Miss Sinaloa came to this place in the desert to live with the other crazy people under the giant white horse. She did not belong, but then neither did the caballo. The horse stretches over half a mile in length, sketched onto the Sierra de Juárez with whitewash by a local architect. He copied the design from the Uffington horse in Great Britain, a three-thousand-year-old creation deep from the dreamtime of Bronze Age people. He said he was doing it as an exercise in problem solving (the original faces right, his faces left and is three times as large) and as a way to draw attention to the beauty of the mountains. What he did not say was what some in the city whispered: that the horse was sponsored by Amado Carillo Fuentes, then head of the Juárez Cartel, a criminal enterprise that, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), was earning $250 million a week by 1995. But, of course, that was in the golden age of peace in Juárez, when murders ran just two or three hundred a year, and at any given moment fifteen tons of cocaine were warehoused in the city, waiting to visit American noses. Those were the good old days, when life made sense—even in death.

Now, the world has changed. In December 2006, Felipe Calderón, as one of his first acts as president of Mexico, declared war on the drug cartels of his nation (the Juárez cartel is one of many such organizations in the republic) and announced his intention to use the Mexican army as his instrument. Violence exploded across the nation and the number of murders soared, but the Army has suffered almost no losses, the cartels have suffered almost no losses, and the price of drugs in American cities has remained stable or has even declined. Yet, the vast majority of politicians and media outlets claim it is a war to the death against drugs and drug cartels.

They insist that power must replace power, that structure replaces structure. And they insist that power exists as a hierarchy, that there is a top where the boss lives and a bottom where the prey scurry about in fear of the boss. But if this is simply a battle between big cartels to control this border crossing, then why are murders happening all over the city to small-time drug sellers? In 2008, there were 20 murders in El Paso, Texas, while Ciudad Juárez, its sister city just across the remnants of the Rio Grande, officially reported 1,607—and there is likely some slippage in these numbers. Murders covered up, murders unreported, murders un-investigated.

There are two ways to lose your sanity in Juárez. One is to believe that all the violence is the direct result of a cartel war. The other is to believe that any murder is unrelated to the drug world. In Juárez, the payroll for employees of the drug industry exceeds the payroll for all the city’s factories—and Juárez is the mother lode of factories; it boasts the lowest unemployment in Mexico. There is hardly a family in the city that does not have a member in the drug industry, nor is there anyone in the city who cannot point out narco mansions or new churches built with narco money. The entire society in Juárez rests on drug money, and why shouldn’t it? It is the only possible hope for the poor, the valiant, and the doomed. So a person never knows exactly why he is killed but is absolutely certain that his death comes, somehow, because of the enormous profits attached to drug sales.

There has been little notice of this slaughter in the American media. People say there are murders in Detroit, that women are raped in Washington, DC, that the cops are on the take in Chicago, that drugs are everywhere in Dallas, and that the government is a flop in New Orleans. People tell me Los Angeles is a jungle of gangs, that we have our own revered mafia, and that drugs flood Mexico and Juárez because of the wicked, vice-ridden ways of the United States. All of these assertions may be true, but they are also distractions from the deaths on the killing ground.

In the last decade, something has changed in Juárez; I feel this in my bones. The state still exists—there are police, a president, a congress, agencies studded across various government buildings—but the Mexican government increasingly pretends to be in charge and then calls it a day. Thirty thousand Mexican soldiers are said to be fighting the drug war. Yet the police have connected scarcely a body to the cartels and the Mexican army has captured comparatively little cocaine—this in a city with thousands of retail cocaine outlets. The US beefs up the border, installs high-tech towers, tosses up walls, and puts twenty thousand Border Patrol agents on the line to face down Mexico. Still the drugs arrive right on time.

And, all the while, violence courses through Juárez like a ceaseless wind, and we insist it is a battle between cartels, or between the state and the drug world, or between the army and the forces of darkness.

