The two-dozen men and women had been at it for the better part of the afternoon. They sat around a long folding table littered with schedules, notebooks, and Styrofoam cups filled with dregs of cold coffee and floating cigarette butts. The man at the head of the table—stocky, confident, with thick Brylcreemed hair—lobbed a final question down the table.

“How long does he have?”

“Sixty seconds from the time we seal him up.”

“Good. He shouldn’t hurry. Smooth and slow. I want to see his robes catch fire and burn off. Then he just keeps walking until he’s swallowed up by the flames. This is Satan, for God’s sake. It should look like he’s just going to grab a beer or something.”

“It’s also a one-shot,” a round-faced man said through the Marlboro between his lips. “No money for take two. Okay … final budgets on my desk by six. Crew call’s 2 p.m. Oh, and our mail boy, Chip, is going to be hanging out with us for most of the shoot. Try not to let him annoy you with too many questions.” The production manager winked at me as he said this. Every crew member at the table turned and either smiled or nodded a welcome to the saucer-eyed sixteen-year-old sitting in the corner.

It was June 1973, and this was to be my first experience on a picture from start to finish; a golden ticket to observe a film crew at work and soak up as much of it as I could.

The film was an ABC Movie of the Week called Satan’s School for Girls, a title that still elicits chuckles after almost forty years, yet that is brilliant in its pithy self-description. It was a sensationalistic horror picture, loaded with special effects, a couple of nifty stunts, atmospheric production design, and most important, a cast of beautiful young actresses.

I was in heaven.

And while I didn’t realize it at the time, many of those faces that turned to greet me were about to become some of my most memorable teachers.

Every time an awards show goes overschedule because of an avalanche of “thank-yous” in a mind-numbing amount of categories, we’re reminded that films are a highly collaborative art form; with the holy trinity of writer, director, and actor the most recognizable of the creative forces. On most feature films, there’s usually a degree of jockeying to stake artistic claim on the project. Directors with enough clout get “A Film by” credit. Actors whose popularity may draw box-office get their name above the title. And writers … ah, well, writers. They’ve always felt like the red-headed stepchildren of the film business. Jack Warner called them nothing but “schmucks with Underwoods” (once upon a time, a popular brand of typewriter). After years of dismissive abuse at the hands of studio chiefs, writers were finally able to gain the respect they sought with the advent of television, where they still reign supreme.

Television is about volume and consistency, and the powers-that-be recognized that any writers who could reliably crank out twenty-plus episodes of quality drama or comedy every season were worth their weight in back-end profit. In the feature business, however, writers still have to be content with nice paychecks, an occasional nod from their peers, and the satisfaction in the knowledge that the entire filmmaking process begins with an empty page and a writer’s imagination.

In truth, all three need each other equally. Without the script, there’s no story to tell and no characters for the actors to bring to life. And since a film is moving pictures, not moving words, it requires the imagination and talent of a director to translate a script into the visuals of the medium, working with the actors and a myriad of creative departments to properly convey the writer’s work as the director interprets it. Even as it starts, the scenario is complex.

There’s an additional figure atop the filmmaking food chain, hiding behind the curtain, usually on the phone or in a meeting: the producer. The producer’s artistic contributions may not be as tangible on screen, but he or she is the connective tissue of a picture. The producer shepherds the script, assembles the talent, procures the financing, deals with the inevitable egos, and attempts to keep all the creative machinery well-oiled and moving forward. That’s an art form in itself, and once a film is in production, it can be like trying to hold the reins of a team of galloping horses in your teeth to keep your arms free to herd cats.

But filmmaking isn’t just a producer assembling a creative three-legged stool. It’s more akin to a large Jenga tower. If there are too many weak links, it can all come crashing down, regardless of how talented the key players may be. Every department brings necessary spice to the stew, and while cinematographers, art directors, costumers, editors, makeup artists, hair stylists, sound mixers, and other members of the team might be given their recognition on awards-show night, the winners are inevitably hustled offstage in a race to get to the more popular categories. Some are even relegated to a separate, unaired ceremony described as “technical” awards. While their work may indeed be highly technical, they are artists all the same, just as much as any of the names above the title.

