-

- A woman pauses to pick up her shopping bags outside the Sayyida Ruqayya Mosque in the Old City of Damascus. (Jennifer Hayes / CC)

We were late arriving in Damascus, though I can’t remember exactly why. There was traffic coming out of Aleppo, or perhaps we got lost in Damascus, or perhaps the stop for strong, bitter coffee along the way—our driver’s eyes kept fluttering closed—took longer than it should have. In any case, our group of seven American poets, novelists, and journalists was well behind schedule, and there was nothing we could do about it. We drove: desert, scrub-brush hills, then Damascus, a city, with all the requisite noise and chaos. Our two guides, the preternaturally calm Hassan, a teacher, and Fatih, a pharmacist with reddish-brown hair and a broad, welcoming smile, were both from Aleppo, and they didn’t know their way around. It was such a helpless feeling: any corner might represent the correct turn, or the absolute wrong one, and we had no way of knowing the difference. There were no street signs we Americans could read and no one we could ask; between the seven of us, we spoke maybe a half-dozen words of Arabic, and none had ever been to Syria.

We finally made it to the University of Damascus and were wandering around the campus, looking for the right classroom, when some students recognized us—not as individuals, naturally, but as foreigners, likely Americans, possibly the writers they’d been told would be arriving that day. They’d been looking forward to our lecture. They led us to the right building and into a classroom, where we found a handful of students waiting patiently. Everything about it was strange—the harried morning leaving Aleppo, the long meandering drive, the teeming streets of Damascus, even the limpid quality of the sunlight in Syria, golden, unlike any I’d ever seen. Like my colleagues, I was still trying to figure out what I was supposed to be doing here. Another class was about to get started, and so a brief discussion began around us, Fatih and Hassan explaining our situation, apologizing for our tardiness, while some of us milled about, trying to appear professional. Eventually, the professor ceded us the floor, and just like that we had a classroom to ourselves, just us and the students.

The next four hours will rank, I’m certain, among the most moving experiences of my life. We sat on a raised stage in a large lecture room, as the wine-red desks gradually filled. Eventually, there were about seventy students, an even mix of men and women, though many faces changed in the course of the afternoon. Students filed in and out, or clustered at the door, peeking in at the American writers. Each of us read—poems, fragments of stories—and they listened very politely, and then they spared us nothing. Your stories are very nice, they said, but why are you here? How do you explain what the US has done? Why was Bush reelected? What if your brother were asked to bomb us? What did Islam do to you? We’re scared, they said. We’re nervous. My brother and sister are dying. Israel will attack us. America will attack us. This university won’t exist. This city. We’ll be dead. I once lived in Baghdad, and I know I’ll never go back. There are refugees everywhere, even in this room, and we don’t know what the future holds. So tell us, who has power in your country? And why should we believe you? Who let the war happen?

It went on like this for hours.

Finally we left the classroom, and the conversation simply moved with us into the hallway. Women and men, politics and religion—the students wanted us to hear all of it. Students clustered around us, each eager to share his or her opinion, to clarify something that had been said, or to expand upon it. It was impossible not to be impressed by their openness, their excitement and eagerness to share. One young man—a boy, really—brought up women drivers, a relatively new development in Syria, which he considered dangerous, and it was amazing to watch his female classmates pounce on him. These women were fiercely intelligent, and they made mincemeat of that poor boy. He shrank away, and the conversation turned once again: 9/11, Israel, the troubling weight of history, and the war, the war, the war. By the end, I was exhausted. We all were. Our trip had only just begun, and already it felt like we’d been gone for weeks. That night I fell ill and nearly threw up in front of the Minister of Education.

The not-so-simple idea was to take a group of American writers to the Middle East. We were to speak at various universities in the region, meeting with local writers, poets, journalists, and intellectuals along the way. This, I suppose, is what they call person-to-person diplomacy. There is a small office within the Byzantine bureaucracy of the US State Department that sponsors these sorts of things, though the logistics of our road trip through Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine were left to the staff of the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. In nearly every city we visited, either the local American diplomat or one of our hosts would remind us that we were not representatives of the United States government. This was meant to reassure us, but the point was made so often and so consistently that it became a little unnerving. Try explaining the distinction to the students of the University of Damascus. We were representatives of the United States—having attended a few antiwar rallies in 2003 did not absolve us of responsibility.

