It was several days after the deaths in Bagua, and we were in a tiny car flying down a washboard gravel road—some left-of-nowhere oil company throughway punched into the Peruvian Amazon—when the paramilitary cops flagged us down. Everybody in the back was asleep: Plinio leaning on Alcides, Alcides—snoring—leaning on me. I elbowed Plinio. There are three rules for reporting in the Amazon: 1) add two screwups to every plan; 2) there is no such thing as a “little problem”; and 3) you never—ever—go in without an Indian guide. Plinio was mine. He was wiping sleep from his eyes as the cop, in military pants tucked into black boots, approached the car, a machine gun over his soldier. I wanted to go home. “It is routine,” Plinio said. “It is the state of emergency. He’s checking our IDs. Just remember our story.” He meant to remember the lie we’d concocted: that my partner, Duncan, and I were making a documentary about the Amazon’s threatened biodiversity. In fact, we were there investigating the impact of Peru’s booming oil industry on the forest’s indigenous villages.

Many people don’t realize that Peru controls most of the Amazon’s headwaters—a massive chunk of the rainforest second only to Brazil’s portion—or that Peru’s past two pro-business presidents have bet the ranch on the area’s oil-rich energy lodes. Since 2007, the country’s oil-concessions agency, Perupetro, has signed dozens of contracts with international oil companies, granting claims that blanket the region. EarthRights International, a US-based environmental group, says that over half of Peru’s biologically diverse Amazon region has been added to oil maps in the last four years. Some—if not all—claims overlap five government-protected parks established as refuges for rainforest peoples living with little knowledge of or care for the modern world. That means big problems for natives with vulnerable immune systems who have increasingly greater odds of running up against outsiders and their germs. Historically, oil companies operating in the Amazon have run roughshod over indigenous populations while counting on the remoteness of the rainforest and the silence of the people to conceal corporate mistakes and neglect. Natives, however, are starting to push back with the help of lawyers, rights experts, and technologists out to create new rules of doing business. The friction between jungle dwellers, oil companies, and development-hungry governments in recent years has led to strikes, mini-revolts, and heightening tensions.

Those tensions came to a deadly head in the early morning hours of June 5, 2009, on a remote oil road in Peru’s northern Amazon, near a town called Bagua. To show their anger with land reforms, the people had made a human roadblock to cut off traffic and halt oil operations. After two weeks of lost revenues for the state oil company, a unit of Peruvian paramilitary police with machine guns and riot gear tried to dislodge the three thousand spear-carrying protestors. What happened next is a matter of dispute. Police say some natives who had obtained guns started shooting at a helicopter. Natives say paramilitary police with AK-47s attacked without provocation. As Bagua made world headlines, allegations surfaced of beatings and torture, of burned bodies and limbs hacked off with machetes. Newspaper accounts said that Bagua protestors took thirteen police officers hostage, eventually executing them. All told, some two hundred people were hospitalized and thirty-four were killed (both police and protestors).

President Alan Garcia dubbed the natives “terrorists” and blamed Bagua on Alberto Pizango, the president of a prominent native coalition called AIDESEP. Pizango for months had been negotiating on behalf of the country’s natives, calling them off and back on at will. In the days leading up to the Bagua confrontation, he was in what seemed to be almost daily meetings with Peru’s prime minister. At one point, after Pizango called on his followers to take to the streets in force, the government indicted Pizango for treason and sedition but did not arrest him. President Garcia suggested that natives were having their strings pulled and pocketbooks lined by his populist political rival Ollanta Humala and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, who Garcia hinted was fueling an “international conspiracy” to disrupt Peru’s oil and gas production in order to keep the country in the position of having to import oil from Venezuela.

In fact, Chávez, a strident, oil-rich, anti-US nationalist, has publicly embraced Humala, who lost a runoff election against Garcia in 2006 (and is set to run again this year); and days before my arrival, Peruvian Congressman Edgar Nuñez announced that his national defense committee had proof that Chávez was funding protestors. Humala’s political party claims as its power base a network of local officials in remote provinces; were regional government mayors and administrators using tax dollars to pay thousands of citizens to engage in what many people see as domestic terrorism? Another indigenous leader in Peru, Vladimiro Tapayuri Mirani, the president of the Amazon Indigenous Committee, came out supporting Pizango and calling for an autonomous state for natives trying to defend their forests. In a translated interview with the US radio program Democracy Now! Mirani said, “Alan Garcia has violated the rights of the Amazon peoples, implementing anti-Amazon laws without consulting us. Now, indigenous leaders like Alberto Pizango are being persecuted. The struggle does not end when the law is overturned, but when the Amazon is free. We want regional autonomy, an Amazon state. The people have finally realized that capitalism has been hurting our development for many years.”

