Radovan Karadžić was once feared as the Butcher of Bosnia. Now you can tour his favorite hiding places.

Giggles. The Serbian journalist sitting next to me leans over and whispers into my ear, “This is embarrassing.” One of the cameramen—there are four—asks Draga, our tour guide, to please repeat her opening words, so he can get her on film. She complies cheerfully. The microphone crackles in her hand, strangely doubling her voice in the small space of the passenger van. Welcome to the Pop-art Radovan Tour! In the next few hours we’ll visit the places where Dragan David Dabić, also known as Radovan Karadžić, lived and where he spent most of his free time. We’ll sample some of his favorite food. I would also like to mention that this is not a political tour, so any questions regarding politics will not be answered. Giggles again. This is embarrassing.

Packed with hungry journalists and bearing the outsized lettering SERBIA: EUROPE’S LAST ADVENTURE, our sightseeing van speeds through the wet streets of Blok 45, a working-class neighborhood in east Belgrade. Fine-grained drizzle smudges the view outside. The four cameramen look dejected. Drab apartment buildings huddle under drab skies, and only the occasional billboard or McDonald’s sign adds any hint of technicolor. Human shadows under shadowy umbrellas tap-dance in a silent musical. Unreal city. It is so simple to blend in here, to become nobody. The saint and the criminal might be one and the same: a white-bearded man dressed in plain black clothes.

Radovan Karadžić must have enjoyed being nobody. After so many years under the limelight of NATO, UN, EU, CIA, and ICTY, he was probably getting a bit sweaty and fame-weary, eager to step down from the stage and hide among the dark mass of anonymous spectators. To play “the Osama bin Laden of Europe” is not an easy role, especially when those who know you best would tear you to pieces if they chanced to meet you in the street. That was probably the reason why Radovan decided not to wait any longer, but to do the job himself: The explosive bouffant was dismantled into a humble and harmless ponytail; the face, once so carefully clean-shaven, regained its thick natural growth. Large spectacles replaced the military binoculars. Of course, the name, the good name that is better than precious ointment, needed some change as well: Radovan, the one who is radostan, joyful, became Dragan, drag, beloved. The second name, David, was Dragan’s etymological Hebrew twin. Beloved beloved. Radovan left the house of mirth not to go to the house of mourning, but to the house of love. Love that was as strong as death.

Radovan Karadžić—Supreme Commander of the Bosnian Serb armed forces, President of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, architect of the Siege of Sarajevo, and, along with Ratko Mladić, mastermind of the Srebrenica massacre—died somewhere in Bosnia to be miraculously resurrected in Belgrade’s Blok 45 as the 3D tabula rasa Dragan (David) Dabić, an old man with immaculately clean hands. A self-styled specialist in alternative medicine, Dr. Dabić claimed he could heal ailments of mind and body (asthma, addictions, sexual impotence and infertility, diabetes, psychological problems, stress, depression, attention deficit disorder, autism, multiple sclerosis) with the aid of an invisible power he called Human Quantum Energy. On his personal website www.psy-help-energy.com (for he didn’t spurn technology, despite his belief in nature’s ways), he explained: “We are energy beings. We undergo various energy processes that control the functions of our body and take place under the influence of higher energy forms (cosmic energy, prana, orgone energy, quantum energy, the Holy Spirit …). The energy is in us and all around us, being the main source of our health and welfare.” Dr. Dabić believed he had a gift, some version of the king’s touch, which allowed him to control that energy and restore its proper equilibrium in the sick patient, thus eradicating the root causes of disease. In addition, he preached tihovanje, or peacefulness, a little known form of Christian Orthodox prayer. “Our tihovanje and eastern meditation techniques,” he wrote in an article for the Serbian journal Zdrav Život (Healthy Life), “are similar in essence and differ only formally, as tihovanje is practiced by monks rather than celebrities.” True, once upon a time, Dragan Dabić had been a celebrity himself, but strictly speaking he was just a monk now. “Spiritual explorer” was the title he liked best.