But consider this possibility: violence is now woven into the very fabric of the community; it has no single cause and no single motive and no on-off switch.

Violence is not a part of life; it is life.

Just ask Miss Sinaloa.

She was a teenager when the white horse was created in the late nineties, but at that time Miss Sinaloa knew nothing of giant horses painted on mountains, nor of the cartels, nor of the crazy place here in the desert. She came here in December 2005. She stayed some months and then went home to Sinaloa, the state on the Pacific coast that is the mother of almost all the major players in Mexico’s drug industry. She was very beautiful; I know this because Elvira tells me so as we stand in the wind with the sand whipping around us.

Elvira is heavy with a coarse sweater, pink slacks, dark skin, and cropped hair with a blonde tint dancing through it. A man straddles a bicycle by her side, a boy in red overalls clutches a pink purse and stares, and sitting on the ground is the lean and hungry dog of the campo. Smoke fills the air from a trash fire behind the asylum where they all work. The facility—a concrete-block structure with various rooms inside—hosts a hundred inmates. The old woman gets about fifty dollars a week for cooking three meals a day, six days a week—she says she is one of fifteen caretakers. A doctor drops by on Sundays to check on the health of the locos, and the whole operation is sponsored by a radio evangelist in Juárez.

Every five days, the staff takes the bedding from the inmates, washes it, and then comes out beyond the walls and drapes it on creosote or yucca plants for drying. The blankets now huddle in the wind like a herd of beasts—green, red, blue, violet. One is gray with a tiger and her kitten on it. My mind spins back to the mid-nineties when Amado Carrillo ran Juárez and for a spell was dumping bodies wrapped in tiger blankets. He was rumored to have a private zoo with a tiger, one he fed with informants, but this was a common legend in the drug industry. Then, for a spell, he wrapped informants in yellow ribbons as gifts to the DEA. All this happened in the quiet days of the past when the killing was not nearly so bad.

Elvira explains how people wind up in her care: “There are many brought here because they tried to stab a father, or they are addicts, or they have been robbed or assaulted and broken forever. Many of the women here have been raped and lost their minds forever. There is a thirty-four-year-old woman here who saw her family assaulted, and then she was raped and lost her mind.”

She says this in a calm voice. It is simply life.

The wind blows, the dust chokes, the white horse watches, and suddenly Elvira starts talking about Miss Sinaloa—Elvira’s exact phrase, Miss Sinaloa, because the young woman was a beauty queen with gorgeous hair that hung down to her ass—and how very, very white her skin was, oh, so white. Her eyebrows had been plucked and replaced by elegant tattooed arcs. The police had found her wandering the streets of Juárez one morning. She had been raped, and she had lost her mind. Finally, Elvira explains, her family came up from Sinaloa and took her home.

The asylum facing the giant horse is not a place in Juárez where beautiful women with white skin tend to stay. Just down the road to the east is La Campana, the alleged site of a mass grave where Louis Freeh, then head of the FBI, and various Mexican officials gathered in December 1999 to excavate bodies. The story of the mass grave was soon forgotten, however, because its source was a local comandante who had fled to the US, a man known on the streets of Juárez as El Animal. And he could produce very few bodies—each and every one of which he had murdered personally. The burying ground itself was owned by Amado Carrillo. One of his killers now teaches English to rich students in a Juárez private high school. Of course, he continues to take murder contracts between classes. Then off a ways to the southeast of La Campana is the Lote Bravo, where dead girls have been dumped since the mid-nineties.