During the production process, the collective known as “the crew” is the heart and soul of a film, whether it’s a $300 million blockbuster, a low-budget tv movie, or just another episode of a tv series. Working on set with a talented crew is like being inside a magic act. Literally and figuratively: walls suddenly disappear then reappear elsewhere, giant cranes and scaffolding are erected and disassembled in minutes, night turns to day and then back again, rain and wind appear on cue, and weary thespians who might have been a tad over-served the night before are transformed into unblemished, idealized versions of themselves.

As Irving Berlin has famously pointed out, there really is no business like show business. And after sitting intently through the three-hour production meeting in a smoke-filled rehearsal hall on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, where the script for Satan’s School for Girls was dissected scene by scene, line by line, each department confirming what was expected of it, I couldn’t wait for the start of production the following day.

But first I had a mail run to make.

In an example of unabashed Hollywood nepotism, I’d been given a summer job in the mailroom of Spelling-Goldberg Productions (Aaron Spelling was a longtime family friend). The work consisted of copying mountains of scripts, call sheets, budgets, and reports, then delivering them to the far-flung offices and departments scattered about the Twentieth Century Fox lot.

Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg had teamed up in 1972, and the pair quickly had a hit series on the air, a police drama called The Rookies. It would be the first in a long string of successes for the two men. In the years to come, they’d produce such iconic shows as Starsky and Hutch, Charlie’s Angels, S.W.A.T., Fantasy Island, Hart to Hart, and T.J. Hooker. They were also contracted to make a number of ABC Movies of the Week every season. This anthology series of made-for-tv films was a revolutionary idea at the time, and helped ABC flex its muscles as a legitimate competitor with old stalwarts CBS and NBC.

The ninety-minute format was ideal for fast-paced, tightly woven storylines. Without the commercials, it ended up running about seventy-eight minutes: a length that would have been too short for theatrical release, but just enough for a writer to develop characters and drive them through a storyline. The six acts dictated the need for five cliffhanger points in the script—plot-twists, moments of jeopardy, or major revelations required to keep the audience tuned in through the commercial breaks. It was fertile ground for writers: film as novella. Budgets between $300,000 and $400,000 made them attractive to the network, and the early 1970s witnessed dozens of these little films on the air each year. While most of the 200 or so movies ABC commissioned were quickly forgotten thrillers and melodramas, an occasional diamond in the rough emerged.

A young Steven Spielberg garnered attention directing Duel. It was a Richard Matheson script starring Dennis Weaver as an everyman being chased across a deserted highway by a malevolent tanker truck in a kill-or-be-killed scenario that showcased Spielberg’s impressive ability to keep an audience on the edge of its seat—even with the multiple commercial breaks interrupting the action.

Brian’s Song, the real-life story of NFL player Brian Piccolo’s battle with cancer and his friendship with fellow player Gale Sayers, was a groundbreaking moment in television. Starring James Caan and Billy Dee Williams, deftly written by William Blinn and directed by Buzz Kulik, the interracial bromance was seen by half the country’s television sets in use—leaving both men and women to replenish their Kleenex the following day. It was a huge success with both audiences and critics, and is still considered by some to be the finest tv movie ever made.

For ABC, an added benefit of the format was its use as a development tool. Networks spend millions of dollars every year developing and producing pilot episodes for ideas that never go to series. Most of the time, those pilots don’t even get out, becoming expensive write-offs. In the early 1970s, ABC commissioned a number of pilots as Movies of the Week, allowing them to not only gauge the audience’s reaction to the idea, but to also recoup the development and production costs through the advertising revenues. Popular series such as The Rookies, Wonder Woman, The Six Million Dollar Man, and Starsky and Hutch all began as ABC Movies of the Week.

Satan’s School for Girls was never destined for greatness (though it did develop enough of a cult following to be remade in 2000). But I was no less excited for the opportunity to be a part of it, even as the mailroom delivery boy who was allowed to spend time on the set.