More and more, the strikes, Bagua, the anger and frustration I had seen in a half dozen journalistic trips into the Amazon all seemed to portend a budding revolution. Garcia was adamant, telling reporters at one point that natives had the wrong idea. “These people are not first-class citizens,” he said. “Forty thousand natives think they can tell twenty-eight million Peruvians they don’t have the right to come around here? There is no way. That’s a serious mistake. And whoever thinks that way will lead us into irrationality and a backward primitive state. The entire country is asking for order, energy, and action from the government, within reasonable limits, and the authority of the law. That’s what the government is going to do. And any unfortunate incident is entirely the responsibility of these pseudo-leaders, pseudo-natives who are instigating the most poor of people to take illegal and violent action.” The prime instigator, in Garcia’s version of things, was Pizango, who had, hands down, become the most powerful Indian in Peru.

I met Pizango at his office days before Bagua and before he became Peru’s most wanted man. AIDESEP’s headquarters are in an industrial part of Lima; I had taken a taxi and on the way over skimmed several of the day’s newspaper articles about the strike, about Pizango’s on-going meetings with Peru’s Prime Minister Yehude Simon, about the bridges, roads, and oil facilities that had come under native control. I got there and rang the buzzer. Inside, a plump secretary in a skintight shirt sat in a chair behind a glass window. She had long black hair. “Is the Apu”—the traditional name for chief—“expecting you?” Apparently, the press secretary had said nothing about my arrival. I was told to sit and wait. The place was abuzz. Indian men, some in jeans, others in casual business clothes, came up and down the stairs that, as far as I could tell, led to Pizango’s office.

AIDESEP, a Spanish acronym meaning Inter-Ethnic Development Association of the Peruvian Amazon, operates like a labor union, stitching together one coalition from dozens of smaller Indian organizations scattered throughout the Peruvian rainforest. Pizango has made his name in recent years by using AIDESEP’s substantial political clout to pressure the government over its oil concessions on lands titled to natives and by supporting a group of Achuar natives who used bows and arrows to overrun one of Perupetrol’s oil pipelines in northern Peru.

To kill time while I waited, I browsed through calendars with pictures of natives in ceremonial dress, announcements of rights symposiums, and posters with cartoon renderings of children practicing good sanitation habits. I ran my finger across the native headdresses and bows and arrows that hung as displays on the wall. In a glass cabinet, someone had hung several pages from recent newspaper stories, all dealing with strikes and Pizango. A few showed him with Prime Minister Simon after one of their many meetings; Pizango wore a red-and-black feathered crown.

I waited for two hours, returned the next day, and waited for another hour before I was asked into Pizango’s sparsely furnished office. I was told by an aide that the next day he would go to the Ministry of Justice to make a formal declaration against the sedition charges, so I proposed to the Apu that Duncan and I do an on-camera interview in the taxi with him, and he accepted. Before leaving I asked about Congressman Nuñez’s claims about Hugo Chávez. He scoffed. “That is propaganda,” he said. “The native communities are paying.”

The next day, we loaded into the car with cameras rolling. Pizango told us that the charges of treason had made him stronger, that it was a new dawn for natives, that Garcia and Peru alike should get used to the strikes because they would continue, he would continue, until the noxious laws were repealed. The natives had had enough of injustice, enough talk of oil and gas, enough contamination, enough broken promises, enough of the government being absent then high-handed, enough oil money flowing out from under their feet. Later that day, I called Nuñez, who said he had proof that showed Venezuelan funds flowing to the protesters through grassroots support centers named after Mr. Chávez’s alternative trading bloc, the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (ALBA). He told me that the government was going to close those lines of financing. He told me that his office would contact me when details could be released. Then he hung up, and I never heard from him again.