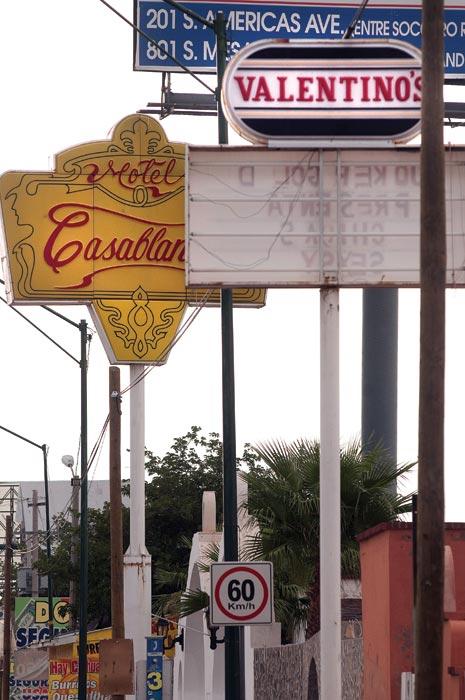

All this history comes flowing back to me as I hear the story of Miss Sinaloa. She had gone to a party with police, and then after the fun the police brought her to the crazy place. But there is always one enduring fact in Juárez: there are no facts. The memories keep shifting. Miss Sinaloa was a beauty who went to party in Juárez and was raped. Then later, the story is that she went to a party at Valentino’s, across the street from the Casablanca in Juárez, and that she consumed enormous amounts of cocaine and whiskey and became crazy, so loca that people called the police and the cops came and took Miss Sinaloa away.

The Casablanca is, of course, white, and has many rooms with parking beside each one and metal doors to protect the privacy of the cars and license plates from prying eyes. Men bring women here for sex or love or joy or whatever term they prefer. It’s so close to Valentino’s, and she has such long hair, she is so beautiful, and a fair-skinned woman is such a treat for street cops …

For days she was raped. Eight policemen in turn, over and over. Then they dumped her at the crazy place.

She had bruises on her arms and legs and ribs. Her buttocks bore the handprints of many men. There were bite marks all over her breasts. She had lost her mind.

And now she had come to the place of kindred souls.

People vanish. They leave a bar with the authorities and are never seen again. They leave their homes on an errand and never return. They go to a meeting and never come back. They are waiting at a bus stop and never arrive at their assumed destination. At times, some people keep lists of the disappeared. One such list hit 914 before the effort was abandoned. No one really knows how many people vanish. It is not safe to ask, and it is not wise to place a call to the authorities.

Still, we all love the hard look of numbers. So murders are tallied, and for fifteen years Juárez had recorded two to three hundred official murders a year. Periodically, skeletons are found on the edge of town, and these do not enter the totals. And once in a great while, homes are found in which people have been murdered and buried. Each time such a house of death is revealed there is a great to-do, the extraordinary sense of something hidden coming into the light of day. People always say they are shocked, the neighbors always say they noticed nothing amiss, the press always says the authorities are digging, digging, digging, and will soon get to the bottom of things. Every effort is made to keep this astonishing moment within the realm of order and to process the corpses so that numbers and structure can be felt and touched.

Often forensic experts huddle in these dig sites at death houses. They have no names, and only their backs are in the published images. There are few, if any, reports of their findings. They are the costume of order more than the substance of hard facts. Their bodies appear in photographs but not their faces. For that matter, the various elements of law enforcement at these charnel houses appear in the newspapers wearing masks. Only the cadaver dogs are shown with faces exposed.

And then, always, public notices of the death house and its bodies vanish from the papers much as the dead vanished from the city itself. Memory ebbs and the cavalcade of the vanished and the deceased disappears from sight and becomes some ghost column winding through the city streets that no one professes to actually see. Or the dead sit in the café where they had their last cup of coffee, belly up to the bar where they had that last drink, huddle in the wind and dust at the bus stop where they awaited their final ride.

Sometimes, the vanished never reappear. There are periods when no bodies turn up with hands duct taped and a bullet through the skull, but it is impossible to imagine the drug industry with its implicit contractual protocols ever taking a holiday from death. Sometimes the vanished never even become a name on a list. People are afraid to report their missing kin. In one instance, twelve bodies came out of the ground at a death house and yet not a single person slumbering there had been reported missing.

