The following post is part of our online companion to our Spring 2013 issue on The Business of Literature. Click here for an overview of the issue.

——

When I needed an article from the February 1963 issue of the defunct travel magazine Holiday, I never questioned where to search for it. I picked up the phone and dialed. “Cameron’s,” said the voice on the other end.

Always afraid of saying something stupid and offending the store’s gruff owner, Jeff Frase, I described the item I needed in as few words as possible. In his dry, distant growl, Frase said, “One minute. Let me check.” He sounded annoyed. He put down the phone. When he returned moments later, he said, “Yeah, we have it.” How much? “Five dollars.”

Back in its heyday, big names wrote for Holiday: Steinbeck, Kerouac, Hemingway, Michener. Holiday was the magazine that commissioned E. B. White’s famous 7,500-word essay, “Here Is New York,” in 1948, an essay later published as a best-selling book. It still stands as some of the best prose on one of the world’s most written-about cities.

Five dollars was a bargain. I asked if I could pick up the magazine on Saturday since I worked all week. Frase said, “It’ll be under the counter in the hold box, under your name.”

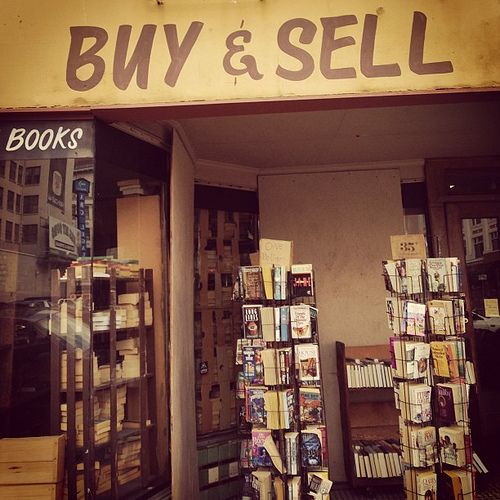

Founded by a stamp collector named Robert Cameron in 1938, Cameron’s Books and Magazines is Portland, Oregon’s oldest used bookstore, and it’s one of the largest vintage magazine dealers in America. Cameron’s might be the largest. When asked for the store’s size, Frase said, “Oh, I don’t know. We could eyeball it, but—” He squinted and leaned forward against the counter. “Maybe forty to eighty foot wide at least, about twice that deep. That’s just the front room. There’s the upstairs.” He waved a finger overhead, tracing the seam where the ceiling meets the south wall. A long passage runs there, its dusty wooden boards lined with mid-century crime, sci-fi, and romance mass markets. He pointed to the room behind him. “And then there’s the magazines.”

How many magazines does he have?

“I really couldn’t say. I just usually tell people ‘Thousands and thousands.’”He stood with his arms crossed behind the cash register. “It’s a real niche market.”

There aren’t many stores left like his. A major one still exists in Skokie, Illinois, on the outskirts of Chicago, called Magazine Museum, formerly calledMagazine Memories in Morton Grove. They have about 140,000 magazines, one from as far back as 1576. “They used to buyfrom me,” Frase said. “If they got an order that they couldn’t fill, they’d buy what I had and sell it to the customers. I’m sure he’s got a website. If not, he’s got a real long—what do you call it—message machine, message on his message machine thing.”

There was a store in Southeast Portland called Periodicals Paradise. They started on Belmont Boulevard, moved to Powell Boulevard, then to Hawthorne Boulevard, and then closed in 2006. They opened up again in a new location in the city’s Hollywood District in 2007,but cut their vintage magazine stock in half. Keeping twenty to forty issues of Life in-store got too expensive. Instead, they started stocking about two issues and keeping the rest in storage.

Cameron’s is what some people call a hole in the wall. To many, it bears all the markings peculiar to the used bookstore species: cramped space, sweet musty smell, stock arranged in an idiosyncratic but functional system that sometimes confuses customers, with codes of conduct on handwritten signs taped to shelves and endcaps. One sign says, “No cell phone cacophony allowed.” Another, written by Frase’s daughter when she was seven, says, “Put away books are happy books.” All of which is to say that Cameron’s offers everything you want in a used bookstore: fair prices, individuality, as well as the books you came for and the books you didn’t expect to find. Very little has changed about Cameron’s over the years, except the luster of the paint. Frase affixes price tags to books by hand and doesn’t manage inventory with a computer.

