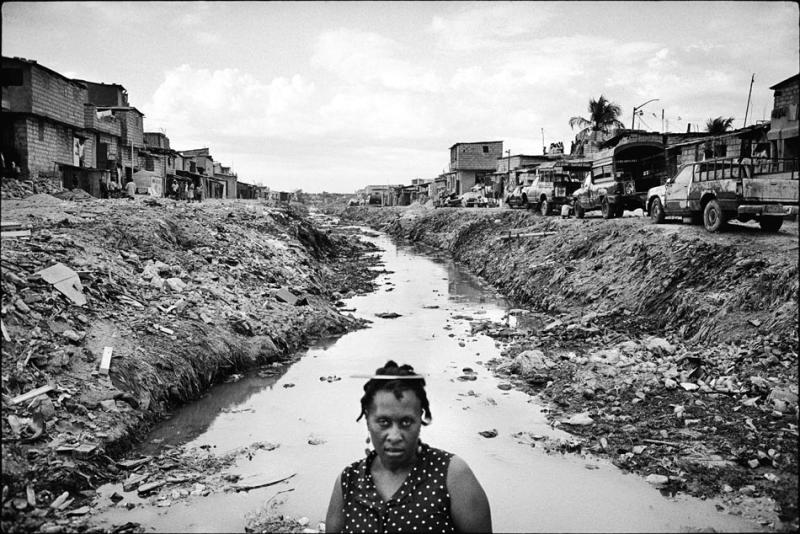

After the last of four back-to-back hurricanes pummeled Haiti in August and September 2008, mountains of garbage, mud, raw sewage, and debris were left behind, clogging the streets of Port-au-Prince. A spate of unbearably hot and humid days followed, making the city’s narrow confines feel even more claustrophobic than usual. In the neighborhood of Carrefour Feuilles, a sprawling slum of one-room cardboard and tin shacks that look like they’re about to collapse, that’s exactly what happened.

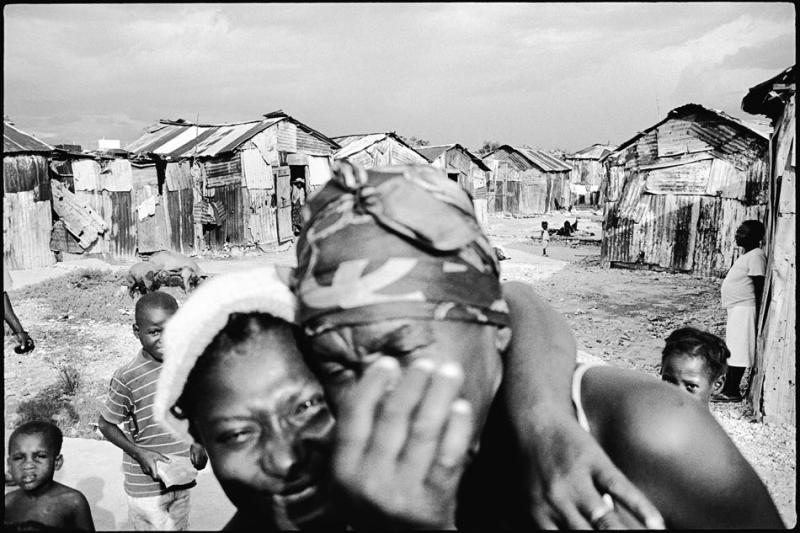

When Hurricane Fay came unannounced in the middle of August, Marie Camel’s home, built haphazardly on a hilly unpaved street, quickly flooded. Marie was forced to climb on the roof for safety. By the end of the day, the storm had washed her entire block down the streets of Carrefour Feuilles, leaving many people homeless.