So, there are clearly two ghost patrols out and about in the city. Those who were murdered and secretly disposed of by the drug industry and those who vanished for some other reason and were never reported—pages left half-written, tales never fully told. Vanishings are somehow more final than executions because they are not just death but erasure—from memory, from any record of having been part of the human community.

During the season of violence that swept through the city and brought me into the circle of Miss Sinaloa, I stopped at a convenience store to buy a bottle of water. Taped below a pay phone was the photograph of a cop with the date he went missing, his name, and a phone number where someone waited for a message about his fate. It occurred to me that the city’s magical powers had reached a new level when even the police had to seek anonymous tips to find one of their own.

Certainly, the city police have learned to fear vanishing. Traditionally, officers have been required to leave their guns at the station house when they finish their shifts. But now they are publicly complaining about this practice because it forces them to travel home, like any other citizen, without a weapon. They say this policy is now unacceptable. They need their guns. They need more power.

Just down the road from the convenience store was a huge billboard soliciting recruits for the very same police force, an image of a man in a helmet with a black mask and a machine gun.

The Winter of Our Discontent

The dust blows in Juárez; the workers climb aboard white school buses for the one- to two-hour ride to their shifts. The roads are dirt; some parts require that the bus be punched into four-wheel drive. Everyone here works in a maquilladora. I look to the north and see the blue federal building in downtown El Paso and the sweep of the American city along the slope of the Franklin Mountains. I stand on the rise of the Sierra de Juárez, over the ridge from the giant white horse and the asylum. The border is hard-edged but at times the confluence of the two cities makes them seem like one. But the border perfectly divides the killing ground from the land of plenty.

José Refugio Ruvalcabla was fifty-nine on November 27, 1994, when he turned up exactly on the line—midway across the bridge between the two cities—in his Honda Accord. He’d been a state cop in Chihuahua for thirty-two years and both of his sons were with him that day. All three were in the trunk, beaten, stabbed, and strangled. The father had a yellow ribbon around his head, knotted so it seemed to flower from his mouth.

He knew where the line was and what happened if that line was crossed.

So do American political leaders since they never seem to come here.

The barrio where I stand looking down from Juárez at El Paso is part of the puzzle of the violence in Juárez. These districts are drab, dirty, and largely unvisited. Most are stuffed with people who work in the maquilladoras. Later, I am in a barrio across from the asylum. The white buses lumber past carrying the tired faces of the factory workers. The road is ruts; most of the shacks lack electricity or water. The wind pelts everyone with dust. The houses themselves are a chaos of boards, pallets, beams, rebar, old cable spools, tires, bedsprings, concrete blocks, posts, scrap metal, car bodies, old rusted buses, stone, rotted plywood, tarps, barrels, black water tanks for the periodic deliveries, plastic buckets, old fencing, bottles, stove pipes, aluminum strips, pipe, broken chairs, tables, and sofas. Like the asylum itself, the place feeds off what the city rejects.

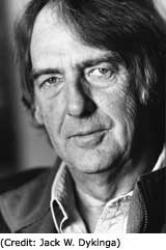

The mural depicts a conquistador. A sign says, VISIÓN EN ACCIÓN. Vision in action. But one of the N’s has fallen off. In the corner stands a metal statue of a man in armor. This is the office of El Pastor, José Antonio Galvan, the evangelist who took in the battered remains of Miss Sinaloa and gave her succor in the asylum. His office was once a drug house where addicts punctured their veins and savored their dreams. El Pastor arrived here as a street preacher raving in the calles. The local priest called him a devil. But he drew others to him. As for the devil, he fights him daily—he keeps a black and red punching bag near at hand and slams it with his fists as he fights Satan. Everything about El Pastor is vital and coarse, his language often vulgar, his feel for the crazy people visceral. He is sitting in front of me, with a mop of graying hair, a fleshy body, a ready smile—but rough edges remain and keep him honed. He has a tattoo of a good-looking mestiza. And another of a beautiful indigenous woman.

