How the housing crisis threatens Venezuela’s revolution

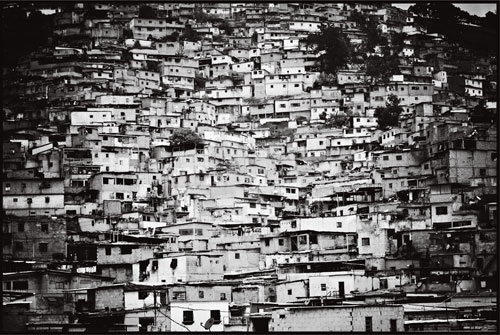

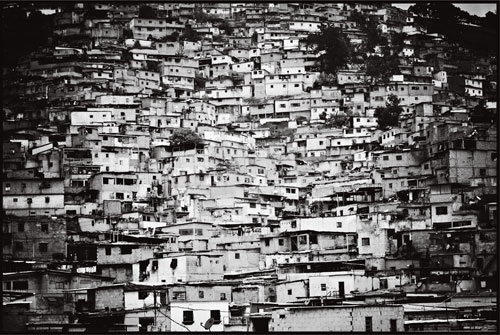

- In the last century, the city of Caracas has grown from three hundred thousand residents to more than six million—many of whom now live in dangerously unstable and crime-riddled barrios on the surrounding mountainsides.

- A tower block in the 23 de Enero building, one of the many high-rise slums in Caracas. Criminal gangs armed by President Hugo Chávez’s administration and converted into left-wing guerrillas control many of these neighborhoods. (álvaro ybarra zavala / reportage by getty)

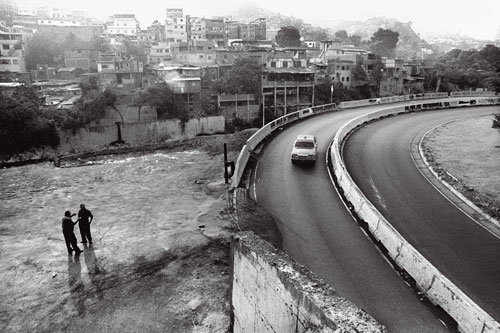

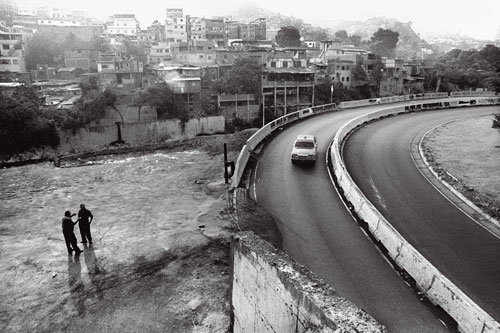

- The barrios of Caracas shadow the steep slopes of nearby mountains, climbing the walls of ravines and cresting at ridge-top roads. (andré cypriano)

- A lone figure looks down from the Confinanzas tower. At forty-four stories high, the building is among South America’s ten tallest—but it is only the skeleton of a structure and ever since a massive mudslide in 1999 has been filled entirely with displaced squatters. (michael eamonn miller)

Thirty floors above the mango salesmen and the hotdog vendors, the bustling crowds and the listless, loitering youths, a young man walks to the open ledge of the Centro Financiero Confinanzas and lights a cigarette. His sleeveless t-shirt and ragged sweatpants flutter in the wind. The sheets of glass that once framed this and every other office in the Confinanzas tower—South America’s ninth tallest skyscraper—have long since been knocked out, leaving forty-four skeletal floors exposed to the roaring chaos of Caracas. With one hand resting on the waist-high cinderblock wall he has built to keep his children from falling, the young man waves to someone on the ground below.

A chorus of car horns protests the midday traffic. The pounding Caribbean sun wilts the flowers and melts the sweets sold on the capital’s trash-strewn corners. A woman in a power suit glances up at the speck of a human, sees him waving, and turns to the businessman beside her. “What’s going on?” she asks. “Nothing,” he answers. “It’s just the invaders.”

Every day, Venezuelan newspapers across the political spectrum publish front-page articles on the most recent invasiones, the illegal occupation of property by squatters. In Caracas, invasions often begin with swift, surreptitious, and sometimes armed overnight raids. In the city’s downtown, squatters militantly occupy condemned or vacant buildings, the empty rooms suddenly packed with families. On the fringes of the city, they descend onto undeveloped land and quickly build rough cinderblock houses, their work spreading out in concentric circles around older, established neighborhoods. Some squatters even set up tents alongside filthy sewage drains or garbage heaps.

