In the fall of 2015, as Europe scrambled to address the wave of refugees crossing into the continent, German chancellor Angela Merkel claimed the moral high ground when she announced that Germany would take in nearly 1 million asylum seekers. This would have been a dramatic gesture even without the backdrop of nationalism flaring up in Europe or the xenophobic rhetoric that was poisoning the presidential campaign in the United States, a country whose historical exceptionalism is based, in large part, on the influence of refugees.

Then history pushed back: Fear and loathing won the presidency, resulting in an administration that’s the closest this country has ever come to a totalitarian state. Terrorist attacks at the Bataclan Theater in Paris and the Christmas market in Berlin—along with more violence involving asylum seekers in Germany—have pushed German public opinion toward self-preservation. As a result, Merkel, hailed as “the last defender of the liberal world order,” has been feeling the pressure (it is, after all, an election year in Germany). And while the German government ultimately delivered on its promise of asylum to more than a million, it has also pivoted toward a harder stance in an appeal to conservative voters. The numbers bear this out: In 2016, nearly half of 700,000 asylum requests were rejected, resulting in about 80,000 people either leaving voluntarily or being deported—twice as many as in 2015, and likely to increase this year.

A couple of fundamental questions we were asking ourselves in 2015: What was the lived experience of this crisis? And what did the longer arc of a new life in Germany look like?

These were questions for immersive journalism, a tenet of which is to accumulate revelations in real time, rather than filling in the backstory through clips and footage or others’ memories—the kind of longitudinal storytelling that requires a writer with plenty of time on the ground. The art lies in observation: How a subject’s body language changes when he finally becomes comfortable with being a subject; where the deeper mysteries are behind the dazzling first impressions of a city and its people. What can the writer observe while living a story instead of just reporting it?

With all these questions in mind, we set in motion one of our most ambitious editorial projects to date: one year, two reporters telling different sides of the same story. In one, Laura Kasinof chronicles the assimilation of a Syrian family in Berlin as they navigate a maddening bureaucracy to find help for their son, paralyzed by a stray bullet near his home in Idlib province, whose chances for recovery can only be found in Europe. In another, Ben Mauk tells the story of a village transformed by an influx of refugees—by a ratio of eight to one—who were assigned to it under Merkel’s asylum prerogative. The story is a deeply reported, literary group portrait—a small town’s bildungsroman of sorts, in which we can observe how a community changes as its values are tested.

