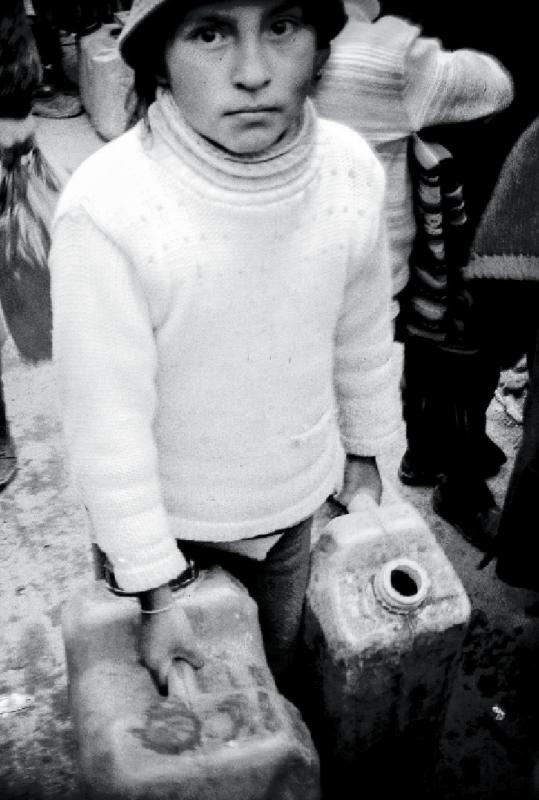

For as long as Senna can remember, she has worked to support her family. She began at four, helping prepare food that her family would hawk about town, when her father was too sick to pick rock in the gold mines. She would accompany him to market three hours away, bumping down mountain roads in a dilapidated minibus in the freezing penumbra of dawn. She’d haul bags up the slippery inclines, lug water down from the trickling glacier. To earn a few extra cents, she’d drag rocks from the maws of mine shafts, apply her tiny frame to the crushing of stones.

When she turned ten, she was hired to run one of seven public toilets that served the town’s 20,000 inhabitants. There is no sewage system in La Rinconada; no water, no paved roads, no sanitation whatsoever in that wilderness of ice, rock, and gold, perched more than 18,000 feet up in the Peruvian Andes. Senna’s job—from six in the morning to ten at night—was to hand out tiny squares of paper, take a few cents from each customer, and muck out the fecal pits at the end of the day. When she was twelve, she took a job that paid a bit more so that she could buy medicine for her dying father. Trudging the steep, fetid roads where the whorehouses and drinking establishments proliferate, she sold water trucked in from contaminated lakes.

Senna has pounded rock; she has ground it to gravel with her feet, she has teetered under heavy bags of crushed stone. But she was never lucky as a child miner; she never found even the faintest glimmer of gold. Today, with her father dead and her mother bordering on desperation, she makes fancy gelatins and sells them to men as they come and go from the mine shafts that pock the unforgiving face of Mount Ananea. When she is asked why she slogs through mud and snow for a few hours of school every day, as few children do, she says she wants to be a poet. She is fourteen years old.

Peru is booming these days. Its economy boasts one of the highest growth rates in the world. In the past six years, its annual growth has hovered between 6.2 and 9.8 percent, rivaling the colossal engines of China and India. Peru is the world’s leading producer of silver; it is one of Latin America’s most exuberant founts of gold, copper, zinc, lead, and pewter. It is an up-and-coming producer of natural gas. It harvests and sells more fish than any other country on the planet, save China.

But it is the gold rush that has gripped Peru—the search for El Dorado, that age-old fever that harks back to the time of the Inca. More than five hundred years later, it is in full frenzy again, in men’s imaginations as well as on front pages of newspapers.

In 2010, Peru extracted a total of 170 tons of gold from its mountains and rain forests, the highest production of that mineral in all of South America. Last year, it produced somewhat less. Every year has seen a drop in the output, which is hardly surprising since there is so little of this precious stuff left to dig out. “In all of history,” National Geographic reports, “only 161,000 tons of gold have been mined, barely enough to fill two Olympic-size swimming pools.” More than half of the world’s supply has been extracted in the last fifty years. Little wonder that the price of gold has soared in the past decade; little wonder that multinational companies have scrambled to wrest it from remote corners of the globe.