Despite the rich assortment of general fiction, nonfiction, and vintage paperbacks, it’s the magazines that distinguish the store. Current back-issue titles such as Travel + Leisure and Popular Mechanics are displayed upfront, and a staggering selection of collectible magazines in back. Everything from Life to Look to the Saturday Evening Post, shelved alongside titles you didn’t know or had forgotten existed, such as Argosy, American Boy, and Premiere. Many reside inside protective, plastic sleeves. To access the vintage magazine room, you have to ask permission. “Collier’s magazine?” he’ll say in response to your inquiry. “Yeah, we have a few. Over here.” Then he’ll lead you under a “No Admittance” sign,through a doorway beside the cash register.

As independent bookstores come and go across the country and others become specialized to stay solvent, Cameron’s endures. The question is how. Are vintage magazine collectors numerous enough and sufficiently loose with their money to cover the store’s rent? Who’s buying used and vintage magazines anyway?

On that February day, I was.

I’d called Cameron’s because I was writing an essay about Miles Davis and needed a relevant article I’d spotted in a bibliography. The article was in Holiday. Unlike most modern glossies, Holiday hadn’t been digitized. To access content,I needed the original copy, which made me wonder: with countless titles like The New Yorker digitizing their archives, how did that affect the used magazine market? Do many people visit the store looking for magazines that haven’t been digitized, such as Holiday?

“Not many people ask for Holiday,” Frase said. “It’s only actually until recently that I ever bothered carrying it, because I fell heir to a couple of batches of them and decided to give it a shot. I’ve kind of looked through a couple of them. A lot of times, they’ll devote most of a whole issue to a certain locale—I’ve seen issues on Oregon and San Francisco—so I thought someone potentially might want those. So you put ’em out there and hope someone asks.” I did.

Turns out, I wasn’t the normal vintage magazine customer. Most of Frase’s customers buy vintage magazines as novelties and birthday gifts. They find an issue from around the date of a person’s birth, and mail it to them. They’re what some in the trade call “birthday issues.” These customers are regular people, not a collecting subculture. “And it tends to be sort of middle-class, middle-age, well-dressed people that are just looking,” Frase said, “you know, lookin’ for that gift that they can’t get anywhere else.”

Over the years, he’s learned to spot these customers. “You can tell,” he said. “What they’ll say is, ‘How close can we get to April 14th, 1952?’ or something like that, and then I’ll go check for ’em. First thing I ask is, ‘Is it for a man or a woman?’ because that sort of narrows down what I will show ’em.” Some ask for a particular magazine, like Life or Esquire, for their birthday issue, while others just focus on the issue date.The recipients love it. “Feedback I get, usually, is they love the ads and photos in them, love a lot of the articles, especially if you get someone that was born during the war years.”

The original owner of Cameron’s, Mr. Cameron, didn’t sell magazines. The store’s second owner, Fred Goetz, added the vintage stock in the 1970s. “Just seemed to be a market that no one else was dealing with locally at the time,” Frase said. So Goetz added them to diversify his stock and add another revenue stream. When Goetz hired 30-year-old Frase as a part-time shelving clerk in 1982, he had already built the catwalk and shelving system in the backroom and was filling it with a growing assortment of vintage titles purchased from walk-in customers and estates. So Frase spent the next thirty years growing stock, building more shelves, and discontinuing certain titles while adding others.

Even though it was good business, Goetz’s decision to sell vintage wasn’t entirely financial. “He would pull out a Life magazine almost every lunchtime and spend a few minutes looking through it, then put a little ‘LA’ on the cover in pencil so he knew he’d already looked at that issue.” ‘LA’ stood for ‘looked at.’ He wouldn’t bother erasing the mark when someone bought the magazine. “It was so small it wouldn’t even be noticeable, just noticeable to him.”

Frase read a lot growing up, but he wasn’t a bookish kid, or looking for a career in the book business. He did maintenance work for an apartment management company but was laid off in 1982 during the Reagan recession, when work wasn’t easy to come by. The owner of The King of Rome Bookstore in the Sellwood neighborhood hired him to fill in when he went on vacations. Goetz knew the guy Frase worked for in Sellwood, and Frase managed to parlay that into a recommendation that led to the job at Cameron’s. “By the end of the year,” he said, “Fred needed a manager, and we were getting along, so I just said, ‘Okay, fine.’”

