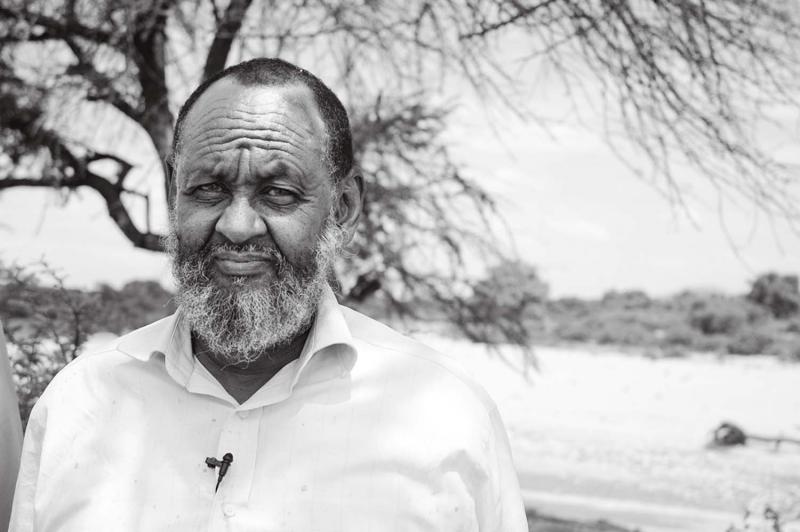

Dr. Aden Ismail, a tall, heavy-set man whose size and expensive watch marked him out as a qurbajoog, or returnee, took a few steps into his clinic, ducked a slab of broken concrete, and disappeared. “Careful,” he called back. “There could be unexploded mines here.”

I followed him over the chewed-up lip of a wall into what was let of the waiting room. The roof and two walls had collapsed. A tree grew in a roughly sketched plot of sun. Its shoaling leaves caught the light, a brief green glitter. A squatter had cleared a path through the mess, superimposing his own floor plan on the doctor’s older, remembered one. The path twisted through the rubble, terminating in little cul-desacs filled with plastic bags, laid with cardboard, scattered with shit. “Here is where I delivered the babies,” he said. “I had a team of nurses and there were ten patients staying at one time.” He smiled at the memory. “The mothers enjoyed a good rest.”

Our visit to the clinic was the doctor’s first in many years. During his semi-annual pilgrimages to Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, he avoided the scenes of his former life. It was his way of protecting the past. He’d agreed to show me the clinic because the city was changing quickly, and ruins like these were rare now. Somaliland split from the rest of the Somalia in 1991, after a long war of secession, but only now was a shoestring rebuilding project finally gaining momentum.

“This place was on the frontline for an entire month,” he said. Ismail touched one of the bullet holes that pocked the walls, fingering its petals of broken plaster. “The people who were born here live now everywhere in the world.”

Before the war, his practice was popular among the city’s burgeoning middle class, and for nearly a decade, until he fled into exile, eventually settling his own family in Canada, he was one of Somalia’s most successful obstetricians.

We stepped outside. A man with a heavy beard approached. Was he interested in the doctor or me? Ismail was a minor celebrity in this, his hometown—he gave lectures on the local TV channel—but local people had grown used to well-heeled former refugees who now vacationed here. Journalists, foreigners of any kind, were rare. I was here because I wanted to see Africa’s least-known and only homegrown democracy.

The man harangued us with a story about the Somali Army’s wartime massacre of civilians. “In this very place, they stopped a woman with a young child. When they discovered this one was a male, they”—the man began to shout, miming the violent act—“they throw it away into the ground! The lady, she, she, she—”

“You saw this?” asked Ismail.

“She, the lady was, she carry the remainings of her child for three days. Three days!”

“It’s true,” Ismail said, “there was evidence of systematic —”

But the litany continued: “The boys were killed. Babies, women, old men, so many killings. Her relatives were telling me what happened. She went crazy, her baby was dead—”

“Thank you,” the doctor said. He shook the man’s hand. I shook the man’s hand. We walked back to the car. “Twenty years ago that happened,” Ismail said, unlocking the doors. “People, they keep the wounds fresh. Somebody’s story becomes everybody’s story.”

Every July, several thousand former refugees descend upon Somaliland, bringing a certain glamor to the place. SUVs that sit parked in garages most of the year are waxed and polished and toured through the streets. Pretty girls who talk too loudly and wear their hijabs too jauntily wander the markets, clucking at the gaudy stuff on offer. Slouch-bellied men in golf shirts greet their smaller, thinner, shabbier friends, swallowing them with hugs, thumping their backs. Important meetings are held in the ballrooms of the big hotels and new ventures are reported in the local newspapers. Differences of opinion are reported, too, with an undertone of skepticism about the role of returnee politicians and businessmen in the rebuilding of the country. The newspapers that cover Somaliland’s diaspora, of which there are many (one, seemingly, for every enclave around the world: from Toronto to Minneapolis to Washington DC to London; Helsinki and Dubai and Melbourne), gossip about who from their community is shaking things up back home. For a few weeks, anything seems possible, and speculation about Somaliland’s new prospects for international recognition grows bold.

