My photographic journey into the lives of inner city kids began by accident. The newspaper where I worked sent me to photograph a young woman, for a column called “Candid Closet.” Known for her Sunday-best dress hats, she had inherited part ownership of her family’s successful funeral business in Baltimore. During the photo shoot I was having a difficult time finding a location with good light. I backed into a large room and, turning around, found myself staring into the blank face of a thirteen-year-old black boy—dressed in an off-white suit—his tiny frame cocooned in a narrow white casket. His eyes seemed ready to pop open at any moment, as if he was surprised by his own death.

As I stood stunned by the appalling scene, the woman began to tell me about all the young people being killed and killing each other in Baltimore’s projects. She said that young people in her neighborhood had grown accustomed to seeing death’s face up close. Visiting their friends in funeral homes had become a macabre social outing—just one more party to dress up for, another occasion to wear black.

My editors were unimpressed; they said kids killing kids was nothing new. But I began to search the paper daily for stories about youths involved in shootings and stabbings. When I found obituaries, I started showing up at the funerals. Some families rejected my presence, but others welcomed me as a witness to their pain. I watched one mother, unable to cope with the loss of her twelve-year old son, throw herself headfirst into the casket, knocking the body to the floor.

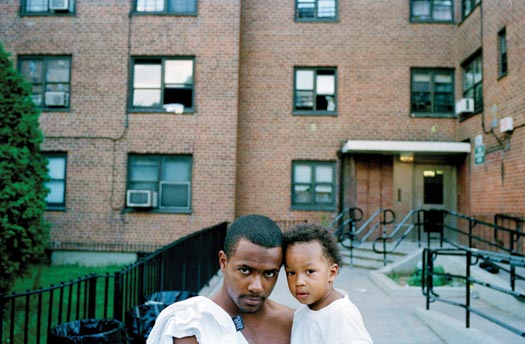

The work took me from the low-rises of Baltimore, to Chicago’s Cabrini-Green projects, Boston’s Roxbury streets, the Desire Housing projects in New Orleans, and Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant. Everywhere I saw the same dramas play out. Childhoods devoured, hope snuffed out. I saw how the harsh realities of deprivation, poverty, and racism had created a generation of lost children, whose fathers and brothers had been taken by death, incarceration, drugs, and unemployment. I spent time in countless struggling public schools. I rode along with community cops and paramedics. I met young mothers grieving the deaths of their children, passed untold hours with funeral directors. But I also visited alternative programs whose sole aim was to foster transformation and growth. I sat beside teachers, guides, healers, whose open hearts made space for young people facing innumerable challenges. In the bright moments I felt witness to the revival of promise.

I wanted to bring attention to the lives of these young people, not just to document the darkness they endure but to honor the deep strength and wisdom they possess. I also wanted to recognize the people who, from these worst possible circumstances, have found the inspiration to make their communities—and their world—a little better. Even in these most hopeless places, I found guardians of hope. Sometimes I saw miracles. I saw youth marching into the light.