Keeping a website, writing articles for medical journals, giving occasional lectures to crowded auditoriums: Radovan Karadžić never actually left the spotlight. Despite his new enlightenment, it was too difficult for a renowned political actor like himself to renounce vanity altogether. He had always wanted to be at the center of attention, whatever the cost, whatever the means. So he simply took up a new stage: the Aristotelian tragedy turned into a medieval mystery play; the epic hero metamorphosed into a saint.

The saint’s purloined identity was in plain sight, yet nobody managed to see through the obvious disguise. There was no disguise. Whenever asked for his contact info, D. D. Dabić would readily offer his calling card, complete with two telephone numbers and an e-mail address. (In the meantime, the real Dragan Dabić, a sixty-six-year-old retired construction worker from the small Serbian town of Ruma, had no idea he was being somebody else.) This doppelganger, this double Dabić, bought low-fat yogurt and whole-grain bread from the local grocery shop. He sipped red wine and chatted with people at the local bar. All the kids in the neighborhood knew him as Father Christmas. Rumors circulated that one of his disciples, a pretty woman in her fifties named Mila Damjanov, was his secret lover. She later denied the allegations, telling The Daily Telegraph she could have nothing but respect for her favorite guru. “He was an authentic person. I never doubted his identity or professionalism. I can’t reconcile the two personalities, the one of Karadžić and the other of the man I knew. For me there is only one person, only Dr. Dabić. I believed in him completely.” Goran Kojić, the editor of Zdrav Život, agreed: “David Dabić was a kind man, with good manners, quiet and witty. I’m not talking about Radovan Karadžić. I’m just talking about the person I met.”

Even with the riddle finally solved, many people who had known Dabić still found it difficult to accept his split identity. The strange case of Dr. Dabić and Mr. Karadžić sounded too much like a work of fiction to be true. The performance was too “authentic” to be a performance. Or could it be that those around Dragan Dabić were too willing to suspend disbelief? In one of his articles for Zdrav Život he had written: “It is considered that the senses and the mind can perceive only a fraction of existence, and everything else is a secret and a mystery, which for us is unavailable through the five senses, but is available in an extrasensory way.” Where was the intuition of his disciples? Hadn’t they learned anything from him?

In fact, it is misguided and naïve to think of Dabić’s religious mysticism and Karadžić’s lethal nationalism as manifestations of two wholly unrelated phenomena. During the war in Yugoslavia, religion assumed paramount importance, serving as the most unambiguous marker of ethnic affiliation. Bosnian Muslims were easy targets for Serb Christians. Tito’s secular communism had managed to incinerate the deities of the past, but the phoenix that hatched out of its cold ashes was fiercer and stronger than ever. Sworn atheists suddenly grew into blood-thirsty zealots. Ethnic cleansing meant, among other things, the desecration of mosques, or churches, or cathedrals. Religious propaganda drove a wedge between the peoples of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and created divisions where before there had been none. It was the most powerful political weapon and set off the worst kinds of atrocities.

Differences of doctrine hardly mattered; very few people, whether Orthodox Christian, Muslim, or Catholic, could name even the main tenets of their professed faith. The Balkans have never cared much for theological subtleties, and belief is often received on an ethnic and cultural level—where dogma interbreeds with superstition, occult philosophies, and a taste for things supernatural. By calling on their invisible mandate, the leaders of the warring parties offered justification for their irrational policies while avoiding personal responsibility, and here Karadžić was no exception. As the first president of the Bosnian Serbs, he sought to inflame nationalist sentiments through the introduction of a highly ritualized, ethnically-specific Orthodox Christianity. Though as a young man he had never expressed any interest in God, he became most devout once he stepped into office. To be a Serb one had to be a believer; to be a believer one had to be a Serb. The basis of that religion was not the Bible, but a mythologized version of Serbian history. Thus, a civil servant like the president could acquire a mystical aura as an agent of historical change. And Karadžić brazenly exploited the appeal of mysticism to achieve his political objectives.