We sped to the airport for our flight to Cuzco, followed by a hair-raising drive up a switchbacked mountain track through the high jungles of the Urubamba region to a gritty little town called Quillabamba. I had read about another tiny Indian village nearby in southeastern Peruvian Amazon called Andioshiari that had joined the national protests. There the preindustrial village dwellers had dug down to a natural gas pipeline owned by an international consortium that includes Hunt Oil, a Texas-based company with a controversial environmental record and strong ties to the Bush family. To show they were serious, the villagers had used machetes to whack apart a fiber-optic cable they found while digging down to the pipeline. Our guide was going to be a man named Plenio Kategari, the treasurer of one of AIDESEP’s member groups, who we were told by Pizango’s people would take us to tiny Andioshiari if we could get there quickly.

In Quillabamba, moto-taxis buzzed the streets. Sidewalk salesmen carried cigarettes, chocolate, pens; gum in wooden boxes hung from their necks. For natives, Quillabamba is the go-to place: a doctor, a judge, a policeman, pots and pans, a baby pig. Getting here can be an exhausting canoe trip, a costly ride in a sun-blistering cargo boat, or an expensive and death-defying bus journey along a road cut into an Amazonian mountainside. The town market is a large gymnasium-size place full of deep, earthy smells—corn, fresh bananas, freshly slaughtered cows. Men with wheelbarrows wait with a few cents in hand to buy a skinned skull, complete with eyeballs. Women with kitchen knives carve the last remnants of meat from the bone. In the stalls, anything you need: insect repellent, knockoff MP3 players, flashlights, mosquito nets, towels. Kids in school uniforms bolt in and out of ice-cream stores and internet cafés.

On a dirt road at the far end of town, away from the bustling market, the headquarters of COMARU (the Annual Congress of Indigenous Peoples of the Upper and Lower Urubamba) resides in a nondescript building with a metal door. It sits across the road from an elementary school for native kids. Plinio met us at the door. He was surprisingly young with cropped black hair, a plaid shirt, and jeans that looked like he had ironed them. The building hadn’t changed since I first visited in 2004, and again in 2005. There were rooms with rows of bunk beds for visiting natives, two offices, and a community meeting room. Sitting me down, Plinio explained in a hushed voice that he had to go check on the situation in Andioshiari, a village he had never been to and knew nothing about except that, like him, they were Machiguenga.

The village had come into increasing contact with outsiders upon the recent arrival of road crews building what is planned to be a highway leading from rural communities in the Peruvian Amazon to the capital city of Lima. “The military was flown in but we don’t know what happened because they are not responding to the radio. I have to go see if people are hurt.” He said the plan was to take the new road into the jungle as far as we could go. “The community is somewhere near the end.” He said he was worried that the dislodgment of the villagers by the troops could have turned violent, but we wouldn’t know anything for sure until we got there. We were to meet a scouting party that would be at the end of the road at 6:00 P.M. the next afternoon. “We have to get there by that time or they will go back to the village.”

I had worked with COMARU twice on journalistic expeditions and, as one would reasonably expect from a thinly budgeted native group, they asked for money for supplies and transport. Plinio did not ask for money for either. I considered this the next day, as Duncan, Plinio, and I piled into a jacked-up Chinese-made minivan with balding tires and found our driver wearing a vest bearing the official seal of the local government of Convención, which forms part of the state of Cuzco. The mayor of Convención is an Humala loyalist. I thought about President Garcia’s suspicions and remembered a conversation I’d had with a white hotel owner in Quillabamba before we left. “The natives are peaceful,” he assured me. “They do not do this kind of thing. People are manipulating them and it is clear that it is Humala and Chávez.” I asked the man if he worked for the government. “I worked for them,” he said, emphasizing the past tense.

Somewhere on the way to Andioshiari, the road stopped being a road, dissolving into a mud track that had been ripped, tree trunk by tree trunk, into the side of a high-mountain jungle. Some fourteen hours after pulling out of Quillabamba, far past our 6:00 P.M. rendezvous, we were spinning and sliding our way through shin-deep mud ruts on a tiny, hairpin road the width of a single bulldozer, with deadly drop-offs on either side. We all sat straight in our seats, jumping out at times to push, as we kept pressing nearer the final mile marker.

All the while, Plinio talked and talked. He told us that it was his job to take news of the protests to remote native communities that had no access to newspapers and television, to get them on board. Plinio, like the COMARU treasurer before him, a man back in Quillabamba named Alcides whom I had come to know quite well, was a traveling blend of politician, grassroots activist, and labor organizer. “These laws that Garcia is promoting are just another way to try to take our traditional lands,” Plinio insisted, as we sped over spine-jamming bumps and ruts. “We will not stop until they are repealed. This is what I tell the communities when I visit them. If we are together we have a chance. If we, the communities, are divided, then we will lose.”

