- El muerto al hoyo y el vivo al baile . . .

(The dead to their graves and the living to the dance floor) - Colombian salsa group Fruko y sus Tesos, “A la memoria del muerto”

Maira Alejandra Martínez Suarez is sweeping away another layer of dirt when the bullets come flying overhead. She’s twenty-six years old, and with her French braid tucked under a brand-new baseball cap, she looks more like a rec-league softball pitcher than a forensic anthropologist under fire. She grabs her shovel, paintbrush, and dustpan and, standing in an open grave, peeks over the ledge of moist earth. She scans for incoming fire across the clearing dotted with body-sized rectangular pits. Her Colombian army bodyguards, belly-down, shoot out into the surrounding brush. A ranch corral is too far for escape. She crouches, comes eye to eye with a silver tooth in a half-buried skull and starts to pray, lying in a grave she’s digging.

That was a year ago. Gunfire in the darkened valley below revives the memory of the ambush. By now, taking cover in an open grave seems almost quaint compared to what Martínez and a dozen Colombian forensic anthropology teams have faced in three years of exhumations. They’ve ridden mules into African-palm groves in the north, trucked to cattle ranches through the central valley, hauled canoes into the mosquito-infested jungles of the Pacific coast, and flown out to the untamed wilds near the Venezuelan border.

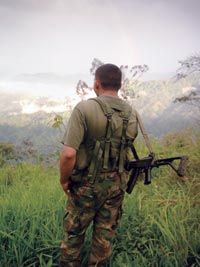

This time, the scene is an abandoned paramilitary camp, a few days’ trek up the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta, at Cerro Mendihuaca, in the territory of Hernán Giraldo-Serna, the former paramilitary boss known as “The Lord of the Sierra.” Word is that despite his publicly televised demobilization and confession, the paramilitaries are back, rechristened as Black Eagles. What guerrillas are left in the upper reaches of the Sierra have also ventured down to wage the latest in half a century of turf wars. The kids of the Córdoba anti-guerrilla brigade, our army escort, have tucked in up the hill, in a jungle redoubt of hammocks, bamboo, and sandbagged guard posts. Lately, say the soldiers, things have gotten “hot.”

There could be anywhere from eight to fifteen bodies to discover on this expedition, and Olger Castro, a federal prosecutor, fails to convince a local farmer to let us use his mule on the march up, not even for money. In general, Castro dreads these trips to the remotest corners of Colombia. His job is to be present when a body is found, to officially designate a crime scene, but he’s past fifty and from the Eastern Plains, where the land is flat and open and people get around on horses. He’d always thought of lawyering as a good desk job, not one that would have him sweating up steep slopes. He’s unhappy about slinging his hammock in a crumbling adobe hut, under a sagging roof, the walls painted camouflage and pocked by bullets. What else is he going to do? He’s got a daughter to feed. Before story time, there’s debate about whether it even makes sense to stay the night. There’d been gunfire earlier, as the day waned, after some of the anthropologists’ security escort had marched off insubordinately to find better shelter, and nerves are frayed. “It’s Colombia,” explains Castro. “Uniforms are easily confused.” After the fire dies down, Castro rattles off a spoken-word ballad, “The Greenhorn Hunter,” from his cowboy home:

After such a long life, brother, and so much work

Death comes to collect, what a cryin’ shame!

I’m tired of fighting, by God, sowing banana and plantain

Tired . . . of being a ranch hand after I’d owned a farm.

What say we take a rest awhile

And make some shade, so the sun don’t burn so bad.

In the morning, the snow peaks of the Sierra shine sunrise-orange across the valley. It’s all uncolonized territory from here; sacred land to the local Kogi and Arhuaco natives. Over breakfast of leftover rice and fresh coffee, the soldiers trade stories of killing and engagement. “It was like the movies,” says one, spitting out some mimed rounds from a mimed gun. Twenty-seven guerrilla bajas or kills for his brigade, year-to-date. They took out a coke lab, just over there, the week before. Our elevation is 2,409 meters, according to the government-issue GPS, and this forensic unit is looking for its 141st body this year. Martínez sips coffee as her assistant takes the DuPont biohazard jumpsuits, latex gloves, and face masks from his oversize pack. Castro asks for a second cup, intuiting a long day.