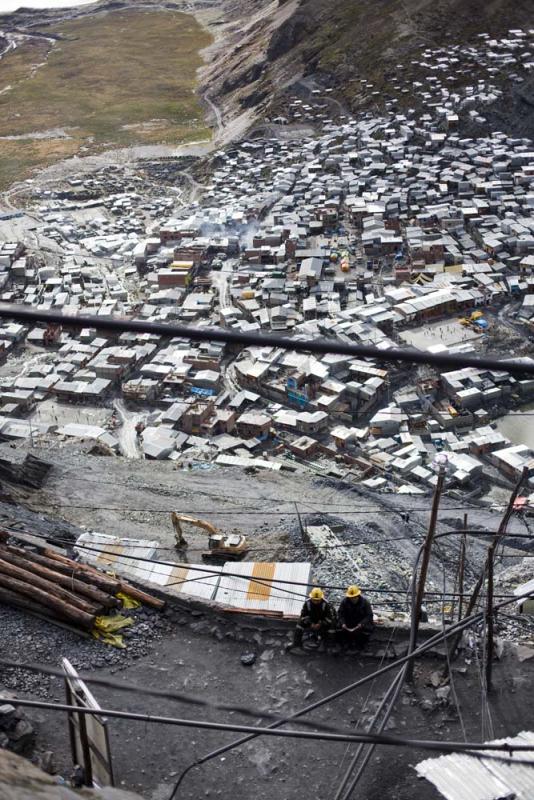

La Rinconada’s “informal” mines alone yield as much as ten tons a year—worth up to $460 million on the open market. Even illegal operations are claiming a place in the boom. The irony is that every niche of this gargantuan industry—from Tiffany’s to the mom-and-pop store—owes Osama bin Laden a debt of gratitude for its rising profits. After the sobering events of 9/11, when financial markets grew jittery and the dollar began to lose ground, gold began its meteoric upward spiral. Everyone seemed to want it, especially in the form of jewelry, and especially in countries whose populations were clawing their way up toward the middle class: India and China accounted for the highest demand for gold, their surging numbers driving the prices ever skyward. One ounce of gold, which sold for $271 on September 11, 2001, now sells for $1,700, a whopping increase of 600 percent. That boom has prompted an equivalent explosion in the population crowding into La Rinconada; it is why the number of inhabitants on that icy, forbidding rock—less than 20,000 in 2007—has doubled and tripled in the course of five years.

Today there are 30,000 miners working the frozen tunnels of Mount Ananea, most of them with families, and all in the service of a buoyant global market. There is no legal oversight, no benevolent employer, no operational government, no functioning police. At least 60,000 souls have pressed into the lawless encampment, building huts on the near vertical cant of that dizzying promontory—harboring hope that this may be the day they strike a gleaming vein, cleave open a wall to find a fist-sized nugget. They think they’ll stay only as long as it takes to find one. There are just enough stories of random fortune to keep the insanity alive.

The mines at La Rinconada are called “informal,” a euphemism for illegal, a status without which Peru’s economy would screech to a standstill. For forty years now, the Peruvian government has turned a blind eye to increasingly wretched conditions in this remote community, its government agents unwilling to scale the heights, brave the cold, take control. In the interim, what was once a region of crystalline lakes and leaping fish—replete with alpaca, vicuña, chinchilla—has become a Bosch-like world that beggars the imagination. The scrub is gone. The earth is turned. What you see instead, as you approach that distant glacier, is a lunar landscape, pitted with rust-pink lakes that reek of cyanide. The waterfowl that were once abundant in this corridor of the Andes are gone; no birds flap overhead, save an occasional vulture. The odor is overwhelming; it is the rank stench of the end of things: of burning, of rot, of human excrement. Even the glacial cold, the permafrost, the whipping wind, and driving snows cannot mask the smell. As you ascend the mountain, all about you are heaps of garbage, a choking ruin, and sylphlike figures picking idly through it. Closer in are huts of tin and stone, leaning out at seventy degree angles, and then the ever-present mud, the string of humanity streaming in and out of black holes that scar the cliffs. Along the precipitously winding road, flocks of women in wide skirts scrabble up inclines to scavenge rocks that spill from the mine shafts; the children they don’t carry in slings—the ones who are old enough to walk—shoulder bags of rock.