I knew when I signed up for it that this wasn’t going to be a normal trip. There wouldn’t be a lot of free time. It would be work. It’s a trade-off. On the one hand, you give up a certain amount of independence. On the other, you get access you might not otherwise have, and of course, all of it is happening on America’s tab. I knew (and know) essentially nothing about the region. I speak no Arabic beyond God bless you and Thank you, and I felt that my being invited was a mistake, that I should accept quickly and enthusiastically before someone had the good sense to reconsider.

What the State Department hoped to accomplish was less clear to me. One can’t help but wonder how bleak must things be if Washington has no better ideas than to send a bunch of writers out to Damascus and Amman and Ramallah. I have a very high opinion of the utility of art and literature, but there are some problems that cannot be smoothed over with a well-written short story. Imagine: Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice briefing the president on the grim news from these sundry nations he had hoped to invade someday. They are alone in the Oval Office at the end of another long week, and the president is gripped by a sense of despair. All his plans have gone awry. The Surge is a failure. Iran continues its relentless push toward nuclear weapons. President Bush stares blankly out the window.

“God damn it, Condi,” he shouts suddenly. “Get me some novelists! Get me some poets!”

The day after falling ill, I walked to the Old City of Damascus, slipping easily into the rhythm of those who hurried along its warren of narrow streets and alleys. Now and then I stopped to admire the texture of the place: the curve of a cobblestone path, gradations of conservatism in women’s dress, layers of history stacked, often gracelessly, one atop the other. A letter box painted red—BOÎTE AUX LETRE, read the French; the Arabic below—affixed to the grim face of a blackened stone wall that has stood since the Ottomans. The internet café housed within those walls, and the knock-off perfume sold ten paces away. The crowds that stream by—a boy in a Ronaldinho jersey, a woman in a black chador, a grizzled man in a baseball cap selling pistachios, or toy soldiers, or AA batteries—and the sound of Arab pop music leaking from a passing car. Damascus (or Aleppo, depending on whom you ask) is the oldest continuously inhabited urban center in the world, a fact that is easy to believe when you are face-to-face with it. It is suffused with history, even as it is completely entangled with today’s messiest predicaments. If a cradle of civilization can be said to exist, this city is it.

I made my way to the door of the Grand Mosque and then to its courtyard’s marble patio, where I sat to appreciate the antique dignity of the holy site. There were children playing chase, sliding in their socks across the polished stone, entire families sprawled out in the sun, and a constant, pleasing din. The muezzin’s call came, and some of the gathered crowd rose and disappeared into the hall, but many stayed. The day was warm and bright. I took out the microphone a friend had lent me for my trip and recorded the wash of sounds—the call to prayer, the shouting children, the chatter of stray conversation, the shuffling of feet.

I’d been there for a few minutes when a man approached. He glanced at the microphone and offered me his hand. Was I journalist? I explained I was a writer. He asked where I was from, and I told him. I introduced myself, and he said his name was Murat. He was a Kurd, he said proudly.

“From Syria?” I asked.

“Iraq,” Murat said, and then frowned. My microphone had been on the entire time, and he leaned in now and spoke directly into it: “Don’t. Ever. Go. There.”

Murat’s words hung in the air. Even the mosque seemed eerily quiet as I considered what he’d said. He held his severe expression for a moment, and then another, until it was almost unbearable. Then he broke into a smile. No, no, really, he assured me, everything is fine in Kurdistan, no problems at all. It’s the rest of the country that’s a nightmare. Ha-ha-ha. He thought he had scared me. He had. There are at least one million Iraqi refugees in Syria. They have fled the catastrophe next door and huddle in Damascus, waiting, praying, hoping that the violence back home will somehow end. Iraq is a scary place, and the physical and emotional hangover from the previous day—from the long conversation with students at the University of Damascus—was real.