Playing the sage, Dragan Dabić did not renounce his past—he merely recaptured it in a different way. After the erection of concentration camps and mass executions in the name of God and greater Serbia, even the most benevolent religious mysticism could never be politically neutral. It was stained with too much blood. Tihovanje, as peaceful as it sounded, was not that far from genocide.

On the left-hand side you see a little market, where Dr. Dabić bought his fruit and vegetables during the weekends. And this is the bakery shop, where he used to buy potato pie.

I first read about the Pop-art Radovan Tour on the front page of the Serbian daily Politika. Soon after Karadžić’s July 2008 arrest and extradition to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague, a local tourist agency, Vekol, had decided to cash in on his renewed notoriety by organizing trips to the Belgrade sights Dr. Dabić used to frequent. In that same article Tanja Bogdanov, the agency’s manager, tried to justify her controversial venture: “In the last ten years Serbia has become known for its war criminals and dictators. There’s a great interest from tourists to see the houses of Slobodan Milošević, Tito, Arkan, and Radovan Karadžić.” Besides, wasn’t Russia exploiting the commercial power of comrade Lenin’s mummy? Didn’t tourists in London go on a Jack the Ripper walk? If Radovan Karadžić had tourist value, then few people in Belgrade seemed to care what exactly he had done. He was just a stepping stone, an instrument in the service of concrete economic and political objectives (he had always been that for Milošević). After all, it was the Serbian government itself that a few months earlier had, out of the blue, handed him over to The Hague, hoping for a faster route to European integration. No need was seen for reexamination of Karadžić’s criminal record—that was completely irrelevant. Hero or villain, his status depended on the variable price on his head. The $5 million reward offered by the US Department of State had simply not been enough.

For many Serbs from Belgrade Radovan Karadžić was hardly Serbian in the first place. Born in the mountains of Montenegro, the greater part of his life spent in the mountains of Bosnia and Herzegovina, he was somebody from “across the Drina,” a country bumpkin, whose ethnicity happened to be Serbian by a freak accident. “Karadžić achieved a mythical aura here because he was from somewhere else,” said Aleksandar Vasovic, a correspondent for the Associated Press. In a city that did not witness the horrors of direct military action until the 1999 NATO bombing, the figure of Karadžić, like the war he had helped mastermind, had always felt somehow distant and foreign, the stuff of enchanting fairytales or frightening legends. Some Belgraders had indeed volunteered to serve in Karadžić’s Bosnian Serb army, but the majority had stayed in front of their televisions, looking at images of slaughter and worrying about the economy. Throughout the conflict Slobodan Milošević had been insistent that the events in Bosnia and Herzegovina amounted to a civil war that had nothing to do with Serbia, and most people in the capital gradually came to accept that version of history. Bosnia and Herzegovina remained an exotic territory in Belgrade’s urban imagination, a remote region both dreaded and cherished, and, like Kosovo, little understood. That is why, when it was revealed that Radovan Karadžić, one of the men chiefly responsible for the ghastly war that had ravaged Yugoslavia and destroyed the lives of so many of its citizens, had spent the last several years residing under a false name in Blok 45, it came as a blow for almost everyone. Neither the enormity of his old transgressions, nor his newly minted identity astonished Belgraders so utterly, as much as the fact that a fabled creature like Karadžić, who supposedly belonged to another realm, in a galaxy far, far away, had been found on this side of life, amid the normal folk of the capital. It was a detective story with a twist of magical realism.