For a learning experience, Aaron Spelling had told me I could choose one of that summer’s Movie of the Week productions to follow from start to finish. A lifelong fan of the horror genre, I had already devoured each new draft of Satan’s School for Girls as it came through the mail room. It told the story of a young woman who goes undercover in a New England boarding school to find out what drove her sister to commit suicide, discovering along the way a satanic cult led by one of the teachers. It was a deliciously cheesy mix of suspense, campy clichés, and over-the-top set pieces. And the promise of a bevy of young actresses appealed to my baser instincts. I was sixteen years old, after all.

It was the first of many opportunities Spelling would offer me. A few years later, I would become a production assistant on Fantasy Island, where he gave me my first shot at writing teleplays. Years later, he brought me back into the fold to produce over two-hundred hours of a Fox Network series that came to represent the zeitgeist of the nineties—Melrose Place. Aaron was an amazingly talented and prolific writer/producer, and in 1973, Spelling-Goldberg Productions dominated the Twentieth Century Fox lot.

Back in 1973, the Fox lot was a shadow of its former self. Twelve years earlier, following a financial crisis brought about by unprecedented losses from its disastrous flop Cleopatra, the company sold all 263 acres of its back lot to Alcoa, who then built what is now Century City on property that once held a large medieval village, a turn-of-the-century small town, and, where the Century Plaza Hotel stands today, a massive lake used for pirate movies, World War II Navy films, and all sorts of water-based miniature shots. Legend has it the Century Plaza spent years dealing with water-seepage problems in its subterranean parking lot: appropriate penance for constructing a hotel on sacred Hollywood ground.

Still, enough of the magic remained. The multimillion-dollar New York outdoor sets constructed four years earlier for Hello, Dolly, replete with overhead train tracks, a section of turn-of-the-century Fifth Avenue, side streets of tenement buildings, and a lushly landscaped section of Central Park, were mostly still intact. So was a small western street nestled behind a Swiss chalet known as the old “Writers Building,” where F. Scott Fitzgerald reportedly worked during his short stint in Hollywood. The commissary was located just off Peyton Place Square, where the white gazebo and park from that 1960s primetime soap still stood. The exterior of the main screening theatre was still recognizable as Commissioner Gordon’s office building from the Batman tv show. Driving my mail-boy golf cart through those streets every day was a constant reminder of just how unique this strange, intoxicating business can be; the quickly decaying facades a caution that Hollywood is all just illusion and always in flux.

One of the highlights of my mail rounds was heading up the long hill to stages 17, 18 and 19; stage 17 being home for the permanent sets of The Rookies. Outside these stages was an outdoor area where the studio stashed set pieces they weren’t sure what to do with, but didn’t want to destroy just yet. The two-story, beautifully crafted interior set of the Great Pink Sea Snail from Doctor Doolittle (another bomb that almost broke Fox) sat there for years, its pearlescent paint slowly flaking away, revealing the plaster and rusting chicken-wire frame beneath. All kinds of giant props, including full-sized spaceships from the various Irwin Allen shows—Lost in Space, The Time Tunnel, and Land of the Giants—found their final resting place here before being lost to history. It always felt like a trip through Wonderland to explore these relics.

Another bonus of making the stop at The Rookies stage was the chance of an encounter with one of its cast members, Kate Jackson, who was also going to be costarring in Satan’s School for Girls. I’d been madly in love with Kate since she first appeared on Dark Shadows, Dan Curtis’s vampire soap opera that I used to race home from grade school to watch. In person, Kate was just as pretty, sweet, and funny as I’d imagined her to be. No starlet ego on display, always a smile and warm hello.

About a week before production started on Satan’s School, I was climbing back into my mail-boy golf cart outside the stage when Kate approached me. She said she was craving a salad and asked if I would mind giving her a ride up to the commissary. Before I could stammer out a “Yes,” she flashed a mischievous smile.

“Mind if I drive?”

The next few minutes became one of those adolescent experiences seared into my brain. It turned out Kate liked driving that golf cart. And liked driving it fast. I recall going up on two wheels at one point while rounding a turn. While I must have been white as a sheet, I blithely laughed along with her—figuring if I was going to die, it would be a memorable death. She was, after all, Kate Jackson.

As we pulled to a screeching halt in front of the commissary, I told her I was going to be shadowing production on Satan’s School for Girls.

“Cool,” she smiled. “I guess that means I’ve already got a friend on set.”

