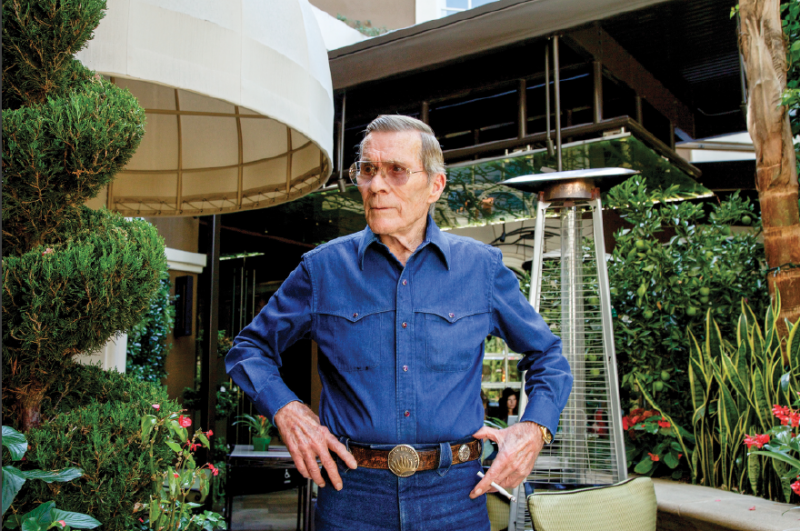

Maybe he was falling off a burning building, or taking a stiff punch to the chin. Swinging from the mast of a pirate ship, or redlining the getaway car in a bank heist gone wrong. If you’ve watched blockbuster action movies over the past few decades, odds are that J. Mark Donaldson has turned up on screen at some point. With a leading man’s build, bulletproof hair, and rough-hewn good looks, he can easily be mistaken for Harrison Ford or Michael Douglas in fast motion. His mother swears that people recognize him when they go out together. He insists they don’t, and that’s the way he likes it.

Donaldson is a professional stuntman, the guy who doubles for brand-name stars too valuable to a production to do the real stunts, despite what many of them like to claim. The car hit. The high fall. The naked burn. With the right team and preparation, he’ll do almost anything so long as he gets to return to his quiet ranch house in the canyon country north of Los Angeles, and no one is lurking in the bushes with a camera. “Let the actors take the credit, that’s what we’re there to do,” he says in his easy Louisiana drawl. “We’re there to make them look good.”

And to take the pain that’s coming. With risk there’s always the chance of pain; if there wasn’t, he would not have a job. Practice helps, but “more often than not, you just close your eyes and go for it,” he concedes.

Once Donaldson had to double for a thirteen-year-old paperboy who rides a bike across a wooden bridge that collapses. The bridge was already built when he arrived on set, forcing him to fall seventeen feet into eighteen inches of water with his arms out. Had the bridge been moved a short distance, he would have fallen into four feet of water, no problem. But there was no time (read: no money). It took three days of walking the bridge and sizing it up before he knew he could do the stunt. “My thinking was if I walk away with a broken arm, chipped tooth and broken nose, I’ll be lucky,” he recalls. He had to do the stunt twice. The first fall nearly knocked him out. Dazed, he got up right away to do it again before he lost his nerve.

Big risks have brought a few stuntmen fame and fortune. Hal Needham, the stepson of an Arkansas sharecropper, went from jumping horses at a gallop to soaring over canals in rocket-powered pickup trucks to directing films. In Hooper (1978), his close friend and one-time roommate Burt Reynolds played a stuntman modeled after him. He also directed Reynolds in Smokey and the Bandit and the Cannonball Run movies. Needham and William L. Fredrick were honored with a Scientific and Engineering Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the design and development of the Shotmaker Elite camera car and crane, which markedly improved the filming of action sequences. As the highest paid stuntman in the world, he later bought a NASCAR team and owned the first land vehicle to break the speed of sound. He published a breezy autobiography, Stuntman!: My Car-Crashing, Plane-Jumping, Bone-Breaking, Death-Defying Hollywood Life (2011). This past December, he was awarded an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement. He earned it the hard way, breaking fifty-six bones—including his back, twice.

Over the years, a higher profile and the formation of stunt groups helped secure greater benefits for card-carrying stuntmen and stuntwomen. Those who work enough and qualify for membership in the Screen Actors Guild enjoy some of the best healthcare coverage around, with the guarantee of a reduced pension beyond the age of fifty-five, and a full pension at sixty-five, should they live to see the day. Although there are no statistics on life expectancy, it was once typical for one or two stunt people to die each year on the job, most commonly in high falls. Any stunt person of a certain age has grim stories of friends lost.

These days, no one will do a ninety-foot fall without being connected to Kevlar cable that can be digitally erased in postproduction. Advances in computer-generated imagery (CGI) have made catastrophic accidents less likely, but there are downsides. Fewer jobs are available. High-speed winches mean greater wear and tear on the body over time. Veteran stunt people also lament how artificial the action can feel to an audience, that viewers subconsciously disengage. It’s often assumed an action shot is fake even when it’s not. “I prefer the old way of doing things, where it’s: Did I really just see what I think I saw? You let your mind create the story,” says Donaldson.

Growing up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Donaldson knew he’d never be a 9-to-5 man. Steve McQueen and his motorcycle loomed large, and as a teenager he started racing competitively. He saw stunts in movies and knew that he wanted to do them. The film industry was closemouthed back then, leaving no choice but to show up. At twenty-two, he drove out to Hollywood and started “hustling,” industry slang for networking—sneaking on sets to talk to the stunt coordinator, hanging around the right gyms—until a breakthrough.

Now fifty-six, Donaldson admits that his chosen career has taken a toll. His knees ache, and his shoulders have lost their strength. His memory lets him down, and he notices similar lapses among stuntmen friends, though the stories get better with age. He still likes to race motorcycles at the track on the weekends, where he lets other competitors surge ahead so he can catch up to them for fun. But at a recent event he blacked out and crashed—a by-product, he reckons, of having had too many concussions to count.

Donaldson expresses no regrets. He has worked with the top actors and directors and taken his family to exotic locations around the world. He currently serves as president of the Stuntmen’s Association of Motion Pictures, the oldest group of its kind. Though he’s at home more than usual, Donaldson still gets the call. “This is a very unforgiving business, and there’s always someone right behind you waiting to take your job,” he says, pausing to smile. “I always like to say that I don’t mind being number 357 on the list of guys to hire, as long as 356 said ‘No’.”

For seasoned professionals and newcomers alike, hustling remains a constant. As does the intense physical training in disciplines ranging from stunt driving to martial arts. But a changing industry demands a new archetype, at once more flexible and specialized. A rising stunt person might take acting classes, audition for small speaking parts, and operate a business on the side. All-rounder Jayson Dumenigo runs a stunt-rigging company that specializes in fire setups and recently set a Guinness World Record for the longest full-body burn without oxygen. Brady Romberg, a dead ringer and regular double for Justin Timberlake, is trying to produce a live show that celebrates stunt legends. He is also a free-runner, a sport that emphasizes athleticism and momentum over gravity. His sister, Luci, enters Red Bull Art of Motion competitions—combining free-running, parkour, martial arts, and gymnastics—when she’s not back-flipping through films and commercials. They may perform old-school swordfights, but they do them in motion-capture suits for 3D movies.

They are the new breed.