By the time the train approached the station, night had fallen. Sarah Wilcox gathered her bags and descended the stairs to the luggage rack. Her husband, Ethan Hughes, helped slide an unwieldy cardboard box toward the door. The steel floor rocked beneath her shoes. The conductor’s voice crackled over the loudspeaker: “This is not a smoking stop, folks. Unless this is your final destination, please stay on board the train. The next smoking stop will be Kansas City.” Sarah peered out the window but saw only her reflection. She turned to the woman beside her.

“Are you from here?”

The woman said she was.

“Can you see the stars here?”

“Oh, yes,” said the woman. “They’re beautiful.”

Sarah and Ethan had spent two nights on the train. First they rode the Silver Meteor from Fort Lauderdale to Washington, DC—a twenty-two-hour haul. Then eighteen hours to Chicago aboard the Capitol Limited. Had she sifted through newspapers discarded by fellow passengers, Sarah might have seen an item concerning the bankruptcy of the nation’s second-largest subprime mortgage lender, the most recent in a string of nearly fifty such failures. Or that a senator named Barack Obama had announced a bid for the presidency. Steve Jobs had unveiled a device called the iPhone, its failure quickly forecast: Nothing more than a luxury bauble that will appeal to a few gadget freaks. She had slept some, lulled by the clicking of the rails and the muffled whump each time a bridge flexed beneath the car.

She was hungry. During these final five hours, aboard the Southwest Chief, she had eaten the last of the peanut butter from Florida.The train had smelled of disinfectant when it left Chicago, but as the passengers began to snore beneath blankets, sprawled in their seats, the air had thickened and gone stale. Through Illinois, Sarah had gazed down at backyards and country lanes, but once the sun had set, the window allowed no glimpses of her new home. She was as giddy as a bride.

The train shuddered to a stop, and the conductor slid open the steel door and placed a set of portable yellow stairs on the platform. An icy wind nipped Sarah’s ears as she stepped into the white pool of light. Sarah and Ethan wrestled the cardboard box off the train, piled it with the rest of their belongings. The train whistled and chugged into the night. The smattering of departing passengers was whisked away by waiting cars. The frozen air smelled of wet wood.

Sarah cut open the box with a pocketknife. Inside were bicycle parts. Resting a frame upside down on the concrete, she attached the wheels and brake cables. Her breath hovering in clouds, she flipped the bike and threaded the seat post into its orifice and tightened the clamp. By the time both bikes were ready, the station was empty. Fingers of trees stretched toward the dark sky. The whole place could be swallowed by the night. They hung panniers and fastened backpacks to the racks. Sarah zipped her jacket, snugged a wool stocking cap beneath her helmet, inserted her hands into warm gloves.

After studying a folded photocopy of a map under the lamps of the platform, Sarah and Ethan crossed the tracks and pedaled into town. They glided between the plain white clapboard cottages, a distant streetlight shimmering in a halo of mist. Sarah felt awkward, as if she had misassembled her bike. With each pump her knees bumped against her belly. But it was not her bicycle that had changed. It was her body. She was in her fifth month.

Three months earlier, she and Ethan had compiled a list of twenty criteria for a home, a place to begin their family. Among other things, they intended to grow as much of their own food as was possible, so they listed: year-round drinking-water source; long growing season with ample rainfall.

Those requirements alone had eliminated huge swaths of the country: the northern plains were too wintry, the Southwest too dry.

Another goal was to live without electricity and petroleum. That did not mean they would generate power with solar panels or wind turbines. They simply would not have it: no hot-water heater, refrigerator, furnace, washing machine, computer, or cell phone. No lightbulbs. They added to the list: existing structures not wired for electricity; no building codes, to allow building with natural materials.

Sarah and Ethan would not use cars or airplanes. They would rely on walking, bikes, and public transportation. They wanted to be: fewer than five miles from a train station; within biking distance of a college town.

They also listed criteria of purely personal preference. Sarah was a classically trained soprano and wanted a town where she could sing opera. As for Ethan, a former marine biologist raised in a Massachusetts fishing town, he hoped to be near the sea.

Ethan and Sarah already knew of a place that met most of their criteria: the forested hills of Cottage Grove, Oregon, where they had rented a homestead for five years and Sarah had sung in the chorus of Carmen. A generation ago, they probably would have bought the thirty-acre compound of forest and garden, with its long summer days and cool, dry nights. But back‑to‑the-land havens in Oregon and California and Vermont had long since been discovered. The property would have cost half a million dollars. And so one essential criterion effectively precluded ocean and opera: affordable land.