We chatted some more, and Murat tried to reassure me: he spoke about the beauty of his part of Iraq, the warmth of the people. Saddam is dead, and there will be peace so long as the problems of the south do not migrate to the north. He asked me about the US, about Peru. He told me he’d worked for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, as an interpreter, but, of course, that work no longer existed. He showed me his green Iraqi passport, lately one of the world’s more useless travel documents, and pointed out how he had lied about his occupation: he hadn’t written interpreter, but a word that did not imply any collaboration or dealings with foreigners: worker. We rose and wandered around the mosque, chatting, following the crowds that flowed between the various rooms. We passed a group of women all in black. “These are Shiites,” he whispered to me, in the low discreet tone that one might use in a museum.

I nodded and felt myself blush. It seemed inappropriate to me, this kind of talk, but Murat carried on, unperturbed, and so I followed along as quietly, unobtrusively as I could.

He posed before the green glass tomb of Saladin, the great Kurdish sultan who battled the Crusaders, and I took Murat’s photo with his cell phone. Afterward, as we sat once again at the patio, I asked him why he had come to Syria. He sighed. Tourism, he said, at first, but his heart wasn’t in it. He was quiet for a moment, and then explained that he’d come to register his family on the United Nations refugee list. “If I put my name down now, inshallah, I’ll get an interview next year.”

He’d spent the last hour assuring me everything in Kurdistan was fine, lovely, calm. The people are affectionate, the countryside is breathtakingly beautiful, and there is no war to speak of. They are rid of the homicidal dictator who threatened their culture, their language, their very lives. And he wanted to leave?

“Yes,” Murat said, when asked about the contradiction. He had a wife and two daughters to look out for. He’d shown me pictures. “Now things are all right. But in two years, in three, who knows?”

“Where will you go?” I asked.

He shrugged. Sweden, Australia, Canada, England. Wherever. The world is a big place, no matter that war has a way of shrinking it to the size of a fist, or a stone, or a gun.

“Of course, my first choice is the United States,” Murat said, smiling.

I could do nothing but smile back.

We both knew that wasn’t going to happen.

-

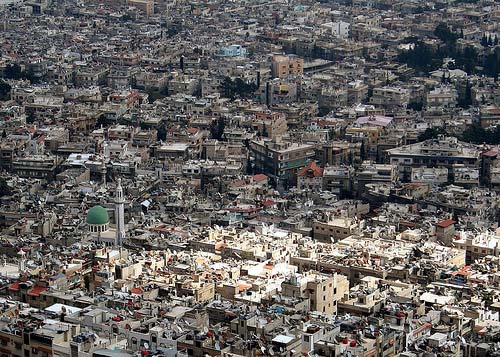

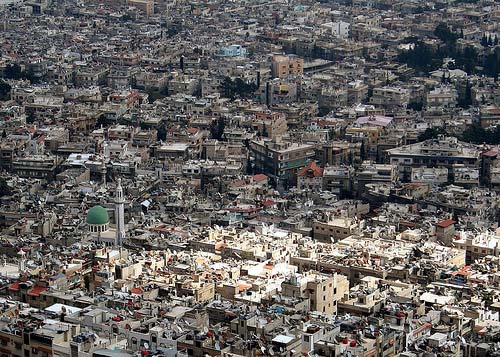

- Damascus, as viewed from Mount Qasioun. (James Gordon / CC)

If there was any purpose to the trip, it was to hear these sorts of things. To feel just a bit of this tension. To meet this man and have nothing to say. To read our little stories, our little poems in a room full of Syrian students and feel helpless and a bit ashamed in the face of their fear. The war’s American death toll has exceeded four thousand—but in the Middle East the effects are multiplicative. A cataclysm is underway, exploding outward in waves across the region. People’s voices here crack when they speak of it. The dead can be tallied up, of course, however politically inconvenient it may be to do so: this many American soldiers, that many Iraqi insurgents, this many civilians. This many Sunni, and that many Shia. The refugees, the internally displaced, the millions of ordinary citizens driven from their homes—these, too, can be counted. But the psychic toll is impossible to assess, is not confined within any borders, and there is no comprehensive way to measure fear.