Before long, we’re gathered in front of three casket-sized depressions in a vine-covered hill, miles from nowhere. Our informant, a nervous little bearded man who kept his face hidden through the lower, inhabited parts of the trail, tells us that there may be four people buried at the site, if this is the place where a pair went into one hole, he says, head to toe.

“Killed this one with a Venezuelan gun,” the informant says, “in his sleep.”

Martínez’s assistant, Julio Eliecer Leiva, a jocular, round gravedigger with a Shakespearean sense of humor and prolific sweat glands, has already set to the plot with his shovel, while the security guys, in the heavy black uniforms of the Colombian FBI, known by its Spanish acronym DAS, take comfortable positions around the perimeter and begin swatting at mosquitoes. It feels more like a lunch break on a long hike than a crime-scene investigation. Leiva starts talking, between swings of the spade, about the last time they’d been in the region, when they’d lagged behind a fit local campesino who led them to the top of a ridge, where there were two holes: one the slight depression indicative of a decayed body, the other deeper and empty.

“What do you think happened there?” Leiva challenges me, resting on his shovel with a mischievous look. “There was only supposed to be one body.”

The cliff, he says by way of a hint, was high and exposed. And then he starts shoveling again, throwing the dirt over his shoulder onto a mounting slag heap. “Assassins were so dumb,” he says, “they threw the first dirt over the cliff, and had to dig a second hole to fill the first.” Leiva mimes the head-scratching look he imagines they had when they realized they’d needed to dig another hole to fill the first. And then he laughs, and returns to his own gravedigging.

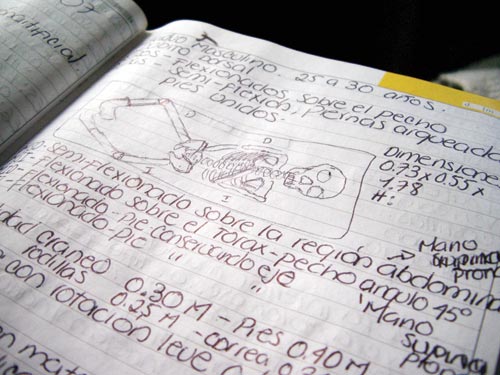

A rumpled blue sheet and a busted agro sack—makeshift caskets—found under some dead leaves indicate that the tombs have been raided, and after more than an hour of methodical digging, Leiva can find no stray remains. When he gives up, grumbling that there’s nothing there, the informant leaps in, Hamlet-like, and stabs at the dirt. “It’s my brother-in-law,” he says by way of explanation, and then a heel appears, and later a bone sticks out of the excavation wall. Martínez logs identified bones in her field book, a colorful academic day-planner with notes on the burials of hundreds of Colombian dead. Castro clicks the ballpoint pen clipped to his army green T-shirt and fills out a case file before this crude jury of peers. “Why did you kill them?” he asks.

“Because they were going to turn in Don Hernán,” the informant says, passing the shovel back to Leiva. He then thinks a moment, and adds, “It was five years ago this Sunday.”

I ask the informant why they took the trouble to go so deep into the jungle, so far up the mountain, to bury the victims. “Because of the dogs,” he says, finally betraying the faraway stare of Colombia’s troubled rural class. “And because el pecado acobarda”—sinning makes a coward.

- Maria Martínez, in the white shirt, with her forensic anthropology team half-way up Cerro Mendihuaca.

Is it possible to make peace and war at the same time? As paradoxical as it seems, this appears to be happening in Colombia. Normally, forensic anthropology is a glorified cleanup operation: at war’s end, finger some bad guys, dig up the dead, use this to understand what happened, then seek ceremonious reconciliation. Argentina in the 1980s; South Africa in the 1990s; Kosovo in the 2000s. In Colombia, though, no former dictator channels national ire. Narcotics trafficking, whose tendrils reach into every layer of Colombian society, spreads blame for brutality thin. Proponents call the current “truth clarification” a “rolling peace process” that with each uncovered crime justifies itself and gains momentum. Opponents call it a farce.

In July of 2003, representatives from the government of President Álvaro Uribe, including his high commissioner for peace, Luis Carlos Restrepo, met with leaders of the largest Colombian paramilitary group on their own turf, in a cattle-farming outpost called Santa Fe de Ralito. This paramilitary, which fought under the banner of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC, had imposed a cease-fire in late 2002. They had long since grown beyond being citizens’ defense brigades organized to combat the guerrillas in the isolated places the government seemed unwilling or incapable of securing. According to Human Rights Watch, it was the threat of extradition to the US for drug trafficking and terrorism that helped push the paramilitaries to the negotiating table.