Their pickings were slim: the parts of America without national parks and bike paths and natural food stores. Ethan had cycled across the United States and not found Missouri to his liking—flat and buggy and landlocked, humid summers and bitter winters.

Alas, Missouri it was. A friend found an eighty-acre Amish farm for sale: a hundred-year-old bungalow, barn, shop, two ponds, a hardwood forest, plenty of pasture and fertile soil. Devoid of tide pools and bel canto, the sparsely populated northeastern corner of Missouri, shoehorned between Iowa and Illinois, nailed the other eighteen criteria. And the bubble of land speculation had not reached it. Ethan and Sarah paid $160,000 cash, sight unseen, for the house, barn, and all eighty acres.

Which is how they had come to arrive on an April night in La Plata, Missouri, population 1,467, a once prosperous trading post along the Santa Fe Railway, now fallen on hard times. They cycled through the town square, doorways dark, wind rattling the leafless trees. The upstairs windows of the storefronts were boarded with plywood and corrugated fiberglass. Tacked to the door of an auction house was a list of farm implements and an inventory of tools and appliances with a brief preamble: As I am residing in a nursing home will sell the following items. In the window of one of the few functioning enterprises, the Christian Ministries Clothing Center, was taped a terse hand-scrawled note: no tv’s.

Sarah did not share her husband’s aversion to the Midwest. Although born and raised a city girl in Houston—singing at a performing-arts school, speeding over freeways to coffee shops, working out at the gym—Sarah came from deep Iowa stock. Her parents were born there. Her great-grandparents had been farmers, and their parents homesteaders, just like in Little House on the Prairie. Sarah had graduated from Grinnell College, 150 miles north of here. Moving to Missouri felt like coming home.

The beam of her headlamp projected a meager saucer of gray on the asphalt. After a series of left-hand turns, the couple had to admit they were lost. They pedaled toward a glimmer, which materialized into a gas station bathed in neon along a highway. A police cruiser idled out front. They went inside to ask directions and the officer told them that all they needed to do was cross the highway to a gravel road named Mockingbird Hill. They mounted their bikes and inched to the shoulder. But Sarah could see no outlet on the far side of the four lanes. A truck roared past, rattling her teeth.

“I don’t see where we’re supposed to go,” she said.

Just then the red lights of the cruiser flashed behind them. The officer crawled forward, the big engine purring, and Sarah saw him smile from the open window.

“Follow me,” he said.

He escorted them across four lanes to where, sure enough, a gravel road descended from the embankment past a graveyard and into farmland. Keeping a respectful distance in front, he chaperoned them through rolling hills and fields. Sarah rode in silence, sucking in the cold air, trying to keep up, scanning each hill for the house she had seen only in pictures. It was like a treasure hunt. The frozen road beneath her tires was as smooth as clay. Lit by starlight, the dark earth of unplanted cornfields was milky with frost. A dog ran snarling from a farmhouse but left them alone.

It was an odd parade: a crawling police car, lights ablaze, and a man and his pregnant wife pedaling bicycles across the winter prairie. This was not the way they’d expected to begin their new carless, electricity-free life. Sarah looked at Ethan, and without warning laughter erupted. Not a rising giggle or a modest chuckle, but an instantaneous wail, a one-note aria, the kind of laugh that startles animals and delights children and causes stage actors to flub their lines—her laughter rang in the night.

Fifteen minutes later Mockingbird Hill teed against a paved road whose sign said simply “E.” The deputy waved them close to the window, pointing. “It’s just a few miles out that way,” he said. At the first intersection they should take a left and they’d be there. With that he gunned it back toward town. Sarah and Ethan rode on into the night, rising and falling through the contours of the countryside, stars lighting the way.

In most discussions about technology, Luddite is a dirty word. Even the most committed activists embrace cars, planes, and computers as a means of furthering their cause, and begin their criticism of some specific innovation—fracking, pesticides, genetically modified organisms—by clarifying, “I’m not a Luddite, but…”

Not so at the Possibility Alliance (PA), which had virtually excised itself from the industrial system of food, fuel, and finance. Ethan delivered the most coherent critique of technology I had heard. I was reminded that the original Luddites, the nineteenth-century weavers who smashed industrial looms, were not mere hicks who couldn’t comprehend scientific advances, but rather principled resisters who correctly predicted that industrialism would end their trade and their economic independence.