We went out with some local writers that night, to a cavern of a restaurant hidden (or so it seemed to me) somewhere in the Christian quarter of the Old City. The war was on my mind. How strange then to find, inside the restaurant, a celebration underway, with music and shouting and smoke, such that my sour mood seemed misplaced, even selfish. It was early yet, but folks were already dancing and singing, and so when a glass of liquor was offered, although I still wasn’t feeling well, I accepted.

One of the local writers asked if we’d heard the news. The news, he said, with a cherubic smile, raising a glass of araq in a toast. Syrian television was reporting that President Bush had been caught with a prostitute and that she was going to testify against him. She was young, beautiful, fearless. Our friend beamed.

The American writers clinked glasses, all of us a little stunned. This was undoubtedly good news. Thrilling news. The cabal’s last justification vanishes: their claims to piety and moral superiority disappear, the facade crumbles, and we are free. I’ll admit the news excited me, that I longed to see President Bush quaver, stammer an excuse, that I longed to see him subjected to the humiliating spectacle of sex scandal. Not out of prurient interest, but out of pure spite. The man’s general incompetence should be scandal enough, but, unfortunately, it often takes a salacious accusation to crystallize public opinion.

Our mood had changed dramatically, and I felt buoyed. The writer sitting across from me was like a dozen people I know in Lima: ridiculous, charming, brilliant. He smoked without pause, kept my glass full, and when I turned down a bite of some kind of spicy raw meat, he looked genuinely disappointed. I tried to explain that I’d had the same appetizer the night before and it had nearly killed me, but there was no convincing him. “Are you novelist?” he asked.

I nodded.

“If you are novelist, then you must eat this.”

He leaned in to explain. “Daniel,” he said, choosing his words very carefully, “a novelist is like God, but against God. Every day in my life I have twenty mistake. And is good. I love mistake. I want to drink the life!”

From across the table, Fatih shot me a look, part maternal worry, part implicit reprimand. Don’t eat that, she seemed to say.

As I hesitated, the writer laughed maniacally, then ate the raw meat himself.

The music got louder, everyone shouting, and the entire place seemed drunk and thrilled to be alive. I got up to record the music—lovely, beguiling music—and when I returned, Fatih informed me that the singer was in fact, quite mediocre. Appallingly so. And it did not matter. We kept drinking, offering toasts to prostitutes who testify against presidents. The restaurant sang in one voice.

Later, another table called me over. They were a mixed group of male and female doctors, celebrating a birthday or something. A table of men in suits, their ties loosely knotted, and women in glamorous, sparkling dresses—everyone glassy-eyed, beautiful, happy.

“What are you doing here?” one of the men asked. He pointed to my microphone.

I tried to explain—American writers, reading tour, goodwill, etc.—but of course, it all sounded a little preposterous.

“Will you tell the Americans we are not bad people?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said.

He smiled laconically, as if the very notion sounded cute to him. He taught me a few “Syrian greetings,” which I repeated loudly to the table, hoping to spread some goodwill. Naturally, these turned out to be coarse Arabic come-ons, and the table erupted in laughter.

“You’ve heard the news,” he said, suddenly serious. “About your president?”

I nodded. He slapped me on the back. “Very good,” he said.

“We’re going to see the Mufti tomorrow,” I said after a while. We’d just been told that the Mufti, something like the bishop of Syria, had agreed to receive us the next day. We’d been told to expect a solemn encounter with a spiritual man.

“The Mufti? Really?” The man was drunk and happy. I had to lean in close to hear what he said next. “Very good. He’s a nice man. You can ask the Mufti anything,” he said. “Even about fucking.”

Back at the hotel, Tony, one of the writers in our group, ran to his laptop to verify the news. I don’t think I’ve ever been so hopeful waiting for a web page to load. We checked CNN, the New York Times, the Guardian. Nothing. We despaired. Finally, at the Washington Post we found a small note, and we began connecting the dots: some midlevel administration official had preemptively resigned, so as to avoid publicity surrounding the DC Madam case. This was all. No sex scandal that would bring down President Bush. No Monica-gate 2007. It had seemed too good to be true, and it was.