A miner lucky enough to find work once he reaches this mountain inferno labors in subzero temperatures, in dank, suffocating tunnels, wielding a primitive pick. In the course of that work, he risks lung disease, toxic poisoning, asphyxiation, nerve damage. He exposes himself to glacial floods, collapsing shafts, wayward dynamite, chemical leaks. The altitude alone is punishing: At 14,000 feet a human body can experience pulmonary edema, blood clots, kidney failure; at 18,000 the injuries can be more severe. To counter them, he chews wads of coca. He carries pocketfuls of the leaf to curb his hunger, prevent exhaustion. If he lives to work another day, he celebrates by drinking himself into a stupor. The ore he extracts, grinds down, leaches with mercury, then purifies in a blazing furnace will make his boss and his boss’s bosses very rich; but for the vast majority who slave in that high circle of hell, gold is as elusive as a glittering fool’s paradise.

The system of cachorreo, used by contractors in La Rinconada and elsewhere, is akin to the Mita, the system of imposed, mandatory servitude that once enslaved Indians to the Spanish crown. Under cachorreo, a worker surrenders his identity card to his employer. He labors for thirty days with no pay. On the thirty-first day, if he is lucky, he is allowed to mine the shaft for his personal profit. But he can take only what he can carry out on his back. By the time a miner struggles out under his cargo of stones, grinds it, and coaxes the glittering dust free, he may find he has precious little for his efforts. Worse still, because he must sell his gold to the ramshackle, unregulated establishments in town, it will fetch the lowest price possible. On average, a miner in La Rinconada earns $170 a month—five dollars for every day of grueling labor. On average, he has more than five mouths to feed. If he has a bad month, he will earn $30. If he does well, he will earn $1,000. In most cases, workers simply go up the hill, spend their hard-won cash on liquor and prostitutes, and count themselves lucky if they make it home without a brawl. Crime and AIDS are rampant in La Rinconada. If work doesn’t kill a man, a knife or a virus will. There are few miners here who have reached fifty.

It’s hard to imagine, as we hover over the gleaming counters of jewelry stores in Paris or New York, or even Jakarta and Mumbai, that gold can take such a hallucinatory journey, that the process remains so medieval—that little has progressed in half a millennium of human history. Families like Senna’s, who have spent as many as three generations under the spell of gold’s promise, live in abject poverty, barely able to eke out an evening meal. The world boom in the value of gold has not translated to better lives in La Rinconada. It is the same in the gold mines of Cajamarca in northern Peru (owned by the US giant, Newmont Mining Corporation), or in Puerto Maldonado, where anarchic mines carve into the Amazon jungle. In Cajamarca, which has poured $7 billion of gold into the global market in the last thirty years, 74 percent of the population live in numbing poverty. In the outlying areas of Cuzco, where Australian and US companies are busily ferreting Peru’s gold out into international markets, more than half of the population earn less than $35 a month. Peruvians, in other words, may perch on some of the world’s most valuable mountains, but as the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt is said to have observed 200 years ago, “Peru is a beggar, sitting on a bench of gold.”

Von Humboldt was quick to see—when he traveled Peru in the early 1800s—that the terrain just south of Lake Titicaca, where the Andes make a stately march south to Potosí, held vast reserves of gold and silver. According to him, Mount Ananea harbored a considerable store of wealth, even though its mines had lain dormant for a hundred years. History books tell us that during the 1700s the glacier atop Ananea had grown heavy with accumulated ice; eventually it collapsed the Spanish mines and flushed them with freezing water, drowning all life within. Spain tried to resuscitate their operation in 1803, but the land was too difficult to govern, its peaks too vertiginous, its cold too lacerating. The winds and snows of Ananea had done what the Inca could not: They had driven the conquistadors away. But, by then, Spain had scores of mines to satisfy its voracious lust for gold and silver. So it was that Ananea remained that mythic titan—remote, frigid, and threaded with gold.

Nevertheless, the myth had preceded von Humboldt, preceded conquistadors, proliferated with the Inca, and had the force of immutable truth. According to local lore, a gold block the size of a horse’s head and weighing more than 100 pounds had been found on Mount Ananea. The region’s rivers were said to be strewn with glittering nuggets. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, a half-Inca, half-Spanish chronicler who lived in the late 1500s, wrote that precisely that stretch of Peru contained gold beyond our imagining. Chunks of coruscating rock as large as a human head—and twenty-four-karat pure—had rolled from cracks in the Andean stone.