At a picnic table in the shade of a walnut tree, Ethan proposed that we divide technologies into three types. First were those that required no industrial inputs. Dating back long before the industrial revolution, these included walking, horseback riding, knitting, weaving, candle making, hunting with spears and bows and arrows, and cooking over a fire. The next level included those technologies that required a one-time industrial input for their manufacture but afterward were powered by nonindustrial inputs. These included saws, hammers, bicycles, plows, and woodstoves. The last were those that required the constant industrial inputs of oil, coal, and electricity. In America, virtually everything we use falls into this category: lightbulbs, stoves and furnaces, internal combustion engines from chainsaws to lawn mowers to cars to tractors, electrical devices from cordless drills to clothes dryers to computers to cell phones. Ethan’s goal was to use as much as possible of the first category, plenty from the second, and none from the third.

The result was that the PA had adopted much of the technology of the nineteenth-century American pioneers. Most of the food its members ate—and fed to their thousands of guests—was grown without tractors, petrol, or chemicals. In four large gardens they cultivated squash, tomatoes, beans, greens, cabbage, peppers, and a dozen other edibles. Pears and apples ripened in the orchard. They harvested herbs for tea, spices, and salves. They foraged in the forest for mushrooms and berries. Twice a day they milked goats and a cow, producing ample cream, cheese, and yogurt. A hutch squawking with dozens of chickens provided eggs and meat. They kept bees for honey and grew sorghum as a sweetener. They hunted deer and wild turkey, and fished the ponds for largemouth bass and bluegill and catfish.

With a pair of draft horses they plowed and planted wheat. One morning we threshed the wheat by hand, slapping it against the wall of the barn and collecting the berries in a tarp. Then we ground it to flour in a mill powered by a stationary bicycle. That night we baked challah in an outdoor wood-fired oven.

With Missouri’s ample rainfall, the crops did not require major irrigation. The PA bought its drinking water from the county system, a dependency it was working to eliminate. In rooftop cisterns they collected rain for washing dishes and clothing. A gravity-fed filter purified some rainwater for drinking.

They supplemented their own crops with other local food. In the autumn they picked apples by the bushel at a nearby orchard. Their neighbor who bred cattle gave them beef when he culled the herd.

Lacking refrigeration, members of the Possibility Alliance ate what was fresh and in season and stored the rest. Apples, potatoes, beets, and squash wintered in the cellar. They canned hundreds of jars of tomatoes and string beans, and fermented crocks of sauerkraut. If they received more beef than they needed, they canned the remainder.

Items not available locally they ordered in bulk: vegetable oil, salt, oats, and flour. They insisted on purchasing rice from Texas instead of California. In an era of easy access to a range of upscale produce year-round, when nobody blinks at apples from New Zealand, avocados from Israel, and coconuts from Thailand, I tasted an actual locavore diet. At the Possibility Alliance there was no sugar, coffee, black tea, wine, chocolate, bananas, avocados, coconut milk, or peanut butter.

I asked Ethan if he missed any of those foods. “Coconuts,” he said. “But I’m not going to eat them.” One time, he remembered, some friends had arrived on the train from Los Angeles harboring a sack of California avocados, of which he had savored each bite. The resulting meals ranged from the grim to the exquisite. Some breakfasts consisted of cold-soaked oats and pick-your-own Concord grapes. Other mornings the cook scrambled eggs straight from the hutch. There were vats of soup and the occasional hamburger. On Friday night, when Ethan himself cooked, he roasted Italian peppers over hot coals. He tossed a salad of fresh greens, goat cheese, and pecans. Grilled tromboncino summer squash was laid over brown rice with a sweet-and-hot-pepper sauce. For dessert we had sorghum pudding and fried apples and strawberry jam. Although the PA was free of drugs, alcohol, and tobacco, we celebrated with a fermented “cup of joy,” a mix of hard cider and water kefir. The feast was delicious, the kind of farm‑to‑table spread that would cost a fortune in a city.

The Possibility Alliance used no industrial fuels. Without gas or electricity, they relied primarily on wood and the sun. Without chainsaws or trucks, they felled trees with handsaws and hauled the timber across the eighty acres with handcarts or horse-drawn wagons. Before storing the wood for winter, they cut it into lengths of three feet, a practice to discourage gorging: the stove accepted wood in one-foot pieces, so if you wanted to feed the fire, you first had to cut the wood, which not only made you think hard about how much you really wanted that extra warmth, but also warmed you in the process.

Most of the year they cooked outdoors on “rocket stoves,” highly efficient steel cylinders that burned finger-width kindling. They baked cakes and casseroles and heated pails of dishwater in solar ovens, steel boxes flanked by mirrors which, when oriented south on a sunny day, cooked food at 300 degrees.

But their focus was not limited to the ecological. When I was there, members had just taken the bus to St. Louis to join the protests in Ferguson. Ethan had been arrested twice in recent years, for blocking the entrance to a nuclear-weapons factory in Kansas City and for blocking fracking trucks in Minnesota. They got their news through newspapers and phone calls.

