About once a year, I reread Dracula, an act which, were I to stop with that book alone, would make its author, Bram Stoker, disheartened, I suspect. A tick more than 100 years after Stoker’s death, Dracula endures for a host of reasons: the visage of terror at the core of its narrative, the scope of its plot, and its mélange of styles. Romance, mystery, potboiler, penny dreadful, medical casebook, travelogue, it all goes into the soup of Stoker’s most famous work in a way that is, we would believe, dissimilar from the rest of his writings, which have failed to gain Dracula’s eternal life. Stoker would have insisted that this perception should not be the case, that he was not some “one-hit wonder,” a literary version of one of those bands whose name you can’t remember who nonetheless has its lone chart-topper play on the oldies station constantly.

About once a year, I reread Dracula, an act which, were I to stop with that book alone, would make its author, Bram Stoker, disheartened, I suspect. A tick more than 100 years after Stoker’s death, Dracula endures for a host of reasons: the visage of terror at the core of its narrative, the scope of its plot, and its mélange of styles. Romance, mystery, potboiler, penny dreadful, medical casebook, travelogue, it all goes into the soup of Stoker’s most famous work in a way that is, we would believe, dissimilar from the rest of his writings, which have failed to gain Dracula’s eternal life. Stoker would have insisted that this perception should not be the case, that he was not some “one-hit wonder,” a literary version of one of those bands whose name you can’t remember who nonetheless has its lone chart-topper play on the oldies station constantly.

Dracula remains ubiquitous and has gone into enough sundry forms since its 1897 publication that many a Twilight buff has probably never even heard of Stoker at this juncture. Stoker, though, regarded the novel as another of his well-crafted, well-researched books, a successful work at the level of language and story.

But despite Dracula’s success and endurance, Stoker’s other works are unknown to just about any reader who has taken the time to travel to Transylvania with poor Jonathan Harker. If you’ve read any other Stoker, it’s probably The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), a tale of archaeology gone way wrong. Or maybe you have read The Lair of the White Worm (1911), which is truly twisted—enough so that Ken Russell made it into a god-awful 1988 movie starring Hugh Grant—and does feature an actual giant white worm, a creature which somehow manages to be a secondary villain. “Dracula’s Guest,” a short story that appeared posthumously in 1914, gets some attention, mostly on the conjecture that it’s the excised first chapter of its novelistic counterpart, even though Stoker intended it as a stand-alone work.

Stoker’s ascent to Dracula was not a steep one, but must have seemed a shock to those who knew him. Born in Dublin, in 1847, Stoker was bedridden for much of his early life. He attended Trinity College, developed an interest in the theater, married a former paramour of Oscar Wilde (to Wilde’s irritation), began writing theater reviews, and moved to London, where he became the manager of the actor Henry Irving’s Lyceum Theatre, a job that was both time-consuming and energy-draining. On the side, he wrote. His first novel, The Primrose Path, appeared in 1875. There would be three more before the appearance of Dracula in 1897.

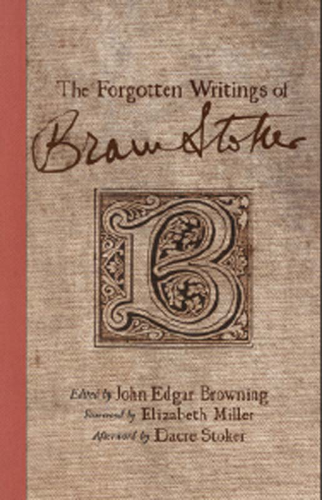

Stoker almost always wrote well, and did so in a manner that confounds the expectations of today’s readers. Simply put, he was never as much about the macabre as we think. What has been too little considered is that Stoker imbued his work with a sly humor that managed to evince both piquancy and charm, a rare blend, even though, from a putative standpoint, we’re supposedly here for horror. And if you’re reading Stoker’s oeuvre—including Dracula— mostly for chills and thrills, you might come away feeling like you’ve been cheated somewhat, that the boogeyman has not been sufficiently macabre to earn his title. But as the doggedly assembled The Forgotten Writings of Bram Stoker (2012) attests, Stoker the writer would be far better served if readers made a point of reading his work on its terms, rather than on their own. An important volume in Stoker scholarship—with writings that have mostly (or perhaps entirely, in some cases) gone unseen since the time of their original publication—the core lesson is this: Leave the boogeyman in the closet. Should he come out, he comes out; otherwise, let’s be mindful of the threat of him while we’re busy exploring other worlds—and the literary means of conveyance through them.

