldest brother, Son Dixon, a budding entrepreneur, imagined building a nightclub. He would return from his World War II naval tour of duty with a plan.

The Owl Club stood on Alabama Avenue just outside the city limits in unincorporated North Gulfport. Son Dixon built the low-ceilinged barroom and dance hall next to his own house. A driveway and a garage, which held his wife’s pink Cadillac, separated the two structures. Business was good. Every day working men sidled up to the mahogany bar to smoke cigars and drink. The walls were lined with bottles of whiskey and Regal Quarts cans of beer. There was a jukebox in the corner playing records Son Dixon bought on his monthly trips to New Orleans. Leretta worked for her brother in the kitchen, frying chicken or fish, simmering pots of red beans. Before long, he’d made enough money to start buying property in Griswold Community, his birthplace. Stacks of quitclaim deeds in our family’s safe show Son Dixon’s acquisition of large corner lots on major thoroughfares in North Gulfport. The dates on the deeds, a calendar from Leretta’s beauty shop, an early EISENHOWER FOR PRESIDENT button—who knows why it was saved—hint at a story of 1950s Gulfport.

By that time, the protective seawall along the Mississippi coast had been built, the government had transformed Highway 90, the coast road, into America’s first four-lane superhighway, and plans were underway to create a sand beach twenty-six miles long, fronting the towns of Gulfport, Biloxi, Long Beach, D’Iberville, and Pass Christian. The sand beach was a way to boost tourism and the postwar economy of the coast, and the highway literally paved the way for more urban waterfront development.

The “longest man-made beach in the world” was completed in 1955. The restaurants and hotels alongside it, lit up by neon signs, were for whites only. In a photograph, my grandmother stands on the small part of the beach designated for “colored” people. It would not be until 1968, four years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, that the beaches were finally, fully integrated. My grandmother remembers going to the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s in downtown Gulfport that year, just a few blocks from the beach, and encountering an elderly white woman and her daughter. “When the woman saw me sit down at the counter,” my grandmother tells me, “she asked her daughter to take her somewhere else.” The daughter said, “Mama, they’re going to be everywhere.” “It used to be color,” my grandmother muses. “Then the only thing that could keep us out of those restaurants on the beach was money.”

Son Dixon made money building tiny shotgun houses and duplexes in North Gulfport, where the population had increased by 50 percent between 1940 and 1950. There were people who needed places to live, and Son Dixon’s properties—which as recently as the early 1990s rented for only $200 a month—were affordable. The inauguration of Mayor Milton T. Evans in 1949 marked the beginning of the biggest growth period in the history of Gulfport. Opportunities followed this growth, but so did environmental havoc.

Shore erosion is a natural occurrence on the Gulf Coast. With rising sea levels, water overtakes land and marshes disappear as nature revises the landscape. Evidence of the loss of wetlands in the United States has been documented since the turn of the twentieth century, and along the Mississippi Gulf Coast, significant changes have taken place since the 1950s. Between 1950 and 1992 developed land usage tripled, and nearly 40 percent of marsh loss can be attributed to replacement by developed land. Among the most valuable ecosystems on earth, wetlands are responsible for cleansing polluted water, recharging groundwater, and absorbing storm wave energy. In Gulfport and Biloxi, where dredge-and-fill commercial, industrial, and residential developments have been extensive, there have been especially high rates of marsh loss.

When Hurricane Camille hit in August 1969, the surge in coastal development, which began in 1950, had already reduced the wetlands. With less marshland to absorb storm wave energy, the winds that battered the coast reached 210 miles per hour and the storm surge reached over 25 feet above normal sea level. The beachfront was devastated. Though Son Dixon weathered the storm, along with many of the homes he owned, over 6,000 residential and commercial buildings were destroyed, and many more damaged. The local death count was 132.

Every hurricane season that I can remember began with news footage of Camille—always the replayed scenes of waves crashing against the shore, palm trees leaned far enough over to brush the sand with their fronds, images of destroyed houses and apartment buildings, a grave voice warning us to evacuate. On the beach in Gulfport, Camille washed a small tugboat ashore. Someone renamed it the USS Hurricane Camille and turned it into a souvenir shop—a reminder of the storm and a place to buy trinkets, the kitschy talismans of memory. It was still in the same place after Katrina—all around it destruction. Though the USS Hurricane Camille endures, the foundation of the Richelieu Apartments—where twenty-three people died during Camille—was bulldozed in 1995. For so long a reminder—a monument to the dead—the site is now a shopping center.