In Uribe, whose father had been killed by guerrillas, the paramilitaries saw an ally. Despite their fear of extradition, paramilitary leaders came from a position of enormous strength at the turn of the century, having made extraordinary gains in territory, power, and wealth. The “Ralito Accords” declared the end to an “exploratory” phase of a proclaimed peace process, and initiated a phase of so-called negotiation, in which the paramilitary committed to the disarmament of the totality of its troops, while the government would work toward facilitating the full reintegration of former paramilitaries into civil society.

The document, signed by nine of the most feared warlords in Latin America, was immediately condemned as an astonishingly arrogant expression of bad faith. At best, it was met with guarded optimism. It contained no references to criminality, brutality, or victims, and had the government treating the AUC on equal terms. Its tenth and final point “exhorts the international community” to support the effort to strengthen Colombian democracy, and to aid in “deactivating the violent factors which affect it.” Instead, every human rights group, from within or without the country, railed against the Ralito Accords as the charter for a vast and deeply consequential impunity.

For the next two and a half years, the paramilitary, congress, and the Uribe administration engaged in a complicated political dance with very high stakes. While congress debated a new Justice and Peace Law, the government failed to muster the financial and institutional resources necessary to manage the nearly 25,000 demobilizations that flooded urban communities with unemployed and unemployable former paramilitary soldiers with deep psychosocial scars. At the same time, the government was attempting to finesse US pressure to extradite paramilitary bosses, including signatories to the Ralito Accords, for narcotics trafficking, without providing amnesty to nonparamilitary traffickers. Furthermore, if negotiations in congress failed to produce an amnesty law that satisfied the paramilitary, then Colombia would find itself faced with a rearmed and resurgent right wing ready to fight to the death.

But what dogged the process the most, despite the intractability and complexity of other issues—including whether amnesty offered to paramilitaries should also apply to guerrillas, even without a cease-fire from their end—was the question of accountability and justice.

No one in Colombia debated that the paramilitary had been both criminal and brutal, except perhaps the paramilitary bosses themselves, who continued to tout a right to wartime self-defense—at all costs. Perhaps the most visible symbol of this brutality is the massacre at Mapiripán, a riverfront town in Meta province where, over several days in July 1997, more than a hundred paramilitary fighters hacked, tortured, dismembered, and otherwise murdered up to forty-nine people in an effort to drive out the left-wing guerrillas from an important drug-producing region. Today, a countrywide death toll runs anywhere from 8,000 to 31,000 people, depending on who is counting. That there is no agreed-upon tally, or centralized list of the disappeared, is symptomatic of the broader distrust on all sides of the amnesty debate.

In July 2005, Uribe signed law number 975, a document that had been carefully worded to eviscerate its prosecutorial potential in favor of the paramilitary. It gave sentence reductions for time spent in negotiation, resulting in potential jail terms of just twenty-eight months for some of the signatories to the Ralito Accords. It required confessions from paramilitaries, but neglected to require the confessions to be true. It imposed absurdly short statutes of limitations and severely limited victims’ participation in criminal proceedings. It sounded as if it had been written by the paramilitary.

But then, something strange happened. Colombia’s Constitutional Court reviewed the law, and instead of scrapping it, as three dissenting justices ruled, the six-justice majority singled out the glaring flaws and made amendments. Confessions now had to be true. Jail terms were the agreed five to eight years, no less, and should a paramilitary be found to have failed to confess to a crime, the case would be moved to ordinary criminal law. Investigative time restrictions were lifted and proceedings were opened to greater participation by victims. Jóse Miguel Vivanco of Human Rights Watch declared, “The court has finally given the law some teeth.”