In Latin America, invasiones are not new. They are the product of forces that have haunted the continent for decades: crippling poverty, jarring inequality, and an economy broken since the “Lost Decade” of the 1980s, when Latin American countries could no longer pay off their foreign debts. But in Caracas, a city deeply divided by politics and class, the invasions have become a powerful symbol of the challenges facing President Hugo Chávez Frías. Twelve years into what Chávez has called his permanent Bolivarian Revolution, the invasiones have grown more acute and more dangerous, highlighting the government’s inability to address a basic and enormous problem: housing. Now, this national housing crisis threatens to undermine the revolution itself.

Caracas is ugly. Even lifelong caraqueños will say as much. Endless boxes of concrete and steel make a labyrinth of the downtown, occasionally interrupted by outcroppings of gleaming banks and skyscrapers. Radiating outward, the city’s neighborhoods are a patchwork quilt of rich communities and poor barrios. Concertina wire and mirrored guardhouses mark the boundaries between the two realities, but from the air, the orange brick and gray concrete of the barrios seem ready to consume the lush green of carefully manicured golf courses and lawns.

Since the early twentieth century, Caracas has grown barrio by barrio, creeping up the steep slopes of nearby mountains and down along ravines toward the sea. In 1920, there were fewer than three hundred thousand people in the city. Today, there are more than four million in Caracas’s five districts alone, with several million more—no one is quite sure how many—living in surrounding barrios.

Caracas has grown like an ever-expanding oil spill—and, in a sense, it is. Shell, the British energy company, discovered vast fields of crude petroleum in Venezuela shortly after WWI, when Europe was first coming to understand the importance of oil. By the outbreak of World War II, Caracas’s place in the global supply chain was fixed. By renegotiating contracts with European and now American oil companies, Caracas’s small political elite grew extraordinarily wealthy as millions of barrels of Venezuelan crudo flowed north to the United States.

The oil boom made Venezuela one of the richest countries in Latin America, but it also helped eviscerate its industrial and agricultural sectors and, eventually, sank the nation into foreign debt. (By 1994, foreign debt was 54 percent of GDP.) And almost none of this newfound oil wealth was reinvested in the urban infrastructure of Caracas, a city that by 1950 had become a magnet for the rural poor. The first barrios sprung up as migrant workers slaved to turn petro-dollars into highways and bridges. With the government flush with money, agriculture was abandoned, sending hundreds of thousands of rural Venezuelans to the capital looking for work. By the late 1970s and early ’80s, as Latin America’s factories went silent and its industries packed-up for Asia where labor was cheaper, Caracas had become an informal city with millions of workers but no jobs.

This rapid urbanization and skyrocketing joblessness created a severe shortage in housing. UN Habitat estimates that Venezuela currently needs 2.5 million new or repaired homes, most of them in the capital. As in Mumbai, Mexico City, Tokyo, or Johannesburg, thousands of Venezuelans sleep under bridges, plastic tarps, or cardboard lean-tos.

As you enter Caracas along the wide and notoriously dangerous highway from the airport, signs of the city’s desperation are everywhere: in the Confinanzas building’s shattered windows, in the giant, sixty-year-old housing blocks known as 23 de Enero—renowned as no-go zones for the police—and in the inauspicious title Caracas has earned for itself: murder capital of the world. The city is one of the most violent on earth. Scores of people are murdered every weekend, their bodies littering the narrow streets and alleyways of the city’s vast network of barrios. A total of 7,676 people were murdered in Caracas in 2009: an average of roughly one murder every hour.

- The skyline of Caracas is crowded with run-down highrises, like the 23 de Enero towers, many now packed with squatters. Intricate webs of power lines tap illegally into electrical service and threaten to overload the city’s power supply. (aaron sosa)

But horrific headlines tend to obscure important causes behind the problem, specifically the connections between poverty, housing, and violence—and the way the government deals with each. Under Hugo Chávez, Venezuela has become a country governed in many ways by whim. Speaking on his weekly television show ¡Alo Presidente!, Chávez doesn’t just point out the failure of the Washington Consensus—the same market-friendly, deregulatory policies that made Latin America the most unequal continent on earth and helped cause the current financial crisis in the United States—he enacts laws against it. He orders “socialist cities” built in the middle of nowhere, opens and shuts government ministries with a bark at the camera.

Only months after coming to office in 1999, Chávez pushed through a new constitution that made “dignified housing” a right of all Venezuelans. But his autocratic style hasn’t created a stable approach to the problem or built the houses the nation requires. Most housing ministers last less than a year, quickly dismissed by the mercurial comandante. According to its own statistics, the government built only 233,000 houses in its first nine years in power, compared to 344,000 houses built in the nine years before Chávez took office.