Somaliland’s long and uncertain path to statehood began in the nineteenth century. During the Scramble for Africa, the European powers invaded the Horn of Africa, eventually conquering the Somali people and dismembering their homeland. The British claimed the north, the Italians claimed the south, and the French claimed a marginal territory in the far northeast. British Somaliland, as present-day Somaliland was then known, is a few hundred kilometers of rolling scrubland along the Gulf of Aden, a thin finger of water that separates Africa from the Arabian Peninsula.

The territories were strategically important but resource-poor. Under European rule, the Somalis formulated the ideology of Pan-Somalism, an irredentist movement that sought to reunite the disjoined Somali territories as an ethnic mega-state. And so it was that in 1960, at the beginning of the end of colonial Africa, British Somaliland and Somalia Italia each declared their independence and then merged to form present-day Somalia. It was to be the foundation of an even larger state that would one day incorporate the French territory and parts of Ethiopia and Kenya.

The dream of Greater Somalia was never realized. In 1969, Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, a southerner, staged a military coup and instituted a Communist regime. A halfhearted attempt was made to reconcile Islam, the state religion, with Marxism. Clans—the powerful and often rivalrous family groups that form a cornerstone of traditional Somali politics—were banned outright.

Barre’s ambitions led Somalia into a disastrous war with Ethiopia in 1977. Weakened in defeat, the Barre regime was drawn into clan politics in an attempt to consolidate its power. The northern clans were marginalized, and the Somali National Movement (SNM), a separatist rebel group, grew out of that alienation. In the 1980s, the SNM launched a guerrilla insurgency in northern Somalia, the former territory of British Somaliland, and the Barre regime responded with brutal reprisals—poisoning wells and killing civilians.

Tens of thousands of northerners were killed and hundreds of thousands more displaced in the four-year war of secession that followed. Much of the population in the north, then about three million people, fled to Ethiopia. Several hundred thousand emigrated abroad. At the time, the enormity of the crisis barely registered with the international media. As civil war engulfed the rest of Somalia, the former British protectorate withdrew from the conflict, elected a government, and declared independence as the Republic of Somaliland. The international community provided no help. Aid and expertise were supplied instead by the former refugees who now formed a large and active expatriate population in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.

They were cheerful, dogged utopians who called themselves Somalilanders, without being able to articulate what that meant. Any could tell you exactly how it was that their fledgling republic qualified for statehood, yet none could satisfactorily explain what made them different from Somalis. The very idea that a peaceful, liberal democracy could thrive next to the world’s longest-standing failed state seemed highly improbable.

On the way from Toronto to Hargeisa, I visited the Somaliland Mission in London. During my layover, I rushed to find the office among the fast-food shops and off-licenses along Whitechapel Road, and then, arriving late, struggled to be admitted. Office hours were strictly observed, the secretary explained; no exceptions could be made. After some undignified pleading, I was allowed into the tiny front room, told that visas could not be issued on the spot, and made to wait.

I surveyed the office from a foldout chair. In one corner stood the Somaliland flag, a recent confection that incorporated the Shahadah, the Muslim declaration of the one true god, and a black star that was meant to symbolize the death of Greater Somalia. On the wall above the secretary’s desk was a portrait of the president. Beside me, on what looked like a repurposed bedside table, were strewn old newspapers from Hargeisa. The windows were shut—I assumed to keep out the smell of kebab and fried chicken takeaway. A homemade sign that said visa section marked the consul’s office door. We couldn’t have been further from embassy row.

After a few minutes the gray-haired consul emerged and greeted me with a slow shake of the head. “You must get your visa in Addis Ababa,” he said.

“But I emailed last week,” I replied, trying to sound friendly. I had no plans to linger in the Ethiopian capital. “And I called this morning.”

“It is not possible.” He spoke through clenched, knifelike teeth; gum disease had unsheathed his dental roots.

“But your website says I should apply here.”

“It is not possible,” he said again. “You will need to register with the Ministry of Information when you arrive.” But already the consul was leading me into his office. He retrieved a receipt book and stamp pad from his desk. “I can only accept cash. Pounds sterling or American dollars.”

The bluff had been intended, I suppose, to create the appearance of bureaucracy. The consul couldn’t hide the fact his national Mission in London was a one-man show, and he seemed relieved to be done with the pantomime.

We chatted while my journalist visa printed on the inkjet behind his desk. I offered a provocation: Was Somaliland not better off without international recognition? By most accounts, the breakaway republic was doing well without the benefit of foreign aid. Of course, what Somalilanders emphatically did not want was to become a token African success story, applauded as the way forward for Somalia as a whole. Reunion with the south was the thing people feared most.

The consul looked at me blandly. “That is one way of analyzing the situation,” he said. Then, after a beat, “You should see the zoo in Minister A—’s backyard.”

“Zoo?” I said, trying not to sound diminished by this sudden, astonishing piece of trivia.

“He keeps lions and hyenas. I think he has imported a tiger as well. Ask around. Someone will be able to take you.”

The consul smoothed the visa into my passport with the heel of his fist. “It is an amazing thing, when you think of it.”

