“Picture books,” children call them—but they’re not just for children anymore. Literature for adults has lately put words together with images in all sorts of ways, and in places no one would call the radical fringe. The 2010 bestseller and 2011 Pulitzer Prize winner, Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, featured a crucial chapter in the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Yet while Goon Squad may offer the most salient example, it’s hardly the only one—think Shelly Jackson’s Patchwork Girl and Steve Tomasula’s VAS. And in a storytelling form driven by images, one finds ever greater traces of the literary: Comic books have become graphic novels. The overwhelming case in point would be another Pulitzer winner, Art Speigelman’s Maus, but again many others might be cited, including Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.

Back in the 1960s, Donald Barthelme liked to remark that collage was the “art form of the twentieth century,” but combining text and visuals has proven even more congenial with the twenty-first. Two of the latest examples, literary artifacts that depend nonetheless on pictures and design, prove flexible and provocative. Better yet—better for the health of both arts—the novel Bats of the Republic, by Zachary Thomas Dodson, and the nonfiction War Is Beautiful, by David Shields, each prove excellent in their way.

Bats of the Republic is Dodson’s big-press debut, but it’s far from the first book on which he left his mark. Ten years ago he helped found featherproof books, with a mission statement calling for “strange and beautiful” books, including “post-, trans-, and intergenre.” The house’s most celebrated work, Blake Butler’s Scorch Atlas, had a discolored cover and pages that suggested a pocket guide that had, indeed, gone through a fire. Dodson himself authored another of the press’s books, under a cheeky title: boring boring boring boring boring… The text married grainy photos of the punk-rock crowd to exquisite Gothic lettering, and the results won a design award. But the real surprise may have been that boring boring delivered a story. It set up a rocky love affair and then threatened the duo with Hitchcock-style Macguffins. Clearly Dodson grasped that his book couldn’t actually be boring-boring, and that this thing called a “novel” remains inextricably entangled with narrative.

Bats of the Republic is Dodson’s big-press debut, but it’s far from the first book on which he left his mark. Ten years ago he helped found featherproof books, with a mission statement calling for “strange and beautiful” books, including “post-, trans-, and intergenre.” The house’s most celebrated work, Blake Butler’s Scorch Atlas, had a discolored cover and pages that suggested a pocket guide that had, indeed, gone through a fire. Dodson himself authored another of the press’s books, under a cheeky title: boring boring boring boring boring… The text married grainy photos of the punk-rock crowd to exquisite Gothic lettering, and the results won a design award. But the real surprise may have been that boring boring delivered a story. It set up a rocky love affair and then threatened the duo with Hitchcock-style Macguffins. Clearly Dodson grasped that his book couldn’t actually be boring-boring, and that this thing called a “novel” remains inextricably entangled with narrative.

As for the new Bats of the Republic, running approximately 450 pages, its visual elements are certainly ravishing. Credit is due in part to Doubleday, taking on the costs of maps and illustrations, three distinct page colors, foldouts, alternative fonts, and more. Yet anyone who goes beyond mere looking to actual reading will find themselves caught up in the story. I’d go so far as to say the old chestnut “ripping yarn” ought to come out of mothballs—especially since half of what goes on deploys the language and attitudes of the nineteenth century.

Three hundred years apart, in 1843 and 2143, two pairs of lovers endure weirdly similar struggles for identity and wholeness: That’s the migration route of Bats. The character list alone, opening the novel with twinned chutes-and-ladders designs, underscores the parallels between time-settings. In the earlier era, the storm-tossed pair is Zadock and Elswyth, in the later one, Zeke and Eliza. On the list, both men bear the family name Thomas (as for the echo of the author’s name, I’ll get to that); so too, before long, the women turn out to have the same last name.

The mystery of Eliza’s and Elswyth’s parenting is only one among several. Nineteenth-century events primarily track Zadock’s mission into the wilderness—political as well as natural—of the short-lived “Texas Republic,” while the bereft Elswyth, back in Chicago, faces unhappy choices: become wife to a scoundrel or novice in a coven of “Auspices.” Somehow these witchlike seers survive three centuries, and they offer one of the few ways out to the latter-day Eliza, herself between a rock and a hard place, because her Zeke seeks to escape a new Texas “city-state,” part of a vulnerable “National Alliance,” post-“Collapse.”

Throughout, the effect remains chutes and ladders, and gets the adrenaline racing. Likewise bracing is the way Dodson modulates both older and newer English, neither especially ornate. The early ZT writes Elswyth, using an antique synonym for “cool”: “I felt flash with the silver sabre cracking my shins.” The later ZT gets a warning from Eliza’s father: “How do you live with watchposts at every intersection? It is a forest of echoes.” Echoes, indeed: Others resonate between the multiple cultures of the early American Southwest and the struggles for power in the “Alliance.”