Into the space between law and reality flood the squatters. Chávez’s relationship with them is complicated and politically fraught. His critics—many of them wealthy, many of them landed—say he allows invaders to trample property rights, effectively turning the capital into a squatter city. For them, the invasions are near Biblical signs of Venezuela’s collapse under the socialist leader, a modern day tale of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Caribbean, and they serve to harden anti-Chávez anger and resolve.

- From her self-built house, erected on vacant public land, squatter Anayibe Sánchez has a view of the Valley of Caracas through the tangle of strung-up power lines and laundry hung out to dry. Sánchez is locked in a battle with government officials who characterize the squatters as invaders. (michael eamonn miller)

The invaders, on the other hand, are poor and tend to vote for the charismatic president. Some of Chávez’s most powerful constituencies live in illegal settlements. Yet, Chávez himself walks a fine line when it comes to supporting them. Soaring crime rates are often blamed on squatters, and the president has balked at giving their invasions a green light. Members of the president’s own United Socialist Party and the leading chavista newspaper have denounced the invaders as capitalists, outsiders, and thieves intent on undermining national progress. The government has even made invasions illegal, though it enforces the law irregularly.

As for the squatters, despite their fervent support for Chávez, they openly flout his authority. With each new, ramshackle house they erect, they challenge the president’s vision and his ability to lead Venezuela past its most pressing crises. In the barrios, especially recently “invaded” settlements, the revolution is being destroyed even as it is being built.

From the doorway of her house perched atop a hill in the poor suburb of Caricuao, Anayibe Sánchez can see for miles. She can see the Valley of Caracas, the makeshift power lines and sewage pipes running from her neighborhood into the streets below. And she can see the red and gray structures—just like hers—that have taken over the once verdant hills surrounding the Venezuelan capital. But even she cannot see the future of her country, though Sánchez and her neighbors are at the center of a skirmish to decide it.

Sánchez came here because, as a poor, single mother, she needed a place to live. For more than five years she has been building her home on vacant public land, breaking the law brick by brick.

She guides me up the steep and uneven staircase that runs through her small settlement like a twisted spine. “When we began, all of this land was completely vacant, totally vacant,” she says. “There was a cement block wall surrounding it, like this one here, but nothing else.” The pine trees that once covered the hill hid robbers and rapists, she tells me, as we sit down in her neighbor’s sunny kitchen, motorbikes whizzing past us on the narrow, dusty street. Now the trees are gone.

In many ways, invaders like Sánchez are the perfect foot soldiers for Chávez’s revolution; young and poor, they are a generation born into fire by the Caracazo riots of 1989, when federal troops killed more than a thousand caraqueños who were protesting President Carlos Andrés Pérez’s management of the economic crisis. The riots fundamentally changed Venezuela, destabilizing its two-party system and paving the way for Chávez’s vision of “21st-century Socialism.” Chávez was propelled into office by “Bolivarian circles,” small groups of lower-class Venezuelans who passed pamphlets and socialist ideology from hand to hand. Chávez has since worked to consolidate the revolution, pulling disparate political groups into a single party. But the invaders defy the central authority of Chávez’s administration and threaten to return the revolution to its earlier, more chaotic days.

In Sánchez’s view, the state is more an enemy than an ally. Like her neighbors, she let the mountain grasses grow tall to hide her construction from the authorities. But with each day, the threat of eviction and demolition grew. And so did the community, as more and more homeless caraqueños flocked to the hillside to clear land. They scratched roads in the dirt. They threaded pipes through the claylike earth. Soon, a neighborhood had sprung up around Sánchez’s cinderblock house. Schoolteachers and street vendors poured their meager earnings not into banks, but into their homes.

Sánchez and her neighbors named their community Los Pinos (The Pines). Today, it is home to more than three hundred people. The streets are roughly paved. Dogs bark and children scoot by on tricycles. Elaborate spider webs of power lines draw stolen electricity from the “legal” community below. Water is also stolen, siphoned off from a main. Some houses are pretty, painted bright green and yellow, shining in the afternoon sun. Most, however, are simple cinderblock cubes. Enough to raise a family in, Sánchez says. In a few houses still under construction, families cook over open fires with only the evening sky above their heads.

Sánchez’s life is an updated version of an old story in this city, in which the homeless and desperate seek a better life and a bit of land. But few legitimate jobs exist. Nearly half of all caraqueños are officially unemployed. They work on the black market without benefits and live in the tiny ranchos, or self-constructed houses, that make up the barrios. Often beginning with simple sheets of corrugated metal for walls and a plastic tarp for a roof, many ranchos blossom into three-stories of cinderblocks or brick, propped up precariously over ravines or cliffs by narrow columns of steel rebar.