He is showing me a movie of the asylum—men beaten by police and dumped half-crazy on the streets, addled addicts with seeping ulcerated wounds, women who will never remember what happened to them and never want to remember.

I stare at the ruined faces in the video and ask, “Does your congregation support this work?”

He smiles, points to the screen, and says, “This is my congregation.”

El Pastor spent sixteen years as an illegal immigrant in Los Angeles, where he learned to be a crane operator. He did lots of drugs and drank lots of alcohol and earned sixteen dollars an hour. Then, in 1985, he was reborn. He returned to Juárez to do God’s work, mainly preaching on the street to drug addicts. In the winter of 1998 El Pastor says he was driving through a bad storm when he saw a mound on the street and swerved just as a man stood and shook off the snow that had fallen and covered him. “I was driving that day and singing to the Lord and it was snowing. I said, ‘Lord, I’m working with you,’ and the Lord pulled my hair.” So El Pastor rounded up friends and spent the day gathering the wounded of the streets—brain-damaged addicts, ruined gang members, everyone left out in the snow in a city without mercy. That is the moment when he began scooping the crazy people off the streets, the moment when he began creating his asylum in the desert.

“Oh, they smelled bad,” he says, “covered with shit and all that.”

Originally, he came out here and lived in a hut with his wife. He had two donkeys for gathering wood. He started stacking up blocks and bricks. This went on for three years. The police would bring the rejects of our world—whores burned out by drugs and men’s lust, illegal immigrants kicked back by the US because they did not want to tend to their damaged minds, topless dancers who had lost that half step and were discarded, street people who had sniffed so much glue and paint they were now residents of oblivion.

El Pastor now houses and feeds a hundred of them. He walks me around and shows me his expansion dream that will give him the capacity for 250 souls. He will have the patients making bricks—those who can still function well enough to mix up mud. He will sell these blocks and so give the patients a kind of dignity and himself some cash flow to pay for the medicines they require in order to bottle up their rages. At present, he must raise ten thousand dollars a month on the radio simply to meet the medical, food, and staff costs of this crazy place he has created.

But now El Pastor is jubilant because he is talking about Juárez.

“I love Juárez,” he says, “I know it is dirty and very violent but I love it! I grew up in Juárez. I love it. It is a needy city and I can help my city. I can make a little difference.”

I am looking in at Miss Sinaloa’s cell in the asylum. A small mattress fills it and at the foot of the mattress is a yellow five-gallon bucket for defecation and urination. The walls are white tile, because patients tend to smear their feces on surfaces. The door is solid metal with a tiny slot because they tend to throw their feces at the staff. Plaid blankets cover the mattress.

This was her home for at least two months. No one could reach her. She raved; she was very angry. In part, she was locked up to protect her from the other patients who craved her fair skin and beauty. And in part, she was locked up because she would go berserk without warning.

And she was bald. The staff had to cut off her long, beautiful hair because it posed a risk here. Other patients have a tendency to take long hair and strangle the person with it.

At first, Miss Sinaloa was very violent. She cried constantly and threw things. So the staff gave her pills, and she slept for two or three days. When she woke, she was calmer. She told everyone in the crazy place that she had won a contest, that she was a beauty queen and also a model. She said that she had known oh so many men who wanted to fuck her, but she had known no one who truly loved her for herself.

Her beauty became a problem. When she was let out of her cell into the yard, she stood out in her glory. El Pastor says, “She was like the last Coca Cola in the desert, and so proud, and the other ladies were jealous.”

She would spend all day doing her makeup, doing it over and over and over. She was very clean. Each morning she made the bed in her tiny cell and washed all the walls, scrubbing endlessly.

Ramon was a twenty-five-year-old drunk who had wandered into the crazy place and earned his keep serving meals. He was a homely man—El Pastor thought he might be the ugliest man in the world. He took plates of beans to Miss Sinaloa in her cell. She fell in love with him, and he fell in love with her. Ramon had never had a girlfriend before—and he was dazzled by even this ghost of the Miss Sinaloa who had arrived in Juárez to party at Valentino’s.