Once revised, the law required action from no fewer than twenty-one different bureaucratic and public institutions, from police divisions to courts to special jails and registries to the newly minted National Reconciliation Commission, itself a multi-agency holdover from earlier negotiations. And, mockery or not, the law at least made a show of answering the most complex and practical questions of large-scale peace processes. Who should take care of demobilized child soldiers? How will victims’ families be represented? What kind of reparation, if any, might they receive, and how will these sums be distributed? Should confessed paramilitaries be allowed to distinguish between illegally and legally obtained assets? What exactly constitutes an “illegal armed group” and, in a fading echo of the trials at Nuremberg, how much authority should be attributed to the hierarchies? What’s the difference between a “forced disappearance” and a kidnapping? When are the actions of illegal armed groups seditious? When are they no longer just “illegal armed groups” but, as the US State Department decreed of paramilitaries and guerrillas, “terrorists”?

The trellis on which paramilitary demobilization is being trained is a law called Justice and Peace. Article 1 of the law, when considered in the context of Colombia’s seemingly endemic violence, lays out a bold objective: “to facilitate the peace process and the collective or individual reintegration to civil life of members of illegal armed groups.” Victims can claim a right to “truth, justice and reparations.” Article 15 covers no less than the “Clarification of the Truth,” and requires the demobilized to collaborate in investigations into the whereabouts of the kidnapped and the disappeared. Clandestine gravesites like those in the Sierra are to be turned into crime scenes, to be used as evidence against the sworn confessions of paramilitaries. In other words, the law launched Colombia on a grand mission to reconstruct and confront a gruesome past. The only problem was that the past was yet to be past.

By the fall of 2006, just as the first public confessions were being televised, a series of bruising political scandals began to reveal the extent of suspected ties between the paramilitaries and lawmakers close to the president. According to several Colombia-watchers I spoke to, this was no accident; the paramilitaries were letting the government know that too much pressure meant they wouldn’t go down alone. Under investigation from both the Supreme Court and the attorney general’s office, three congressmen from the president’s side of the aisle were jailed for collaborating with paramilitary groups, and dozens of others went under investigation. One senator detailed meetings he had with paramilitary commanders in 2001, during which a pact was signed to forge an alliance leading to disarmament negotiations. Colombians began to wonder if the ties would reach the president and bring him down at precisely the moment the rickety wheels of justice seemed to have been set in motion. The law was on the books. There was evidence that politicians with ties to paramilitaries had helped shape it. Teams were out investigating crimes—and being shot at. Martínez was hiding in graves she was digging. And by the time I arrived in Colombia to observe her work, the peace process had taken several more turns to the grotesque.

Hernán Giraldo-Serna, Lord of the very Sierra that Martínez was busy investigating, claimed in his televised confession that he knew nothing of mass graves of victims, but that he “can ask around.” Giraldo-Serna had a thousand people, including allegedly paid Kogi and Arhuaco natives, trucked in to hold banners and chant support from the street below his confessional chamber. At the time, six months into the process, only forty of 2,812 identified paramilitaries had appeared to give confessions—700 remained at large. Later that month, another paramilitary boss—known, because of his light skin and blond ponytail, as “The German”—topped Giraldo-Serna by bringing a country music band and confetti for 300 “supporters” who cheered his prison motorcade and responded to his hip-shaking from a sixth-floor window. Their noise drowned out the voices of stunned assembled victims across the street. President Uribe, meanwhile, has yet to pronounce the word victim in association with the paramilitary, and to date the Colombian press continues to reveal allegations of “parapolitical” scandal.

Still, around these outrageous displays of bad faith swirls what Colombian activists like to refer to as “civil society,” in the shape of victims’ rights groups, opposition parties, nongovernmental organizations, a resourceful press, and the checks and balances of Latin America’s longest-running democracy. “What started in Ralito as a political agreement bent on impunity has taken an unexpected turn towards accountability,” the International Center for Transitional Justice’s Eduardo Gonzalez told me in New York. “Colombia has more moral and institutional reserves than initially suspected: civil society, independent rule-of-law institutions, and the press have all done their part to impose strong parameters to what was the original impunity script.”

I went to speak with a lot of the people in Colombia who have been involved in the struggle to bring down the paramilitaries and hold them accountable for their actions, and there is one thing the activists all had in common: bulletproof doors and bomb-resistant offices. While Camilo González Pozo of the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ) champions reparations (“Just 1.3 percent of the budget set aside for war victims, compared to the 4.6 percent we allocate for the military”), Jorge Rojas of the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES) calls it water under the bridge. “I prefer to talk to high-school students over politicians,” Rojas told me, pointing to a map with 116 places in Colombia where his organization had determined the war was still “on.” “We should be thinking about the idea of a lost generation.” So should we be digging that generation up?