Between 1992—when dockside gambling became legal—and 1996, the number of hotel rooms on the coast increased from 6,000 to over 9,000. There was work in renovating existing hotels and in constructing new ones, and Joe quickly got a job demolishing and building walls at Treasure Bay—a casino moored in the marina—and installing carpet and wallpaper in the old Royal D’Iberville Hotel across the street. He was frequently called to jobs at hotels along the coast and in other cities, including New Orleans. He’d spend weeks living in whatever hotel he was working on, in whatever city. At night, he and the other men would visit the local bars—especially those in the French Quarter. Many of them worked in one casino and socialized next door in another. Joe was young, and this was an exciting life with good pay. He was a hard worker—efficient and likeable—and before long, the contractors were seeking him out, often to lead a crew. When construction began on the Beau Rivage, Joe was back on the coast, living in one of the houses he’d inherited years before. And he was steadily gaining experience working at construction sites, doing remodeling—carpet, wallpaper, paint, interior walls, and ceilings—gaining the kind of skills that he’d need if he was going to step into our uncle Son’s shoes as a landlord.

Of course, though, there were downsides. Joe and his co-workers, often recent immigrants from Mexico and unskilled laborers, received their pay in cash. Without any health insurance benefits, including workman’s compensation, every worker to sustain injuries on the job paid for the trip to the emergency room himself. Despite casino revenues that went to improve the Biloxi school system and police department, the industry brought a host of social ills. And the casinos accelerated the coast’s environmental degradation. Prior to Katrina, the Mississippi Department of Marine Resources documented direct and indirect detrimental impacts of dockside gaming on the coast, in the forms of dredging for barge placement, water bottom and wetland fill, shoreline alteration, water bottom shading, increased surface-water runoff in impervious areas, and degraded water quality easily visible in the pollutants washing into coastal waters. By 1998, dead fish and debris were a frequent sight along the beach.

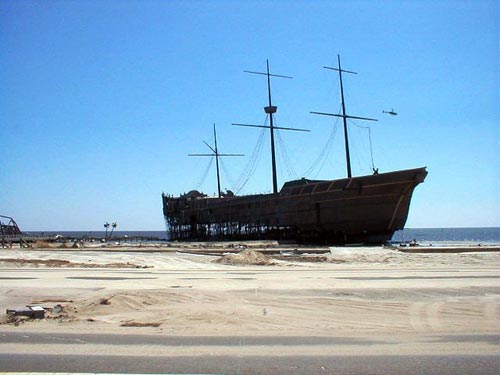

-

- The Treasure Bay casino boat, beached post-Katrina. (Shawn Zehnder Lea / CC)

In the year leading up to landfall, a few miles up Highway 49 from the beach, my brother was beginning work on the shotgun houses. The boost in tourism brought on by the casinos had created a greater need for housing. North Gulfport had finally been annexed, and the strip of 49 that ran right through it was undergoing a great deal of development. Where there had been darkness for so many years, streetlights appeared, guiding travelers from the beach to I‑10, past the Wal-Mart, fast food restaurants, motels, gas stations, and convenience stores, up to the new outlet mall. His property was right in the middle of this flurry of activity.

Ella Holmes Hinds, city councilwoman for the district, had long been fighting to keep the residential sections of the community intact while businesses wanted to acquire the land cheap and transform it into a commercial district. Everywhere there were FOR SALE signs signaling property rezoned for commercial use. For years, the shotgun houses Son Dixon built had languished in a state of disrepair—unpainted, sagging—many still occupied by tenants who’d been there since he was alive, the rest vacant, or occupied sporadically by drug users. The remaining tenants—Miss Mary in the duplex at the corner of MLK and Arkansas, Chapman’s fruit stand and A.D.’s bail-bond business at Old 49 and MLK—had paid the rent, now up to $250 a month, steadily for years and had begun to fear they’d lose their houses to development after all. When Joe finally decided to take over the family business and repair the old properties, my grandmother was thrilled, and so were the people in the neighborhood.

Joe put in new floors and carpeting, new countertops and appliances, brushed on a good coat of paint. Miss Mary nearly cried when Joe fixed up her house. Each day, whenever he was outside, someone would drive by, stop and roll the window down to look. “People kept coming by to say thank you,” he told me. And, “Man, I appreciate what you’re doing for the community.” For many longtime residents, it must have seemed as if Son Dixon had returned in the form of his young nephew. By the start of summer 2005, nearly all the houses were renovated and rented. In a few months, when enough checks came in, he could get them insured.