We slumped in the couches, deflated. To cheer us all up, Tony played an MP3 of his son’s band playing a song the boy had written. It was catchy number called “Bush Sucks.” We laughed and congratulated Tony, while Fatih sat with us, listening, shaking her head. When it was finished, she said, “If you write a song like that here . . .” and she trailed off. Then she dragged a long, elegant finger very slowly across her throat.

One of the sadder consequences of the Iraq catastrophe is how it has undermined the legitimacy of those who were pushing for democratic reforms in countries such as Syria. Try selling democracy if the only regional example is a country breaking up along sectarian lines, a place where each day’s news begins with a death toll. Autocracy starts to look pretty good by comparison. The US decision to isolate the countries we don’t get along with seems especially misguided; in the case of Syria, we have a lot to talk about. Democratic presidential contender Barack Obama was attacked by members of his own party for the mere suggestion that it might be a good idea to talk to these countries. I find this baffling. How much worse do things need to get before it becomes acceptable to offer an alternative approach?

Still, Syria is hardly a model of openness. There are periodic crackdowns on writers, journalists, and folks who fit in the broad category “dissidents”; just a few weeks after our visit some democratic activists were imprisoned. There’s a hefty cult of personality being constructed around President Bashar al-Assad, whose ubiquitous portrait frowned at us in virtually every office, reception area, public park, traffic circle, or government building we visited. Most of our public appearances, and even our private meetings with government representatives, were recorded, presumably for Syrian state television, and who knows how these images were manipulated, or exactly what spin our visit was given. We took the risk—better that than the alternatives: silence and isolation.

Ahmad Badr al-Din Hassoun, the Grand Mufti of Syria, met us in his elegantly decorated sitting room the following morning. He was in his forties, with a neatly trimmed beard, dressed in a pearly white head wrap, a nicely tailored slate gray robe, and matching socks. Not long before our visit, he’d sat in the same room with Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, during her allegedly controversial trip to Syria. He exuded warmth, sat smiling and nodding while his attendants served us tea. I did not ask him about fucking.

Already in the course of our trip, for reasons of protocol, we’d been subjected to a few harangues from bureaucrats, university administrators, and representatives of various religious communities. Given all that, I wasn’t exactly hopeful about the Mufti, but my fears were completely unfounded. Speaking through an interpreter, al-Din Hassoun offered his vision of Islam, politics, and the future of the region. He was funny, engaging, hopeful, and humanist. “People of faith and intellectuals,” he said at one point, “let us agree that if tomorrow we destroy Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Wailing Wall, or Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, God will not be as angry as when we kill a single child playing outside his home. In the eyes of God, this child is more important.”

He described the letter he had sent President Bush in the days before the bombing of Iraq began in 2003—“The Middle East gave the world its great prophets—is our compensation for this gift of light only fire?” He spoke warmly of an American rabbi who had been his guest in Syria not too long ago—and joked that he’d had to send a video of the rabbi’s speech at a Damascus mosque to the US, proving to the rabbi’s friends that it actually happened. No one in the US believed Jews were welcome in Syria.

I liked the Mufti, and I thought of him then as a fundamentally good man. I still do. His vision served as an antidote to the fear we’d witnessed at the university; he articulated hope with conviction. He had the winning smile and polite bearing of a diplomat, though later it struck me that nearly everything he’d said sounded as if it had been scripted by a politically correct ecumenical council in Santa Fe. Nearly everything, but not all. When he was finished speaking, he invited us to ask him questions. I thought about Murat, the Sunni and Shia worshipers mingling effortlessly at the Grand Mosque, and the dread I’d heard the university students express. It all seemed related somehow. I asked the Mufti if there was any chance that the Sunni–Shia violence engulfing Iraq could spread to Syria.