It isn’t surprising, given the attendant mythology, that a swarm of enterprising locals, toting little more than picks and hammers, would climb those reaches again. They began to come in the 1960s. Senna’s father arrived in 1980, a strapping young man with wildly ambitious dreams and legs sturdy enough to carry them. In La Rinconada, he met Leonor, a young woman who had been born there fifteen years earlier. He built a one-room house of rock, covered it with tin, and invited her to live there with him. They proceeded to have four children, of which Senna was the third. Strangely enough, that inhospitable peak was not a bad place to be during those fateful years of the ’80s and early ’90s. The Shining Path, the Maoist terrorist organization intent on capsizing Peru’s power structure, was slashing its way through the countryside, killing whole villages as it went.

This is where Senna’s story shifts, turns, like a skein waiting to ravel. In 1998, when Senna was born, Peru was, for all its rich history, an emerging chrysalis—a nation that had swung violently between democracy and dictatorship for 174 years under the rule of nearly 100 presidents. Three years later, as the country crawled out from under its long decade of civil war—when her father Juan was still a robust, fully functional miner in La Rinconada—nineteen Arab terrorists who had pledged their lives to al Qaeda flew airplanes into American landmarks and, paradoxically, Juan’s future began to brighten: The value of gold began to grow. But months later, that bullish trajectory would halt altogether for Juan. The shaft in which he was working collapsed. Just as in days of yore, when the glacier had sent torrents of water down the ancient tunnels, a plummeting mass of ice now crushed the mine’s delicate corridors and trapped the workers inside. Juan, who had been pounding a wall of stone, along with his six-year-old son, Jhon, who had been sweeping out the gravel, were caught in a sudden, airless black.

When father and son eventually clawed their way to freedom, they thanked the mountain god for their lives, but they soon found they hadn’t escaped entirely. The boy was plagued by a sickness of the spirit the Indians call susto: he ducked at the slightest sound, could hardly eat or sleep; he was deeply traumatized. Juan, on the other hand, was suffering a very manifest physical deterioration. His legs ballooned to three times their normal size. His arms grew weak. His joints ached, hands shook; he could scarcely bend his knees. Before long, he began to have seizures; and then came the constant, bone-rattling cough. He couldn’t walk more than a few yards, much less climb the path to the mine.

In the course of a fleeting moment, Juan had become a marginal citizen. He had joined the women, the children, the maimed and dispossessed—those relegated to distaff roles in a full-blooded macho society. He was too sick to do women’s work: quimbaleteo for instance, which requires one to stand on a boulder and rock back and forth, grinding ore with mercury; or pallaqueo in which a woman crawls up a cliff, scavenging for rock that spills from the mouths of mines, stuffing anything that shines into a backbreaking rucksack. Nor could he do even the simplest work: the chichiqueo, which requires a woman or child to bend over crushed gravel in standing water for hours, picking through stones in hopes of finding a gold fleck. These were impossible tasks in his condition. But he had to do something: there were bills to pay, mouths to feed. In time, he decided to cook for a living. Hunched over an ethyl-alcohol burner on the bare earth of his hut, he produced pot after pot of soups, spaghettis, stews, and sent his family out into the streets to sell them. At night, he drank whatever alcohol was left, to dull the pain of humiliation.

The labors of Juan’s children, which until then had been sporadic and secondary, now became indispensable, primary. His wife, Leonor, and eldest daughter, Mariluz, dedicated themselves to the pallaqueo, scaling escarpments with hundreds of women who worked their way up like an army of ants. It is brutal, exhausting work and, in it, a body suffers a pounding battery—no less from the weight of rocks than from the relentless cold, which can dip to -4 degrees Fahrenheit. The women of La Rinconada are old by the time they are twenty. Chances are they have lost their teeth. Before girlhood is out, their faces are cooked by sun, parched by wind; their hands have turned the color of cured meat; their fingers are humped and gnarled. You can feel the toll of the pallaqueo when you see Senna look up and cringe at the bright, blue sky. She squints at a camera flash, shades her eyes. Her black eyes have turned a milky gray.