When Mr. Goetz decided to retire in 1989 and sell the store, he gave Frase first crack at coming up with the money. Frase borrowed the down payment from his father and paid it off over ten years. Mr. Goetz continued to work for the store in his retirement, helping with back stock.

***

With more print magazines adding web content than they used to, and some like Newsweek and Spin abandoning print altogether, Frase has noticed a dip in modern used magazine sales. He would usually sell recent magazine issues within a month or two, but no longer. “Certain titles—there’s just no interest in it. That would be for things like Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal, old-time, mainstream titles,” he said. “Once a lot of titles are off the [news]stands, I don’t need to keep buying ’em. I usually have sufficient quantities.”

Some magazines are more resilient than others. “Vogue seems to be about as big as it ever was. Fashion magazines,” he said, “there’s still demand for those.” Rolling Stone vintage copies are still one of his top-sellers out front. And, even though it’s a magazine that many people discuss based on how far behind they are on their reading, used New Yorkers still sell well. “You never know what will sell and what won’t, but rock musicians tend to do pretty well. Of course, I can always sell Marilyn Monroe stuff out there, certain baseball covers, sports heroes, and movie stars.”

To make the collectible magazine trade profitable, Frase employs specific strategies. The most important is depth. He has to stock many weeks and years for a particular title; a couple hundred issues isn’t enough. It has to be decades’ worth. Frase keeps track of his Life magazine stock with a cover guide that he tore out of one of the magazine in the ’80s and laminated. When he sells an issue, he puts a mark through the cover with a grease pencil. That way he knows which issue to replace. “It’s crude but effective.” Life magazine published weekly, which means lots of issues to monitor. The only other titles where he tracks the issues are Playboy and National Geographic.

Recently, Frase has noticed women in their early twenties to thirties buying vintage Playboy as gifts for their boyfriends. He said that never used to happen, but added, “If you get ’em back to the ’70s, there’s a certain quaintness to them.”

Another magazine that has proven popular is Fortune from the 1930s and 1940s, which was a big magazine, square-bound, almost more of a large softcover book. “It was a gorgeous magazine back then. It cost a dollar when everything else cost a dime. There’s a lot of nice color lithographs and offset in it. All it took was one or two people interested, and they pretty much wiped me out. I’ve never ever been able to replace them.” Issues from the 1930s sometimes featured unusual tip-ins (materials inserted in between pages), such as fishermen flies and cigar bands. One issue had a double foldout of a German zeppelin that Frase sold for $75.

One of the most sought-after vintage magazines he stocks is a 1962 issue of Life. In it, the subscription card runs through the center binding, and comes out the other end as a double-sided baseball card. One side is Roger Maris, the other Mickey Mantle. It easily sells for a hundred dollars. And, in one of the biggest recent windfalls for Cameron’s, a forty-year-old man visited from British Columbia. He was looking primarily for 1920s and 1930s Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, with the intent to scan the covers for an online archive. He spent about three thousand dollars in one visit.

Although he doesn’t market aggressively or have more than a modest web presence, Frase isn’t a Luddite. He has a laptop and cell phone. He uses e-mail. If he finds an op-ed in The Oregonian by a writer he likes and the piece is only available online, he’ll read it. He’s just not interested in using a Nook or Kindle. Someone came into the store once and tried to sell him a device.

“It was probably hot,” Frase said. He laughed at the thought of it. “Tried to sell me one, like, ‘What good would that do me?’ He didn’t really have an answer, just thought I would want one because I was a bookstore, but I told him to get out, in so many words. No, wait. I didn’t tell him to get out. I said, ‘Get that thing outta here.’” An unfiltered giddiness infused his laugher. “I mean, people come in and use them, and I don’t make snarky comments or anything like that. I’m sort of live and let live. But, you know, you hear a lot of stuff like, ‘I got a Kindle, but I still prefer the real thing.’ I just say, ‘Well, that’s good.’ I imagine I could come up with a few pretty snarky comments, but I hold my tongue. It doesn’t do ya’ any good to alienate anybody. If you can help it.”