Plinio had been on the job only a few weeks but, with the historic protests in high gear, he had been on a constant, punishing string of trips on buses, motorcycles, canoes, and boats. He said that, like many remote natives, the people of Andioshiari (a place he had never even heard of until the pipeline incident) were hearing talk from outsiders about money and jobs but also whispers about all kinds of breakdowns. Spills. Leaks. Erosion along the pipeline. Water contamination. Noise pollution. Alcoholism. Plinio said his own wife had died a year earlier from a mysterious illness. It was clear: he was readying himself, and possibly being groomed by COMARU leaders, for a political career. Going to Andioshiari was part of the path. He had been in several newspaper articles, he told me, and he promised to give me a copy of a radio show on which he had been invited to speak about the national strikes.

We rode on and on, for what seemed like forever.

Near midnight, we ground to the end of the road. We got out of the car and walked a few yards to look down into a gully. To our utter surprise, we saw glaring lights illuminating a makeshift encampment for road workers, a stage of white light pushing shadows up a mountainside of loose gravel, across the clapboard structures. It was unlike anything I had ever seen, almost eerie. We were late-late, and the Indians were nowhere to be found. Some construction workers walked up the steep embankment to see what was going on. Plinio kicked a rock and shook his head, defeated, with nobody around to help. Then he said, “Look!”

In the distance we saw three tiny points of light bobbing their way toward us—three Indians with headlamps, wearing the traditional cushma robe and carrying bows and arrows. They greeted Plinio. One pointed at the dark mountain and said something in Machiguenga. Plinio turned to me and said that only he could go up to the village tonight. We would have to find a place to sleep. “Tomorrow they will send someone for you,” he said. My heart sank as they disappeared into the trees. I turned to one of the road crew. “Where is Andioshiari?” I asked him. “Somewhere up there,” he said, nodding up toward the dark, forested mountain.

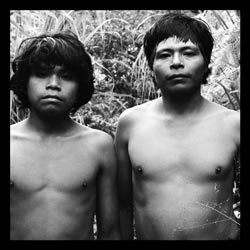

It was cold in the morning, but the men, some shirtless, prepared for the day’s labor by washing their hair in freezing water. The mountain was dense with jungle canopy and tall. One man carried a chainsaw the size of a small car. But our guides up to Andioshiari were nowhere to be found. “They came for you this morning,” the camp boss told us. “There were two of them. Natives.” I was fuming. We got our things and hiked up to the road, and there they were—one with a baseball cap that was too big. He had on sandals made of tire rubber. The other one had longer hair and no shoes.

They climbed like squirrels and understood little Spanish.

“Are we far?” I asked.

“Yes. Far.”

“Are we close?”

“Yes. Close.”

I was drenched with sweat and about to heave when one of the men stopped, pointed through a clearing to what looked like a few shacks with tin roofs. “There,” one of them said proudly. A half hour later, we walked out of the jungle and into the village. There were shacks and cooking fires and kids playing in the dirt beside mangy dogs and the sun pounding.

Though the village had no electricity, one man standing in the door of his tiny wood hut saw our camera and seemed to recognize us. He grabbed his bow and arrow, jumped off the porch, and snapped at his young wife to stand beside him. He stared into the lens, saying something in Machiguenga, then pulled back his bow, pointing an arrow at the sky, and repeated the motion several times. He was doing his best to give us what he thought we’d come for. While we had been stranded all night in the workers’ camp below, Plinio, it appeared, had been winning friends and influencing people.

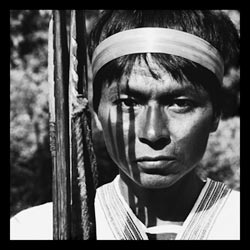

We walked away from the shacks, down a path into a clearing with a view of the surrounding mountains, and onto a hand-chopped soccer field where all the village men stood in robes and face paint and arrows. They were in a line. Some wore baseball caps. One young man held up a sign for President Garcia: ALAN, THESE SPEARS ARE FOR YOU. Plinio was standing in front of them in his cushma, holding a pad of paper and clearly in charge of the photo op. Evidently, no one had been injured over the pipeline incident, and Plinio had been busy setting up a mini-protest for our cameras. Over the next sweltering hour, we filmed the Indians giving speeches, the entire affair emceed by Plinio. Led by him, they chanted “Long Live Native Amazonians.” They held their arrows in the air, shouting in unison. Behind them, across the valley and up the other mountain, the jungle stretched on forever. At one point, one of them fainted from heat exhaustion, and we pulled him under a tree. There were countless pledges to do what had to be done to face off with an overreaching government that was trying to sell the forests out from under them.