One afternoon Ethan taught a workshop on the history of nonviolence while his daughter Etta squirmed on his lap. A dozen of us sat in the shade of the walnut tree, partial relief from the muggy heat. It was boring stuff for a six-year-old. She wanted to go swimming. But when Ethan read a passage from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Etta climbed his shoulder and whispered a question.

“A prison is usually long-term,” he told her, “but a jail is just for a weekend.”

He gave an example of how nonviolence doesn’t always work, at least not in the short term. A group of Jews in Germany were ordered to remove their clothing before being killed. They refused. They were gunned down fully dressed, holding on to their dignity. But their refusal humanized them to the soldiers.

“Tell me that story again so I can understand it,” said Etta.

“Well, the people refused to take off their clothes when the Nazis ordered them to, hanging on to their freedom to choose,” Ethan said. “They were killed but their courage impacted the hearts of the Nazis. Their murderers later put down their guns and left the Nazi Party because they knew they had killed a human being, not an animal.”

Etta chewed this fact silently while Ethan continued the lesson. On a recent visit with family, Etta had watched a television report about three Iraqi children killed by a bomb. She wept. She could not understand how the grown-ups were able to carry on without grieving.

“We need millions of people,” Ethan told us. “Gandhi’s ashram took fifteen years to start the Salt March. We are midwives of the new world. It’s going to be a bloody mess, but you are birthing your dreams.”

Ethan and Sarah spent their very first night in Missouri in sleeping bags on the wood floor of the old cottage. They burned candles and lit a wood fire in an old coal stove. A friend had left them a box of food in the basement, so they dined on cereal and powdered milk. Sarah was far enough into her pregnancy that it was uncomfortable to sleep on a thin camping pad. Ethan knew he would have to get a mattress soon. There was not only no furniture; there was also no toilet, bathtub, sink, counters, shelves, or cookstove. In the pantry a single spigot sprouted from the floor like a weed, with no basin to catch the water.

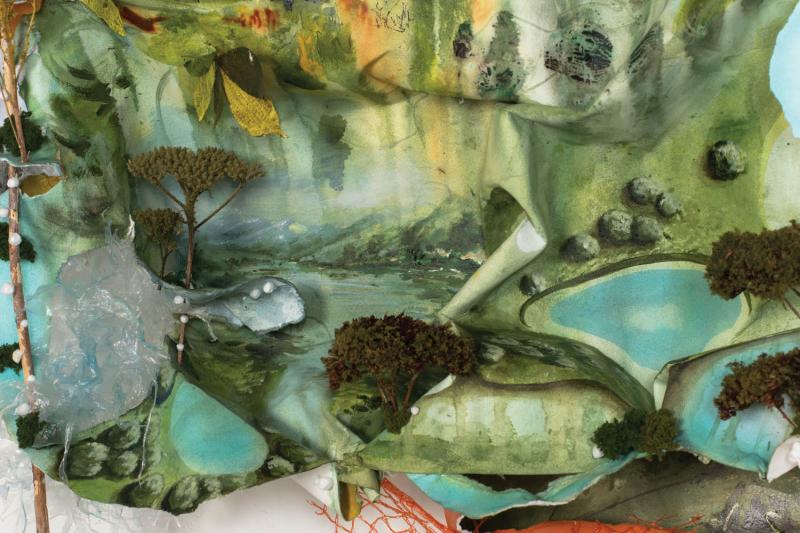

They had stepped into a previous century, one without plastic, carpet, plywood, paneling, light fixtures, outlets, or switches. The doors and window frames and molding were handcrafted wood, the grain golden beneath antique lacquer, and the place had the sweet musk of an old attic. Sarah loved it. It was a blank canvas on which to paint their new life.

But Ethan was struck by the emptiness of it. Two days later Sarah left to visit her grandparents in Iowa. After the ride from the train station, she had decided her belly was too big for bicycling, so Ethan walked her the six miles to the train station. Then he pedaled back to the desolate homestead and wrote in his journal.

Questioning our decision. Overwhelmed by all that needs to be done to create a self-sufficient homestead. Afraid of being judged by the conservative Christian community nearby. I only thought about ticks and chiggers as I walked the land. Barbwire everywhere. How the hell did I end up in Missouri. Holy shitballs!

Ethan had not aspired to be a farmer. Or for that matter a homesteader. His path to La Plata started with a greater ambition. He wanted to uplift all life, to help humanity save itself! Or in the parlance of the comic-book heroes he had always loved, Ethan wanted to save the world.