Katrina made landfall on August 29, 2005. Out in the gulf, Ship Island was completely submerged—the storm surge up to 27 feet. Mississippi officials recorded 238 deaths, and tens of thousands of people displaced. Though a renter, Miss Mary had lived in her duplex for nearly 30 years. In it she survived the storm, but before long she’d have to leave, because the severely damaged structure began to fall down around her. Hearing her story, I thought of Bessie Smith’s “Backwater Blues”: When it thunders and lightnin’ and the wind begins to blow, there’s thousands of people ain’t got no place to go. Joe couldn’t afford the large-scale repairs her house needed. Within two years, the city demolished the duplex, and my brother was struggling to pay taxes on vacant land.

In the weeks following the storm, Joe busied himself, like a lot of coast residents, aiding the efforts to get food and water to victims. He unloaded trucks, stacked boxes of supplies, handed out diapers and water bottles, clothing and canned goods to people lined up in the heat. He cleaned out his refrigerator filled with mold and spoiled food. He patched what he could of Miss Mary’s roof. He waited for rain when he needed to take a shower. He sat up in the hot, dark house with his grandmother, listening as she fell asleep; listening to the sirens of police cars passing by; listening for the sounds of anyone not inside for curfew; into the night, just listening.

He got a job directing traffic, standing on the highway waving a flag. He got a job removing debris, clearing the roadways, sorting through the remnants of life before Katrina. He stood in line for a check. He got a job cleaning the beach. He got a job as a watcher, scanning the white and glaring sand for debris that would clog the machines that cleaned the beach. He told me they were looking for chicken bones, scattered there from the warehouses, and the carcasses of animals. On a quarter-tank of gas, he drove to Mobile for supplies. He bought candles and flashlights, food and water, medicine for his grandmother, and beer. He drank with his friends. They drank and looked at the destruction and rubbed their heads and drank some more. He drank on the porch in the evenings by himself. He sat watching the trucks go by on Highway 49. He found a hill where his cell phone worked and called to say, “Everything is gone.”

Hegel wrote, “When we turn to survey the past, the first thing we see is nothing but ruins.” As I contemplate the development of the coast, looking at old photographs of once-new buildings—the pride of a growing city—I see beneath them the destruction wrought by Katrina. The story of the coast has been a story of urban development driven by economic factors, heedless of the environmental effects. It can be seen in all the concrete poured on the coast. It can be seen in the changing narrative since 1992, a historic landscape transformed into a neon vista—casinos, parking decks.

The past can only be understood in the context of the present, overlapped as they are, one informing the other. Surrounded by the present devastation, I did not expect to see what I did when I looked to the past. I was going back to read the nostalgic narrative I thought was there—that the gaming industry, responsible for so much recent land and economic development on the coast, was a new arrival, not something already ingrained in the culture of the place. I expected to find a story that would tell me everything had been fine up until 1992, not that development had been damaging the coast since as early as 1950.

As the plane lifts over North Gulfport, over Turkey Creek, turning to sweep out over the sound before heading north and east to Atlanta, I try to see all the places of my childhood that I am once again leaving, putting them, like the past, behind me—though the scrim of loss hangs before my mind’s eye. Bessie Smith’s lyrics come back to me again: I went and stood up on some high old lonesome hill, then looked down on the house where I used to live.

Three: Future

The morning after the storm, hundreds of live oaks still stood among the coastal rubble. They held in their branches a car, a boat, pages torn from books, furniture. Some people who had managed to climb out of windows clung to them for survival as the waters rose. These ancient trees, some as many as 500 years old, remain as monuments not only to the storm but also to something beyond Katrina—sentries standing guard, witnessing the history of the coast. Stripped of leaves, haggard, twisted and leaning, the trees suggest a narrative of survival and resilience. In the past two years, as the leaves have begun to return, the trees seem a monument to the very idea of recovery.

Man-made monuments tell a different story. Never neutral, they tend to represent the narratives and memories of those citizens with the political power and money to construct them. They inscribe a particular narrative onto the landscape while—often—subjugating or erasing other narratives, telling only part of the story. As I write, determined citizens in Gulfport are working to erect some kind of monument to the Louisiana Native Guard—the first officially sanctioned regiment of African American soldiers in the Union Army—on Ship Island, where they were stationed. “Of the hundreds of Civil War monuments North and South,” historian Eric Foner writes, “only a handful depict the 200,000 African-Americans who fought for the Union.” With such erasures commonplace, it is no wonder that citizens of the Gulf Coast are concerned with historical memory. And it is no wonder that the struggle for the national memory of New Orleans—given the government’s response in the days after the levees broke—is a contentious one. A woman waiting in line at a store with me worried that people were forgetting the victims on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, what they had endured and endure still. “There’s a difference between a natural disaster and the man-made disaster of New Orleans,” she said. “Don’t forget about us.”