She was eight years older than I, but I wanted to ask her to marry me right there. I stifled the urge, and drove off with a stupid grin.

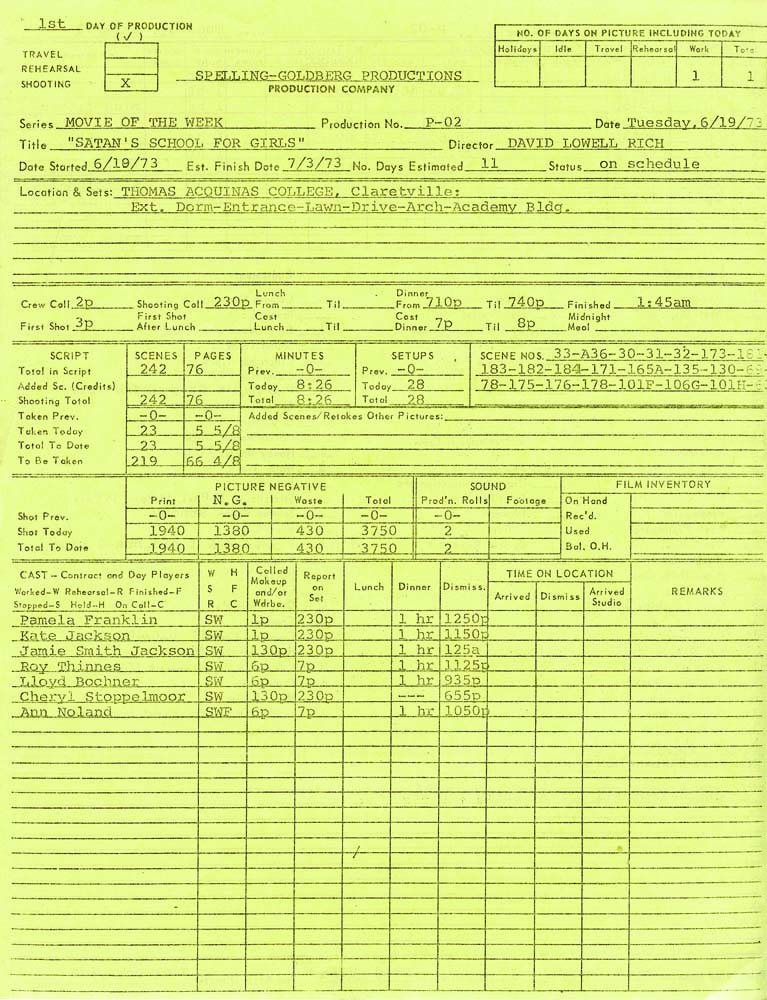

The first day of production was Tuesday, June 19, 1973.

The shooting schedule called for three days of location shooting, then eight days on various stages back at Fox Studios. The location work consisted of a few day sequences, but the bulk of the work was predominantly at night, so the first shot wasn’t scheduled until 2:30 p.m.

The exterior of the Salem Academy for Women and its surrounding grounds was shot at a mansion originally built by King Gillette, the man who popularized the safety razor. It’s a spectacular looking estate set on 588 acres in the Santa Monica Mountains (and most recently used as “the ranch” on The Biggest Loser). The fact that the script called for a 300-year-old building set in Salem, Massachusetts, and the Gillette mansion’s architecture is Spanish Colonial Revival, was one of those details overlooked. The place was affordable, it had a lake which was needed for one important sequence, and the other exterior locations required were found within a short drive.

One the first lessons I learned in making film: budget trumps logic.

I arrived at location an hour before shooting call, pulling up to the driver captain, who was holding a walkie-talkie and directing a caravan of production trucks over to a spot hidden behind a grove of trees. He recognized me from the production meeting, and when I asked where to park, he told me to just follow the trucks. But first he asked me a question.

“Know why we’re parking everything way over there?”

I told him I assumed it was to make sure the trucks wouldn’t be seen by the camera.

“Correct. But why not over there? Or over there?” He pointed out two parking lots much closer to the mansion yet still out of view. I shrugged, thinking about the day’s work as it was laid out on the call sheet. Then I remembered a discussion from the production meeting. The director wanted to see the long tree-lined driveway and bridge that passed over the large lake before reaching the mansion. He intended to film the lead character’s POV (point of view) as her car made its way up the road. Unless the trucks were hidden where they were, the POV shot would certainly find them.