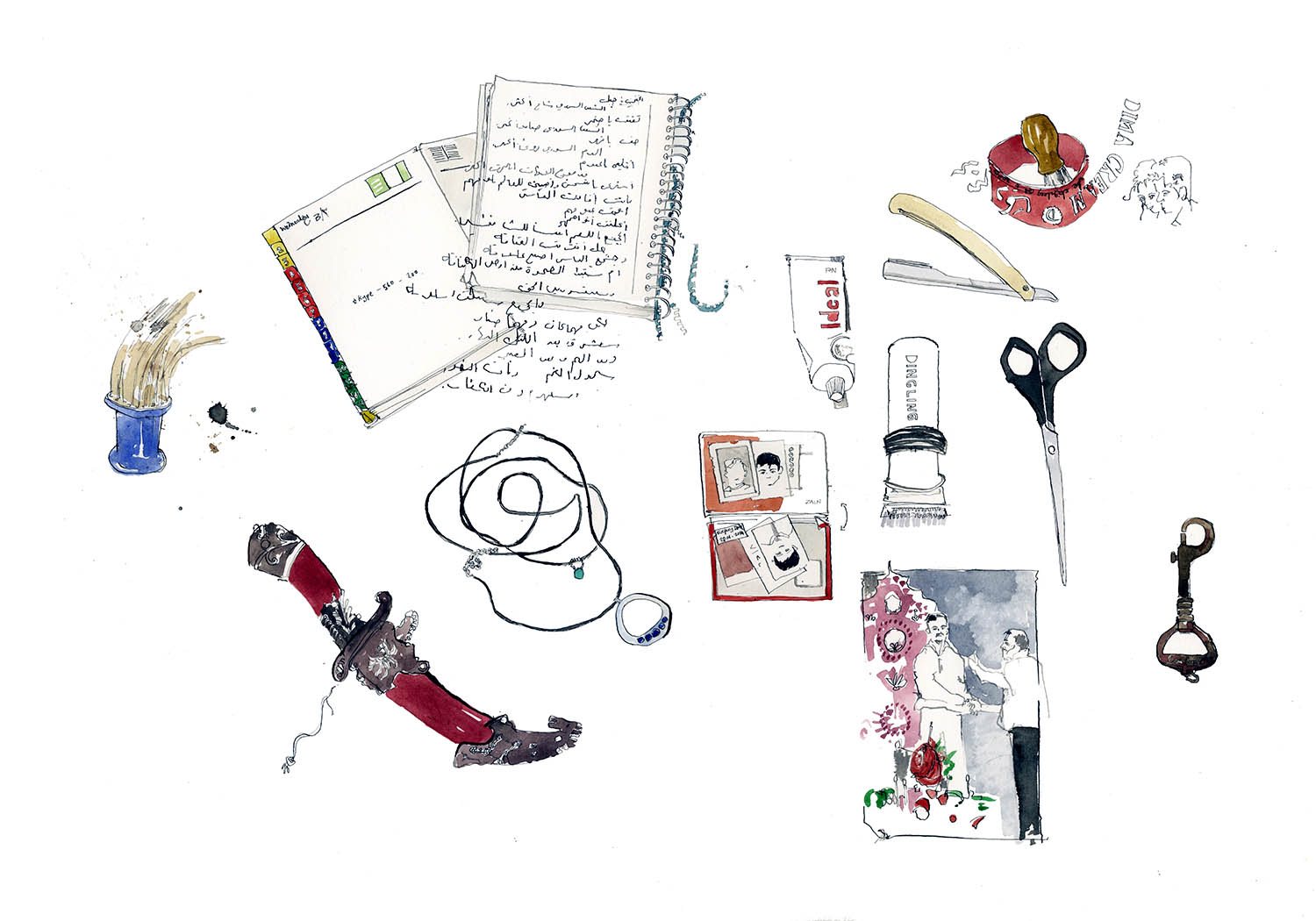

The project is made whole by two additonal features. The first is George Butler’s illustrated prelude, set along the Balkan Route in Belgrade, Serbia, where, in the days he visited, a cold snap threatened the lives of the couple thousand refugees stranded in makeshift shelters behind the city’s main train station. The bridge between the reported pieces is Diàna Markosian’s photographic collaboration with Milad Akhabyar, an Afghan boy whose transition into German life is documented through his own mixed-media Polaroids, in which his illustrations reveal an emotional subtext to the mundane details documented in the pictures themselves.

Altogether, these stories—told visually and through prose—help articulate the themes that bind the migrant’s perspective to the German’s, that connect the individual experience to the universal. Thus, the conversation about the migration crisis is deepened in a way that only immersive work can do.

Altogether, these stories—told visually and through prose—help articulate the themes that bind the migrant’s perspective to the German’s, that connect the individual experience to the universal. Thus, the conversation about the migration crisis is deepened in a way that only immersive work can do.

The intended effect is not unlike what Butler himself has experienced since returning from Belgrade. While there, as is his method, he painted in situ, conversing with his subjects while he worked. Bonfires were fueled by rubber tires and plastic and railway sleepers—just about anything that would burn, a toxic smoke saturating everything. Since then, Butler says, “every time I put my pen on the paper, and make it wet again, this unbelievable, dense smell comes off the page. So you can imagine what it’s doing to the people living there.” That visceral impact, the residue of experience, is what great storytelling in any medium hopes to achieve.

This project would have been impossible without the generous support of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, an organization we have been partnering with for nearly a decade. We are deeply indebted to them for helping us develop crucial stories of international concern, ones that emphasize our commitment to journalism as a vital public service.