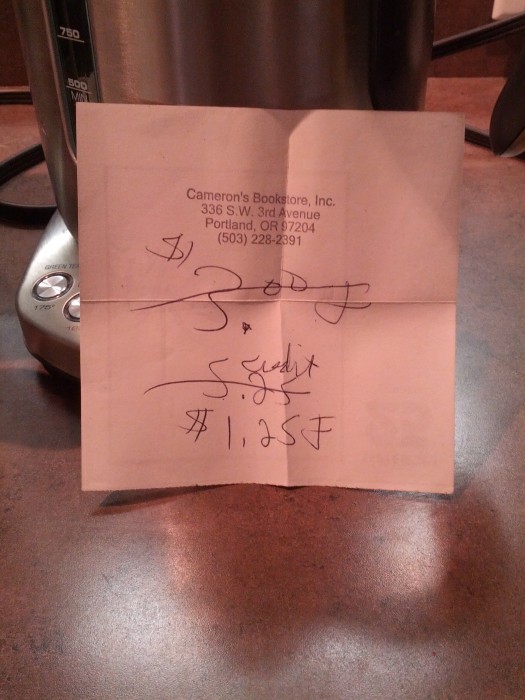

Recently, I sold Jeff Frase some new issues of The New Yorker, The Economist and Travel + Leisure. He gave me three dollars in store credit. He used the edge of the counter to tear off a square of paper and scribbled “$3.00 credit” on it. I used it for a 1973 copy of Esquire, the 40th Anniversary Issue. I didn’t know I wanted it until I found it on the back shelf. The painting on its gatefold cover functions as a literary who’s-who of the era, albeit the typical literary boy’s club: Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, Nora Ephron, John Cheever, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Dorothy Parker, Philip Roth, Gay Talese, both Tom and Thomas Wolfe, John Updike, Saul Bellow, James Baldwin, Vladimir Nabokov, John Steinbeck, and Sinclair Lewis. The yellowing sticker on its cover was addressed to a subscriber named G H Sisson in Burlingame, California. The cover price: $2. I paid $7.50. Another bargain.

I’d also tried to sell Frase recent back issues of literary journals, but he said that, with the exception of Granta and Tin House, they don’t sell. Looking at the early issues of Glimmer Train and copies of defunct titles like Story, I could see he was right. “They just sit,” he said, “mostly forever.” With shelf space at such a premium, Frase has to allocate space to items with a better turnover. Ezra Pound said that literature is the news that stays news, yet despite the durability of literary magazines’ poems and stories, Rolling Stone and Post do better here.

While I browsed a shelf of used literary journals, Jeff answered a call from a man he seemed to know. They talked about magazines. The man was searching for one of a particular vintage, but Jeff didn’t have it in stock. “Yeah,” Jeff said, his voice pained. “Well, it comes through sometimes, but not much. No, not very much. Things like Argosy and that, yeah.” Through a gap in the makeshift shelves I saw him adjust his position behind the counter and uncross his arms. “I got a box of ’em that I drag out for people that are interested,” he told the man on the phone. “Nineteen fifties are five dollars, forties are seven fifty, thirties are ten.”

I sat on the floor and flipped through old issues of Ploughshares and Story, but didn’t buy any.

After a pause, Jeff groaned and tilted his head. “Yeah, there might be one back there, but I can’t check. Normally I would, but today I got something to do so I have to split right at six. We close at six, but normally I would.” The caller then asked about Jeff’s daughter, and the timber of his voice brightened. “She’s great,” he said. “A freshman. Older, like us.” He paused, listening to something the caller was telling him, then he said, “You know, I was just thinking about that the other night. It does fly by. It sure does.”

Photo by Aaron Gilbreath

Explore a few of the last remaining vintage magazine shops:

Magazine Museum

4906 W. Oakton

Skokie, IL

Periodicals Paradise

1924 NE 40th Ave

Portland, OR

Shake Rattle & Read

4812 N Broadway St.

Chicago, IL

——

About the author: Aaron Gilbreath (@AaronGilbreath) has written essays for The New York Times, Kenyon Review, Paris Review, Tin House, AGNI, Black Warrior Review, Brick, The Threepenny Review, Gettysburg Review and Hotel Amerika, and articles for Oxford American, Yeti and The Awl. He sells tea in Portland, Oregon. Visit him online.