I arrived in Hargeisa on a hot, overcast afternoon in mid-July. The city spread in clusters along the bottom of a gray and weedy valley, loomed over by the rounded silhouettes of the Nassa Hablood hills. The city’s defining human features were a corridor of sullen government buildings and the old colonial barracks, which stood on the banks of the glutinous river running through the city’s center. Encampments of patchwork tents grew spontaneously in the empty spaces the war had left behind. They alluded to an older way of life: nomadism, which had now rooted. Newly risen hotels and offices broke the monotony of the khaki cityscape. There was a technical college and a women’s hospital, a couple of new mosques, and, in the subdivisions farther out, rows of bone-white compounds with redand green-tile rooftops. You wouldn’t know that fifteen years ago the city was nearly bereft of people, that twenty years ago it was a smoldering pile of rubble, or that once upon a time this apostate capital was a locus of already doomed Somali nationalism.

During the colonial era, in the 1940s and ’50s, Hargeisa led the double life of a British garrison town and a center of political and intellectual ferment for its Somali citizens. It was here that Somali political theater and music were born and from here that the voice of the pan-Somali independence movement, Radio Somali Hargeisa, first issued its broadcasts. At unification, in 1960, Mogadishu was declared the capital and Hargeisa relegated to second-city status.

The war began in earnest after SNM rebels besieged the city in 1988. In response, the Somali Air Force carpet-bombed Hargeisa, flying mission after mission out of the airport while the army rounded up and massacred fighters and civilians. By the time the rebels pushed President Barre’s forces out, in 1991, sixty or seventy thousand people were dead and the city had been pulverized. The long recovery began. Hargeisa, the breakaway republic’s meager showpiece, was almost entirely rebuilt.

I rode through the blistering heat to the Ministry of Information, where one of the press officers had invited me to tea. Because of some of the things he told me, I won’t reveal his name— but he was an exuberant and unflinching propagandist. Somaliland’s case for statehood was airtight, he said. International recognition was forthcoming—Had I seen this country? How could it not be? And in four years, maximum, Somaliland would take its rightful seat in the United Nations. The press officer was one of those naturally funny, almost compulsively charismatic guys. I couldn’t tell whether he placed his faith in the story he was telling or in his storytelling itself. When I said I doubted the world would recognize Somaliland before there was peace in the rest of Somalia, he looked so disappointed I thought I’d hurt his feelings.

He told a story about a local politician I’ll call Abdulkhadir: “The minister, he was known for the size of his behind. Now, this was not a small behind. It was very big”—here the he cupped his hands and spread them wide and then wider again to make his point—“and you know, Somalis, we like to give nicknames. If my friend Yusuf has an ugly face, we will call him Handsome Yusuf. If my friend has a limp, we will call him, what, Elegant.”

“Wow.”

“Really! So this minister, Abdulkhadir, he has a very large buttock. And around this time the government begins to import Toyotas which have a very large boot. Do you understand what I am saying? The boot is very, how do you say it—”

“Spacious?”

“Spacious. It is very spacious. They say, ‘I like this spacious boot. But, hmm, there is a very obvious similarity between the boot of this car and the buttock of our certain minister. Can you guess how the car is known here? We call it the ‘Abdulkhadir.’ We say, ‘Oh, I think I will drive my Abdulkhadir to the market,’ or ‘Oh, I need to fill my Abdulkhadir with petrol.’”

He laughed and offered me his Abdulkhadir and a listless driver, who slouched behind the wheel in a state of near-unconsciousness as we visited the war memorial, the big hotels, the central mosque, the airport, and the iconic currency market, where traders lounged behind massive bricks of Somaliland shillings and Ethiopian birr. The ministry itself featured one of the best attractions: an old Radio Hargeisa van from which the rebels transmitted separatist propaganda during the war.

The press officer also tried to foist a translator on me, but I already had one. Ahmed Abdi Jama was a nervous, well-meaning man of about fifty, the friend of a friend who had followed the diaspora to Finland. He narrated the tour with a mix of factoids (“Did you know that Hargeisa sits at an elevation of over 1,300 meters above sea level? Or that it was settled in Neolithic times?”), personal history (“Before I moved to Finland …”), and oddly self-thwarting commentary. “You can see it is very good,” he said of the University of Hargeisa, which seemed like a perfectly reasonable institution. “For us. But it is not much compared, for example, to the universities of Finland.”

The most expansive businesses and expensive hotels were either diaspora-owned or silent-partnered by those same entities. These included the national airline, banks, trading companies, gas stations, even market stalls. One of the most prominent expatriate businesses was Dahabshiil, a money wire service which boasted, legitimately, that it could transfer funds from just about anywhere in the world to anywhere in Somaliland, even the remotest village, within twenty-four hours. Thanks to the sheer numbers of those who had left, hundreds of millions of dollars were pumped into the economy through Dahabshiil in the form of these small cash remittances—more than half of the nation’s annual GDP.

The return of the diaspora, however, were a recent phenomenon. Many had supported Somaliland’s recovery from the security of their adopted countries, remitting money home until the situation stabilized. A few veteran politicians and intellectuals were the first to visit from abroad. They helped to negotiate the peace when, in the mid-’90s, a short-lived conflict broke out between rival architects of the breakaway republic. By the turn of the present century, a brave few were spending their holidays here.

Given the relative wealth and power of the returnees compared to full-time national, eventually new tensions were bound to develop. It didn’t take long.