Seven years earlier, costumed in a superhero’s cape and tights, he had begun his quest to do just that. In May 2000, with Al Gore and George W. Bush having secured presidential nominations, he and a group of friends pedaled away from downtown Seattle en route to his hometown of Gloucester, Massachusetts. The journey’s purpose, as stated in a letter he distributed: “to DO GOOD!!!” In addition to raising money for Habitat for Humanity and the Center for Appropriate Transport, the bedecked riders would volunteer at schools, churches, and charities. And finally: “Along our ride where ever we see someone in need of assistance we shall stop and offer our humble and spontaneous service.”

The crew was a ragtag assortment of superheroes, such as Hug Man, Velvet Revolution, and Turquoise Seeker. Ethan wore a red satin cape, shorts over long johns, and a red shirt emblazoned with the letters BE, for his superhero name, Blazing Echidna, inspired by the endangered egg-laying, spiny anteater that dwells in New Guinea and Indonesia. Their first heroic act: They changed a flat tire for a family sedan. Then they helped a man load furniture into his daughter’s apartment.

None of Ethan’s family or friends found this behavior odd for a thirty-year-old man. Since boyhood he had loved comics and even dressed as a caped crusader when it wasn’t Halloween. He was drawn to the myth of the hero who risked his life—for free!— to save the world. As a lifeguard on Massachusetts beaches, he conscripted the younger kids to don towels as capes and compete to pick up the most trash. “He never gave a shit about what anyone thinks,” said his brother, Sean. “He would play with GI Joe dolls in the dorm—and people still liked him.” A cartoonist, Ethan later took a summer internship at Marvel Comics in New York City.

Ethan grew up lower-middle-class in the rough-edged fishing village of Gloucester. His father was a social worker, his mother a nurse. He attended the University of Vermont on a partial scholarship, worked, and took out loans, which he promptly repaid by working as an outdoor educator in the Chesapeake Bay and on California’s Catalina Island.

Ethan was exuberant and goofy and passionate. He was nearly six feet tall, barrel-chested, with close-shorn and uncombed hair. He inspired his coworkers and students to dress in elaborate costumes and perform skits and songs. He transformed into SLOP Man (Stuff Left on Plates!) to persuade kids not to waste food. He invented contests. While traveling the world with his friend Brian Thomas, Ethan decreed that when in New Zealand they would neither drive a car nor travel on buses. Hitchhiking only. Why? More fun! Brian was Huck Finn to Ethan’s Tom Sawyer. Brian began to juggle on the side of the road, and Ethan drew a cartoon sign that read, will tell jokes and stories, and before long they were picked up. In Indonesia, Ethan concocted another challenge: The friends would travel only in the cheapest seats available—third-class ferries and local microbuses. They lived like the locals, even learned the language. These constraints—no matter how artificial—brought them closer to the local people and made the adventure all the grander.

Ethan’s playfulness was tempered by a growing grief at the state of the world. In Ecuador he visited plantations and learned that the lovable, innocuous-seeming banana caused the death of hundreds of workers, who are exposed to noxious chemicals and grueling work conditions. He saw firsthand the devastation wreaked by Texaco’s oil fields in Lago Agrio, Ecuador—18 billion gallons of wastewater in open pits. The petrol was destined for the United States, and yet when Ethan recounted what he’d seen, his friends told him he was mistaken: If something that terrible had actually occurred, they would have seen it on the news.

“It was the first time I realized that the media twisted the world,” Ethan told me. “Here I was witnessing an absolute nightmare, and yet nobody was hearing about it in the States.” (After nearly two decades of lawsuits, an Ecuadorian court ordered Texaco’s parent company, Chevron, to pay more than $9 billion in damages, a judgment the company refused to pay and that a US court refused to enforce.) In Kenya he visited a dump where scavengers picked through heaps of garbage for anything edible or usable. He saw pickers at a flower plantation corralled like prisoners by armed guards. In high school he had pinned a carnation on his prom date. Was this where it had come from?

While these losses of innocence are standard fare for a certain type of left-leaning college graduate, Ethan’s response was singular. He determined that what enabled the system of pollution and exploitation, and even killing, was his own participation in it. Through the nineties, the decade of a booming stock market and gas-gulping sports trucks and behemoth mansions, Ethan began to simplify.

