The Orbit

I can’t tell you his name because he—a paperless migrant from Honduras living in Guatemala, ferrying people, corn, and the occasional load of drugs back and forth on a homemade boat—asked me not to. But I can tell you this: His name resembles that of a planet. He lived in Texas for a year and a half, worked in roofing, but an immigration raid deported him back to Honduras. He’s headed back north again, his thirteenth try, but for now he’s biding his time in Guatemala so he can earn a few bucks a day aboard these rafts—salvaged wood atop old tractor tires. Why does he keep returning to the States? “You can’t make a living where I live,” he tells me. “Everyone knows that.”

A trans woman from El Salvador had warned me about the river earlier that morning. “It’s crazy down there. Zetas, narcos, gangsters, police, migrants, addicts—everyone. Be careful by the river.” But this guy just wants to give us a ride and take our rumpled bills. He immerses himself in the water to cool off, then poles us toward Guatemala, hair still dripping. The current catches us and drags us east toward the mountains of Chiapas, where the crossing gets more tricky. Here it’s easy enough—just hop a vessel and you’re on the other side in moments, just under the nose of la migra, who, to protect commerce, ignore this sort of back and forth. What’s hard is getting farther north, he explains, past the checkpoints, the deserts, the gangsters. But our captain? He’ll pole back and forth between these two countries that aren’t his until he has enough cash to try for the States. And if he’s sent back he’ll try again, orbiting these middle lands until he makes it.

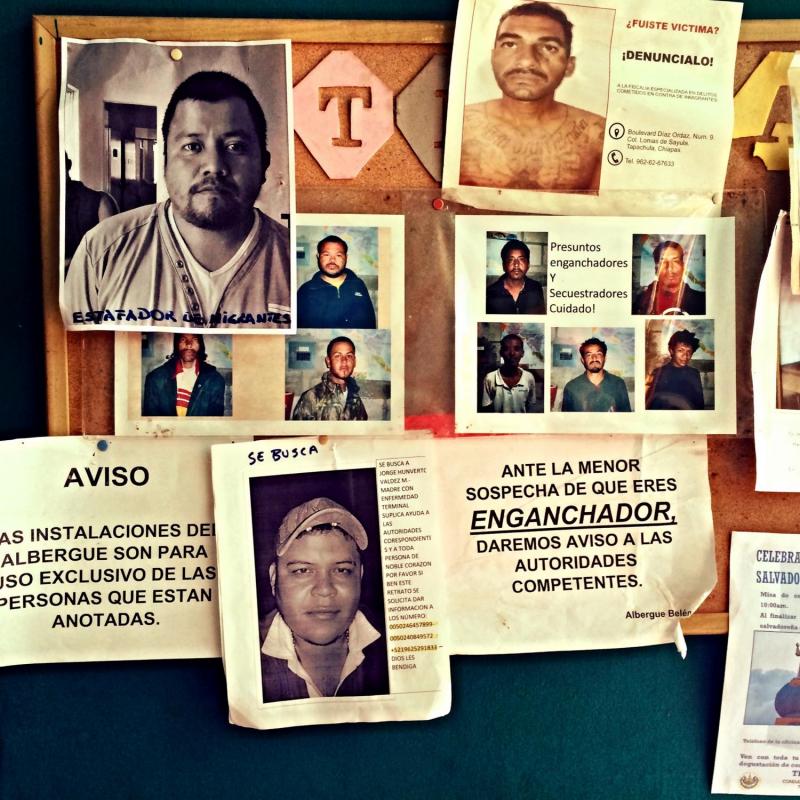

Bulletin Board

There are the people the migrants know to be afraid of—the police, Border Patrol, the tattooed gangsters. Then there are the incognito migration profiteers. They pretend to be coyotes, human smugglers. Or they hide in the bushes in order to raid and rob and rape migrants passing quietly by. Now that Mexico has leveraged US dollars to crack down on migration, explain the staff at the migrant shelters that string north like an underground railroad, those bound for the States are being pushed toward routes where they’re at greater risk of exploitation.

This particular bulletin board is in the Belén shelter, one of the southernmost in Mexico. The day before yesterday, three sets of parents arrived from El Salvador, fleeing gangs. They’re headed for Baja California where they know a guy who can get them jobs. Tomorrow, along with another Salvadoran couple and their eight-year-old daughter, they’ll hit the road early—first on buses; then, when a checkpoint comes into view, they’ll offload and head for the hills. “You never know what can happen off the road,” one woman told me, motioning to the bulletin board. She was sorting her belongings into piles: things to bring and things to mail to Baja. A sweater and clean pants went into the “keep” pile; a brand new satin bra, tags still on, and a jar of beans (too heavy) were tossed in the pile to send. She placed a jar of cream on top of the “keep” pile—foot balm to soothe the cracks and blisters. “It’s going to be a lot of walking,” the eight-year-old told me, “but I’m really strong.” She snatched up the foot cream, removed her shoes, and began massaging the soft pads of her feet.

Twenty-First Century

“These days, they really don’t get that far north,” a staff member from San Salvador’s deportee reception center told me. Deportations to El Salvador used to come from the US, but now they come from Mexico—in June, 1,900 from the US, 3,000 from Mexico, most on overnight buses.

This is the Siglo XXI detention center in Tapachula, Mexico, a complex surrounded by high walls and shrouded in secrecy. At any given time thousands of down-on-their-luck migrants from El Salvador and elsewhere are locked up thanks to the country’s recent immigration crackdown. Just down the road is a private charter-bus company where, on a hot day in August, a handful of Pullman coaches were idled and parked. The conductors mopped the floors of some and tinkered under the carriages of others, preparing for the night’s run. Several times a week, they load up a few dozen buses, about fifty people each, and head south across the Mexican border and into Central America to deposit the failed immigrants back home. Part of Mexico’s Plan Frontera Sur, an operation to secure its southern border against drugs and immigrants, Siglo XXI—or “Twenty-First Century”—is doing the dirty work for the US: If you can stop them in Southern Mexico and deport them from there, they won’t make it to the Land of the Free.

The day I visited the San Salvador returnee center, three buses arrived from Siglo XXI, carrying more than 170 people. Another three bus loads arrived shortly thereafter from a detention center farther north. The failed immigrants disembarked the buses looking haggard and weary, picking up their belongings that were tossed from the cargo hold onto the sidewalk: backpacks, dusty duffel bags, plastic sacks tied in double knots. The migration emergency in El Salvador, explained the head of the returnee center, “is not going to stop.” These very same Pullman buses would be back the following week.

This essay is part of our #VQRTrueStory project, a social-media experiment in nonfiction that delivers stories across platforms. Each week, a contributor takes over our Instagram feed, @vqreview, to post original dispatches that tell the stories behind the pictures. The dispatches are then published on our website, and two are selected for inclusion in each issue of the magazine. You can visit the #VQRTrueStory archive to read all the contributions so far. And be sure to follow @vqreview to keep up with the project as it unfolds.

Reporting for this project was made possible by a French-American Foundation Immigration Journalism Fellowship.