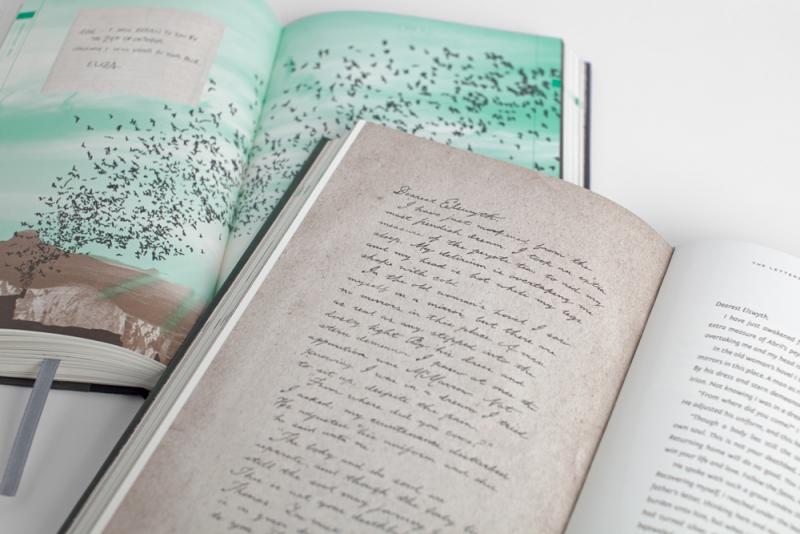

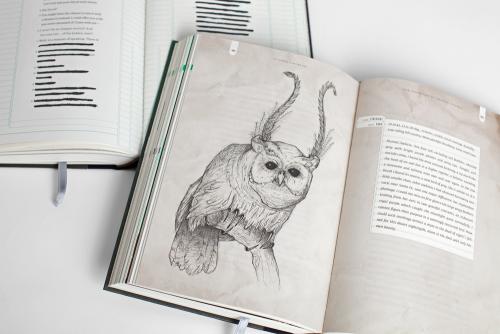

In this hall of mirrors, lost Zadock emerges as the most sympathetic figure, and after him lonesome Eliza. Still, what Dodson is up to has less to do with character than with representing whatever might be termed “reality.” In each of the worlds of Bats, solutions may reside in secret documents, in particular a letter labeled “DO NOT OPEN” and these under-the-table missives feature all sorts of formatting tricks. But then, tricks and tics turn up on almost every page here, and in the book-within-a-book (a roman à clef of course). The great majority of these visual gimmicks contribute to the plot as well. Zadock’s sketches of wilderness animals—drawn by hand and attached to letters themselves in manuscript—start with actual fauna like the jackrabbit and then, as events grow more fantastic, move on to imaginary beasts like the “Stag-Ear Bat.” So too, Dodsonunderscores his mediation of the actual with sly allusions to the principal mediator, namely, himself. The names of the leading men are the most obvious case; also, their pictures suggest his author photo, with his glasses and mustache. Such self-reflexive fiction, overall, can’t help but recall John Barth, in particular his neglected masterpiece Letters (1979). Dodson’s project feels more frolicsome, more accessible, but it raises the same serious question: how know the world?

In this hall of mirrors, lost Zadock emerges as the most sympathetic figure, and after him lonesome Eliza. Still, what Dodson is up to has less to do with character than with representing whatever might be termed “reality.” In each of the worlds of Bats, solutions may reside in secret documents, in particular a letter labeled “DO NOT OPEN” and these under-the-table missives feature all sorts of formatting tricks. But then, tricks and tics turn up on almost every page here, and in the book-within-a-book (a roman à clef of course). The great majority of these visual gimmicks contribute to the plot as well. Zadock’s sketches of wilderness animals—drawn by hand and attached to letters themselves in manuscript—start with actual fauna like the jackrabbit and then, as events grow more fantastic, move on to imaginary beasts like the “Stag-Ear Bat.” So too, Dodsonunderscores his mediation of the actual with sly allusions to the principal mediator, namely, himself. The names of the leading men are the most obvious case; also, their pictures suggest his author photo, with his glasses and mustache. Such self-reflexive fiction, overall, can’t help but recall John Barth, in particular his neglected masterpiece Letters (1979). Dodson’s project feels more frolicsome, more accessible, but it raises the same serious question: how know the world?

David Shields has been worrying over that bone a while now. Back in the 1980s, he first was published as a straightforward novelist, but in 2010 he achieved international fame, not to say notoriety, with Reality Hunger. This book-length “manifesto” intended to yank down the towering idol of The Author—a lousy conduit, according to Shields, for the human experience. As he put it in one often-cited passage: “Story seems to say that everything happens for a reason, and I want to say, No, it doesn’t.” In opposition to the manipulations of story and author, he held up the honesty of collage, with its manic, magpie appropriations. Therefore he had the temerity to make Hunger its own best example, using other writers’ words for almost half the hundreds of shards of prose the book brought together. The threat of lawsuit forced the publisher to add a few closing pages of citations, but these began with Shields’s own recommendation that readers scissor out the offending list.