The ranchos and the barrios are testaments to human ingenuity. But they can also be deadly. Invaders like Sánchez are at risk first because many ranchos are built on steep, unstable land, the only land left after a half-century of rapid urbanization. Second, because they are built on other people’s property or on parkland, demolitions and police harassment are common.

“The police come and ask, ‘Where are your papers?’” Sánchez says. “But we have to keep working in order to build our houses.” She glances around the neighborhood. “First we built that house over there, then another, then we built my house. Soon enough, people began to come together. We began to walk shoulder to shoulder against the police, against arrests.”

We relax on folding chairs and sip apple soda. Between houses, I see the steep decline to the streets below. The area where we sit was once Caracas’s largest public park. Though little remains of it, the view is still stunning, with misty mountains winding away from the city.

Despite outsmarting both police and con men who tried to push her out of her house, Sánchez now finds herself in a very different kind of battle, one that has pitted her and her fellow squatters against her downhill neighbors, chavista officials and city newspapers. Only a few days before my visit, Últimas Noticias, the most popular pro-government newspaper ran a front-page article: “New Invasion in Caricuao.”

“When it comes out in the newspaper, it’s hard for us,” Sánchez says. “All these people (down below) saying that we’ve made the place dirty. It’s a lie.”

Tensions between the invaders and legal residents living further down the hillside have begun to boil over. The neighborhood around the squatter settlement is ugly and poor but “official,” much of it privately developed in decades prior. Residents complain of aguas negras, or sewage runoff, spilling down from the Sánchez’s barrio. But the dispute goes much further. Squatters siphon off water and electricity from established communities without paying for the services. There is, in other words, a powerful economic incentive to the invasions that undermines both private property laws and Chávez’s state-run economy: why pay for utilities in public housing when you could avoid them entirely by building your own house on empty land? The result is that even middle-class professionals—including otherwise law-abiding attorneys and business owners—sometimes build a second home on invaded land as an investment.

I ask Sánchez about the common charge that the invaders are often criminals and profiteers, out to illegally “flip” the land for a profit by building a house, selling it, and leaving the new owners with fake deeds. Such flipping is part of what enrages residents in legal neighborhoods. Oftentimes, local political leaders—not always chavistas—or the mob orchestrate the invasions. And when private land is occupied, Venezuelan law requires landowners to compensate squatters for “improvements” they have made before kicking them off, adding yet another, blackmail-like incentive to invading.

“They say that people are building houses just to sell them, but I would never do that,” Sánchez says. “We built these houses ourselves, bit by bit, in order to do things ourselves. We’ve all made an agreement that those of us who invaded together wouldn’t sell our houses. None of us has moved.”

A stone’s throw downhill from Sánchez’s rancho, Hector Tovar, a government official, tries to contain his anger toward the invaders.

“I live in an apartment where I pay for water and electricity,” he says from behind his office desk. Outside his window, the hills are covered with ranchos, their unpainted walls an ugly orange in the afternoon heat. Tovar isn’t sure who the invaders are, exactly—thieves, Colombians, con artists—but he knows what they are not: revolutionaries.

“These people are professionals, professionals at building ranchos,” he says. Dressed in a t-shirt and jeans with wire-rimmed glasses, he looks no different than the invaders he is criticizing. But in Venezuela, the line between officials and outlaws, legal and illegal is anything but clear. “They come and invade here, put up a quick four columns and a roof, and make a profit. They build a house and sell it to someone. Then they invade somewhere else. They’re pure professionals, exploiting the situation.”

Professional invaders, single mothers. Somehow, the contradictions between his and Sánchez’s claims seem natural in Caracas. Reclining in his sparse office, Tovar is obviously not wealthy or connected. He is a lowly official, surrounded by controversy and corruption. He explains that the government has issued an order for the destruction of Los Pinos, but is hasn’t been carried out. He is convinced the squatters have protection from the police, from the same government for which he works. “But the problem is broader than that,” he says. “It’s systemic. The problem is that there has never been good urban planning here in Caracas.”

Chávez’s government is knotted in policy paralysis over whether to demolish invasiones or to legitimize them. The government’s inconsistent behavior is symptomatic of broader policy incoherence. When it comes to housing, the president claims to be making Herculean efforts. But experts—and the government’s own records—say very few houses are ever built. Tovar himself captures the contradictions of Venezuelan reality. One minute he insists that “this government has built more houses than in the last forty years,” but then he concedes that it hasn’t been enough.