When the demonstration was finished, we asked if they could take us to the place where they had dug up the pipeline and been run off by commandos—who, we had been told, were still at the scene with their riot gear and machine guns, waiting to fend off any other of the villagers’ offensives. “We will have to go and ask them for permission for you to come up,” one of them said, hesitatingly. As we waited they fed us bowls of rice and chicken. One of the villagers lent me his spoon and sat watching me eat until I was finished, then asked for it back. After a while, the elders walked out of the jungle and told us that the soldiers had agreed that we could walk up the path, but only with five people and only to film the pipeline from a distance.

Within minutes we were back on a jungle trail, going higher up the mountain, winding our way through thick forest up to a grassy opening where the path opened out from under the trees. The man who had talked to the soldiers was leading the line, and he seemed nervous. He waved at someone at the end of the line for them to go back. “They said only five!” Suddenly, as though from out of nowhere, Plinio, drenched in sweat, made his way past me to the head of the line. He walked quickly through the clearing, motioning all of us to follow him. Up further, as we ascended, I saw a man, the unit’s sergeant.

There was no smiling as we approached. Five or six soldiers wearing jungle fatigues and carrying machine guns stood around; some had riot shields; one wore a riot helmet. The sergeant was a muscular white man who told us not to go any farther but that we could film. With our camera going, Plinio stood before the sergeant, complaining about natives getting run over by companies and the government. The sergeant said he agreed but had a job to do. They shook hands. His soldiers were stern, but as the sergeant loosened up, they did too. One or two smiled. Then they started making their own cell-phone videos. By the end, a mild camaraderie seemed to have been established.

Later, Plinio came up to me flushed with adrenaline, motioning toward the villagers. “They recognized me from the papers!” he said. “They say when they negotiate with the oil companies they are going to call me!” He envisioned a new peace emerging—with him as its hero. Little did any of us know that, far away in Peru’s northern Amazon, things were heating up at Bagua. After we climbed back down to the village, two porters were sent to pack our things down the mountain. After paying them, we sat together in the shade near the construction encampment. I took out my bag of trail mix to share, taking a handful myself and handing it to one of the Indians to pass around. He folded the bag without saying a word, nodded to us, and walked away.

Bagua was carnage. We found out about it after returning to Quillabamba from Andioshiari. The news was full of tales of brutality; images of crying mothers and children; burned, charred bodies; angry crowds; government statements. President Garcia came out insisting that the government had done nothing wrong. All over the Peruvian Amazon, native communities were telling reporters that they were going to increase their protests. Pizango had gone underground to avoid an arrest warrant issued for him as the alleged instigator of the whole thing. Some reports said that people from Humala’s party had whisked the fugitive leader into Bolivia, but that Evo Morales, the country’s first indigenous president, had denied him entry. Within days, the Nicaraguan embassy confirmed that Pizango was being granted political asylum by its Lima embassy, a gesture of support from Nicaragua’s Communist President redux Daniel Ortega to left-leaning political forces in the region that, to varying extents, are being shaped by Chávez’s Bolivarian politics.

We were having something to eat in the hotel restaurant when Plinio came in and sat next to us, leaning over, speaking in a low voice. “I have called a meeting of the leaders of all the Machiguenga communities in the lower Urubamba,” he said, at one point glancing over his shoulder. “We are going to meet and plan solidarity action for our brothers killed in Bagua.” He said the action might take place in the upper Urubamba region in the form of a highway blockage that would stop tourist traffic from reaching Machu Picchu. Another option was to overrun a natural-gas facility in the dense forest of the lower Urubamba. His cell phone rang. He looked at the number and got up from the table, cupping it in his hand and stepping outside. When he returned, he told us to be ready at 3:00 A.M.