Back in Bogotá, I go to the bunker of the fiscalía—the public prosecutor—to meet with the head of the Justice and Peace Unit. Luis Gonzá-lez León is a practical-minded man with an office full of Catholic iconography, and a polished discourse about “getting things done.” As a Paisa or native, of the same western region around Medellín that Uribe is from, León sees taking action as in his nature. “When we go back, not even the victims recognize the locations,” he says of gravesites. “Postponing the search just doesn’t make sense.” He takes me upstairs to a room with four chained-down laptops and two men in suits, who have been developing the online database of exhumations, which he is encouraging Colombians to visit. “Disappeared?” reads the widget. “Click here.” The search filters by location, age, and clothing type (choose from a drop-down list including “teni” shoes, tie, and military uniform), and promises to return photographs of evidence, though I’ve never managed to see a picture myself. Follow the current tally in a sidebar: for September 1, 2008, 1,300 graves found, 1,568 bodies, 488 with preliminary identification. Below that, the number of fully identified victims lags. Only 217 have been returned to family. Twenty-one more are pending.

León’s office sits behind five security checks, on the fourth floor of the nerve center of Colombian law enforcement, which happens to be adjacent to the US Embassy. Samples of a national poster-campaign that is coordinated with television and radio ads hang on the walls. HAVE YOU BEEN A VICTIM OF ILLEGAL SELF-DEFENSE GROUPS? CALL 018000916999 DURING OFFICE HOURS. The spines of filing books in a reception cabinet read VICTIMAS NO. 1 2 3, AÑO 2005. An officer in a suit, with a badge hung from a lanyard, flips through one of these files, page after page of chart printouts and penned-in forms. “I’m looking for one name,” he says, venting his frustration on whoever is closest. A lawyer comes in to ask for some guidance. He has a client from the FARC guerrillas who wants to demobilize, but his case has been slow to go through—what can be done? Then the US Embassy liaison for the Justice and Peace Unit pushes through the glass doors and disappears into León’s office with some advisers.

Meanwhile, the Colombian attorney general has publicly declared his offices “overwhelmed” by the magnitude of the investigative tasks requested of it by law 975. He needs more prosecutors, he says, at least seventy more than the twenty-three he has for nearly 3,000 cases. He needs more than the one DNA lab in Bogotá, where bodies are literally piling up. He needs better guarantees for the security of his operations, and for the victims. He’s snatching up all the young forensic anthropologists the National University can produce. The hotline alone has brought in over 4,000 tips to date—each needs to be individually investigated, then scheduled for crime-scene forensics with one of the official teams. Ironically, public confessions announce the locations of future investigative operations, and increase the likelihood of finding sacked graves.

This is what appears to have happened to us in the Sierra, where our presence was clearly well known. And once a body is buried twice, Martínez explained to me, “it’s gone forever.”