Meanwhile, middle-class caraqueños are demanding that the government bulldoze squatters’ settlements even as squatters like Sánchez resist and apply for legal recognition of their communities through a new initiative—created by Chávez.

The president himself has vacillated for years, at times seeming to support the invaders, but recently enacting laws against them. In August 2009, using special, temporary powers that allowed him to govern by decree, Chávez passed 26 new laws, including several related to housing that ban invaders from receiving government loans and housing assistance. For people like Sánchez, the laws could cost everything.

“New invaders keep showing up,” she tells me. “And they’re putting us at risk too, under the new 26 laws. The ones coming now are really aggressive, and they don’t have rights to anything.”

She tries to draw a line between herself and the new round of invaders; she doesn’t want to risk being lumped in with them, which would make her own situation more insecure. And yet, despite his solidly anti-invasion decree, Sánchez describes Chávez in fond terms, as if he were a friend or family member.

“We’ve sent letters to the President,” she says, her dark eyes gleaming. But she grows quiet when I ask if Chávez ever writes back.

“No we haven’t heard anything from him, even though I worked on his campaign from the beginning.” She pauses. “Although you might not believe it, our intention here is really good.”

On the computer screen, a video shows hundreds of screaming men and women storming across an open field.

“Can you believe this?” says Roberto Orta Martínez. “This is when the government told them they could just have the land.” His pudgy face is clouded with disgust. Martínez is a young, wealthy lawyer in Caracas, the son and law partner of an even wealthier lawyer. The wall above his desk is covered with carefully framed diplomas. Heavy books adorn the shelves. There is a portrait of Venezuela’s Great Liberator, Simón Bolívar, and a new-age bronze sculpture of Don Quixote, lance in hand.

Martínez is busy tilting at windmills of his own. He heads the Association of Urban Building Owners (APIUR in Spanish), an organization at odds with the government and invaders over what it considers clear violations of property rights. APIUR’s initials appear in almost every one of the front-page denuncias, or “denunciations,” that appear weekly in the Caracas newspapers cataloging the latest invasions.

According to Martínez, 155 buildings remain “invaded” in downtown Caracas, all because of Hugo Chávez. “When Chávez arrived in 1999, that’s when the invasiones of empty buildings began. He took away the National Guard’s ability to kick invaders out of occupied buildings,” Martínez claims. But he also admits that many, if not most, of the buildings already stood empty when squatters arrived.

Still, Chávez deserves the blame, Martínez argues. The President has created a “politics of negligence” ensuring that “there has never been a clear and enforced policy on the invasions.” He claims that police routinely help invaders break into empty buildings, and that refashioned housing laws prevent building owners from quickly kicking them out. Now, he says, that same governmental ambivalence is allowing invaders to chop down hundreds of acres of parkland around the city and establish new barrios.

But Chávez has, in fact, stopped short of backing the invaders. When former Caracas mayor and Chávez ally Juan Barreto threatened to turn the city’s two most prestigious golf courses into public housing in 2006, the vice-president at the time, José Vicente Rangel, declared the federal government would “under no circumstances … accept that the right to property, in which it is conceived in the current Constitution, becomes vulnerable in any way.”

Like many of Chávez’s critics, Martínez believes that the president was merely allowing Barreto to do his dirty work, privately encouraging the invasions but condemning them in public. But the Urban Land Law, passed by decree in 2009, finally barred local or city governments from helping the squatters, and said future invaders would lose their right to government aid.

Whether Chávez or Barreto was to blame for the inner-city invasions, it was a series of presidential missteps that escalated the city’s housing crisis. When he first came to power, Chávez thought rent controls would solve the city’s housing shortage, but wealthy landlords responded by ceasing to rent altogether. When the president passed a law enabling renters to buy their home after living in it for a set number of years, the standoff grew worse. In 2002, with inflation soaring and housing more expensive than ever, Chávez issued a decree enabling squatters, invasores and other rancho owners to apply for legal titles. A year later, Chávez froze rental prices in Caracas, pushing inflation even higher and creating a huge housing black market. In 2003, eighty downtown buildings were invaded in a mere two months.

Soon landlords began employing private security guards to watch over their empty apartment buildings, hoping for another coup against the unruly comandante. By 2005, when the National Assembly outlawed new invasiones under pressure from APIUR and other real estate groups, Venezuela’s true revolutionary land grabs had come to an end—except on the outskirts of the city, where invaders like Sánchez are still ignoring property rights.