In February 2001, Sarah arrived in Oregon nursing a vision. She wanted to live close to nature, and she wanted life to be beautiful. She picked vegetables from the garden and flung them in the pan, never following recipes. She detested foods that suffocated in plastic wrappers. She preferred the glow of candles to the glare of lightbulbs. She hated the itch of polyester against her skin and adored smooth cotton, light linen, and soft wool. She collected secondhand fabrics and sewed her own clothes without a pattern, cutting and stitching by instinct. She loved the crackle and pine perfume of a woodstove, and she choked on the recirculated huff of gas furnaces and the metallic whiff of glowing electrical rods.

She had been this way as long as she could remember. On a family trip to Amish country she had seen a horse-drawn buggy and begged her father to buy it. Growing up in Houston, the daughter of a college professor and health educator, she pored over back issues of National Geographic and Sierra magazine, enthralled by wild nature and indigenous tribes and heartbroken by their looming extinction. She devoured stories in Greenpeace Quarterly about rebels who risked their lives to save dolphins and redwoods. In high school, while touring Europe with her father and his college history students, she swooned for French culture: the language and cheese, the poetry and art, the villages and rolling pastures of hand-piled haystacks. She sang opera. She sewed robes and costumes to don at Halloween and the Renaissance Faire. During a semester abroad in Cameroon she became fluent in French and drew an invitation to hunt forest rats with Bagyeli Pygmies. She enrolled in a permaculture course on the Navajo Nation and herded sheep for a summer, living happily without electricity or plumbing.

Sarah knew that she could never achieve her vision alone. It was too much work, too much isolation. Like so many utopians before her, she knew that only a community based on shared values could succeed. Arriving in Oregon, she began an eight-month apprenticeship at Lost Valley, a community for simple living. Their vision was less radical than hers—they used electricity—but they at least taught organic gardening. It was a start.

After college at Grinnell, in Iowa, where she majored in anthropology, she had forgone the competitive world of professional singing and instead worked as an au pair in Switzerland, then moved with a boyfriend to Japan to teach English and repay her college loans. When she revealed her desire to move to Lost Valley, her boyfriend was proud that she was following her dream, but he didn’t want to live in an intentional community. After their seven years together she went to Oregon without him. She observed, seeping up from within her, a small prayer: If there is someone out there who can help me manifest this vision, let him appear.

A few weeks later, Sarah was invited to a May Day celebration. From an old sheet she sewed herself a white cotton dress. She feasted and danced around the maypole. Despite her Methodist upbringing, she didn’t bat an eye at the pagan tropes. In high school she had become disillusioned when her minister had remained silent during the first Gulf War, as Sarah believed that the core of Christianity was peace. She’d started a recycling program at the church, only to see parishioners amble past her bins and toss their soda cans into the garbage. Around the same time, Sarah’s mother announced that she would stay home on Sunday mornings and tend her vegetable garden; she felt closer to the spirit there. Mother and daughter dabbled in Zen meditation, and Sarah’s parents eventually became Quakers. Repelled by the patriarchy of Christianity, Sarah studied Earth-based spirituality. In Japan she and her friends had invented their own rituals, including eating eggs and seeds to celebrate spring.

As night arrived, the May Day revelers gathered around a heap of kindling and logs. Something stirred overhead in the tree limbs. With a snapping of branches a creature fell to earth, a silhouette brandishing a flaming baton. On closer inspection, they saw that it was a man, naked, his head shaved bald, bedecked with moss and garlands of leaves. “I am Spring!” the satyr bellowed, and between writhing in the mud and darting past the woodpile, he delivered a soliloquy about the renewal of life, the sap coursing through his blood. He commanded the revelers to remove their shoes and feel the earth between their toes. He thrust his torch into the pyre, and a giant bonfire crackled in the night.

That night as Sarah zipped up her sleeping bag in one of the group tents, she found herself beside this odd beast. He was certainly not her type: She imagined herself with an introvert, a lover of classical music and poetry. The druid—or whatever he was—offered to tell her a bedtime story. She consented. He recounted a Maori myth of a mist maiden, the story of how rainbows were born. Sarah was charmed, and freezing. Then he suggested that they zip their sleeping bags together.

“No, thank you,” she said, but in the morning when he asked to see her again she told him to ring the house at Lost Valley. A few days later the creature called and asked her on a date. She resisted. He called again. She begged off, asked if he’d take a rain check.

“I’d take a thousand rain checks.”

Sarah agreed to meet him at a party at Lost Valley. He would ride his bike the forty miles to get there. As she waited she realized she felt giddy. She had not dated much since high school. She’d had only the one boyfriend, and they had met the first day of college. She felt somehow betrothed already to this stranger. She fixed herself a whole quart of chamomile tea.

When he arrived, the two peeled away from the party and walked along the creek to a green pool. “I’m going to jump in,” Ethan said, and asked if she wanted to join. Sarah just about choked. She’d been tempted by the creek, but the water was too cold! And besides, although she knew that skinny-dipping was normal in Oregon, she had never actually done it.