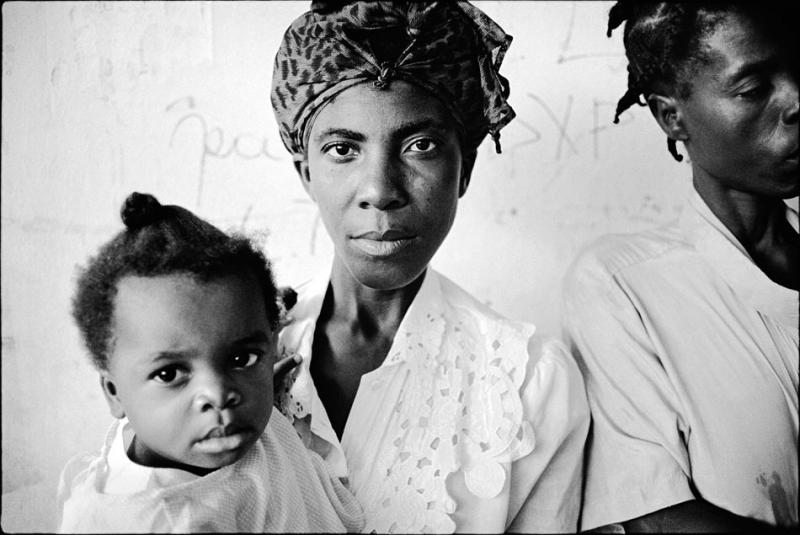

Marie now sits slumped against a metal folding chair, her back to a sputtering industrial fan blowing warm air around a warm room. She is twenty-five years old and has been wearing the same clothes since she fled and took refuge at this shelter: a pair of rubber sandals and a light sleeveless cotton dress with no bra. She doesn’t seem to really need one; her breasts are so small and sagging from feeding her eleven-month-old daughter, Jacqueline, that they are almost nonexistent. In fact, Marie herself is so thin and fragile that one might look right through her, if not for the intensity in her large black eyes—and the delicate film of sweat that covers her body, making her glow.

Almost two years ago, Marie discovered she was pregnant. She recalls not caring much for the father of her baby but being happy about the news nonetheless. But once Jacqueline was born, Marie found herself feeling perpetually worried. “I couldn’t afford to buy food or medicine, and little by little, my baby stopped growing,” she tells me, cradling an imaginary tiny baby in her arms. The real Jacqueline is elsewhere in the building, being fed formula by a nurse. Her daughter’s stunted growth is a telltale sign of infant malnutrition, though Marie hadn’t understood the gravity of it back then.

“Eventually, I saved enough money to bring her to the hospital to see the doctors and they gave me many pills for her, but those didn’t help. Then I brought her to the Doctors Without Borders neighborhood clinic. They treated us well, and for free. But by that point, Jacqueline was sick with diarrhea, malaria, and fever. Now the problem is with her lungs; I was told there’s something inside them that’s making her sick.”

That something is pneumonia. By this point, Marie understood that Jacqueline’s life was at risk because of it, but she felt there was little she could do to help her child. “I can just pray to God that she gets better,” she says, “and hope that I don’t end up having another baby again.”

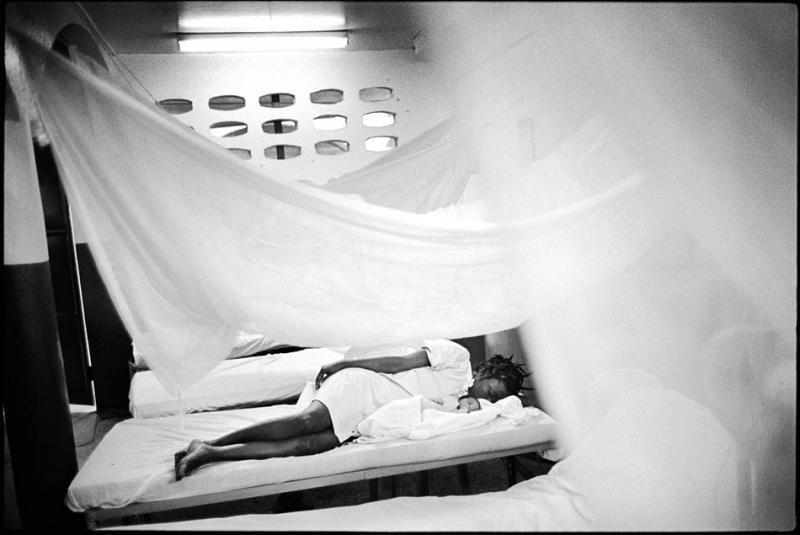

These days, Marie and Jacqueline are staying at APROSIFA, a small nonprofit women’s shelter and clinic located in the heart of Carrefour Feuilles. They share a large room crowded with beds, a TV set, and a single upright fan with about three dozen other women, also left homeless by the storms. Downstairs is where the babies nap on top of carpets and secondhand sheets. Sometimes, during the day, they cry in unison while their young mothers stare at them, helpless, because their drained breasts have no more milk to give.