Today, it is these outer invasions, not the occupation of inner-city high-rises, that has become a major political talking point. But the underlying problem is the same: poor people aren’t waiting for the government to build them a house or give them land. They’re taking it. And in the eyes of middle and upper class Venezuelans, Chávez is the one letting it happen. The president may need to pay heed to their anger. In last September’s elections, his ruling party lost its supermajority in the National Assembly when opposition groups formed a coalition. Though the assembly’s power has been reduced, the election sounded an alarm. If the subject is housing, no one—right or left—seems happy.

Martínez plays another video, this one of policemen dragging squatters from a mold-stained apartment building. He admits the issue is a product of conflicting rights—those Venezuelan contradictions again—which pits property rights against the right to housing and sometimes results in blood, bruises, and broken bones.

Martínez steps out of his office for a moment and I look out his wide window at the city below. To this day, many buildings are still covered with “¡Sí!” or “¡No!” graffiti from the plebiscite Chávez won in the winter of 2004, leaving the city a palimpsest of demands and promises past.

From the ramshackle houses they have built themselves on the hillsides, it is often said that lower-class caraqueños have a better view than the rich. They look down upon the wealthy city center, where giant Pepsi and Nescafé logos stare back at them. Squatters may live in tenuous conditions, often without clean water, electricity, and sewers, but they literally occupy the high ground.

Caracas’s better-off residents feel as if they are surrounded, besieged. A fear shared by many is that if they leave on vacation, invaders will swarm into their homes—or worse, descend upon them in angry waves. After the 2002 coup against Chávez, when hundreds of thousands of chavistas filled the city center and demanded the president’s return, a peculiar rumor arose that persists to this day. It tells how wealthier Caraqueños are storing up oil, how they plan to boil it and dump it from their balconies should the poor return to the streets.

- Steel rebar bristles from the rooftops of makeshift ranchos, or self-constructed houses, in the Caricuao neighborhood. Those who live downhill complain about aguas negras, or sewage runoff, spilling down from the barrios. (michael eamonn miller)

Events in recent months have revived those fears. First a state newspaper released a study encouraging the expropriation of Caracas’s two ritziest golf courses, arguing that four thousand families could live on what are now lush greens and fairways. Then, in December, powerful floods near the capital killed dozens and left thousands homeless. The catastrophe only highlighted the existing housing crisis. In characteristically charismatic style, Chávez promptly vowed to build the displaced new houses near the Caracas airport, in the mean time renting them rooms in five-star hotels and even moving some families into the presidential palace.

When wealthy Venezuelans wondered if the victims would ever receive their new homes, or if the hotel industry was the next to be nationalized, Chávez mocked them: “You people from the upper class should have already offered your golf courses to set up tents.” Finally, in January, the president said the government would commandeer unoccupied spaces for the greater good. He then urged the poor to participate. Hours after his comments, chavistas invaded a score of sites in the wealthy Caracas neighborhood of Chacao until police expelled them. Chávez then backed off, warning supporters that “the middle class cannot be an enemy of this democratic revolution.” But with another presidential election next year and more Venezuelans in poverty than not, it’s not the middle class that Chávez is worried about.

One evening I stand alone under a streetlight on a busy corner near the invaded Confinanzas building. I am lost, unsure of where I am supposed to meet Gilberto Dan, a carpenter and a member of a local consejo comunal, or communal council, in a poor barrio in Caracas. The National Assembly created the councils in 2006, allowing communities to elect members who would then make development decisions. The councils can receive government funding for projects, and, according to one pro-government source, some twenty thousand councils have been elected across the country. It is an unusual experiment in direct democracy.

Bats and moths flit above my head as I wait. I am considering going back to my fortress of an apartment building when the phone finally rings.

“Where are you?” Dan asks, obviously aggravated. After a quick walk under one of Caracas’s elevated mega-highways, I see a portly man with glasses and white hair pacing back and forth.

Dan is friendly, but suspicious. I tell him that I want to hear about his council and about what it’s like living in such a high-risk part of the city.

“You had me worried,” he says, his caraqueño accent so strong I struggle to understand him. “I had to meet you, you see. You couldn’t come here by yourself. As a foreigner, a stranger, it would be too dangerous.”

He leads me along increasingly narrow and poorly lit streets. We cross a large intersection and suddenly the city changes around us. Concrete gives way to an unevenly paved road. To the side and far below bubbles a creek, the water a dark stain. “This is Anauco,” he says, ushering me into the barrio he calls home. An older barrio, Anauco is a maze of ranchos. While not considered invaders, many people in Anauco still do not have deeds to their houses.