“A friend of mine just told me that anytime you want to jump in a body of water but don’t,” Ethan said, “you lose part of your life force.”

Heart pounding, Sarah dropped her clothes in a heap on the fir needles and splashed into the cold. She felt alive.

No sooner had they arrived in La Plata than Ethan was flung into doubt. “Overwhelmed,” he wrote in his journal. “Kicking through piles of plastic and rusted steel. Confusion: things break, important information ends up in the fire, books are lost in the mail and the plumbing leaks.” Like others before him who felt they had been called to create a better society, he wondered if he had gotten the wrong message. “The universe seems more interested in having me surrender than actually install[ing] any infrastructure for living simply.”

Ethan slipped into depression. His doubts about Missouri deepened his ambivalence about becoming a father. He suffered yet another relapse of the Lyme disease he had contracted a decade earlier, and some days as his pregnant wife planted trees and hoed the garden, Ethan lay miserably in bed. The community still had only one other resident, twenty-year-old Katrina Gimbel, who was dazzlingly competent at gardening, planting, and cooking, but who was nonetheless just one person. A late frost killed most of the fruit blossoms. They had committed three years to this experiment, and Ethan was already counting the days. He told Sarah they should admit defeat and start searching for something else.

It was not the first time Sarah’s fierce vision for a simple life conflicted with her love for a man. And her easy smile and lovely singing voice belied a will as steely as that of her pioneer forebears.

“If you need to go, then go,” she told her husband. “But I’m staying here.”

She told him that if he found someplace he liked more, he should spend a few months there alone to be sure it suited him. She wasn’t willing to follow him on some quest. Forced to decide, Ethan chose Sarah.

The birth of the baby, just four months after their arrival, put his commitment to an even harsher test. After three days of home labor, the midwife sent Sarah to the hospital. For the first time in years, Ethan rode in a car, racing with his wife in his mother’s sedan to Kirksville, the closest major town, fourteen miles away. A healthy girl, Etta, was delivered, but days later Ethan rushed with Sarah back to the hospital; she had a life-threatening blood clot. She was bedridden and medicated for nine months. The family had no health insurance. The hospital bill topped $17,000. Since they had no income, it was paid by Medicaid. Accepting aid violated Ethan’s goal to live independent of the government, but while they were willing to forsake lightbulbs and cars for their beliefs, and though they were willing to risk their lives for some of those beliefs, this was not one of them.

Caring for a sick wife and a newborn proved too difficult on the farm. The family spent three weeks with Sarah’s mother, who had rented a house in La Plata to be near them. With her and Ethan caring for Sarah and Etta, Katrina ran the farm the best she could. Chores went undone. Ethan had always known that he and Sarah could not go it alone, but now they urgently needed additional able bodies. Dire times required dire measures. Using his mother‑in‑law’s e-mail account, Ethan sent his first—and only—e-mail: a plea to the superheroes for help.

But nobody showed up. The revolution had stumbled at the gate. Ethan itemized his grievances in his journal:

• Poison oak everywhere, impossible to walk in woods in the summer.

• Many skilled visitors planning to come for a month or longer did not actually ever come, none of them.

• Another donor offered funds and then reconsidered.

• Someone w/ no skills, a bad back and small motion disorder is the only help so far from nearby ecovillage. Ha!

He railed against the spiritual teachings that had led him this far. “I have been following your god damn eight-fold path for years now. I am not smiling. I want to kill somebody…So kiss my ass Buddha.”

One day, he pedaled fourteen miles along the highway to Kirksville to pick up an order of bulk food with the bike trailer. On the way home a thunderstorm burst, soaking the rice and flour. Then his tire popped. He huddled on the shoulder, patching the flat, as semis blasted by. “I’ve never been suicidal,” he told me, “but at that moment I wouldn’t have minded if one of the trucks just did me in.”

The family returned to the homestead. Finally a lone superhero answered Ethan’s call. CompashMan, a.k.a. Christian Shearer, flew in from Korea, where he had been teaching a permaculture course. He stayed six weeks and alongside Katrina and Ethan whipped the place into shape. They survived through the fall and winter largely on turnips.