David Shields has been worrying over that bone a while now. Back in the 1980s, he first was published as a straightforward novelist, but in 2010 he achieved international fame, not to say notoriety, with Reality Hunger. This book-length “manifesto” intended to yank down the towering idol of The Author—a lousy conduit, according to Shields, for the human experience. As he put it in one often-cited passage: “Story seems to say that everything happens for a reason, and I want to say, No, it doesn’t.” In opposition to the manipulations of story and author, he held up the honesty of collage, with its manic, magpie appropriations. Therefore he had the temerity to make Hunger its own best example, using other writers’ words for almost half the hundreds of shards of prose the book brought together. The threat of lawsuit forced the publisher to add a few closing pages of citations, but these began with Shields’s own recommendation that readers scissor out the offending list.

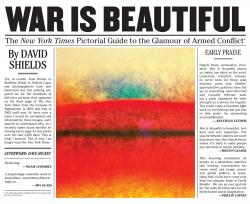

This collaborative aesthetic has also fueled recent work like I Think You’re Totally Wrong (2015), a joshing “quarrel” with a former student, and, especially, the new, more earnest effort War Is Beautiful.The text may be slender, but it startles you nonetheless with how little it includes by the nominal author. Shields puts his name on nothing except the cover and an “Introduction” of just three pages—themselves buffered by a good deal of white space. In them, he wastes no time getting to the insight that drove him to compile this text:

For decades, upon opening The New York Times every morning and contemplating the front page, I was entranced by the war photographs. My attraction…evolved into a mixture of rapture, bafflement, and repulsion. Over time I realized that these photos glorified war through an unrelenting parade a beautiful images.

Shields backs up his contentious stance right away. Referencing a highly regarded history of the Times, he first sketches the paper’s longstanding chummy relationship to whatever administration holds control in Washington. After that he cites contemporary sources, in particular the Iraqi photojournalist Farah Nosh, who corroborate his claim that the Times tried not just to report the facts of the hostilities in the Middle East, but to shape their perception in the US. Finally, he breaks down that shaping into ten categories of photographs that “repeat certain visual tropes” in order to idealize the destruction being wrought abroad. These he designates with stark single-word names, such as “Playground” and “Pietà.”

With that the author yields the stage: the page. Foremost among his collaborators is the arts writer Dave Hickey, whose closing remarks, “War Is Beautiful, They Said,” begin on the back of the dust jacket. Hickey adds useful comparisons to earlier war photography, and a stiff shot of grim wit, but his material runs no longer than the introduction. Any other words in War (not counting the photo credits, to be sure) are of two kinds. The most significant would seem to be the epigraphs that introduce each of the sets of photographs, the ten “chapters” that, one by one, represent Shields’s categories. The introductory lines are taken from lesser-known journalists and historians, but also from the likes of Cormac McCarthy, who turns up before two of the sets, his prose ringing like Isaiah. There’s also the acerbic Gore Vidal: “The New York Times, the Typhoid Mary of American journalism.” Yet what may be more interesting, and what definitely occupy more space, are the blurbs. I count twenty-three all told, plastered over the dust jacket fore and aft, all in the same font and size as the work from Shields and Hickey. Endorsements run the gamut from mighty names like Noam Chomsky to those only a scholar would recognize. The cumulative effect is another challenge to what matters in literature, and another reminder of how easily our opinions are swayed.

With that the author yields the stage: the page. Foremost among his collaborators is the arts writer Dave Hickey, whose closing remarks, “War Is Beautiful, They Said,” begin on the back of the dust jacket. Hickey adds useful comparisons to earlier war photography, and a stiff shot of grim wit, but his material runs no longer than the introduction. Any other words in War (not counting the photo credits, to be sure) are of two kinds. The most significant would seem to be the epigraphs that introduce each of the sets of photographs, the ten “chapters” that, one by one, represent Shields’s categories. The introductory lines are taken from lesser-known journalists and historians, but also from the likes of Cormac McCarthy, who turns up before two of the sets, his prose ringing like Isaiah. There’s also the acerbic Gore Vidal: “The New York Times, the Typhoid Mary of American journalism.” Yet what may be more interesting, and what definitely occupy more space, are the blurbs. I count twenty-three all told, plastered over the dust jacket fore and aft, all in the same font and size as the work from Shields and Hickey. Endorsements run the gamut from mighty names like Noam Chomsky to those only a scholar would recognize. The cumulative effect is another challenge to what matters in literature, and another reminder of how easily our opinions are swayed.

Ultimately, though, the elements that matter most in this collage are the photographs. Each has been culled from page one of the Times, reproduced in full color and occupying a single page. As we look through these, still more nettling questions crowd the mind, concerning both the bloody subject and the breathtaking text. For isn’t this a coffee-table book? A conversation piece? Wider than it is tall, the dominant colors of its jacket that powerful triad of red, white, and black, the cover layout a comforting imitation of our “paper of record”—this War isindeed beautiful. It casts a witch’s spell, by which Shields pulls off a diabolic metamorphosis. He’s made a monster, one we all must get to know, of that kinder, gentler creature, the “picture book.”