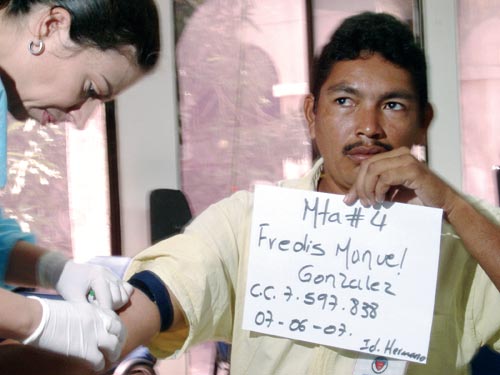

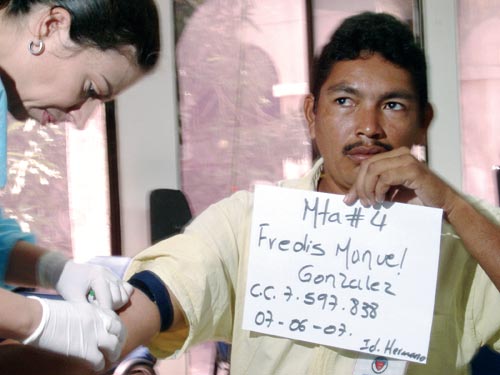

And yet. I think of Netalina Ariza, sixty-eight-years old, arriving to the Santa Marta DAS headquarters to have a blood sample taken. She’s here with her husband, who sits in the desk chairs with a look of subdued confusion and mistrust. They have come to identify their daughter. Ariza is leathery and feisty—toothless but dignified in her thin summer dress—and as resigned to hardship as they come. Of fourteen children, nine are still alive. One died at age four. Two died of disease. Two were assassinated. On October 22, 2003, at around eight in the morning, six men arrived at her farm, La Cita, in rural Pibihay, demanding that her two youngest, a boy and a girl in their early twenties, come with them. She has a vague remembrance of what the men were calling each other—“Nedo,” “Alias Ariza,” “Richard,” “Alfredo”—and of why they had come around. They said they were angry about talk around the killing of a union organizer.

“We had a clean family,” Ariza says—simple folk, dedicated to the land. The girl was killed right there, just outside the house, three bullets. The boy, they think, a little farther down the road. “What else were we going to do,” Ariza says, “but go inside and cry?” When later they went into town, they found no one willing to approach them. Then threats came in the form of messengers telling them to keep quiet. So for more than two years they just kept quiet.

A prosecutor in the DAS office had swabbed Ariza’s arm and taken a few vials of blood. She’d photographed the woman, had her sign with an illiterate X a DNA release form, and lifted fingerprints. The prosecutor promises the remains will be returned for proper burial within six months, and she apologizes to the Arizas for the delay. It’ll be good to put her away in an osario, won’t it? “We’re still looking for the boy,” Ariza answers. “We’d love to find him.”

- Forensic specialist examines remains at the Santa Marta morgue. Marks like silver teeth can mean quicker identification.

It’s hard to think of this exchange as what opponents to the peace process call “a joke on the victims,” “a macabre game,” or “digging up for the sake of digging.” Where the broad projects of politics meet the distant lives of rural Colombians, something small and significant may be going on.

On April 24, 2007, a year after the revised law 975 went into effect, Colombia’s main daily, El Tiempo, published a remarkable six-page special report, on a Tuesday before Easter, when millions of Colombians were preparing for a popular vacation, headlined “10,000 bodies sought, 535 found last year.” The report was gruesome. The paramilitaries ran regional training camps to teach their ranks how best to quarter bodies—“like chickens”—to fit into smaller holes. Machetes were preferable to chain saws for this task, explained one demobilized and jailed paramilitary fighter, because clothes would get caught in the teeth. Quartering was a practical solution to the problem of disposal—easier to fit a folded body into a small, deep hole than to dig a body-sized grave, the logic went—and was reportedly practiced, and demonstrated, on live subjects. Investigative units like Martínez’s had found bodies everywhere, in every state imaginable: burnt, thrown into rivers, buried, fallen from cliffs. The cumulative effect was undeniable. “Anthropologist returns from Kosovo to dig up the paramilitary dead,” ran one headline. “Armed with a machete and shovels, lone woman digs in search of her daughter,” ran another.

The editor, Luz María Sierra, inspired by a story of fratricide she had heard from the butler of her large cattle farm in the Eastern Plains, laced the report with voices of the victims. Colombians knew that the paramilitary had brutalized them, Sierra told me in one of Bogotá’s chic outdoor espresso bars, but they can be inured to their own endemic violence. Even if her paper didn’t have the resources to “do 10,000 cases of CSI,” a few well-chosen stories might, she hoped, touch her readers.

“They made my brother carry my dead wife,” says one headline. “Nine years I’ve waited for them to tell me where Jaime is,” says another. “I dream of finding him under some branches.”

A flood of letters came in that day and the next, and then Colombians left for the beach. “Few discoveries have shaken us thus, and few are as difficult to tell in words,” wrote Sierra, “but perhaps most troubling is the sensation that the magnitude of the task [of revisiting these crimes] has overwhelmed the country.” The special report concludes with the disappeared in Guatemala, Peru, and the Balkans, where exhumations were undertaken, as they were not in Colombia, once armed conflict had subsided. Finally, an influential Colombian anthropologist, and expert on the period in Colombian history fifty years ago known as La Violencia, provides the last headline in the series. “Digging up the dead,” it reads, “is not enough to heal the country.”

- A lab specialist draws blood from the brother of a victim to analyze the DNA and, possibly, close one more case.