We stop at what looks like a warehouse with corrugated iron sheets for a gate. As Dan opens a heavy metal lock, fierce barking erupts from within. “Don’t mind the guard dogs,” he says as we step into his workshop, but they brush so close, snapping and howling, that I have to force myself not to run. We sit upstairs. Dan passes me a paper cup of soda and some potato chips and begins describing his work on the so-called Social Project of Anauco.

“The idea is to incorporate the ten sectors of Anauco into the formal city,” he says. “There are so many projects needed to cope with the risks of living where we live.” Anauco is located at the bottom of a mountain, at the natural intersection for waters pouring off the steep slope above. The land itself is soft and prone to crumbling under the weight of hastily built houses. Three and four-story ranchos reach out over the river like Venezuelan versions of the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The whole neighborhood seems about to collapse. No one should be living here.

“The high-risk sectors of the city like Anauco are the shield that protects the formal city,” Dan tells me. In the near distance loom banking towers and office buildings. By now, about a dozen other council members have joined us in the small, white room.

- In the 1950s, the first barrios in Caracas sprung up as homes for migrants who came to the city to work on highways and bridges, constructed with newfound petro-dollars. Today, that infrastructure is over capacity and crumbling. (andré cypriano)

“We need support walls to reduce the risk of a mudslide like the one that happened in ‘99,” says a woman in her forties with dark skin, strong arms and a gap-toothed smile. Dan introduces her as Mami, and she refers to a horrific slide that destroyed much of Anauco after torrential rains swept debris off Ávila, the mountain above the settlement. On the other side of the mountain, in Vargas state, tens of thousands died as entire towns were swallowed overnight.

Mami’s house was among those destroyed in Anauco; some of her family members died.

“I saved what I could of the house, but it was difficult, with the body inside. But I built it again, by myself,” she says. “In the same spot.”

Dan, Mami, and the members of the council’s urban land committee are in charge of spending government money on small projects, like retaining walls and a radio network. But big projects have never materialized. “The problem is that there’s no political will,” a woman says. “The state has demonstrated its inability to solve the problem.”

“It’s a problem of money, of financing,” Dan says in disagreement, pointing out that the chavista mayor rebuilt a neighborhood plaza after the mudslide. “But the government doesn’t quite understand. In our case, what we need is city planning.”

“Services, we need services,” says a hefty man named Pedro Serrano. “It’s the government that has the money. There’s a debt that the city owes us.”

Finally, I ask about the invaders in the nearby Confinanzas skyscraper.

“We all know some of them. Many of them lost their homes in the mudslide,” Mami says.

“But it’s a different issue,” says Dan. He claims that some invaders are merely trying to make money by breaking into buildings or setting up squats. In Anauco, the council is just trying to rebuild its neighborhood. And rebuilding has gotten easier since Chávez introduced the consejos comunales.

“If you have a legally registered communal council and your project is feasible, the city government will give you the cash to achieve the project,” Dan says. “Say what you will about the government, Chávez has made us feel like we really exist for the first time.”

High above the din and dirt of the bustling capital, José Miguel Menéndez sits in a freshly starched shirt quietly sketching the city he loves. He speaks slowly and deliberately about Caracas in English, with the patience of a man accustomed to explaining himself to the less intelligent. On the sheet of graph paper before him, a cancerous, five-fingered tumor takes shape.

“This is Caracas,” he says.

In his seventies with slightly disheveled white hair and a neat beard, Menéndez looks more like Aristotle than an architect at the helm of Chávez’s urban revolution. Having worked and taught all over the world, he is one of a few remaining old-time leftists who has not been pushed out or distanced himself from the president.

“The story has to start with the constitution, the new constitution, because the rest is just history,” Menéndez says.

As the man in charge of writing the new housing law just after Chávez was elected, Menéndez put guaranteed housing into the constitution twice. Once as a simple “hail to the flag” under Article 82, which says, “Every person has the right to adequate, safe and comfortable, hygienic housing, with appropriate essential basic services, including a habitat such as to humanize family, neighborhood and community relations.” Menéndez also slipped housing into Article 86, on social security.

“Venezuela is the only country in the world that has housing under social security, as a basic right!” he says, laughing. But where, then, is this housing revolution?

There are signs of it, scattered around Caracas like lonely talismans amongst the smog and concrete. Earlier in the day, I visited “Las Casitas,” a new public housing community for caraqueños who had lost their houses in the ‘99 mudslides. After the slides, residents were put up in a hotel in downtown Caracas until their new homes—spacious and cool—were given to them.

But Menéndez, the head of Taller Caracas, an architectural firm in charge of designing housing solutions for the revolution, says that little has come from even the best attempts to address the housing crisis.

