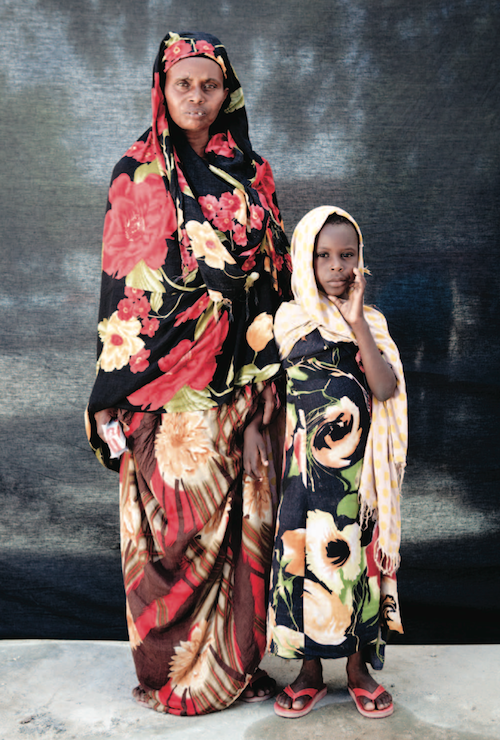

- Isha Mohammad Adan, forty-eight, and her daughter Fartun Hassan Ibrahim, five, fled to Mogadishu when al Shabaab took over their village—seizing houses and farmsteads, raping women and stealing livestock. In three weeks since arriving in the refugee camp in Boondheere district of Mogadishu, they had received no aid from the government. Photo by Jason Florio

In spring 1985, with everyone’s expectant parents sweating and wedged into the auditorium chairs, it was my appointed task to kick off the school’s year-end performance by plinking out the opening strains of “We Are the World” on the music teacher’s Casio keyboard. My classmates swayed on the risers, meaningfully intoning every line, doing their best to mimic the video we’d all seen a thousand times on MTV. For close to two months, the song had been inescapable—and we all knew the complicated story of its creation.

It began in October 1984, when British rock singer Bob Geldof saw a BBC broadcast on the spreading famine in Ethiopia, in which presenter Michael Buerk described the suffering of malnourished children—their slatted ribs showing, their stomachs distended—as “the closest thing you get to hell on earth.” Geldof had a pure impulse: record a hastily penned song (“Do They Know It’s Christmas?”) with British Isle pop stars and then send the proceeds as famine relief. It was such a simple idea that Lionel Richie, Stevie Wonder, and Michael Jackson took it up on this side of the Atlantic with “We Are the World.” By that summer, the efforts were combined for a daylong telethon concert: Live Aid.

Many years later, Bono, the lead singer of Irish rock band U2, would recount how he had gone almost directly from Live Aid to spend six weeks at a food station in northeastern Ethiopia. “In the morning,” he recalled, “as the mist would lift, we would see thousands of people walking in lines toward the camp, people who had been walking for great distances through the night—men, women, children, families who’d lost everything, taking their few remaining possessions on a voyage to meet mercy.” But one morning, a man approached him with a boy in his arms. The man was asking Bono to take his son back to Ireland. “Will you take my son?” he was saying. “Please, he would be a great son for you.” It was that moment, Bono says now, that he understood that Westerners bore a greater responsibility than making occasional donations, that you couldn’t save the world “with a few records and concerts.”

But back in my junior high auditorium, we were swept up in a cause—and it carried over to Live Aid, Farm Aid, Hands Across America, and a string of other outpourings of the late Reagan era that felt good but accomplished little. As recently as last year, former employees of Band Aid were arguing over just how much aid money wound up in the hands of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, then working to overthrow the Ethiopian government. Band Aid’s former field director insists it wasn’t more than 20 percent. One of the rebels, who told the BBC that he used to attend meetings with charity workers and pose as a merchant, estimated that more than 90 percent of aid money went astray.