Hours later we were loaded into a small green station wagon and heading back into the lower Urubamba, in the general direction of Andioshiari, but this time to a tiny village called Monte Caramelo, near the Urubamba River. And it was clear: we were complicit in something. We were journalists, yes, but we had prior knowledge of an unlawful meeting (thanks to a government-imposed state of emergency that prohibited public gatherings), and we knew that the natives were convening to plan what was essentially an act of domestic terrorism.

On our way out of town, we went by COMARU, where a government pickup truck with an official seal of the local government was parked at the door. It was still dark. The truck had its lights on. Several Indian men stood around it, joking. Plinio got out to talk to them, and after a while, we went on. We drove for what seemed like forever; paramilitary cops stopped us along the way to check our IDs. We stopped for bathroom breaks and snacks in an oil town called Kitini, where a massive engineering company called Techint, which is responsible for building a nearby pipeline, is headquartered. It was like a garrison. There were police with machine guns everywhere. They were training a troop of young soldiers in the street. I managed to sneak a couple of pictures but was seen. A policeman approached and asked if I was a reporter. “No,” I said and apologized.

We hit the road again, speeding. Plinio, who was wedged against the driver’s side door, kept asking the time. “I can’t be late,” he said. “I am the speaker.” After hours of dusty driving on a gravel road, we came upon a few vehicles parked along the roadside. There were the government truck and a couple of the men who had been at COMARU that morning. We walked down a footpath, across a log that had been felled across a stream, and into a clearing where a low-slung concrete building was full of native peasants. Someone was calling roll. The entire list was composed of just three or four surnames, including Kategari, Plinio’s extended family. Plinio got up and introduced himself as the treasurer of COMARU.

As in Andioshiari, there were speeches made by men and women, some of whom spoke little or no Spanish. One man named Carlos Collado said angrily, “We are not the assassins the government makes us out to be. But we will not let our brothers die. This meeting is illegal. But we are here. This shows that we are ready.” One by one, each speaker expressed vehement discontent with the Peruvian government. One woman stood up and angrily told the crowd that it was time for the natives to show force. “We cannot let them die alone,” she said. Plinio delivered a fiery speech. There was bickering but, after what seemed like forever, it was agreed that everyone would return home, spread the news, and in the meantime decide which route to take: blocking the Machu Picchu highway or taking over a natural-gas facility somewhere in the lower Urubamba. The action would be determined after the representatives returned to their respective communities and talked it over.

The meeting broke, and the attendees lined up to sign a document, the illiterate ones signing with a fingerprint. Little had been decided, but for Plinio, it was a political success, another notch in his belt, even more recognition. His speech was strong. He had talked down dissenters, calmly, respectfully. People congratulated him. His mother and sister had been there watching. As the crowd began to disperse, Plinio reminded everyone of the need for complete secrecy, saying, “This is going to be a peaceful march. But make your spears look sharp and dangerous.”

It was late, and I was starving. So was Alcides, a friend of mine who had been the COMARU treasurer before Plinio. Alcides said he knew of a little shack not far up the road that sold a few things. As we walked, I asked Alcides what he thought of the strike, of Bagua, of the protests. “It is historic,” he said. At the shack, two women were sitting at a table. There were a couple of warm sodas, some cans of tuna, crackers, and chocolate. We bought the tuna and sat at the table to eat.

One of the women asked us, “Were you at the assembly?”

I glanced at Alcides.

“No,” he said. “There was no assembly.”

“But I heard on the radio that Plinio Kategari was calling an assembly.”

“No,” Alcides insisted. “There is no assembly.”

The other woman asked us what we knew about Alberto Pizango. “I heard he had been sneaked into Bolivia,” she said. Later, when they got up and went inside for a moment, Alcides said, “If they did not show up at the meeting, do not trust them. They could offer the information to the police for money or favors.”

After eating, we drove across a bridge in the station wagon and sped back toward Quillabamba. On the way, when Plinio was finally able to get a signal, he made a phone call. He told the person on the other end to get on the two-way radio and call all the communities to let them know that a social action was being planned in a matter of days. “Speak in Machiguenga only,” he said. “The police will be listening.”

When we got out for a bathroom break again in Kitini, I asked Plinio where COMARU was getting the money for cars and gas and other logistical help. Without looking at me, he said something about a group in the US vaguely suggesting that the money was coming from them. A little later, he changed his story slightly, saying that the money was coming from the communities themselves. A few days later, Plinio seemed to open up more, telling me that the mayor of Convención had been providing support and that both the van we took to Andioshiari and the driver had been authorized by Mayor Torres.