The first monument erected on the coast to remember Katrina and its victims stands on the town green in Biloxi. Part of the memorial is a clear Plexiglas box filled with found and donated objects—shoes, dolls, a flag, pieces of clothing, a cross, a clock. They symbolize not only the physical destruction, but also the intangible losses—childhood, innocence, faith—national or religious—and time. A wall of granite in the shape of a wave marks the height of the storm surge. Even more telling is the dedication: not for whom but by whom the monument was commissioned. A gift donated to the city of Biloxi by ABC’s Extreme Makeover: Home Edition. The show, broadcast to millions of viewers, must have garnered millions of dollars in advertising. Even as it commemorates the experiences of the hurricane victims and the generosity of the producers, the benefits to the network cannot be ignored; it’s a commercialization of memory. Still, the monument is small compared to the giant replica of an electric guitar that looms nearby; across the street from the town green, the new Hard Rock Hotel and Casino has opened. When sunlight hits the chrome and bounces off the building, it’s the only thing you can see.

Inside, the casino offers a strange counterpoint to the collection of homely objects in the Plexiglas memorial; the walls are covered with memorabilia—all of it supposedly authentic: shoes of famous rock stars, their clothing, instruments, jewelry. The casino had been set to open just before Katrina hit, and some memorabilia washed away in the storm. There’s a small collection of what has been recovered—muddy still and warped—meant to remind us that the casinos have suffered, too.

Farther down the beach, a different kind of monument anchors the memory of the destructiveness of Katrina: live oaks that did not survive the storm. Rather than removing them, a local chainsaw artist is transforming the dead trees into sculptures that depict the native species of animals on the coast—pelicans, turtles, dolphins, herons—all shaped to suggest movement and, perhaps, hope for the coast’s environmental future.

On the first anniversary of Katrina, people gathered to remember—some at churches or community centers, others at locations that held more private significance. Aesha marked the anniversary by donating blood. Johnny, a dealer at one of the casinos—a friend of my brother’s—says that he stayed home to watch the national news. He wanted to see how the anniversary and the recovery were being understood outside the region. Then, he took a kind of memorial drive. “Just riding down the beach,” he said, “trying to find places I used to go.” This is actually a difficult feat. People still give directions in terms of landmarks that are no longer there: “Turn right at the corner where the fruit stand used to be,” or “across the street from the lot where Miss Mary used to live.” Aesha tells me there are no recognizable landmarks along the coast anymore, and I see this too as I drive down the beach. No way to get your bearings. No way to feel at home. I worry that fewer and fewer people will remember the pre-Katrina landscape, the pre-Katrina culture of the coast, and that it could be forgotten. “So many landmarks are gone,” Joe says, “replaced by something commercial. Everything seems artificial now.”

Governor Haley Barbour recently announced plans to construct Margaritaville Casino and Resort on the shores of Biloxi. Taking the place of a historic neighborhood, the project is expected to cost more than $700 million and is the single largest investment in Mississippi since the hurricane. The huge casino, hotel, and retail complex will claim prime, historic property near the Point Cadet area of Biloxi. At the same time, most homeowners can’t afford to stay. When I ask about the future of development in the area, Aesha tells me about the new FEMA requirements for housing elevation levels. “It makes rebuilding too expensive for many poor people,” she says. The new regulations stipulate that homes can only be rebuilt twenty yards back from the road, but many homeowners’ lots don’t extend that far. “Now,” she says, “it’s likely that they’ll be pushed out.”

My brother imagines a future for the coast: a resort and vacation town like Panama City. He says Biloxi will be “a nice city—but it just won’t look like the old Biloxi.” Joe thinks that meeting the cost of living will be a severe challenge to residents of the Gulf Coast. He has little confidence in the development of affordable housing. He knows only one person who lives in an apartment where the landlord didn’t raise the rent about 70 percent in the months following the storm. Instead, he sees a population of “out-of-towners”—corporations with big business interests in the ports and the gaming industry. Joe sees an upside to this in the coast’s growing diversity—Jamaican and Mexican immigrants, among others, coming for the new work. I can see his point; in a region where the vestiges of racism hang on, played out in debates about “heritage” and the Confederate flag, the arrival of newcomers signals a new coast. In their attempts to gain patronage, businesses are helping to inscribe a more liberal narrative—at least one in which the only color is money green. But people have been overwritten, too. “I’ve lost a lot of friends,” Joe says, describing a social network—a group of people with whom he gathered after work—that has been all but erased.