“Nothing has changed, revolution or no revolution,” he says wearily, suddenly sounding his age. “We still have a lot of land speculation in Caracas.” In his eyes, the housing impasse is a reflection of the uphill battle the Bolivarian Revolution has faced from the beginning: decades of hollow democracy, a country overly dependent on fickle oil money, and a capitalist elite that had no interest in redistributing wealth to the needy. It is a problem of power.

“Who decides on how space is occupied? It’s not the people, it’s the economic power, whether you live in a socialist city or capitalist city!” he says. So, Menéndez explains, in Venezuela the government is transferring power the people, allowing community councils like the one Gilberto Dan and Mami sit on to administer their own resources and solve their own problems.

Still, empowering the communal councils may only temporarily conceal the revolution’s failures. In the decade since it came into office, Chávez’s administration has largely squandered its unprecedented oil wealth, at least when it comes to spending on housing. It’s far from clear that giving money to local communities to repair things themselves—assuming the money reaches them—is the answer to a problem so large.

Thus far, even Menéndez admits that there’s no funding from the central government for a real approach to the crisis. The problem, as he sees it, is the Ministry of Housing. “It’s politics. We don’t get anything from them. The president loves (our programs), but obviously the people in the Ministry don’t love it,” he says bitterly.

Unable to successfully build formal housing for Caracas’s thousands of invaders, Chávez is trying to bring the invaders into the formal structure of the state, through the communal councils. Invasiones can effectively become official communities by establishing a communal council, a move that makes demolition or eviction much more unlikely. Even this, however, isn’t enough, Menéndez says.

“We’ve had chances,” he says. “We still have chances. The people got fed up with forty years of representation (before Chávez). They got fed up with offers not met. They got fed up with incompetence.”

He goes on: “The basic positive action of the last ten years is that everyone is politically conscious now, even above and beyond any social accomplishment.”

It remains to be seen whether the people, now so politically aware, will become fed up with the incompetence of the latest government.

We leave Menéndez’s spacious office and are soon back on the city’s endless concrete streets. Horns blare and buhoneros, or informal (often illegal) street vendors, trot past. We walk down the steep paths to a black Land Rover. Menéndez’s driver takes us across town to the Teresa Carreño Theater, where several thousand ardent members of the ruling United Socialist Party are waiting to hear Menéndez deliver a speech on the communal councils and participatory democracy. A banner reading Proposal for a New Revolutionary Institutionality hangs on stage.

Sitting next to Juan Barreto, the then-mayor, Menéndez delivers an earnest but technical speech on the consejos comunales. The crowd—a sea of red shirts, the color of chavismo—applauds wildly. For them, Menéndez is a kind of luminary. His words, and the law he helped write that established the consejos, mean everything to them. Like so much in Venezuela, the difference between a house and homelessness is a thin statute, dreamt up by one man and slipped in under auspicious circumstances. There is a palpable feeling, voiced by Chávez himself, that time is running out.

“Some might say that this is anarchy,” Menén-dez tells the crowd, many of them members of consejos within the city. “But no, we’re not anarchists. The problem is that if we are truly revolutionary, we have to proceed down an inclusive path.”

Soon Menéndez finishes, and the event concludes with a sudden shout, a revolutionary slogan filling the theater. “Socialism or Death!” the crowd cries.

Anayibe Sánchez looks small and frail, almost sickly, as she leads us back toward her house. By now the powerful Caribbean sun has begun to sink behind the mountains, sending golden light careening off the unfinished houses around us. For some Venzuelans, time, it seems, is measured in two ways: how long it takes to build a house, and how long the revolution lasts. Across the valley, small houses shimmer in the heat. Each one is painted a different pastel shade—blue, green, orange and pink—all of them the legacies of electoral promises of decades past, of reforms never delivered.

Sánchez pauses by the door to her small two-story home. “We set-up the communal council so that benefits would make their way to us,” she says. “Look, we have a problem here with the electricity. We’re stealing it, but we don’t want to. Understand? Everyone’s got to survive. It doesn’t matter if (land) is chavista-owned or opposition-owned. It’s got to produce.”

She tells me that her community will not allow any more squatters to build here; it would jeopardize their chances at government help. Plus, she says, “There’s simply no more space.”

I ask her how she feels about the way the newspapers and the Chávez government portray her and her neighbors as invaders.

“It bothers us,” she says. “It’s ugly, really ugly.”

She pauses to think. When she speaks again, she chooses her words carefully.

“People think we’re going to have extra sets of eyes or tentacles,” she says. “They call us ‘invaders’ as if we were from another planet. But we’re just occupying space that was, honestly, empty before we came. We’re from here.”