According to the United Nations, more than 18 million children between ten and fourteen are engaged in hard labor in Latin America. Most are “informal” workers like Senna—underpaid, overworked, and grossly undercounted. More than 2 million are in Peru, which accounts for the highest ratio of child laborers in all of Latin America. To put it more plainly: one out of every fourth Peruvian child works regularly, and does so in physically dangerous conditions. Perhaps because of ignorance, certainly because of necessity, parents whose children work alongside them in La Rinconada find nothing wrong with this practice. They are repeating an age-old cycle. Their children accompany them to work just as they once accompanied their parents. When a young mother enters a mine with a baby strapped to her back, she does not know that the dynamite fumes and chemical vapors can do lasting damage to her infant’s brain; ditto for the mother whose child pours mercury into the mix while she grinds away on the quimbaleteo; ditto for the father who wades into a cyanide pond side by side with his son. No government official has come around to explain the longterm effects: blindness, brain damage, nerve damage, lung disease, lumbar deterioration, intestinal failure, early death. According to the Institute of Health and Work in Peru, more than 70 percent of all children and adolescents in La Rinconada suffer chronic malnutrition; as many as 95 percent exhibit some form of nervous impairment. But even if parents of these children were lined up and given this tragic news, they might have no choice but to keep them working anyway. How else could they afford to eat? How else to keep warm? How else to buy the tools to work another day?

Aware that to tamper with this fragile system of survival would be to undermine the poor population’s ability to subsist, the Peruvian government has been slow to outlaw child labor. Peru was one of the last Latin American countries to ratify the United Nations Convention that prohibited children under the age of fourteen from working (ILO/UN #138). Even so, although Peru finally signed that document in May 2001, the mining boom that immediately followed made it difficult to enforce the law. To do so would mean Peru would have to pull 50,000 children from the nation’s work force. And that is a very hard thing to do when business is booming and a country’s growth rate is among the highest in the world.

Few places expose the dark side of the global economy more starkly than the lawless twenty-five-acre cesspool of La Rinconada. For every gold ring that goes out into the world, 250 tons of rock must move, a toxic pound of mercury will spill into the environment, and countless lives—biological and botanical—will struggle with the consequences. It doesn’t take a social scientist or a chemist to walk through that wasteland and reckon the costs.

For a girl like Senna, there is a further danger, very different from the toxins, vectors, and violence that plague her town. La Rinconada is a humming beehive of brothels, looking for girls precisely her age. A lawyer and social worker, Leon Quispe, who has dedicated himself to the welfare of the community, estimates that anywhere from 5,000 to 8,000 girls, some as young as fourteen, move through La Rinconada’s cantinas in any given year. They are held captive as sexual slaves. Some come from as far away as the slums of Lima, but most hail from little villages around Puno and Cuzco—a sad cavalcade of gullible girls who arrive in La Rinconada believing they will wait on tables, sell food, and earn good tips; that they’ll be able to send their destitute families some measure of stable income. In their enthusiasm, they hand over their identity cards to a sweet-talking recruiter. What they learn when they arrive is that it isn’t food they will be selling. Their bodies will be the commodities, and the prices have been long established: Sex with a bargirl costs a man a few drinks and a few extra soles; a young girl’s hymen is worth a seed of gold.

La Republica, one of Peru’s major newspapers, explained the racket via a single story: Two sixteen-year-old girls from a tiny village outside Cuzco were approached in a public park by a woman they knew, a former neighbor. She offered them $500 a month to work at a restaurant in the airport city of Juliaca—all benefits included. Since they were virtually penniless, they readily agreed. But the only time the girls spent in Juliaca was the time it took to change buses. Four hours later, they were in a dilapidated bar in La Rinconada, in time for the miners’ change of shifts. It was then that they learned they were obliged to consort with men, offer them sex. They were told the rules: If a man touched their breasts or genitals, they were not to rebuff them. They would be given a ticket for every six bottles of beer their clients consumed. One ticket was worth four Peruvian soles, or $1.25. Whatever sex they might negotiate would be traded at a more favorable rate: the proprietor would only take half. The girls quickly found that they had no way to exit that nightmare: they had no papers, no means to travel; and a surly guard with a knife was at the door.