Ethan began to see that landing in Missouri was not bad luck but the logical destination of his life’s path. He had set out to reverse the damage done by global capitalism. But globalization’s victims were not in the places he loved: the Massachusetts beaches and California islands, the Vermont mountains and Oregon forests. Those places prospered in the consumer economy. They had that intangible thing that Americans seemed to value above all: lifestyle. They had ski hills and seashores and national parks. They had universities that attracted start- ups and wine bars and indie bookstores. It was admirable that Americans had come to appreciate natural beauty, and were willing to pass laws to preserve it and pay a premium to live near it. But these places were becoming as exclusive as New York and San Francisco: To live there you had to work in some thriving industry like finance, tech, or entertainment, which were the ones that benefited most from globalization. People who worked in “old industries” like farming and manufacturing could not afford to live in these scenic, vibrant places.

One advantage of the Midwest for Ethan was that land was cheap, which was a result of economic stagnation, which was a result of global economic forces. While coastal cities and college towns thrived, the heartland declined, both its factory hubs like Detroit, Cleveland, Gary, and St. Louis, and its thousands of farm towns like La Plata. Family farmers had been pressured during the Nixon years to compete on the international market, lured deep into debt by low interest rates to buy big machinery and more land. With fewer humans required to cultivate larger tracts and with profit margins thinning, farm towns declined. When the Fed raised interest rates to stop inflation, farmers who had relied on easy credit suffered. President Jimmy Carter’s grain embargo had the unintended result of dropping the bottom out from under wheat prices. More small farms failed and were gobbled up by big farms that required fewer farmers. The population of farm towns dwindled. The survivors, to remain competitive, bought the latest petro-fertilizers, pesticides, and GMO seeds. The romanticized American version of a farmer milking cows and picking crops beneath blue skies was increasingly being replaced by that of a farmer doing something like factory work: applying toxins with gigantic machines.

Meanwhile, in the towns, the mom-and-pop hardware stores and grocers tried to compete with Walmart and Home Depot, which set up outposts twenty miles away. These big-box stores were the true geniuses of globalization, having figured out how to bring products from China to the Midwest to sell more cheaply than the goods actually manufactured in the Midwest. Free-trade agreements allowed factories and farms in Mexico to undersell those in America. Local jobs on farms and in factories were replaced by those in sales and customer service, most of which paid minimum wage and lacked the benefits of union factory jobs or the self-determination and equity of owning a farm. As economic security dwindled, the one thing that remained relatively inexpensive was gasoline, allowing midwesterners to drive from shuttered villages like La Plata to the nearest big-box stores in Kirksville. La Plata, much more than Eugene, was the kind of place where Ethan’s vision of a neo-agrarian revolution could do the most good.

What’s more, Ethan was learning that he had more in common with his conservative Christian neighbors than he did with the radical activists back in Oregon. On the night of his and Sarah’s arrival, their neighbors Don and Dana Miller had stuffed the stove with wood to welcome them. They lent them a card table and folding chairs and invited them to dinner the first week. Ethan cringed at their framed, autographed portrait of George W. Bush, but the fried chicken was tasty.

He saw that their neighbors shared so many of his values: a commitment to physical labor, frugality, and doing things yourself rather than paying someone else to do it or make it. While buying supplies at the hardware store, he told the clerk about how his Oregon friends had been forced to demolish a cob house because it wasn’t up to code. “If the county tried to tear down a house here,” said the man, “we’d meet them at the gate, and it wouldn’t happen. And if it did happen it would be over my dead body.” Nobody in La Plata was bragging that their coffee from Guatemala was fair trade or that their coconut ice cream from Thailand was organic. Don and Dana Miller ate their own cows. Both families had moral qualms about supporting the federal government with tax dollars. And though they might use different vocabulary to describe it, both families tried to live an ethical life based largely on the teachings of Jesus.

By year’s end, Ethan’s exuberance had returned. “This is an update from the only petroleum-free, electricity-free, and car-free center of its kind in all of North America,” he gushed in a letter to donors. “We are a sanctuary and educational center committed to outward service, political and cultural change, simple and sustainable living, inner work (prayer, meditation and present moment awareness), and hospitality.”

Despite the setbacks, they had planted more than 250 native fruit and nut trees and created four vegetable gardens. “Our flock of chickens is up to 35, and two pregnant goats have joined us and will be kidding in February, which means milk, yogurt and cheese!” He noted that his family was “still living under the poverty line, which enables us to be war tax resisters and socially and economically stand by our vow to ‘love our enemies.’ ” He specifically thanked the “amazing neighbors, Don and Dana Miller, who have supported us in so many ways, from lending us their wheelbarrow for 9 months, supplying rides to the hospital and hosting our families when they visit.” Ethan and Sarah had hosted a hundred visitors, started a bike co‑op in Kirksville, and joined local farmers in blocking corporate pig farms from colonizing the county. And they had come up with a name for their experiment: the Possibility Alliance. The revolution was underway.