“The drive-up sequence?” I asked.

“Bingo,” he said. “When we come back tomorrow, we’ll park everything over here so it’s less of a schlep to get the equipment unloaded. But today we need to hide it all.”

I didn’t think about it until later, but he didn’t have to do that. He had an army of vehicles to wrangle into place and didn’t really know me from anyone.

Yet he took the time to teach me a little something.

It was to become a familiar motif as the days progressed. I was supposed to be there to learn something, not just hang out. Many of the crew understood this, and once they sensed I was willing and sincere, they welcomed me into the fold. It was like being allowed a glimpse into some special club, with everyone eager to teach me the secret handshakes.

Even a low-budget production requires a lot of equipment. The electrical and grip department usually pulls up in a forty-foot behemoth, with lamps, stands, flags, gels, and miles of cable packed inside. Twin generators that supply the needed power are usually nestled just behind the crew cab of this monster truck. The camera department has its own van full of equipment, as does wardrobe, props, greenery, and special effects. Hair and makeup will usually have its own special trailer in which to work its magic. What’s affectionately known as the “honey wagon,” a long trailer with up to seven individual dressing rooms/bathrooms for the actors, along with additional bathrooms for the crew, is an obvious necessity. Then there are all the vehicles used in the film itself, called “picture cars.” Add in the caterer with all their equipment, and it can become quite a vehicular ballet.

While the crew got busy unloading and setting up for the first shot, I went off to find where Satan’s Girls were hanging out.

Two makeup artists were already busy with Kate Jackson and the other star of the picture, Pamela Franklin. I was a longtime fan of Pamela’s work, ever since seeing her in The Innocents, one of cinema’s finest ghost stories, in which eleven-year-old Pamela costarred with Deborah Kerr. Pamela had grown up to be a superb actress, winning plaudits as the rebellious Sandy in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, for which Maggie Smith won the Best Actress Oscar. Pamela had the unique talent to make even the most cringe-worthy dialogue (of which this script had its share) sound sincere.

Waiting their turn in the other chairs were the other two actresses who had speaking roles as students: Jamie Smith Jackson, who had just starred in a Movie of the Week about teen drug use called Go Ask Alice, and a stunning young woman named Cheryl Stoppelmoor. Later that year, Cheryl would marry Alan Ladd’s son, David, and take his last name professionally.

Aaron Spelling had an uncanny knack for finding talent, and here, three years before it was even dreamed up, he’d already paired together two of the future stars of Charlie’s Angels.

Kate waved, and introduced me to everyone. The makeup artist at work on her was a dapper man with a pencil moustache named Howard Smit. He looked up with a surprised smile.

“You’re Nancy Gates’s son, aren’t you?”

It turned out that Howard Smit was an old friend of my mother’s from their days at RKO, where my mother had been a young “contract player,” and he was fresh from MGM where he’d worked on The Wizard of Oz, among other productions. Howard would end up being an invaluable teacher over the next eleven days, imparting a font of advice about working with actors. Makeup and hair is an island unto itself, and actors can become very attached to their favorite artists and hair stylists. If an actor isn’t happy about something, odds are they will be the first to know. The makeup and hair department can be invaluable for a producer who wants to keep little problems from becoming big ones.

The director called for rehearsal of the first scene, where Pamela Franklin would drive up to be greeted by Kate, Cheryl, and Jamie and then escorted into the school. David Lowell Rich (the man at the production meeting describing how he wanted Satan to burn up) was a veteran tv director who already had twenty years of television credits under his belt. In 1973 alone he would direct four of these ABC movies. David Rich was capable, energetic, and most important, knew how to get the work done on time. He shot only what was needed, using the minimum time he could to get it, then he moved on to the next setup. There wasn’t a single day where he went into overtime. On budgets as thin as these, that made him invaluable.

After a quick rehearsal, the assistant director turned the set over to the director of photography and his crew of electricians and grips to light the first setup.