The cantinas in La Rinconada are twenty-four-hour-a-day operations. They do business out of slipshod edifices that climb up the road willy-nilly, alongside the gold-burning shops. During the day, miners come for a beer or to have their mercury-laden nuggets fired down to pure gold. The crude furnaces sit out where everyone can see them, spewing mercury into the open air; the fumes snake through the cantinas and float out onto the glacial snow, La Rinconada’s primary water source. Mercury levels in those public spaces are 5,000 percent higher than what is permissible in regulated factories. But here, no one is measuring. Women and children hurry through the murky haze, hawking their food and water. The sick struggle in and out of doorways, breathing the deadly air. At night, when the drinking establishments turn into brothels, La Rinconada descends through every circle of hell. A deafening music pounds; drunks reel through the open sewage; food vendors traipse through the phantasmagoria as if it were a happy carnival, and small children flit past, laughing and falling into the toxic mud. Downstairs in the brothels, the young girls are lined up against the walls, their faces resolute and grim. Upstairs, by the light of a thousand flickering strobes, sex is traded, violence runs riot, and buckets of urine are tossed from windows as the poor drink away their hard-won gold.

It isn’t a pretty picture. But so famous has La Rinconada become for its wanton nightlife that village boys for miles around come to work in the mines, have sex with women, and drink all the beer they can. A schoolteacher from Puno explained that often the boys are never the same after their journey to the frozen mountain: They drop out, leave home, and go on to a life of profligacy and ruin.

A life of profligacy and ruin was precisely what Juan Ochochoque did not want for his children. He had worked all his life to feed them, house them, give them what he could. Although he was illiterate—although he had never stepped foot inside a school—he began to counsel Senna, who was all of five when they began to cook together over their tiny ethyl stove, that education was her only way out of the grind of poverty. How he knew it is anyone’s guess. There was nothing in Juan Ochochoque’s past to suggest he would value an education, except for a vague perception he seemed to have about the prevailing power structure: The engineers who ran La Rinconada read and wrote; they knew mathematics, physics. A hierarchy was at work, and it involved knowledge and intelligence. He wanted his children to have that advantage. His wife, Leonor, did not necessarily agree. As far as she was concerned, the family needed to make ends meet, and that meant immediate results—not the sort of long-term, hard-won investment that education entailed.

By the time Senna was ten, her father was dead. His bloated body—shot through with chemical toxicity—had reached crisis point as he left a bus at the foot of Mount Ananea, trying desperately to find a cure. It gave out suddenly as Leonor helped him to struggle across the road. Juan Ochochoque’s long battle with La Rinconada’s poisons was over, but the lesson he left his daughter refused to die: It was he who had pointed out, as his little girl puttered about alongside him, telling him stories, making up ditties, that she was good at words, good at digging out the right ones, good at polishing them to a fine shine; she was a miner of a different kind.

Which brings me to the crux of this story.

I had gone to La Rinconada precisely because of Senna’s words. I had seen a video of her telling the story of her father’s illness and the wreckage it had left behind. Throughout her story, she summoned allusions to the heartbreaking poetry of Cesar Vallejo, using his words to express what she felt. I had never heard, in all my years sitting at dinner tables with the Lima elite, such easy familiarity with Vallejo’s poems. I had been charged by a film company, the Documentary Group, with the task of finding a Peruvian girl in a poor community: a child whose story might be documented by the award-winning American director Richard Robbins in a movie about poverty around the world. His advance film party had shot videos of young girls in the Amazon jungle, of girls in the icy reaches of La Rinconada and Cerro Lunar. Senna was not particularly photogenic. She was shy in front of the camera. Hunched and incommunicative, she didn’t seem like a good candidate for a feature film. But when she started to speak, when she pulled Vallejo’s words from the air to describe her pain—“There are blows in life, so powerful”—a flame seemed to grow within her. I was riveted. “Blows like God’s fury—like a riptide of human suffering rammed into a single soul … I don’t know.”

