Benjamin Rasmussen, twenty-eight, had a far-flung childhood. His family moved to the Philippines within a year of his birth in Baltimore, then boomeranged to the Faroe Islands—his father’s country, a hearty archipelago between Iceland and Denmark—in time for kindergarten. This cultural triptych continued until he finished high school in Manila, at which point he left for Arkansas to study photography.

After college, he moved again to the Faroes, but didn’t have much luck shooting. “I was too immature visually, and too immature in my concept of aesthetic storytelling, to be able to really say anything about the Faroes,” he says. “There was this desperation to photograph like someone trying to create Family of Man pictures. It wasn’t until later that my perspective shifted. It took the ability for me to feel like this was my place in order to photograph it.”

Based in Denver, he returns to the Faroes nearly every summer, when the daylight stretches to twenty hours and the neighbor’s kid might drop by around midnight to play. Summer is the work season, the social season. “The Faroese build relationships in the summer,” he explains. “They have experiences during the summer. The winter is narrative, revisiting those experiences.”

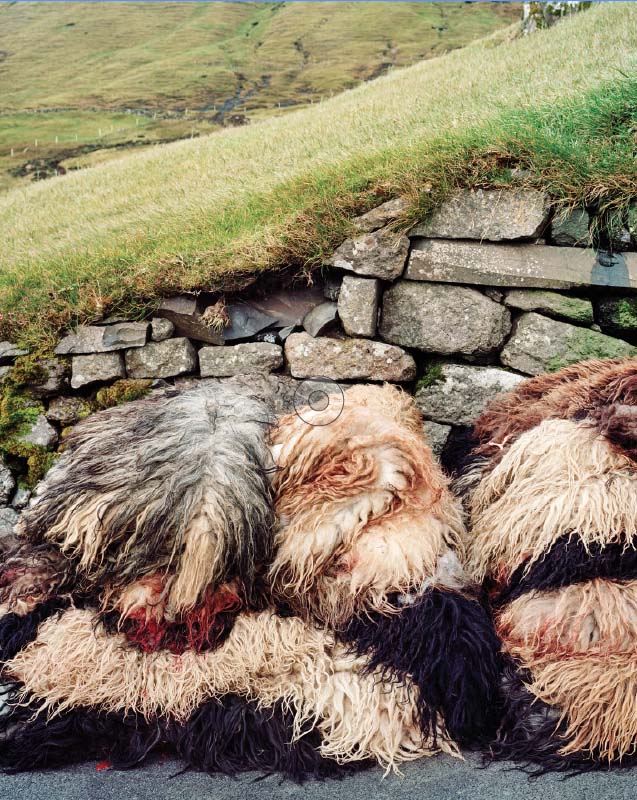

The Faroese are a storytelling people, with ancestries tracing back to Nordic and Irish lines and a history etched in bloody Icelandic sagas. For centuries, fishing has been a pillar of the Faroese livelihood and economy, a profession that keeps fathers, sons, and brothers at sea for nearly a lifetime. “My uncle used to quip that anyone who fished less than three hundred days a year was considered a hobbyist,” Rasmussen says.

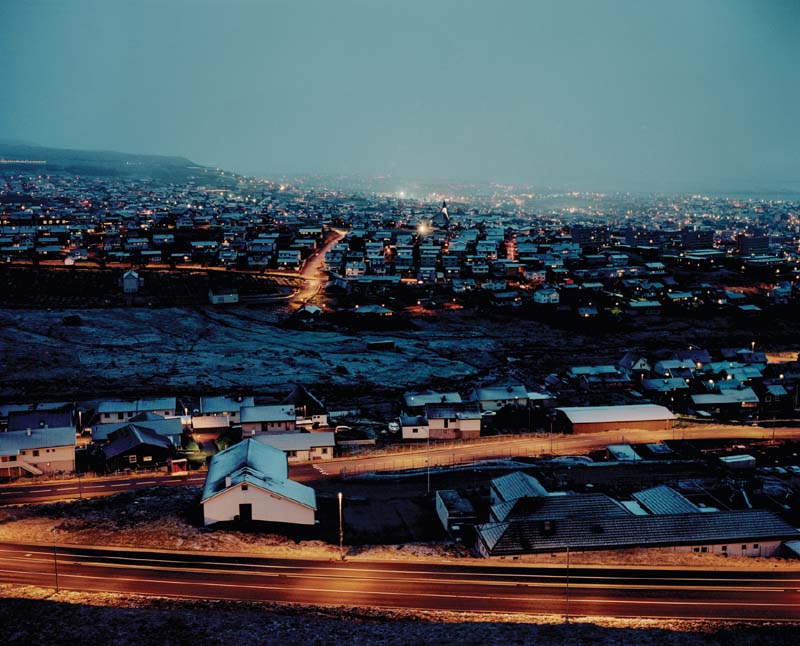

The Faroes became a protectorate of Denmark in the sixteenth century. Just shy of 50,000 people, it enjoys one of the highest minimum wages in the world ($20 USD) and a strong social-welfare system that supports a healthy middle class. This sense of support permeates the culture. “Even if you’re the town drunk,” Rasmussen says, “even if you’re someone who’s slipping through the cracks, it’s such a tight-knit community and network of families that you’re never going to slip through those cracks.”

These small degrees of separation proved vital to his photography. Wary strangers were put at ease when they realized that he’d gone to school with them, or that their grandfathers had worked together, that they had friends in common. His equipment helped, too. He employs a clunky Tachihara 4 5-inch field camera, a reliable icebreaker. “It requires conversation,” he says. “Shooting in large format is at least a ten- to fifteen-minute process, and it looks so ridiculous with the bellows and the shade over your head. It allows people to laugh at me, which puts them at ease and allows me to connect with them.”

Does he worry he might exhaust this subject, given the Faroes’ size and isolation? “Every time I go there to photograph,” he says, “whether it’s the people or the land itself, I just seem to peel off another layer.”

—VQR