“How wonderful that this happened to me,” she said. “Because of it, I was able to find you, the most beautiful creature ever created by God.”

El Pastor overheard Miss Sinaloa whispering her love to Ramon and was alarmed. Then he noticed love marks on Ramon’s neck and dismissed him.

Miss Sinaloa regressed and soon returned to her deep madness. She denounced El Pastor for ruining the great love of her life.

El Pastor stares with me into the cell—maybe nine feet by five feet.

A small, retarded man stands next to me clutching a children’s book. It is in English, but then, he can’t read any language. He hands it to me, and I flip through: “One windy day during the harvest time, Quail sings a song—just as Coyote walks by. ‘Teach me your song, or I shall eat you up,’ cries Coyote. But Quail’s song is no ordinary song, and Coyote may end up swallowing more than he bargained for …” Not long before, the retarded man murdered another patient.

“You can’t do anything to be safe here,” El Pastor explains as we stand in the yard with eighty of the maimed milling about us.

“Heroin in the city is twenty-five pesos.”

This means less than $2.50 a hit.

“Cocaine,” El Pastor continues, “is everywhere here and cheaper than marijuana. And now they smoke cocaine with marijuana. We’re talking about people eighteen to twenty-five now, the people who get executed. They are ghosts, human trash walking naked in the city.”

After two months or more, Miss Sinaloa seemed to recover some of her mind. El Pastor estimates that she eventually regained 90 percent of her sanity. He located her relatives, and her family came up from Sinaloa. They must have been surprised that she was alive. I am. After such a frolic, death would not be unusual, and Miss Sinaloa would be just one more mysterious dead woman in the desert on the outskirts of Juárez.

But something saved her—perhaps her madness set her apart.

And so she came here to live with people considered beneath even the dirt of Juárez—people from the streets, people rejected by state mental institutions, people beyond the help of families, people who slept on sidewalks and ate out of garbage cans.

Miss Sinaloa claimed that she knew many languages, but she never spoke them. She would sing all the time, but she sang badly. Her favorite songs were very romantic. She moved around the crazy place like a queen. She read the Bible a lot. She remains a legend at the crazy place. El Pastor decided that 5 percent of what she said was true and the other 95 percent was her imagination.

That was the world of Miss Sinaloa, a place of dreams and songs, a place for a beauty queen to rule. She drew a lot—mainly lines and spirals. And lips, lots of kissing lips.

She dressed well, always a blue dress that showed her legs. And high heels—she navigated the asylum in stilettos.

To El Pastor’s horror, she said a lot of bad words. He thinks maybe the rapes made her talk this way.

He prayed with her, and she closed her beautiful brown eyes.

She never mentioned her family.

She only talked about her beauty. Nothing else really, just her beauty.

She was Miss Sinaloa, after all.

Miss Sinaloa and I have passed into a new world where violence is the way and death is life and no one is in control. The only one who seems to understand all this is El Pastor, but he is crazy for Jesus—his bumper sticker says REAL MEN LOVE JESUS. This is a way station that Miss Sinaloa and I have skipped. Platitudes deny our sparkling new world. You can believe in your war on drugs, in your battle against cartels, in free trade, in Homeland Security, in the war on terrorism, in seatbelts, your war against death and taxes, condoms, bottled water, the right scotch, stylish shoes, the internet, virtual reality, liposuction, your official states and statesmen, and ah, the girls walking by dressed in their summer clothes. You don’t have hand prints on your ass and bite marks on your breasts and fragments of your mind that tell you of visits to places the presidents never bother to mention.

I prefer the company of Miss Sinaloa, her skin so fair, her hair coming back and her damaged mind more knowing than the governments that pretend to rule us all.