The film and television business was going through a technical revolution in the early seventies. Panavision had just developed a very quiet, modular, lightweight 35mm camera—the Panaflex. A new kind of light, called the HMI, had just been invented in Germany, and promised a more efficient and compact way to light a film set. But the transition was gradual. The new technology would eventually become standard for the next few decades, but in 1973 it was expensive and not yet perfected. Most television productions still used the old workhorse cameras—heavy, noisy Mitchell BNCs. Lighting was still accomplished with various sizes of tried and true tungsten lamps run on AC power from the generator.

Then there were the mysterious creatures called the Maxi Brutes.

The Brutes fascinated me. True to their names, they were massive, heavy, and retina-searing in their output of light. They had little chimneys on top through which waves of heat and gasses were vented. Each of these giants had its own large stand, usually with motorized lifts to raise it up high, and each requiring a dedicated electrician to monitor and service it. I wanted to know more about the Brutes. The head electrician, known as the gaffer, was busy with the director of photography lighting the scene, and I didn’t dare bother them at the moment. So I asked Tiny to fill me in on them.

I don’t recall Tiny’s real name, but his nickname belied his girth. Well over 300 pounds and always dressed in a T-shirt that looked as if it had been bought twenty years ago, Tiny was one of the electricians whose primary job was to stand on a ladder next to a Brute, aiming it where he was told, dropping huge discs of diffusion screens or colored gels in front of it, and performing the strange tasks of “striking” it and “trimming” it.

All it took was a simple “how does that thing work?” from me to launch Tiny into Carbon Arc Technology 101. He explained how the Brutes didn’t use any bulbs. Instead, they had two electrodes inside their housing, each holding two finger-thick sticks of carbon, one for the positive terminal, one for the negative, and they ran off a separate DC supply from the generator. When current was applied, the electrician would turn a dial to move the tips of the carbon together, which created an arc of electricity and an amazingly bright, steady flame. It was a pure white light, and many cameramen still claim there isn’t anything prettier than lighting with a carbon-arc Brute. But they were time consuming, and required additional electricians to man them. As the carbon stick burned, it required proper trimming every thirty minutes or so or else the lamp would start flickering, potentially ruining a take. It was the electrician’s responsibility to monitor the flame through a darkened window and alert the gaffer before a take if the lamp needed trimming.

Tiny was proud of his years in the business, rattling off the many pictures he’d worked on and the many stars he’d helped light. This was something that struck me about most everyone I talked to on the crew: the pride they took in the work they did. They certainly weren’t out there for fame or fortune. Filmmaking is tough work, with long hours in sometimes unpleasant conditions. And most everyone works for scale. But every time a crew member said they worked on this picture or on that show, the subtext was that they were a part of that production. A piece of the puzzle that made up the whole.

It was an inspiring attitude, and one that was infectious.

The director clipped through the first sequence in a couple of hours. While they were finishing the close-ups, I wandered over to see what kind of contraption two men were fastening to one of the picture cars.

Grips are responsible for all the non-electrical rigging done on a set. That includes all the various camera mounts, rolling dollies, dolly track, and the forest of stands and various flags, nets, and filters placed in front of lights to properly balance and diffuse the light to the director of photography’s satisfaction. These are the guys who, when suddenly presented with an unexpected conundrum on how to get a certain shot, eagerly rummage around in their truck, emerge with a few odd pieces of mounting hardware, and come up with the solution for the most vexing of problems. There is no “impossible” for them. Just that boogeyman on every film shoot—the clock.

The two grips explained to me the workings of the mounts they were installing on the car. A large metal bar lay across the front hood, anchored by tightened straps under the front fenders. Posts on the bar would hold two separate cameras, one pointed at the driver, another pointed straight ahead for the POV shot. Other posts would hold lamps to light the actress who would be driving, with cables tucked away and leading to the trunk, where batteries supplied the power. It was a clever contraption, able to get two separate shots in a single run up the long driveway to the school. That meant saving the twenty minutes it would take to rotate a single camera around, move the car back to the front gates, and reset all the extras wandering the grounds—more clever tricks of the trade, developed through years of experience and apprenticeship; things you just can’t learn from a book or in a classroom.