“As soon as the occupying forces leave, the different groups in Iraq will reconcile, because they are a single family,” he said. I would love to believe this, but it is self-evidently untrue. All that blood being spilled in Iraq—it will stop the very moment the American soldiers leave? Inshallah. The Mufti invoked 1948—the year of the founding of Israel—as the beginning of the region’s troubles, a constant refrain in the Middle East that does not accept any measure of Arab responsibility for the current situation. It recalled for me the kind of thinking I’ve heard so often in Latin America among the unreconstructed radical Left: every political crisis, every economic injustice, every pothole in every street, and every sick child languishing in the hospital is the fault of American imperialism. It’s such a seductive line of thought because it provides such an obvious solution. At my first question, the Mufti’s clear thinking became a little muddled. Suddenly he was invoking the 25,000 mercenaries brought by the Americans to destabilize Iraq, the ten al Qaeda operatives who had confessed to being trained in Tel Aviv by the Mossad, the conspiracy to murder Princess Diana because her boyfriend was Egyptian. He had veered off—though the calm tone of his voice never wavered, the content of his speech was suddenly quite different. Nor was this the only contradiction in his discourse: al-Din Hassoun, for all his stress on the importance of separating religion and the state, was himself a government appointee.

Our conversation lasted about an hour, and when we were done, we posed for a few photos. Grand Mufti al-Din Hassoun stood flanked by a few American poets and writers, beaming like a proud father. We said our goodbyes and went out to the van waiting to take us to Jordan.

Fatih pulled me aside as we walked. She would accompany us to Amman, then leave us. She had a special favor to ask me, she said, and it was very important. Would I do it?

“Of course,” I said.

“Write about Tel Aviv. I want you to tell me what it’s like. The city—what does it look like? The people—how are they? How do they talk?”

Tel Aviv, she explained, is rarely mentioned in Syrian media, and the city itself is never shown. As if it didn’t exist at all. An interior shot might appear on television now and then, but she longed to know more than that.

I told her I’d do my best.

“Good,” she said. “Write me an e‑mail, but when you do, don’t mention Tel Aviv by name. Just say the city.”

-

- The Tel Aviv shore, at sunrise. (Shayan Sanyal / CC)

We arrived in Tel Aviv on a night when a million people gathered in the center of the city to demand that Prime Minister Ehud Olmert resign. A report on the 2006 war with Hezbollah had just been released, and this firestorm was the predictable result. I was raised to support demonstrations, to respect the powers of masses who take to the streets, but this was one protest I found difficult to get behind. From talking to people, this was the message of the march, as I understood it: We need a new prime minister—soon—because there is a war around the corner with Syria or Iran or Hezbollah or perhaps even all of them at once and we can’t have this incompetent running the show when the shit hits the fan. It was impressive, I suppose, in that one rarely sees such bald expressions of realpolitik coming from the masses, but the underlying assumptions—war, war, war—were disheartening and sad.

The next morning, I awoke in a seaside hotel that looked out over a boardwalk and a beach and the Mediterranean, a sheet of electric, eye-popping blue. Though it was Friday—the Jewish and Muslim holy day—you wouldn’t have guessed it. Couples strolled along boardwalk hand in hand, there were joggers and rollerbladers wearing iPods, and I spent the morning walking up and down the stretch of beach wondering how I ended up in Miami.

Away from the boardwalk, Tel Aviv reminded me of Lima, and this is what I wrote Fatih in my letter: no dominant architectural style, a curious, often unsightly mishmash—Art Deco, modernist, classical, here and there a nod to the Middle East. Visual cacophony. A city built facing the sea. The Israeli writer and film director Etgar Keret explained the eclectic nature of Tel Aviv to me this way: The city, as it is today, was built by Jews that came from many dozens of nations. Think about that diversity of linguistic traditions, cultural mores, and visual cultures. They arrived here and made a city. And, Keret added, it was not built with posterity in mind, but came of age under the constant threat of annihilation. Why bother with city planning if in five years the city, the country, and the Jews themselves might not exist?