Before retraining as a psychiatrist, before emigrating to North America with his wife and young son, before languishing in an Ethiopian refugee camp, before fleeing Hargeisa on foot and walking across the desert until his feet bled, Dr. Aden Ismail was a prisoner of the Somali Army. He was arrested soon after the destruction of his clinic and forced to patch together wounded soldiers at the army barracks. The rebels had advanced into the city by then, and Hargeisa was the scene of frequent shelling and bombardments. Trapped behind enemy lines, Ismail found himself rooting for the rebels even as he feared that an SNM victory would mean his own inadvertent death.

“I worked almost twenty-four hours every day for ten days. If I stopped they would kill me,” he explained. Somehow—he could barely recall the circumstances, though he remembered walking only at night, to avoid detection—Ismail escaped to one of the SNM outposts, a field hospital near the town of Gedebilay, where he volunteered as a trauma surgeon. He treated civilians and rebel fighters until, after several months, their coordinates were discovered by the Somali Air Force and everyone was forced to flee.

Ismail wanted to emphasize the scope of the war’s psychological toll, how it continued to define Somalilanders, wherever they lived. He used himself as an example. The round, gray suburban doctor I knew was difficult to square with the gaunt refugee in the photograph he showed me. Taken inside an Ethiopian camp, the photo depicted a haggard man seated with a small child, his son. He looks old enough to be the boy’s grandfather, though he is only thirtytwo or thirty-three. Ismail was in the throes of an untreated thyroid disorder then, and troubled by what, as a trainee psychiatrist a few years later, he would come to recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It was easier, he said with typical modesty, to qualify as a psychiatrist than to requalify as an OB-GYN. But that wasn’t the only reason he made the switch. When he moved with his family to the US and then to Canada, Ismail and his wife endured frequent nightmares: terrible, vivid horrorscapes. The sound of an airplane passing overhead could inspire near-paralytic fear, even in the middle of the day. They weren’t alone: many of their friends, other refugees, alluded to similar bouts of anxiety. Ismail and his wife sought counseling, but most people refused psychiatric treatment of any kind. Left untreated PTSD was a problem within the diaspora. The doctor reasoned it would be even worse in Somaliland. He had discovered his second calling.

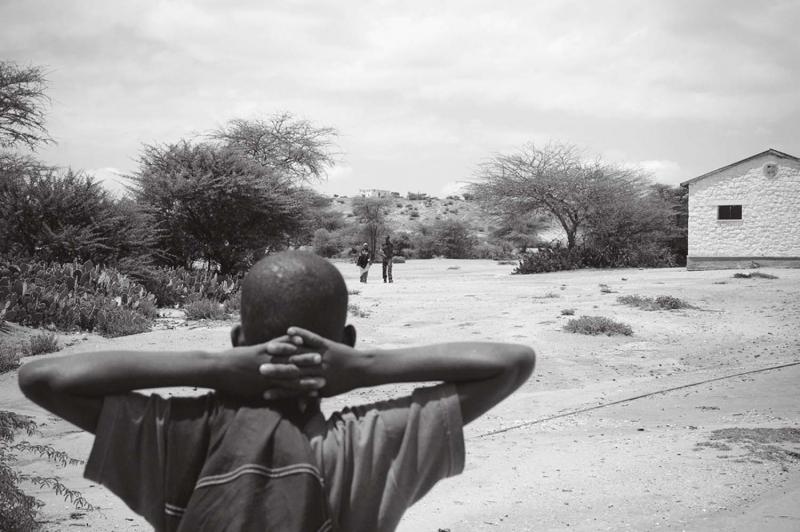

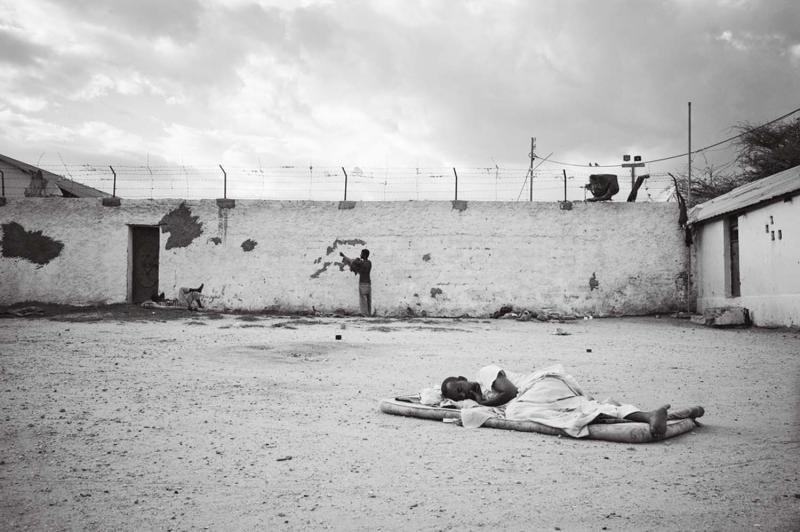

Most summers Ismail flew to Somaliland to donate one month of his time and expertise to Hargeisa General Hospital’s mental health unit. In the afternoons he met with patients, consulted with their families, made diagnoses, prescribed medications. He was keen to show me his work. “You will see the problem,” he said, leading me past spartan offices where staff and patients loitered. The unit occupied a remote corner of the hospital grounds. We walked past a patio where patients slept or sat, sloe-eyed, beneath a high tin roof. They wore sour t-shirts and maccawiis, a traditional wrap favored by Somali men. A young man saluted us and stood at attention until Ismail, grasping his role in the boy’s mistake, ordered him to stand at ease.