The initial reactions of shock and surprise soon gave way to tabloid delight. Beneath the surface of politics was a feeding frenzy for quotidian gossip: the music Dr. Dabić listened to (Pavarotti), the food he consumed (lots of vegetables, low-fat yogurt, potato pie, pancakes), and his sexual orientation (the police allegedly found a gay-porn video in his apartment starring DDD himself). Old issues of Zdrav Život that featured articles by “the doctor” quickly sold out. Friends and neighbors vied to share their stories with the press. The fetishistic excess of information inevitably devolved into irony. A few days after the arrest somebody created a hilarious spoof of Dragan Dabić’s website that included “10 favorite ancient Chinese proverbs as selected personally by Dr. Dabić.” Folk humor and jokes began to flood Serbian Internet forums. Here is a good one: “After getting plastic surgery in Moscow, Radovan Karadžić decides to move to Belgrade. Nobody recognizes him, but an old lady. ‘Hello, Radovan,’ she says. Distressed, he travels back to Moscow for yet another surgery. Back in Belgrade the same thing happens: the old lady recognizes him. After a third and final surgery, an extreme makeover, he returns to Belgrade more confident than ever. Not a single person takes notice of him, until he meets the old lady. ‘Hello, Radovan,’ she says. ‘Ok,’ he says, ‘how did you recognize me?’ And the old lady: ‘I’m Ratko Mladić.’”

In the cosmopolitan and intellectually sophisticated atmosphere of Belgrade it was not that difficult or morally awkward to treat Karadžić as the butt of a joke. Unscathed by the war, people could afford to look at a war criminal with ironic detachment. The thousands of posters of his face, obsessively pasted all over the city, may have been intended to stir up nationalistic sentiment, but between Coca Cola neon signs and Costa Coffee outlets they rather resembled Warhol’s prints of Chairman Mao. The kitschy souvenirs—Karadžić T-shirts and buttons—sold by downtown street-vendors, were supposed to be a declaration of Serbian pride, but came out in Belgrade as its exact opposite, a parody of itself. The Pop-art Radovan Tour just seemed like the latest iteration of this idea, yet it remained fuzzy: was the tour intended to battle virulent nationalism by treating Karadžić as just another commodity in a world of mass tourism, or did it aim to vindicate and lionize his personality?

In the Madhouse—Luda Kuca—the walls are painted baby pink; the tablecloths are royal purple. The place is tiny, like a private chapel. Iconic photographs line the walls: Radovan Karadžić in a suit and tie; Ratko Mladić in combat fatigue; Slobodan Milošević in a suit and tie. Politicians and generals, generals and politicians—the saints of the Madhouse. To that pantheon of familiar faces another one has been recently added. It is a watercolor of a white-bearded man wearing a brown coat and a black beanie: Dragan David Dabić.

The Madhouse is a nationalist-theme bar in Blok 45, where Dr. Dabić liked to unwind after a busy day of healing patients. He would buy a glass of cheap red wine, Bear’s Blood, take a seat under his own portrait, and chitchat with the local drunks. “I knew him as Dr. Dabić,” a guy named Pero tells me, his speech slightly slurred. “I’d see him buy drinks here; I’d see him on the bus. For me he was the old professor. He was a fine person. A very memorable person, very nice.” Pero seems unfazed by the cavalcade of journalists—it must be a common sight. Like the other customers of the Madhouse, he has now become part of the Pop-art Radovan Tour, holding the hem of Karadžić’s mantle by no choice of his own. He will probably never again receive so much attention in his life, so he takes his time to sip his wine and savor his fame. Miško Kovijanić, the proprietor of Luda Kuca, shares the general good mood. Pleased with the rising number of affluent visitors and the free publicity, he stands behind the bottle-lined bar with a smile on his face. The jingoistic decorations have paid off after all. From his prison cell in The Hague, Radovan Karadžić has secretly rewarded the bartender for his loyalty.

With all the journalists finally squeezed in the Madhouse, Miško gets up in front of the cameras and, clearing his throat, prepares to give a speech. The moment seems propitious.

“Radovan Karadžić was a hero and a great person,” he opens with pomp, like Pericles eulogizing the Athenian dead. “One day his name would be engraved on the pages of Serbian history. And those who betrayed him,” he pauses for a second here, as if groping to find more damning words, “would be a stain on that history. I’m very happy that Radovan Karadžić felt comfortable here, in our company, in this house. He was a man of real spirituality and we learned a lot from him. He was very humane, although people think of him as a criminal.”