In the afternoon, I walked around Jaffa, the old Arab city that Tel Aviv has since overwhelmed, on a tour of sorts with Antonio Ungar, a Colombian writer who had married a Palestinian woman. He showed me the old houses, refurbished and transformed into condos for rich Israelis as the area is slowly gentrified. He explained the slow encroachment of Jewish settlement on what had previously been a thriving Arab port and described the orange groves that once stood, the stands of olive trees razed by the Israelis. This is the way love works, I suppose: the stories of each become the story of both, and it was astonishing to hear this tragic Palestinian tale recounted in the elegantly accented Spanish of a Bogotano. “It was such a beautiful place,” Antonio said, with such conviction you’d think he’d seen it himself.

-

- The streets of Ramallah. (Tom Graham / CC)

The image I had of Ramallah was from Arafat’s last days, when the Palestinian leader was holed up in his compound, under siege from the Israelis. I thought the entire city would be bombed out, demolished, but of course this wasn’t the case at all. The day we visited, there was a movie being filmed in the central part of the city. A few young men sat on the tiled roof of a two-story building, baking beneath the sun, while a curious crowd gathered below to watch the actors. The streets were full of people, and traffic inched along. There were bookstores, gaudy billboards for cell phones, and a Starbucks—though upon closer inspection, it was a knockoff called Stars and Bucks. Later, as we drove to our reading at Birzeit University, our host pointed out Arafat’s compound. It had been rebuilt.

I was surprised by the extent to which a Middle Eastern daily life resembled most other lives. People hurry to work or to school, to see friends or lovers. They negotiate the extraordinary circumstances they live with, and in doing so, make them ordinary. At our reading, a student named Laila described her daily commute from East Jerusalem to the West Bank. Were it not for the checkpoints, Ramallah would be less than thirty minutes from Jerusalem, but depending on the mood of the soldiers on any given day, the trip can take anywhere from two to six hours. I wonder how many American students would overcome similar hardships to get to class. But Laila didn’t want to talk about checkpoints. She felt great sympathy for the Israeli soldiers, she told us. They were so afraid, and the militarized interaction between Israelis and Palestinians seemed almost perfectly designed to drive both sides insane. In any case, those would not be the memories she would carry with her from Birzeit. She was just like any twenty-year-old student, and she would remember her friends, the good times, laughter.

After our reading, we were supposed to have lunch with a few local journalists and writers. In most places, organizing a lunch wouldn’t be such a big deal, but in the West Bank, in the Palestinian territories, everything is complicated. The problem was that one of the invited guests worked for the Ministry of Culture of the Palestinian National Authority, which, since 2006’s democratic elections (and until Mahmoud Abbas dissolved the government following the civil war in Gaza) had been run by Hamas—a group on the US State Department list of terrorist organizations. So our potential lunch guest was, by the transitive property of myopic diplomatic fiat, a terrorist. We did not represent the US, and yet here we were, having our dialogue hampered by the government’s rules.

All week long the International Writing Program had been attempting to resolve the issue. This man was precisely the kind of person we felt we should be talking to, but we’d been put in the awkward position of having to rescind his invitation. That hadn’t sat well with anyone. E‑mails went back and forth, some hostile, some hopeful, and as we left Birzeit, we were optimistic that at least some of the people we’d invited might show up. The restaurant was on the outskirts of town, and we drove through the bustling center of Ramallah and then along hillside roads through the stark beauty of high desert landscape—the bare rock glowing in the sun, a glaze of dust along the horizon. We could see the Israeli security fence—a wall, actually—a thick, concrete scar on the land or, more precisely, a perverse memorial to those on both sides who have attempted to make peace and failed. I understand why some people would rather not think about this region and its endless complexity, why some would just wish it away. We forget, even here on the ground, that there is life outside of politics, a Holy Land beyond one thousand years of bad decisions. We forget about the people.

At the restaurant we were led to a large, tented, and airy dining room where, in anticipation of our event, the waiters had set up a very long table with flowers in the middle; there were two plastic flags—the American and the Palestinian—crossed in a symbol of friendship. It was just our group and a few administrators from the university, and so the flags in particular looked rather sad. There were about ten seats too many. After a few words from our hosts, the waiters began dismantling the spread. A much smaller table was prepared, and everyone stood uncomfortably around it, not really knowing what to do. They removed the flags, and we sat.

We kept expecting someone else to show, but no one ever did.

The food was delicious, and we ate it alone.