Twice a day, the matronly staff at APROSIFA give the women and their babies the most basic thing they’ll need in order to get their lives back on track: regular meals. The menu is simple but substantial; it’s often a combination of grits, boiled plantains, lentils, and legumes, mixed in with a lot of white rice—the bedrock of the Haitian diet. The nurse on shift doles out medicines to those who need them, and a volunteer instructor spends a couple of hours each afternoon teaching the young women how to read and write.

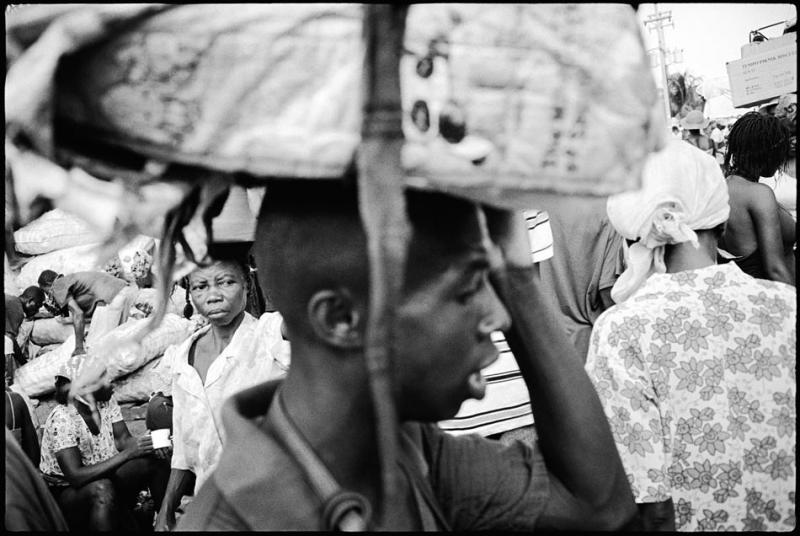

During her five-week stay at APROSIFA, Marie says she’s had plenty of time to think about work and life. “I went to school until I was seven years old and then I had to work in order to help my mom,” she recalls. “I didn’t get the chance to think about what I wanted to be when I grew up. I still don’t know. My mother sold used clothes at the market, so I always thought that’s what I would end up doing, too.”

Marie grew up in a small subsistence farming community in the Central Plateau, a remote mountainous region near the border with the Dominican Republic. Aside from selling pepe (the dregs of Americans’ used clothing), Marie’s mother and her two sisters harvested sugar-cane and sometimes worked as cooks for a few better-off families in their village. Like many other girls from peasant families who had to start work at a young age, Marie often dreamed of leaving the countryside. She wanted to be in the big city, go to school, and find a good and hardworking husband. So not long after puberty hit and she felt the surge of courage that came with it, Marie packed her bags and took the twelve-hour tap-tap ride into Port-au-Prince.

“I like living in the city,” says Marie now, somewhat unconvincingly. “There’s barely any work in the provinces, and at least here in Port-au-Prince I have the option of finding a job someday.” Her friend Lubnia, a sixteen-year-old new mom who also ended up at the shelter after the hurricanes, chimes in. “This is the best place to live in Haiti.” She pauses for a couple of seconds, then sighs deeply and says, “unless you’re able to leave Haiti, in which case, you shouldn’t want to stay here.”

There hasn’t been an accurate census in Haiti in decades, but it is clear that an ever-growing number of unemployed and hopeful young people like Marie and Lubnia leave their homes in the countryside each year, looking for opportunities in the capital. But once they arrive in overcrowded and chaotic Port-au-Prince, they realize that life there doesn’t necessarily get any easier. “My greater hope is to make it to the United States,” says Marie. Lubnia nods quietly in response, but she’s enthusiastic. “Everyone says they have the best doctors there, and I’d be able to send money to my family once I get settled.”