“What did you learn? Give us an example,” a no-nonsense blond woman working for Hungarian television asks him, sticking the microphone right in his face.

“For example,” Miško replies with utmost seriousness, “there was a beehive right around here. Some people were frightened, and wanted to get rid of it. Then Radovan Karadžić came over and said, ‘Do not kill the bees, children. They are also God’s creatures.’ And then he removed the bees to a safe place, without killing a single one of them in the process. So here’s an example of the type of person he was—not a murderer but a savior.”

While all are attending to the edifying parable, a drunken man staggers out of the bathroom and, facing a nearby Milošević portrait, makes the sign of the cross before slipping unnoticed back to his table. “Why didn’t you cross yourself in front of Karadžić and Mladić?” his buddy asks him. “Because they’re alive,” he answers.

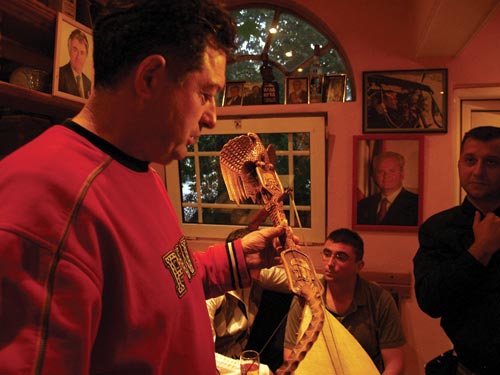

The local Pericles has finished his sermon, but he has more stories to tell. From the side of the bar he picks up a gusle, a one-string wooden instrument that traditionally accompanies the recitation of epic poetry. It is the same gusle Dr. Dabić used to play from time to time during his visits to the Madhouse. “This is an old Serbian instrument for accompanying epic songs about the great battles and bravery of our people,” he explains like an auctioneer at Christie’s. Then realizing the word “battle” might be misconstrued by some of the tourists, he feels obliged to add the traditional footnote about Serbian victimization. “But Serbs have never attacked others. They have always defended their beautiful native land from the aggression of foreign powers—the Byzantines and the Crusaders and the Ottomans. Radovan Karadžić was a great Serb, a great patriot, a man who never hated anyone. One day, when he returns here, this gusle will belong to him. Or, God forbid, if he doesn’t come back, it will be passed on to his son Aleksandar.” While giving his lecture, Pericles cradles the gusle in his hands and strokes it gently as if it were a newborn baby.

Karadžić had played the gusle and recited ancient Serbian epics since childhood. There still exists archival footage of him drawing the bow with mad energy and singing about “thirty chieftains drinking wine among the vast crags of Romanija mountain.” During the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina nationalists saw the gusle as the genuine symbol of Serbian ethnic identity—no matter that most Balkan peoples had some version of that instrument. What had once been a dying tradition practiced by a few illiterate peasants underwent a huge revival in the early 1990s. The gusle was the Serbian counterpart to the Highlands’ bagpipe. Its screeching whine called back a romantic past of military conquest, of valiant kings and warriors, of love and betrayal. In Ivo Andrić’s epic novel The Bridge on the Drina, one of the masterpieces of Yugoslav literature, it is the mournful sound of a Montenegrin’s gusle that resurrects historical memory, awakening the Christians to their lot as slaves under the cruel Ottomans.

In the mid-1930s the American linguists Milman Perry and Albert Lord traveled to Yugoslavia to record and interview a number of gusle-playing bards, and they came to the conclusion that epic poems, including the ancient Homeric ones, were orally composed with the aid of special verbal formulae—“swift-footed Achilles,” “man-killing Hector”—which poets memorized and then rearranged during performances. Epic bards were like jazz musicians, who improvised with a standard set of musical phrases.