The other factor working against Stoker is what I hold as one of his key strengths: the Modernistic element to his writing. There is a lot less of what we think of as truly Gothic (even in Dracula) than we’ve come to expect. This is collage art, with a panoply of voices, from a panoply of sources, cobbled into a whole. The narrative is anything but linear, and from horror comes humor, as though extreme emotions birth their opposite, a very Modernistic conceit. (Any James Joyce fan, meanwhile, would do well to read the conversations of Mr. Swales in Dracula and compare them with any of a number of voices in Ulysses, to get a sense of how well one Modernist read another proto-Modernist.) The man who largely invented what we think of as the rules of being a vampire has no problem providing a cutaway to the nefarious Dracula busy making Harker’s bed, sunlight streaming through the window, like he works at the local Econo Lodge.

Stoker’s writings are still being discovered, and skilled literary detective work went into finding everything in The Forgotten Writings. There is a range of material, which is appropriate, given that Stoker was sufficiently industrious that he bounded from one form—and job—to another, penning criticism, the aforesaid novels, short stories, and a seemingly endless stream of mash notes for his longtime boss, the aforementioned Irving.

Stoker certainly could shill, and that’s what we find him doing for Irving in a number of pieces toward the back of this anthology. But what we’re really here for is the fiction and, to a lesser extent, the journalistic writing, with each revealing something about the other, which underscores what makes Stoker’s art unclassifiable, and perhaps explains why he is under-read: There’s no easy category to dump him in, and the one he’s in—Scary Writer Guy—

is limiting.

Stoker does twisted well, and it’s when we often find him at his most amusing, albeit in a disturbing fashion, which ups the piquancy and makes the lucky reader who ventures into this arena feel like he or she is in on something that few people know about, and many more should. One wishes to tell others what one has just experienced, so that they can, too. So now I shall tell you about “Old Hoggen: A Mystery.”

To my thinking, Stoker never wrote anything finer than this 1893 short story. A man named Augustus lives with his wife, his mother-in-law, and the mother-in-law’s cousin. The latter two have a constant hankering for crabs, and our put-upon Augustus is told to go out and secure some from the sea. They have newly moved to their coastal town, where an elderly and horrible but oddly beloved miser (Old Hoggen) has lately disappeared. The new family is strongly suspected of doing the old brute in, and the workers of the town—or people impersonating workers—make all manner of excuse to come around the house and take measurements to see if there was room to bury all of Hoggen’s loot. It’s a whimsical, surrealistic joke, with the rapid-fire wit of the Marx Brothers. A man selling fish turns up with a sad, solitary sole; Augustus purchases it, and the seller heads out to the backyard, ostensibly to clean the fish. Instead, he takes to measuring.

I asked him what the dickens he was doing there still, and why he was measuring. He answered vaguely that he was not measuring.

“Why, man alive,” said I, “don’t tell me such a story—I saw you at it—why, you are doing it still,” as indeed he was.

He stood up and answered me: “Well, sir, I will tell you why. I was looking to see if I could find room to bury the skin of the sole.”

He had not skinned the sole, which lay on a flag in the hot sunshine, and was beginning to look glassy.

This is Stoker at the apex of his writing. It’s a piss take, in the classic British sense, but there’s something mordant at play, too. Stoker knew—as did Samuel Beckett—as did Oliver Hardy, for that matter—that there is great humor to be sourced from exasperation.