The black boots came with Miss Sinaloa. She arrived that December afternoon with shiny black boots reaching almost to her knees, the heels thick, the surface acrylic as it threw light back up toward the heavens. The rest of her was skin—skin with bite marks all over her breasts, skin with handprints all over her ass. There were marks of beatings also.

That was weeks before, when she had hair flowing all the way down her back but had lost all of her wardrobe, save those boots. And lost her mind.

I sit here looking at a photograph taken in the yard of the crazy place. She had been in her cage for some weeks and her hair had been shorn. She was calming down and was allowed out into the yard at times, a kind of safe-conduct moment in which she struggled to rejoin the human race.

She is standing in the bright sunlight, the boots gleaming, and she wears a satiny green dress and a black leather jacket. She holds a microphone in her right hand, and she is singing love songs. Behind her is a black amplifier, and behind the equipment are her neighbors in the crazy place, and they look here, and they look there, and they pay no attention to Miss Sinaloa singing of the heartaches that women must endure as they seek love in the world of men.

Her face is round and perfectly made up. The cheeks almost shine, the lips underscored with liner, the eyebrows narrow and finely stated. Her body is solid, and to foreign eyes might even look fat, but here in her native country she looks good, a woman with some flesh, a woman a man can get a hold of as the night passes on sweat-soaked sheets. She is battered, she is still healing, she is half crazy, but it is clear to even my ignorant eyes that Miss Sinaloa is back, and that to her men are simply creatures God created to worship her.

One member of her audience sits with head bowed and hands clasped between his knees. Another man wears a huge wizard’s hat. A short man in a beige sport coat looks out with an idiot grin.

Miss Sinaloa sees none of these people any more than they see her. She sings in her own space; she creates with her voice a world of perfume and fine whiskey and beauty, and, of course, a world of desire and that desire is for Miss Sinaloa. She is a goddess, and no one can question this fact. She has escaped the infidels, those who did not believe in her powers but saw only the holes in her body that could be fucked.

She sings because to fall silent is to die.

Even here, the world is about love, or the world is about nothing at all.

I have learned many things from her and because of this, I too love her and her songs.

I think at times I need her music even more than she does.

Those red lips mean very much in a world of dust and blood.

We seem to take the dust for granted, to take the drugs for granted. And to take the killing for granted. Soon we will expect our own murder and not even worry if it will arrive on schedule.

That is the way El Pastor was years ago when he moved out into the desert and built a hut as the initial act of his decision to create an asylum for the destroyed people. He had two burros; he gathered dead wood in the sands for a fire.

He looked up at the mountains where the giant Uffington horse spread Celtic mystery over the Sonoran desert. Some days the wind blew, and the sand came up and hid the mountain. But there were times, wonderful times, when the stars came out at night, and the sun fell down like honey on his mission.

These were the wonder days for El Pastor. He had nothing; the hut did not even have a real roof, just canvas stretched over the adobe walls. He was living the life of the early Christians, and I’m sure his soul was full of Jesus and his mind full of anxiety.

He noticed that a giant iguana had been sketched on the mountain in the same manner and scale as that of the Uffington horse. Everyone knew and whispered that the big horse was the gift of Amado Carrillo to the mountain. And, of course, El Pastor knew that the big iguana was the symbol of the Juárez cartel, a kind of trademark, and having it sketched on the mountain told everyone that the city belonged to them.

At night, but also sometimes during the day, El Pastor saw helicopters landing right by the iguana.

So one day he went up there to see what was going on.

Men with guns told him he did not belong there and that he should not come back. Perhaps the fact that he was a man of God spared him from a worse punishment than a verbal warning.

No matter, El Pastor went back to his work and prayer and eventually built the compound that became the temporary home of Miss Sinaloa.

The giant iguana itself became like the dust storms and hot days, something so commonplace as to be beneath notice. Just part of the natural landscape of this city of death.

El Pastor prays for me, a thankless task for which I thank him.

The year has not been easy for El Pastor. He has watched his city die around him. He has had men come with guns demanding money. He was at a stoplight one afternoon and saw a man executed three cars ahead of him.