Some time ago—before the storm—my grandmother and I were shopping in Gulfport, and we met a friend of hers shopping with her own granddaughter. The woman introduced the girl to us, saying her nickname, then quickly adding the child’s given name. My grandmother, a proud woman—not to be outdone—replied, “Well, Tasha’s name is really Nostalgia,” drawing the syllables out. I was embarrassed and immediately corrected her—she must have meant Natalya, the formal, Russian version of Natasha—not anticipating that the guilt I’d feel later could be worse than my initial chagrin. At both names’ Latin root: the idea of nativity, words like natal, national, and native. “I write what’s given me to write,” Philip Levine has said. I’ve been given to thinking that it’s my national duty, my native duty, to keep the memory of my natal Gulf Coast as talisman against the uncertain future. In this light my grandmother’s misnomer is compelling; she was onto something.

Everywhere I go, I feel the urge to weep not only for the residents of the coast but also for my former self: the destroyed public library is me as a girl, sitting on the floor, reading between the stacks; empty, debris-strewn downtown Gulfport is me at Woolworth’s lunch counter—early 1970s—with my grandmother; is me listening to the sounds of shoes striking the polished tile floor of Hancock Bank, holding my grandmother’s hand, waiting for candy from the teller behind her wicket; me riding the elevator of the J. M. Salloum Building—the same elevator my grandmother operated in the thirties; me waiting in line at the Rialto movie theater—gone for more years now than I can remember—where my mother also stood in line, at the back door, for the peanut gallery, the black section—where my grandmother, still a girl, went on days designated colored only, clutching the coins she earned selling crabs; is me staring at my reflection in the glass at J. C. Penney while my mother calls, again and again, my name. I hear it distantly, as through water or buffeted by wind: Nostalgia.

Names are talismans of memory, too—Katrina, Camille. Perhaps this is why we name our storms.

Nine months after Katrina, I went home for the first time. Driving down Highway 49, after passing my grandmother’s house, I went straight to the cemetery where my mother is buried. It was more ragged than usual—the sandy plots overgrown with weeds. The fence around it remained standing, so I counted entrances until I reached the fourth, which opened onto the gravel road where I knew I’d find her. I searched first for the large, misshapen shrub that had always showed me to her grave; it was gone. My own negligence had revisited me, and I stood there foolishly, a woman who’d never erected a monument on her mother’s grave. I walked in circles, stooping to push back grass and weeds, until I found the concrete border that marked the plots of my ancestors. It was nearly overtaken, nearly sunken beneath the dirt and grass. How foolish of me to think of monuments and memory, of inscribing the landscape with narratives of remembrance, as I stood looking at my mother’s near-vanished grave in the post-Katrina landscape. I see now that remembrance is an individual duty as well—a duty native to us as citizens, as daughters and sons. Private liturgy: I vow to put a stone here, emblazoned with her name.

Not far from the cemetery, I wandered the vacant lot where a church had been. Debris still littered the grass. Everywhere were pages torn from hymnals, Bibles, psalms pressed into the grass as if cemented there. I bent close, trying to read one. To someone driving by, along the beach, I must have looked like a woman praying.

Epilogue: Liturgy

To the security guard staring at the gulf

thinking of bodies washed away from the coast, plugging her ears

against the bells and sirens—sound of alarm—the gaming floor

on the coast;

To Billy Scarpetta, waiting tables on the coast, staring at the gulf

thinking of water rising, thinking of New Orleans, thinking of cleansing

the coast;

To the woman dreaming of returning to the coast, thinking of water rising,

her daughter’s grave, my mother’s grave—underwater—on the coast;

To Miss Mary, somewhere;

To the displaced, living in trailers along the coast, beside the highway,

in vacant lots and open fields; to everyone who stayed on the coast,

who came back—or cannot—to the coast;

To those who died on the coast.

This is a memory of the coast: to each his own

recollections, her reclamations, their

restorations, the return of the coast.

This is a time capsule for the coast: words of the people

—don’t forget us—

the sound of wind, waves, the silence of graves,

the muffled voice of history, bulldozed and buried

under sand poured on the eroding coast,

the concrete slabs of rebuilding the coast.

This is a love letter to the Gulf Coast, a praise song, a dirge,

invocation and benediction, a requiem for the Gulf Coast.

This cannot rebuild the coast; it is an indictment, a complaint,

my logos—argument and discourse—with the coast.

This is my nostos—my pilgrimage to the coast, my memory, my reckoning—

native daughter: I am the Gulf Coast.