“He thinks he’s a rebel fighter. It’s a common delusion. His generation grew up on stories about the war. They fixate,” said Ismail.

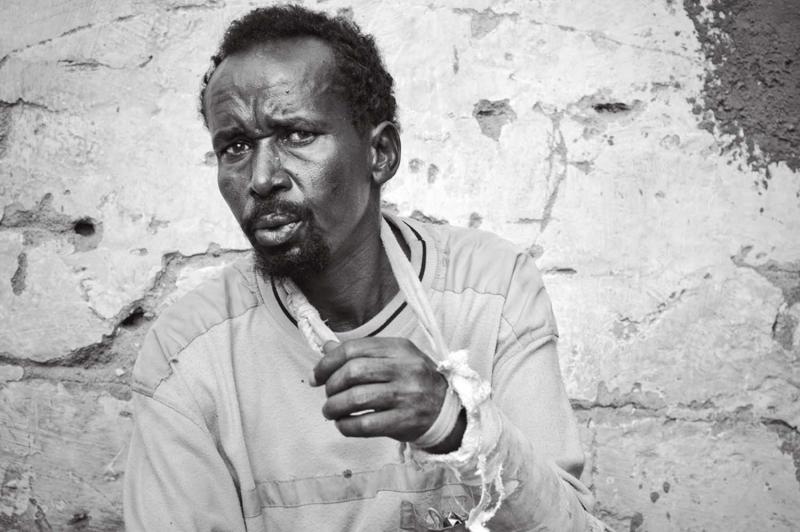

As we approached the dormitory, the atmosphere of benign neglect gave way to an evil smell, a mixture of chemical smoke and human waste. Ash drifted in the air. A patient named Abdillahi was calling for a doctor. He’d set his clothes and bedding alight. The orderlies doused the flames and piled his belongings in a smoldering mass outside. Stuttering and naked, Abdillahi stabbed a hand through the bars of his cell. Ismail shook it. Words spilled from the young man’s mouth in a torrent, as though he’d been waiting his whole life to unburden himself. The doctor interrupted: How long had the CIA been spying on him? Abdillahi wasn’t sure. They talked for awhile, and the man grew calmer. “Probably bipolar,” Ismail said to me. “He believes the American government is persecuting him. I’m told he’s admitted to the hospital every few months.”

Some patients shuffled toward us, their legs chained at the ankles, the chains streaking the dust as the patients’ steps dragged the links toward us.

The psychiatric unit had no doctors; Somaliland has no mental health professionals. None. Most of the time the unit functioned as a repository for the mentally ill and the traumatized rather than as a treatment center. “The families provide the chains, to keep them from escaping,” said Mustaffa, the unit manager.

“When I come here what I am doing is triage,” Ismail said. He expected to see scores of people over the next four weeks, the majority of them outpatients. “A lot of the serious cases that come through here are war veterans, but post-traumatic stress is a problem for everyone.”

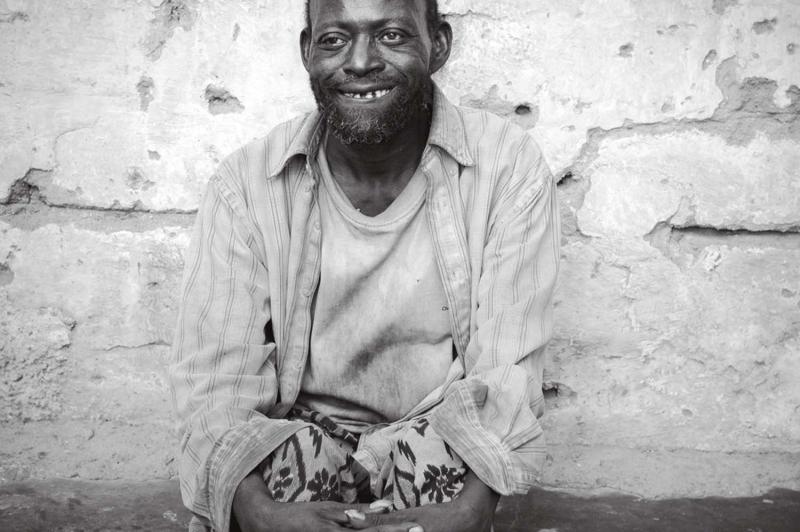

He pointed out a tall, balding man who lingered shyly on the periphery of the patients. The man smiled at us, childishly averting his eyes, gratified by our attention. His mouth was a toothless void.

Ismail continued: “When I first started coming here, what I saw was a lot of acute mental illness, people dealing with severe trauma. Soldiers, widows, mothers who lost children. Now I see more patients complaining of nightmares, insomnia, anger that they cannot explain.” As the situation improved and people returned home from the refugee camps, the long-suppressed trauma of the war bubbled up. By the doctor’s own estimate, more than half of the population, the locals and diaspora population alike, had suffered, or currently were suffering, from PTSD—which is often mistaken for other, better-known mental health issues such as depression and bipolar disorder. Untreated, its effects can linger for years.