We waited for a few days in Quillabamba to see if the demonstration was going to materialize. More than once, I went drinking with Plinio and Alcides. “The government and the oil companies are one,” said Alcides. Evidence seemed to support his claim. For natives, Peruvian as well as Ecuadorian history is full of reasons not to trust the government. As recently as 2008, an oil scandal began after a Peruvian TV station broadcast an audio tape of an alleged conversation between a Peruvian government official and a lobbyist agreeing to help a firm win contracts. The scandal led to the resignation of Prime Minister Jorge del Castillo and the appointment of a new cabinet headed by Yehude Simon, who met often with Pizango.

What’s more, the governments of Peru and neighboring Ecuador, which share the high jungles of the Andes Mountains, have done little to stop companies from behaving inappropriately. A few years ago in Ecuador, one of my sources (an Ecuadorean lawyer who worked as an assessor for a group of congressmen from the Amazon provinces) showed me formerly classified contracts between oil firms and natives. In one case involving the Italian company Agip, the oil company signed a “social contract” with a native community. In exchange for waiving their right to sue, the natives were given, among other things, a referee’s whistle and several cans of lard. The government of Ecuador also allowed the oil giant Texaco to operate with impunity for years. The company’s sloppy practices went unregulated and today thirty thousand Amazon natives from eastern Ecuador are working with Ecuadorean and US lawyers to sue Chevron (formerly Texaco) for over $20 billion. The case has been going on for more than a decade and native backers see it as a milestone.

Natives in northern Peru, where opposition to oil development has been going on for years, are also using novel litigation tactics. After years of mistreatment by Occidental Petroleum, a California-based company that extracted millions of dollars from Peru’s Corrientes region from 1972 to 2000, Indians backed by US lawyers are suing the company for polluting streams and rivers and causing illnesses among the subsistence natives who use the water for bathing, swimming, and drinking. US lawyers are bringing the suit on behalf of twenty-five indigenous Peruvians in a Los Angeles court, alleging that the firm did not abide by Peruvian law and industry standards when they failed to re-inject toxic wastewater safely back into the ground.

In 2008, I went with Lily La Torre, the main Peruvian lawyer working the Occidental case, to interview the plaintiffs in their villages. For days we traveled by truck, canoe, and boat to villages where we met people who were sick with lead poisoning or whose children had died from mysterious illnesses. It was then that I met Tomás Maynas Carijano, a middle-aged Achuar Indian and Apu of a tiny village called New Jerusalem, on the Marañón River, deep in the northern, oil-stained Peruvian Amazon. Apu Tomás—who is the primary plaintiff in the Occidental lawsuit in California—had one of the larger huts in the village. Inside there was an open fire and blackened pots and pans. Looking like a sack of clothes, an elderly woman was lying on a dingy mattress in the corner. “The natives will fight if we have to,” the Apu said through an interpreter. “We hope that the judges will help us before that point.”

The deaths at Bagua transformed the situation in the deep jungle, galvanizing remote communities in protest against what Survival International dubbed “a jungle Tiananmen” and giving credence to the implied threats of leaders like Apu Tomás. Native pressures eventually forced Garcia’s government to scale back the most noxious land decrees. In November 2009, a Peruvian government investigator issued a report blaming the Bagua massacre on two Peruvian military officials.

Back in Quillabamba, before that happened, we were still waiting on Plinio’s big Monte Caramelo march. We were told that a gas facility was to be taken over. I showed up at COMARU headquarters the night before all the Indians were due to arrive and found the place empty except for two men. One was mopping the floor. He told me there was no march. I asked why and he told me to talk to Plinio.

I tried calling Plinio several times that night and got no answer. The next morning I cornered him at COMARU and learned that his bosses in Lima were making progress and that they had called off his solidarity action, but only at the last minute. He got on the telephone and made several calls. I sat outside and listened to him apologize to people, and then I eavesdropped on a staff meeting in which he talked about how he looked bad because some of the people at the meeting in Monte Caramelo were already on their way, having not received word about the cancellation in time. When I finally got him alone for a moment, he conceded that for him personally it was a political loss. “They trusted that it was going to happen,” he said. “But if the government is negotiating, then the battle is won.”