Like a real bard, bee-loving Karadžić played the gusle in the Madhouse, shuffling back and forth the formulae he knew so well by heart. It was the exact same art he had employed skillfully throughout his career as president of Republika Srbska, the breakaway Serb region of Bosnia and Herzegovina: rearranging stock phrases, political clichés, nationalistic sound bites. The Bosnian Serbs had been Radovan Karadžić’s true gusle, and the poem he composed proved one of the twentieth century’s bloodiest epics.

Luckily, in 2008, his only remaining audience were a couple of old drunks on the outskirts of Belgrade.

Back in the warm van, everyone feels relief. The sky is still overcast and sepia-colored, but this whole charade should be over pretty soon. Then the all too familiar voice of the tour guide comes doubled through the speaker system. We’re driving along the route of bus 73, which Dr. Dabić often rode to the Zemun district and the pancake shop Pinocchio, where he bought pancakes. Now you’ll have the opportunity to taste why.

We file out of the van again, listless and sleepy, our craving for food dulled by the Bear’s Blood. Dusk has already settled over Belgrade and the cars have turned on their headlights. Some of the somber cameramen don’t even bother to bring their equipment along. There is nothing to shoot anyway. Pinocchio is an ordinary take-out joint. Painted on one of the windows is a garish image of the wooden boy whose nose grew longer every time he told a lie until he couldn’t turn around in the room. “There are two kind of lies, lies with short legs and lies with long noses,” the fairy tells Pinocchio. “Yours … happen to have long noses.”

It seems unfair that Dr. Dabić, one of the most gifted liars to come out of the Balkans, had neither short legs, nor a long nose. Stopping by Pinocchio’s to buy pancakes, he probably never noted the irony. Or, more likely, he never thought of himself as a liar. To trace Karadžić’s career is to assume as much. Psychiatrist, poet, politician—his life in Bosnia had been a series of deft metamorphoses. “In every environment Radovan had a different face,” one of his former friends told the makers of the recent documentary The Life and Adventures of Radovan Karadžić. The dream of the ragged boy, who at sixteen left his hamlet in Montenegro for cosmopolitan Sarajevo, was to become successful some day in something, anything. When psychiatry and poetry failed him, time came for politics. His turn to virulent nationalism in the early 1990s did not arise out of any long-standing ethnic hatred or ideological commitment to the principles of ethnic separation—in fact, he had had a number of good Muslim friends in Sarajevo—but was rather the product of narcissistic ambition that saw in warmongering its best opportunity for advancement. Like Milošević, Karadžić was a protean creature, who shape-shifted according to circumstances. To search for his “essential” self would be an exercise in futility.

It might not be too far-fetched to say that Dragan Dabić was not a false identity as much as another phase—another face—in the life of Radovan Karadžić. Falsifying the truth had been his specialty, no doubt, but the puzzle lay in the fact that he had come to treat his own falsifications as uncontested reality—the painfully familiar story of the delusional ruler poring over his maps. After a meeting with the Bosnian Serb leader in the mid-1990s the journalist Mark Danner astutely observed: “Dr. Karadžić, clearly a very intelligent man, had mastered the fine art of construing and delivering with great sincerity utterances that seemed so distant from demonstrable reality that he left no common ground on which to contradict him.”

But did Dragan David Dabić believe in Dragan David Dabić? Quite likely. It must have been impossible, of course, to forget that he was still one of the most sought-after war criminals in the world, and no amount of human quantum energy could change that. Yet, his dedication to the study of alternative medicine was so sincere, he pursued his newfound spirituality with such gusto and energy, with such genuine curiosity, that “Dr. Dabić” was certainly more than a mere disguise. It was who he was, and why shouldn’t this kindly old gentleman, this Pinocchio pretending to be Geppetto, feel safe to eat a pancake in the middle of Belgrade?