“Most will never seek help,” he said. “If they do, they go to a healer. Or they chew khat to make the problem go away.” Somali culture understands mental illness as a sickness of the spirit brought on by outside forces. Traditional healers are sought to exorcize djinns and lift curses. To cure, rather than to manage, illness. The problem is that most patients can’t be cured, and the mental health unit can’t keep them. All but the cases of violent psychopathy are discharged within three months to make room for new admissions.

I sat in on a consultation with an angry man and his nephew who had moved with his family to Marseilles during the war. The man, who had lived all his life in Somaliland, remembered his nephew as a good boy, quiet and polite. As he got older, the boy started smoking marijuana and consorting with “thugs and prostitutes.” He dropped out of school and worked casual jobs, but most of the time he parasitized his family. This was bad enough. Then, about a year ago, the boy grew violent toward his mother and sisters. There were “incidents”—about which the uncle wouldn’t elaborate.

At first the family thought it was a sort of cultural sickness. There’s a word in Somali for people who grew up in the diaspora: dhaqan celis. Its approximate translation is “person without culture,” and it was usually reserved for kids who ran afoul of their parents and were dispatched to Somaliland for cultural rehabilitation. The nephew was sent to live with the uncle and, at first, everything was fine. The boy helped out with the uncle’s business, even made a few friends. Then he discovered khat and everything, the uncle said, went to hell. The boy stayed up for days, chewing and smoking cigarettes. Eventually he began seeing things and talking to himself. Ingested in small doses, khat, a psychotropic plant chewed across the Horn of Africa, has mild amphetamine effects. The leaves induce a sort of euphoric loquacity in the chewer. Sleeplessness and paranoia are common side effects. Chronic consumption can cause psychotic breaks. Its use—and abuse— had increased since the end of the war, which Ismail linked to high unemployment rates and unresolved trauma.

He asked the boy a few questions. Had he experienced hallucinations before trying khat? Did he remember anything of the war? Even these yes-or-no questions were a struggle: the boy had been rendered near-aphasic by chlorpromazine—an old-fashioned antipsychotic, supplied by the World Health Organization and given to Rashid Sheikh Abdillahi, the head of the War Crimes Commission, continues to collect evidence of atrocities committed by Siad Barre’s regime. all new patients. The side effects would have to wear off before Ismail could assess him.

“Khat can act as a trigger for incipient mental illness,” the doctor explained. It was possible, he said, that the boy was headed for a psychotic break and that khat had pushed him over the edge. Or he was simply lashing out. “If that is what happened, then it is a straightforward case of khat psychosis, and he will be fine when he stops chewing.” Ismail proposed to observe the boy for a few days and then report back to the uncle. The old man nodded grimly and left.

The doctor looked tired. “The families expect a cure. They don’t want the stigma of chronic illness.” If what Ismail said about the scope of unresolved trauma was true, if mental health facilities were so scarce, and if the stigma against both mental illness and psychiatry were so strong, what hope did most people actually have?

“Our obsession with recognition, with the international community, I think this is our talking cure,” he mused. “There is so much stigma. We don’t like to talk about what happened to ourselves, so we talk about what happened to other people. We talk about how the world must know us. I don’t know. Maybe it is a symptom. Statehood is a way of talking about the war without talking about the war.”

One afternoon I drove out to the mass graves near the army barracks with Rashid Sheikh Abdillahi, the head of the War Crimes Commission. He stood now at one of the burial sites, on a promontory above the churned-up riverbed where our car got stuck on the way over. His pink shirt and khaki trousers spattered with pale mud.

“It began in May 1998,” he said. “The rainfalls uncovered many skeletons in this area. Maybe one thousand, two thousand people. I can’t say. If we include graves five hundred meters from here, maybe twenty-five hundred total. That was the first time the attention of the people turned to the mass graves and mass killings.”

The commissioner, a stocky man, trod heavily through the scrabbly grass. The graves were unmarked. They dated to the last year of the Somali Army’s occupation of Hargeisa. Abdillahi was using a report by Physicians for Human Rights to guide our walk. “Over there, twelve secondary students were buried at the time of the war,” he said. “The witness was the tractor driver who was forced to dig the grave.”

Not long after the first bones were uncovered, the government of Somaliland invited Physicians for Human Rights to excavate the graves. Their team of forensic scientists determined that systematic killing had indeed taken place. Some of the victims were tied up; nearly all had been shot.

“Why were they killed?” I asked.

“Well, many people were being killed at that time. Mostly civilians, and many soldiers, just because they were from the Isaaq clan.”

Abdillahi pointed to the distant barracks. “Look,” he said. “There was the headquarters of the Somali army. They were taking rows of ten persons bound together, and they were just killing them under that tree. Taking people and killing. There was a kind of ethnic cleansing here.” Abdillahi licked his thumb and rubbed at a spot on his shirt.

There was a time when the survivors of the war wanted only to put the conflict behind them. They had other things to worry about: rebuilding their homes and their neighborhoods, their villages and their cities. As more people, returned from the camps and the diaspora, made those first visits home, there was a push to document the past. The families of the disappeared needed answers and the government wanted evidence of the atrocities that might one day be submitted to the International Criminal Court.