Augustus makes it to the sea, where he comes upon a body floating in the water—that of Old Hoggen. Two crabs tumble out of the corpse, and into Augustus’s pockets they go to appease—and extract some revenge on—his pushy in-laws. But in an attempt to drag the corpse to the authorities, it begins to fall apart, piece by piece, until only the head remains, which is lost when Augustus tumbles into quicksand. He manages to free himself, only to end up in the clutches of a policeman and a coastguardsman who debate whether to kill him after they’ve taken the bank notes (that had been in Old Hoggen’s clothes) which Augustus was attempting to turn in. It’s a scene straight out of Flann O’Brien, and the corrupt duo reemerge in doppelgänger form at Augustus’s house. There are temporal shifts, and yet it’s all set in the tone of a mock travelogue, one of those “how I spent my summer” essays that kids write. A mystery? Well, yes, in a sense. But not in the classic mystery sense. And not a farce either. “Old Hoggen” is nothing less than its own thing.

The same can’t quite be said for “When the Sky Rains Gold” (1894), a sort of mock fairy tale which sets up a conceit—a fair maiden cannot marry, unless—you guessed it—gold rains from the sky, and the ground becomes encrusted in silver. This will be brought about, of course. The story feels somewhat like a Doctor Who script, albeit one couched in Victorian romantic tropes, but our sense is of an interloper playing about with a form not normally his own, making serrations in it, leaving his, as it were, brand.

Stoker loved physiognomy: You can read people’s insides from his descriptions of their outsides. That technique is deployed constantly throughout Dracula. We see a very Dracula-esque passage here when the maiden’s mouth is described as being “like pearl and ruby where the white teeth shone through the parted lips.” This is not a sinister beauty, as it would be in Dracula—the description is almost verbatim, as Browning remarked in his introduction. It’s interesting to note that in this earlier work Stoker was thinking of the mouth as both an organ of sex and violence. This maiden is not violent, but those white teeth have something animalistic about them, as though a rapacity is just barely contained.

No rapacity is present, or suggested, in “A Baby Passenger” (1899), which presents Stoker’s deeply humanistic side, a side that even in the terror tales asserts itself repeatedly against those Sturm und Drang surfaces. Dracula is, after all, a novel about male friendship as much as anything. In painterly terms, the Stoker of the Gothic-infused tales treats his action scenes with slashing blacks and iron grays, but in the quieter moments—which, I think, counted more for Stoker personally—top layers of bold, resolute color give way to a range of gradations, each a shade lighter than the last until, in the end, we have something vapory, ethereal, delicately human.

Our first impression is that this story will be a rough one, of a jocular nature. A man journeying by train near the Rockies has an annoying, howling child. The men in the car take turns making disparaging remarks, until we learn what has put the father and his child in this situation. The status quo has been altered; what follows is decision time, and Stoker’s characters are always at their most compelling when forced to make decisions. That humor is brought to bear on this gentle and gutting interlude that started loud and descends toward murmurs only bolsters the feeling of loss that moves seamlessly from story to reader to the reader’s own sense of loss in his or her experiences. Baby henpecks father, as wife would. It’s a ghostly invocation of a former family dynamic. It’s also further proof that quiet Stoker is often efficient Stoker, whether in Dracula or this previously uncollected story.

The journalistic pieces in this superb anthology have a knack for coming off like fiction, only without much in the way of narrative. Reading a piece like “Where Hall Caine Dreams Out His Romances” (1908), you wonder, mostly, what the hell it is. Part paean to a writer, part travelogue, the piece plays with form, the language light in places, tamped down further in others, so that the effect is a blend of archness and ardor, like Stoker is improvising a sketch, with the suggested form—the send-up of form—meaning more than the content contained in the form. In present-day terms, a “fiction” rather than a story.

There is illuminating esoterica on display in the final portions of the anthology for Stoker aficionados, like a catalogue of the books he owned. Not surprisingly, given those humanistic flourishes that mark Stoker’s best writing, he was what we’d think of today as a Whitman fanboy. Loads of Whitman on those shelves. The pieces of miscellany pertaining to Stoker’s library have a narrative of their own, with the compiling leading to an eventual 1913 sale that, shall we say, doesn’t come off particularly well, even with those Mark Twain autographs. Blasted expectations, then, both in estate sales and in literary afterlives.

Stoker deserves his reconsideration as an author of myriad valuable, if not quite canonical, works. Or, perhaps, a first proper consideration, with Dracula’s formidable bulk relegated to a crypt that allows some other works to take their turn out in the sunlight, so that we might see them for what they are, and Stoker for the writer we had not thought him to be.