The pancake “Radovan Karadžić” is fat and masculine: layered and filled with Nutella, cream, cranberries, nuts, and various nameless sauces. Perhaps on rare occasions Karadžić’s gluttonous self came out of hiding. Just holding it feels threatening. Heavy as a handgrenade. Nobody but a war criminal could eat that. To think that a dedicated connoisseur of meditation and macrobiotic food like Dr. Dabić would spend 150 dinars ($2.5o) to destroy his temple of the spirit strikes me as unlikely. I suspect the people at Pinocchio are lying about Karadžić’s pancake preferences, so they can charge tourists for their most expensive item.

Whatever the case, I decide to forgo the opportunity to taste Karadžić’s pancake, although the tourist agency has already paid for it. I have lost my appetite. What began in an atmosphere of irony and good-natured fun has slowly been overshadowed by something sinister. Like a snake, the Pop-art Radovan Tour has shed its pop-art skin. From a bizarre but intriguing commercial experiment, our sightseeing trip has slipped into covert propaganda, even if the organizers never intended it that way. It is just too damn difficult to find anything amusing or ironic or even theoretically redemptive in sampling the favorite dishes of someone, whose delusional and reckless policies led to the death of thousands and the displacement of more than a million, including the massacre of more than seven thousand men in Srebrenica. This is not the type of war tourism that aims to teach a historical lesson, like visiting Auschwitz or the genocide museum in Phnom Penh. To drink Karadžić’s wine and eat his pancakes smacks too much of religious ritual, a perverted form of communion in which gullible tourists are invited to partake in the body and blood of a criminal. The cuisine of Belgrade would taste sour on Sarajevo’s palate.

A quick look around tells me I’m not alone. The Serbs in our group are especially discomfited by the ordeal. For a long time their country has been stigmatized and cut off from Europe because of men like Karadžić, and Pop-art Radovan is not exactly helping to change the prevailing stereotypes. One of my travel companions, a photographer for Politika commissioned to document the tour, says, “Considering how many intellectual and cultural treasures Serbia has, it seems strange to me why people would want to take such a tour.” Like many Belgraders, he resents the continuing overexposure of Serbian wartime politicians by the Western media at the price of ignoring Serbia’s quite substantial gains in other areas. Milošević & Co. sticks like a burr to the country’s image. But try as people might to dissociate themselves from the mistakes of their old government and suppress the haunting memories of the past, the past refuses to let go. Just when everyone is thinking they are finally free to move on, Radovan Karadžić pops up in Belgrade, stealing the show once again.

Radovan Karadžić was arrested on Belgrade’s bus #73 by Serbia’s Security Intelligence Agency (BIA) on July 21, 2008. (Karadžić’s lawyer, Sveta Vujaćić, disputes the date, claiming his client was arrested earlier, on July 18, and held at an undisclosed location for three days.) He did not try to resist and quietly gave up his bus seat. The operation code-named Moskva (Moscow) had been launched several months earlier, after an anonymous tip-off. An undercover female cop posing as a patient had collected samples of Dr. Dabić’s hair for DNA analysis. (Did she bring a pair of scissors along? Did he think she wanted a relic?) After lab results confirmed the match, Dabić/Karadžić was put under round-the-clock surveillance. Every move was duly noted. Every word recorded. “I didn’t know who I was after. Had I known, I wouldn’t have taken part,” a repentant agent, who had participated in the arrest, told the Serbian tabloid Pravda (Truth).

Conspiracy theories proliferated: foreign intelligence services had spearheaded the operation; one of Karadžić’s close supporters had betrayed him and pocketed the $5 million reward; Ratko Mladić himself had ratted out his former president in exchange for immunity. There were even rumors that, to avoid widespread public unrest, the Serbian government had entered into secret negotiations with neighboring Macedonia and Montenegro to have Karadžić extradited and “accidentally” caught on their territory. When that scheme had failed, the story goes, Serbian authorities were left with no choice but to shoulder the responsibility for the arrest.