Julio Eliecer Leiva, Martínez’s assistant, had a favorite joke, which he tells sweating and half-submerged in an open grave, in between swings of the spade. Saint Peter and God are talking in heaven, it goes. “Let’s make a country,” God says, “with perfect weather, beauty beyond imagining, mountains, streams, fertility, beaches, the works, and call it Colombia.” And they do. And Saint Peter looks down on it in wonder, and says, “You think we went a little overboard?” And God answers: “Wait till you see the sons of bitches we’re going to populate it with.”

That’s the way it is in Colombia. Jokes in a grave. War and peace at the same time. “For every hole that’s dug to take a body out,” complains the Colombian army lieutenant responsible for protecting Martínez’s team on the dig, “somewhere else another hole is opened to drop a body in.” Digging up bodies is not a means to close a chapter on Colombian culture; it is the culture.

On May 13, 2008, the US Department of Justice announced that fourteen of Colombia’s paramilitary bosses, including Hernán Giraldo-Serna, had been extradited to the United States to face drug charges. The vice minister of justice promised to bring closed-circuit television to American chambers to allow Colombian victims to hear further testimony from their accused. Uribe promised to make all goods seized by US authorities available to victims as reparations. Victims who had been attending the open confessions of the paramilitary bosses now wondered how they were supposed to get a visa to the US, let alone pay for a ticket. News reports indicated that by August at least fourteen attempts by the Colombian attorney general to reach the extradited had failed. All Justice and Peace cases against the men remained open, but without access to the accused, Colombians began to wonder what had become of reconciliation and reparation.

In the month before the mass extradition, which Uribe had engineered, a prominent senator, Armando Benedetti, declared law 975 a “failure.” Of registered victims, his PowerPoint slide presentation in chambers showed, only 9 percent had legal counsel, and nearly a hundred had received death threats. At current staffing, crime-scene investigators would need to tackle 3,001 cases per person, and each prosecutor was facing 5,752 cases. Twelve psychologists would need to treat 10,447 people each to address the 125,368 registered victims. Of 31,671 demobilized paramilitaries, only 3,257 are facing Justice and Peace charges; another 19,000 had simply skipped the whole deal. And of these 3,257, only four had completed their testimony. At that rate, Benedetti impishly noted, Justice and Peace would be complete in 2,157 years. Worse, though former paramilitaries had confessed to 4,297 homicides (as if it were a badge of military prowess), they’d owned up to only forty-five cases of forced displacement. The victims, on the other hand, leveled 9,476 accusations of forced displacement, probably just a fraction of the real toll in internally displaced. And at the current rate of successful seizure and forfeiture, including 4,518 cows and one used, poorly working, 29-inch TV, victims could expect checks, should payment ever be made, equivalent to $3.75.

Leiva tells another story about a dig that required walking in to the site under cover of darkness for security reasons, then working all day, with no luck. A ten-year-old arrives on the scene, and to protect his innocence, the security people shoo him off. But then Martínez calls him over. The child asks what they’re doing. As gently as she can, Martínez says that they’re digging for people who are dead. “What?” the child says with a titter. “You want the dead people?” The river grew months ago, he says. “We were finding bones miles downriver.” So the team packs up and trudges home.

At the end of six days in the Sierra, walking out with bones in black plastic bags that dangle from the ends of shovels, Leiva, Castro, and the security guys have had enough of dead bodies. We take a long bath in the crystalline flow of the Guachaca River, scrubbing out our clothes on the rocks and watching tourist buses drop off inner-tubers. That night, back in bustling Santa Marta, a beach town with vallenato music spilling out of noisy beer halls, Martínez goes to her parents’ house. The rest of us land at the Tropical Club, a packed, mirror-clad brothel down a thin colonial street. The DAS agents have left their uniforms and badges back at the hotel. Pole dancers gyrate to thumping beats, and a young girl tells me she’s planning on enrolling in flight school. She wants to know why Olger Castro looks so glum.

Ten thousand bodies sought. True, this is a peace process that began in the mud of a cattle ranch and has never gotten much further off the ground. It has been mired in contentiousness, bad faith, double crosses, and reverses. But like the bodies of the Colombian dead, it just won’t go away. “It’s very complicated to make a body disappear,” Maira Martínez explained to me in the Sierra Nevada, sitting on her folding campstool, waiting for Leiva’s spade to ring out against some bone. “Eating it is best,” she said, “but not talking about it is even better.”