Once the daytime work was finished, and almost a hundred hot meals were served up by the caterer, the real fun began. The script had all sorts of comings and goings to be filmed at night, many taking place during a furious lightning storm. Rain was called for, but vetoed in these exteriors due to the costs. The man in charge of special effects, Logan Frazee, explained how rain could add hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to the budget. Towers would have to be built to spray the rain, requiring extra personnel. All of the equipment would need to be covered up and protected, an extra water truck brought in to pump the rain, and extra time taken for make-up, hair, and wardrobe after getting all the actors wet.

So rain was out, but wind and lightning were still in.

A movie wind machine is basically a large airplane propeller with six-foot-long blades turned by a gas engine. At full speed, it’s capable of cranking out a 100-mph wind. One of the sequences required Pamela Franklin to exit the main building, carrying a painting in one hand and a glass oil lamp in the other. Pamela is all of five feet tall and probably weighed ninety pounds soaking wet. When she first emerged from that doorway holding a large canvas, she almost took flight. Needless to say, the wind machine had to be dialed back a bit.

There was no dialing back the lightning machine, though. For many years the best lightning effect was produced using a frightening-looking device called a scissor arc. It consisted of two bundles of the same type of carbon sticks used in the Brute. The bundles were connected to a large amount of DC amperage and mounted on a metal contraption that looked like a giant pair of scissors. When the carbon bundles were brought together and touched, they set off a short circuit that sputtered and flashed with enough light to illuminate a city block. Safety warnings would be announced before each take, and once you saw the effect in action, you didn’t need to be warned more than once. Chunks of white-hot carbon would sometimes fly out, and a fireman had to be on set just in case something caught ablaze. It was incredibly dangerous and would never be allowed on a set today. When computer-controlled lightning effects were developed a few years later, the scissor arc was retired for good.

But, man, it was cool to see in action.

The first day of shooting ended around 2 a.m. I don’t think I’d learned as much in a single twelve-hour period in my life.

And there were still ten days left.

The next two days on location were filled with more fascinating revelations. The company spent an afternoon shooting at a house on nearby Malibou Lake, a development from the 1920s that has hosted hundreds of film shoots over the years, including classics such as Frankenstein and Gone With the Wind. For Satan’s School for Girls, this particular house was owned by Pamela Franklin’s character. In the opening sequence of the picture, her sister tries to find refuge there as something sinister pursues her. Whatever it is catches up to her inside. Pamela arrives home to find her sister hanging from a rafter.

I was curious why the grip department had an hour earlier call time than the rest of the crew. The location had been partly chosen because the house’s large picture windows overlooking the lake made for a sumptuous production look. The key grip explained to me that shooting in front of windows during the day requires more light on the inside than is coming in from the outside. But to get that kind of balance for film, you’d have to pump so much light in the house you’d melt your actors. The secret is to cut back on the amount of sunlight coming in. The grips accomplished this by covering the windows in a plastic that comes in large rolls. It’s called neutral density gel because it doesn’t change the color of the light, it just reduces the intensity. There were a lot of windows there, and it was a big job, taking two grips most of an hour. When the afternoon’s work was done, they had to take it all down and roll it up again.

I was beginning to understand why movies cost so much to make.

That night, back at the school, Professor Delacroix met his untimely end. Delacroix was the red herring of the script, played by an actor named Lloyd Bochner. You’re meant to think he’s the bad guy all along, but then the two leads find him half-crazed in his classroom, and he escapes by crashing through the second-story window and running off into the woods, where he falls into a pond. Out of nowhere appear a bunch of the students, with evil, vacant looks in their eyes and holding bamboo poles, which they use to push him underwater.

This took a good eight hours of work, during which my respect and empathy for Lloyd Bochner grew exponentially. Although the stunt coordinator, Charlie Picerni, made the actual leap out of the window (into a pile of cardboard boxes), it was Bochner who spent the night running through the woods, tumbling and falling, getting back up again, then finally tripping into the pond where he spent the last two hours of filming in and under the water.

It can get pretty cold at night in the mountains of L.A., even in June. Although Bochner had a wet suit on under his suit and tie, that water was freezing and particularly nasty. The call sheet reminded special effects to bring a pool skimmer to clean the algae off the top of the water prior to filming. Between takes, Bochner bobbed about in the murky water, jokingly bemoaning the actor’s lot in life.