I urge him, “Tell me what the slaughter of 2008 means.”

He says: Not even in the Mexican Revolution did they kill so many in Juárez. This year of death shows the brutality inside the Mexican government—death comes from inside the government. Not from the people. The only way to end the violence is to let organized crime be the government.

The crime groups are fighting for power. If the toughest guy wins, he will get everything under control.

Now there is no respect for the president. People now say to the president, “Fuck you, man.”

I am a miracle, but I am not a martyr. I don’t want to be killed.

We sit outside his house. His red car stares at us with a front plate that says, WITH GOD, ALL THINGS ARE POSSIBLE.

As we enjoy the blue sky and the warmth falling from heaven, more die in the city.

That is the answer.

The sun. And the blood.

There is a way out—though to outsiders this way may look like a violent fantasy. The cholos on the corner with their hard, empty eyes, close-cropped hair, baggy pants, and sullen faces have a dream. It is of exercising power through killing, having women because of money, wearing tattoos as billboards of their ambitions. And of dying, and dying young and without warning, and for reasons they can barely say or comprehend—something about honor, or turf, or something they can’t put words to. There is no point in discussing an alternative future because the future is a place they cannot imagine or feel or crave, so an alternative is beyond words or meaning. All the nostrums of our governments—education, jobs, sound diet—mean little here because they never happen to anyone. At best, the way out is a lottery ticket. Or the fame and savor of a violent death.

I meet these people with dreams. They take old cars and make them mosaics with steer horns sprouting from the hood and that wa-wa horn shouting out, the driver with glazed eyes and a leather hat roaring with laughter as he cuts through the fiesta. Sometimes they create sculptures or paint rocks outside of towns. Sometimes they write drunken poems in the cantina or scrawl murals of distorted beings in cheap pigments. But always they dream and drift into a place called fantasy.

Listen to the sensible people, the governments who have told you since before you were born that everything is getting better, and forget about those failures—they are bumps on the road, and the road leads to Shangri-la, to bright, light-skinned children, good jobs, fine schools, public health, women who lick your toes, men who respect your body, safe streets, and nights in which the darkness holds no dread.

Or consider the market forces, the magical pulse of a global economy, hitch a ride on an information highway, become part of a giant apparatus that is towing us all toward the golden shore, and, yes, the slogans come and go, but don’t you see the future is beckoning and will make you sound? And you’ll have a bathroom and the toilet will flush every single time. Lady, you will be beautiful and your hands will be smooth and soft and never will a single wrinkle touch your face, nor will your breasts sag a single degree.

Given the choices, what would you do? I’d kill to get in the gang, I’d put on the high heels and the perfume, I’d pick up the guitar, I’d go through the wire, I’d open the bottle, I’d sniff the glue, I’d say the lovers are losers, and I’d certainly piss on the winners, that anointed few. And I’d maybe kill in Juárez, but far more certainly, I would die in Juárez. With a shout and a scream and a head full of dreams.

And I am sitting with Miss Sinaloa who should have known better. I can hear the voices of reprimand in my ears that announce with certainty that sensible women of good features do not go to private parties in Juárez where many men will gather whom they do not know—yes, I can hear these wise voices telling me the facts of life. I say dream, I say fantasize, I say escape, I say kill, I say do not accept the offerings of the cops and the government and the guns that have slaughtered hopes for generations and generations.

I say fantasy.

I say go to Juárez.

I say, Miss Sinaloa, will you take my hand?

I have been to the far country with her and now I am back. The air of morning tastes fresh; the sunrise murdered the night and now the light caresses my face. I chew on ash and bone, what has become my customary breakfast. I drink a glass of blood for my health.

She does not speak. I no longer listen.

The far country lingers on my clothes and in my hair. I can still smell it here in the morning light. I have brought her with me and now we will live together for the rest of my days.

Her lips gleam a ripe red, and a sweet fragrance floats from her white skin.