Social science now tells us that if we can take indigent girls between the ages of ten and fourteen and give them a basic education, we can change the fabric of an entire community. If we can capture them in that fleeting window, great social advances can be achieved. Give enough young girls an education and per capita income will go up; infant mortality will go down; the rate of economic growth will increase; the rate of HIV/AIDS infection will fall. Child marriages will be less common; child labor, too. Better farming practices will be put into place, which means better nutrition will follow, and overall family health in that community will climb. Educated girls, as former World Bank official Barbara Herz has written, tend to insist that their children be educated. And, when a nation has smaller, healthier, better educated families, economic productivity shoots up, environmental pressures ease, and everyone is better off. As Lawrence Summers, a former Harvard University president, put it: “Educating girls may be the single highest return investment available in the developing world.” Why is that? Well, you can make all the interpretations you like; you can posit the gendered arguments; but the numbers do not lie.

The irony in all this is that young girls like Senna are hardly valued in La Rinconada. The girls and women of that harsh, remote mining town may well be the community’s most promising resource, but the overwhelmingly male culture of the mountain leaves little choice for a young adolescent female but to follow her mother to the cliff and perpetuate a cycle of ignorance and poverty.

All the same, there are signs that the overall business of gold mining in Peru may be facing significant corrections. In 2006, residents of villages near the largest gold-mining operation in all of South America, the US-owned Newmont Mining Corporation’s Yanacocha Project, just outside the historic city of Cajamarca, blocked the roads and declared that they had had enough of the company’s toxic and predatory practices. A bloody stand-off between the mine’s armed security forces and the residents of Cajamarca followed. Five protesters were killed. By the end of 2011, the mine workers were radicalized; they called a strike against Newmont’s new Minas Conga Project. Their complaints were loud and clear: The workers were operating in wretched conditions, the environment was being ravaged, the toxicity of chemical waste was proving ruinous to public health.

Indeed a German scientist claims that the once sparkling lakes that surround Cajamarca are dangerously tainted and the 2 million residents of that city are at risk. But there is more than environmental despoliation at issue here: Once Peruvian ore is excavated, processed, and the gold shipped abroad, Peru retains a mere 15 percent of Newmont’s annual $3 to 4 billion profits. The protesters and strikers in Cajamarca became so outraged about such injustices that troops in riot gear were called out to contain what was perceived as a larger threat to the Peruvian economy. On July 4, a priest who was an outspoken leader of the protest movement was taken by force from a bench in a public park, arrested, and roughed up before he was let go. President Ollanta Humala, who had won the presidency on a socialist vote, now said with unequivocal free-market conviction that Conga would continue to mine, albeit with stricter government oversight. Peru’s boom, in other words, is sacrosanct. Gold trumps water; and world markets take precedence over people.

In June of this year, La Rinconada followed Cajamarca’s suit. Although La Rinconada is an “informal” operation with no one but Peruvians to blame for its troubles, workers emptied the mines, shut down the schools, and put down a collective foot: They called for the Peruvian government to give them water, a sanitation system, paved roads, health clinics, heightened security, child care, a better school, and all the attendant benefits a producing economic sector deserves. The nonprofit organization CARE is willing to help ameliorate the situation and, after having abandoned La Rinconada as hopeless some years ago, has sent representatives up the mountain again. In April, the head of CARE Peru, Milo Stanojevich, made the difficult trip to see the evidence for himself. But it’s a risky business. The inhabitants of La Rinconada are all too aware of the proverbial “Beware of what you wish for.” With government gifts come government regulations, and that means federal taxes, the marginalization of cachorreo workers, and the very real possibility that the work from which women and children now make a subsistence living—the sweeping, the pallaqueo, the chichiqueo—will be outlawed.

To Senna, the strikes in La Rinconada, which continue even as I write, have meant something more potentially harmful: School, in which she has invested all hope for a brighter future—which she had promised her dying father she would attend—has been shuttered, its doors bolted. The teachers in La Rinconada, after all, are miners who work there for extra cash; so school, for better or worse, is tied intimately to the mines. Even in this, even in education, a child’s life is contaminated by gold’s offal. But it’s not the first time Senna has faced adversity. One gets the feeling that the seed of survival, planted so carefully by her father, will take root and flourish anyway. If a girl is motivated enough to save her hard-earned pennies, buy a dog-eared pamphlet of poetry from her teacher, and memorize whole pages of verse, that girl stands poised to redirect her future, make Herculean changes—a woman warrior, indeed. She will learn; she will open that door to a better world. And, if the social scientists are right, a whole village will follow.