Or maybe he wasn’t joking after all. I decided that night that being an actor might not be all it’s cut out to be.

Once filming moved back to the studio, I got the chance to learn more about the postproduction process as well. “Dailies,” the takes from the day’s work that the director wants printed-up to use while editing the film, were projected in a screening room every day after lunch for Spelling, Goldberg, and the various postproduction staff. While it was always educational listening to the executive producers’ comments on these, I was more interested in the editing process itself.

Entering the small trailers where the film editors worked, your senses were assaulted with the smell of freshly printed film and the clackity-clack sound of the Moviola machines, mixed with the soundtrack of whatever scene was running through them at the time. The Moviola was a marvelous apparatus, standard in the industry for decades as the tool used to edit film. Until it became the final product, picture and sound were on separate pieces of film. The Moviola kept them in sync, projecting the film on a small viewer and playing the soundtrack alongside it. With the touch of a lever the editor could freeze the film at the exact frame where he or she wanted to make a cut to another angle or sequence.

Once again I found someone who was eager to teach, and the editor was happy to let me watch over his shoulder, explaining the basics of the creative and mechanical aspects of film editing as he worked. Watching him piece the picture together, cut by cut, was fascinating, and I found myself bouncing between production and postproduction, soaking up as much of both worlds as I could.

As the days went on, the company would move from stage to stage, the set construction and dressing crews keeping one step ahead, finishing up building and dressing a new set just in time, then packing up and tearing down the ones that had already completed filming, like a train laying its own tracks then pulling them up again.

The electricians were kept on their toes for a number of days when the scenes called for Pamela Franklin’s character to wander through the school’s corridors, classrooms, and cellars holding an oil lamp for light (due to a conveniently scripted power outage.) They would have to pre-light the areas where the actors moved, then use a board full of dimmers to dim down one area of light while bringing up another area, in order to simulate the look of a moving light source. One lamp operator would also focus a small light on the flame itself, and if the actor and operator got out of sync it made for some amusing but unusable lighting effects.

The last couple of days involved a lot of fire work. Roy Thinnes, playing the handsome professor who turns out to be Satan, attempts to convince Pamela’s character to join his collection of acolytes. She defies him, tossing the oil lamp at him and starting the conflagration that ends the picture. The special effects team was diligent in its safety procedures, but it was still unsettling to be inside a stage while half the set is going up in flames. The final big fire stunt, where Thinnes’s character—dressed in a monk-like robe—turns and walks back into the flames, required such a large fire that it was shot outside the stage on the last night of filming.

The eleventh day went by all too quickly. I’d eventually follow the post-production process through final cut, sound-effects editing, music scoring, and sound mixing. But I missed the camaraderie of the production crew, and found myself sneaking away from the mailroom to visit them on the sets of the next movie that started the following week—a weepy melodrama called Letters From Three Lovers.

This was certain: I made a point of thanking all those who had taken the time to teach me a little about what they do. I hadn’t expected to find so many generous and talented people who would open up like that, and I felt extremely fortunate to have had the opportunity.

After viewing a final cut of the movie with the producers, I emerged from the screening room and found Kate Jackson coming out of the back entrance. She had sweet-talked the projectionist into letting her watch it from his booth. She asked my opinion of the picture. I told her I thought it came out great.

“I hated it,” she said, crinkling up her nose. “It was awful.”

She was right, of course. It was pretty bad. The actors and production team had made the best of a weak, clichéd script, but it was still pretty cringe-worthy in parts. I shrugged, tacitly agreeing with her. I wasn’t sure what else to say.

“You looked beautiful, though.”

It just popped out of my mouth. She smiled, then gave me a kiss on the cheek and thanked me. As she walked away, I knew I’d just capped off a summer I wouldn’t forget.

Oh, and that fire walk that was the big ending to the film? The one the director wanted all smooth and graceful? The stuntman tripped over a timber that was being used to hide some gas jets. Satan looked positively goofy.

But it was a one-shot. And it went into the picture.

Hey, that’s showbiz.