The War Crimes Commission staked out the position that President Barre’s campaign against the people of northern Somalia amounted to ethnic cleansing—or even, they hinted, genocide. This conflation of the notions of clan and ethnicity read like a rhetorical flourish, designed to bolster the case for recognition (on the grounds that Somaliland and Somalia had suffered an irreparable break), but clan identity is just one of the many complexities that beset Somalilanders’ thinking on the question of identity.

If “Somaliland” was a colonial fabrication, “Somalilander” was an utterly modern one. The appellation, with its sonorous proper noun and unwieldy Saxon suffix, is fittingly clunky, bearing as it does the weight of a people’s occupied past and their independent but uncertain future. The term had existed as a sort of catchall for northerners but only really gained a foothold as a political and cultural identity in the aftermath of the war, promoted by the founders of the breakaway republic. They equated clan with ethnicity for the purposes of categorizing the bombardment of Hargeisa as a crime against humanity, but ultimately saw clan as an impediment to statehood. Instead they promoted a national identity that depended on the uncontroversial idea that the Somalis—regardless of clan, regardless of geography—are a single people, and the more controversial notion that the Somalis of the north, because of their shared experiences of trauma and migration—and in spite of their clan differences—could together forge ahead as “Somalilanders.”

And so, with a few stumbles, they had indeed forged ahead. Whether or not they agreed on the definition of the word, the Somalilanders I’d met, almost to a person, believed statehood was their right—and their future.

“Watch!” shouted the war crimes commissioner. “The ground is soft.”

I’d walked out along the promontory for a better look at a gravesite. Abdillahi stopped beside me. “The rain is always moving things. Floods are coming, and every time they are taking away many evidences that shows the atrocities committed by Siad Barre’s regime. This is a problem we are having.”

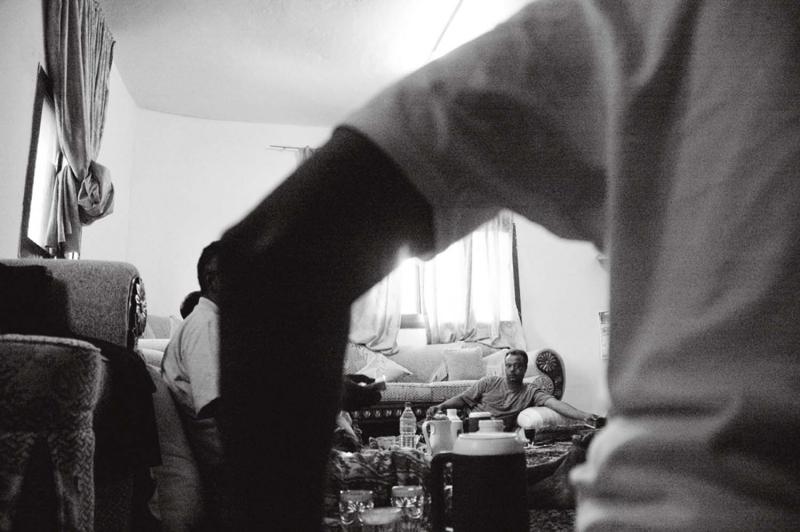

We were on the lookout for khat. My translator, Ahmed Abdi Jama, and his friend Mohamed had invited me to join a khat session. Etiquette dictated that we bring our own supply, plus a gift for our host.

In Somaliland, as in every Somali-speaking region, the leaves are spiritual food and societal glue; my friends told me that to understand the people, the culture, the issues of the day, you had to chew. You could find khat on any street, but Mohamed, who was on a mission to chew as much and as often as he could before returning home to Ohio, was being picky.

“See that one?” he said. Mohamed pointed out a vendor with a khat leaf painted on the side of his cart. It looked like a frill of parsley. He palmed his scalp, teasing with his long fingers the hair that wisped like ash between them. “No good. Old leaves.”

“How can you tell?” I asked. I was keen to try the stuff.

“By the shitty look of his operation.” He pinched his lip and scanned the street.

I contemplated the vendor and his cart and the vendors across the street and their carts. They all looked shitty to me: clumsily painted, with chicken-wire display cases and dirty patio chairs pushed up behind them. The vendors sat alone or with a friend, never more than one, untroubled by the lack of business. They doubled as moneychangers. I had to admit that our guy looked forlorn among them, with his yellowing beard and threadbare djellaba.

The neighborhoods were empty of traffic. A few men, skinny stragglers, their arms still wet from ablutions, hurried along with their bundles. Every afternoon Somaliland turned its back to the world. The ritual began after midday prayers, and by half past twelve the great majority of men could be found gathered in knots under trees, in the backrooms of shops, in the curtain-drawn parlors of friends’ homes. Khat was their muse, opinion their true drug; both were enjoyed lavishly. Politics was the favorite topic. You could expect every man, from the moneychanger to the banker, the laborer to the politician, to have more than a few ideas in his head about how Somaliland should be governed and about how its crisis of recognition should be resolved.

This was the Somali anti-siesta: great effort expended in idleness. We followed the airport road, finally stopping at a vendor Ahmed Abdi Jama knew. The stall looked more permanent than most: three tin walls and a wooden countertop painted yellow. Mohamed was intrigued. “This one they call dirr—it’s cheaper,” he said, digging into the bins. He brandished two identical bundles: “This one is like beer, and this one is like whiskey.”