It was a responsibility long overdue. Ever since his 1995 indictment for genocide and war crimes, Karadžić had been roaming the countryside free, hiding in secluded villages and monasteries in Bosnia and Montenegro, or, not hiding, in the Serbian capital. People saw him here, people saw him there. “The hunt for Radovan” was legendary among reporters and investigators alike. In 2007 it even became the subject of a Hollywood movie, The Hunting Party, starring Richard Gere. Based on Scott Anderson’s brilliant piece of personal memoir in Esquire, it told the story of a group of journalists who were mistaken for a CIA hit team and inadvertently put on the hot trail of Bogdanović, The Fox, i.e. Karadžić. In the movie one of the main characters warns his younger companion: “Now we are headed right into the heart of this Balkan madness. It’s Serb territory, Republika Srbska. It’s a backward land where they will kill you for trying to hunt Bogdanović as easily as somebody kills a mosquito. The Fox is their God.” As hyped-up as that may sound, it holds a grain of truth: the hunt for Karadžić was an extremely dangerous enterprise that few were willing to undertake. Even NATO and the UN were leery at the prospect of a shoot-out with his notorious bodyguards. His network of associates and supporters was formidable, much too dangerous to infiltrate. Yet, why it took thirteen years to finally arrest him is an issue clouded by speculation. After his capture, he insisted there had been a secret agreement with Richard Holbrooke, the former Assistant Secretary of State under President Clinton, who had offered Karadžić amnesty if he agreed to step down from power and permanently retire from politics. Holbrooke vehemently denied those allegations, but doubts have never been dispelled.

Rumors and conspiracy theories aside, the fact remains that the young generation of pro-Western Serbian politicians, headed by President Boris Tadic, finally found the bureaucratic nerve to break with the nationalist policies of the past and seek full membership in the European Union. “May the Lord dry his seed!” screamed Nataša Jovanović, a member of the Radical Party, from the tribune of the Serbian parliament. “May the Lord’s vengeance fall on him! Tadic is the greatest traitor!” Tadic’s reforms included the appointment of 36-year-old Saša Vukadinović as the new head of BIA—the agency that had once actively shielded Serbia’s war criminals. Four days after Vukadinović took office, Karadžić was taken into custody.

Even though Dragan David Dabić did not resist his captors, his supporters would not let go of him without a fight. On the evening of July 29, fifteen thousand Karadžić’s sympathizers from all over former Yugoslavia gathered in downtown Belgrade to protest his extradition to The Hague. “Serbs were never told that they have lost,” one commentator observed. “They never came to terms with their losses.” Indeed. Die-hard backers of the old regime did not want to admit defeat, and violence soon broke out. Members of the nationalist organizations Obraz and Movement 1389 (the year of the Battle of Kosovo, a defining moment for Serbian identity) held up huge portraits of their wartime hero. Some of them were wearing Karadžić and Dabić T-shirts. “Every Serb is Radovan,” they chanted angrily, and perhaps they had a point. When Radovan Karadžić became Dragan David Dabić, he chose to lead a normal life. That was, in effect, his most perfidious move: by taking on the identity of a regular citizen he wanted to make every Serb a Radovan in disguise. Willing or unwilling, everybody had joined his private army.

Yet, Karadžić’s strategy to mobilize his fellow Serbs failed in the end. The organizers of the protest had expected a turnout of at least 100,000 people. A fraction of them showed up. The rest, it seemed, discarded the mask of nationalism to show their true faces. Marko Jevtić, a blogger for the liberal site B92, put it best: “Here I am a Serb, but I’m not Radovan, my name is Marko.”

We are reaching our final stop on the Pop-art Radovan tour. We are now in front of the Special Court. After he was arrested, Dr. Dabić was brought here, our guide tell us, and then he was sent to The Hague. From this point on, someone else will continue the story. She invites us to step out of the van and take a walk to the deserted court building. It is pitch dark outside. No one budges.

“We are done shooting,” one of the cameramen says. “We need more light.”