For as long as these two young women have been alive—and, in fact, since the first Duvalier dictatorship in the fifties—Haiti has been on the verge of disaster. From its modern history of brutal dictatorships, coups d’etat, foreign interventions, and crippling debt to its chronic poverty, high rate of unemployment, and almost complete lack of infrastructure, the nation has been a hothouse for poverty, a case study of what pundits call a “failed state,” a nation with an ineffectual and corrupt governing body that can’t even provide its largely destitute populace with the most elemental of services, rights, or protections. The label has been used so widely in reference to Haiti, in fact, that Haitians themselves use it freely when speaking about state corruption, the lack of clean water and electricity, or even the government’s lack of response to the hurricanes.

As if things weren’t difficult enough, since the beginning of 2008, life for average Haitians has been growing exponentially worse. The prices of basic food items like rice, cornmeal, oil, and beans in Port-au-Prince have gone up by more than 50 percent; in northwestern Haiti, the poorest region in the country, prices rose by an alarming 75 percent last year. The legal daily minimum wage in Haiti is currently $2.02; lower even than what it was in 1970 during the dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier.

Not surprisingly, women and their children have had to bear the brunt of Haiti’s hardships. Well-educated women such as Michèle Pierre-Louis, who became the country’s first female Prime Minister amid last year’s storm swells, can enjoy prominent roles in Haitian society. But for the majority of women, roles are limited to domestic work, sex work, subsistence farming, and selling meager supplies at the street market. In turn, children often have to work to help their mothers. Some children even end up being sold, or given, into slavery. The most recent United Nations study on restaveks (the “ones who stay with,” in Creole), found that more than 300,000 children work as domestic slaves in Haiti. Most of these children are girls as young as four years old who were given up into slavery by their parents in the hope that they would at least have food to eat, or a chance to move to the city and go to school.

But with Haiti’s state education system as underfunded as it is, attending school remains an unrealized dream for the majority of impoverished Haitians. A private elementary or high school can cost up to three hundred dollars a month, a fortune for a mother who is likely to earn only a dollar or two a day. There is currently a growing movement of improvised schools or not-for-profit trade institutes that are being organized by women’s groups like APROSIFA, or by development aid projects such as World Vision and USAID. But these schools suffer from lack of space, materials, and funding to pay teachers, and are found only in the larger cities.

Access to adequate healthcare is another basic right that the state has failed to provide. Hospitals are without medicine, equipment, supplies, and even electricity. Port-au-Prince’s general hospital has managed to survive without funding for the past four years by relying mostly on patients’ fees. Protests and strikes by doctors and nurses are common. But even when doctors are present, those who require surgery must provide gas for the generator to ensure there will be power for the entire procedure.

Lubnia had heard the line at the general hospital was nearly impossible to penetrate unless she was willing to pay a small bribe. One day last fall she took a tap-tap from Carrefour Feuilles to downtown Port-au-Prince with a little extra cash in her pocket, ready to pay up. But she couldn’t even get near the gate; the hospital was closed to the public due to a nurses’ strike.

“I needed to bring my sixteen-month-old baby boy to the hospital because he was sick,” she says, the fan still blowing hot air behind her, Marie still sitting by her side. “Pierre had an abscess on his arm and he needed to see a doctor fast, so I decided to take him to one of the free clinics. They cured the infection, but told me that he had low weight.” Lubnia was sent home with a simple message: to feed and take better care of her baby. “And that’s when I knew I couldn’t do it on my own, I needed someone to take care of us both.”

Lubnia and her tiny son, Pierre, have been staying at APROSIFA for the past four months. Like Marie and Jacqueline, they arrived here shortly after the metal shack they called home fell apart in the rains. And like the rest of the mothers at the shelter, they’ll have to leave when their six months are up. “When we get ready to leave, the shelter will give us a small loan to help us start our own small businesses selling food or pepe at the market,” says Lubnia, smiling. She appears to be ready for the big shift and for a life to be lived outside of these walls. But Marie’s eyes glaze over as Lubnia speaks; she’s due to leave even sooner, and Jacqueline still has a way to go before she is in good health. “When it’s time for me to go,” says Marie, “I guess I’ll have to get back to doing what my mother and sisters have been doing all along.”