He insisted on further distinctions between the higher grades of khat. This bundle, with its dusky pink stems and hard, dark leaves, he said,was like a good Scotch. Mellow at first, with a surprising kick. A Glenmorangie, say. There was the question of how Mohamed knew this, for he claimed not to drink, but it went unasked. We settled on a few bundles of lager, with some whisky thrown in for our host.

There were two rooms at the back of the house, with a toilet between them. One was emptied of furniture, bare apart from cushions arrayed on a cheap Persian rug and lit by a long fluorescent bulb. Here a khat session was well underway. The second room was larger. Sofas had been pushed up against three walls and the curtains drawn. Khat and sugary drinks were piled on trays around the room.

Against the fourth wall a wooden bookcase with irregular shelves held photographs of a young family, our host’s. The large, middle-aged man who presided over the room, stretched out whale-like on a pillow, looked nothing like the youth in the pictures. The photos were twentyfive years old, taken in Mogadishu and Hargeisa before the war. As introductions were made I tried and failed to imagine what each man would have looked like before the fighting altered the course of his life.

Hussein was the youngest. He was a local reporter in his late twenties. Mohamed was forty and vague about his profession. The eldest were Ahmed M. and Old Mahmoud, both in their sixties. One was a businessman, the other a retired academic. They embodied the emphatic thinness for which the Somalis are known. A few men had bellies, of a compact roundness that only exaggerated the stringiness of their limbs. They wore golf shirts and macawiis and watches that dripped from their wrists.

I tore eagerly into my stash. Mohamed had already packed his own cheeks with leaves.

“You must take your time,” he said, licking a film of green pulp from the corners of his mouth.

“You will never sleep again,” teased Old Mahmoud. He blew smoke from his nose. The older men seemed to embrace old age as though, having lived through the war, having escaped death, they now shouldered the responsibility of their own demise, which they were bringing about with khat, with cigarettes, with drink. It was to be a slow end: Omar, our host, sipped a can of non-alcoholic beer, the best even a wellconnected man could do in booze-free Somaliland.

Some had never left Somaliland, others lived abroad. Old Mahmoud lived in Saudi Arabia and found Africa pleasantly liberal. Khat was illegal in most countries in the West and the Middle East, so these holidays back home were an occasion to enjoy it. Only Ahmed Abdi Jama refrained from the stuff. “Unlike some of my friends here,” he explained solemnly, “I am around khat every day. There is no in-between. I have to never chew it, or I would chew it all the time.”

Everyone agreed that the country was addicted to khat, and everyone but Hussein agreed it should be banned.

I told my new friends about the cases of khat psychosis I’d seen at Hargeisa Hospital and floated Dr. Ismail’s theory that the spike in its use after the war could be attributed to widespread PTSD.

“Yes!” said Ahmed M.

“What is it, PTSD?” asked Hussein.

Ahmed M., who knew about these sorts of things, took the liberty of explaining.

“Well, I am not sure … I have nightmares,” said Hussein.

“You know it was a genocide here,” said Mohamed.

“What happened in Somaliland, you cannot call it genocide,” said Old Mahmoud.

“It is for the International Criminal Court to decide,” said Hussein.

I packed fresh leaves into my cheek. Once you worked them into a lather, they tasted okay. Good, even. They were bitter, with a peppery undertone, and snapped easily from the branches. I sipped some Coke. The flavor was terrifically complex. I tasted caramel, vanilla, medicinal roots. The khat’s amphetamine effect rolled in on euphoric waves, and I savored everything: the taste of the cola, the throb of the sun behind the curtains, the lucid incoherence of the crosstalk. I really, really liked these people.

“That is why the diaspora is so important,” Ahmed M. was saying. “You can make Somaliland look and smell like a rose, but you need those people who can peddle influence with their governments.”

“The problem,” said Hussein, gravely, “is that we depend too much on them. Somali culture needs to be protected. Somaliland needs to be protected.”

Old Mahmoud agreed. “Socially, we may have problems with people coming with different ways of living.” Someone attempted to light a cigarette backwards, and he laughed. “The problem,” said Ahmed M., “is that we are being held hostage by the situation in Somalia.” His theory, which echoed the theories of most Horn of Africa experts, was that the African Union would never take the necessary first step of recognizing Somaliland’s claim to statehood. Member states like Nigeria, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire—half of the Union, probably—wouldn’t risk emboldening separatist movements within their own borders. The push for statehood needed to come from the international community, from powerful countries like the US and UK. But the risk of lawless Somalia becoming a haven for Islamic terrorism was too great, and Somaliland too geopolitically insignificant, for the big players to make recognition a priority. The State Department would continue to sponsor secular strongmen who could, in theory at least, stabilize Somalia and who would demand reunification with Somaliland. And reunification, Old Mahmoud pointed out, meant another war between north and south.

“War is good,” said Ahmed M., grinning, “as long as it continues only in Somalia. That could be ten, twenty, fifty more years.” There would be time, my friends believed, for the people of Somaliland to figure out what kind of country they wanted, time to change the world’s mind about their case for statehood.

With so much khat to chew and so many ideas to debate, they would need all the time they could get.