All of this came rushing back to me in August, when the devastating story and photographs by Jeffrey Gettleman and Tyler Hicks appeared on the front page of the New York Times. The article led with the news that the anti-government Islamist group al Shabaab, which controls much of southern Somalia outside of Mogadishu, was preventing famine-stricken refugees from fleeing across the border into Kenya. Al Shabaab had set up a cantonment camp, Gettleman reported, where they were imprisoning displaced people—and leaving “more than 500,000 children on the brink of starvation.” But what we could do was less clear. The United States had tried intervening in Somalia, near the outset of its civil war, culminating in the Battle of Mogadishu, during which eighteen American soldiers were killed in action, including several Black Hawk crewmembers, whose bodies were dragged through the streets. The incident effectively ended American interventionism in Africa for a generation.

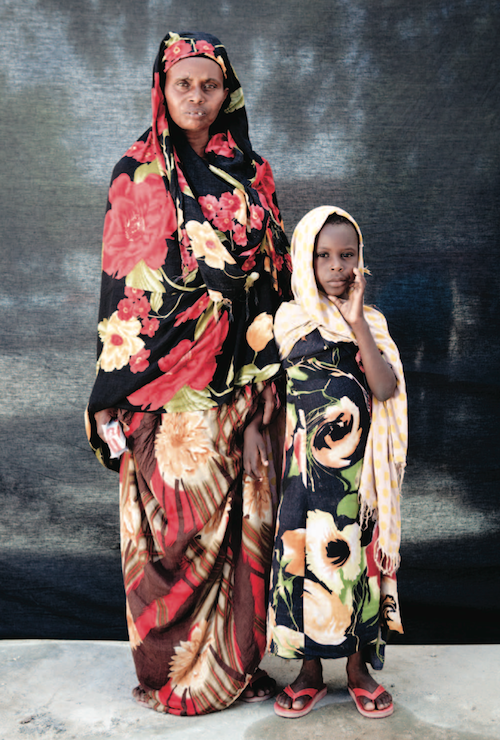

- IDP camps, like this one near the airport in Mogadishu, have sprung up all over Somalia’s capital city. The lack of aid available to them there has sparked a mass exodus of hundreds of thousands across the border into Kenya. Photo by Jason Florio

But then last year came the blossoming of the Arab Spring. Tunisian President Ben Ali and Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak were ousted amid mass protests, Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh narrowly escaped an assassination attempt (and soon agreed to step down), and Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi was facing a well-organized (and NATO-backed) insurgency that would soon lead to his violent death in the streets. Rightly or wrongly, I couldn’t shake the sense that the New York Times was suggesting that the time might be right for fresh intervention in Somalia. Times editor Bill Keller denied this, saying, “They sent us a harrowing story and vivid, arresting photographs. We put them before the attention of our readers. That’s our job.” But the Times has played a more complicated role than that over the last decade: from Judith Miller’s dodgy reporting in support of war in Iraq to Nicholas Kristof’s dew-eyed editorials on the democratic future of Egypt, the paper of record has often seemed only a hair’s breadth from the neo-conservative belief in spreading democracy through preemptive war, a policy that has given us a decade of global conflict and an international economic recession.

For an alternative view, I asked Tom Sleigh and Jason Florio to track the compass points of the Somali exodus from the aid stations of Mogadishu to the Dadaab Refugee Camp across the Kenyan border to the Eastleigh neighborhood of Nairobi. Tyler Stiem went to Somaliland (a democratic, breakaway region of Somalia in the north that Tristan McConnell and Narayan Mahon had covered for VQR two years before) to update our readers on the progress of self-rule there—and to delve deeper into the legacy of violent regime change. I asked, too, that Elliott D. Woods and Nadia Shira Cohen who had been in Cairo reporting for the VQR website in February and Anthony Ham who has traveled extensively in Libya over the last decade to look back on the revolutions of a year ago to consider both the American relationship to the strongmen who had ruled those countries and what challenges remain as those nations struggle toward better futures.

Their reports combine to create a mosaic portrait that is often grim. Millions in the Horn of Africa are not only facing drought and famine but also pervasive post-traumatic stress disorder, as an entire generation has come of age facing mass death. The efforts of aid groups, intent on trying to ease suffering and find a hopeful path forward, often score only minor victories. And the threats of al Shabaab in Somalia and of Salafists in Egypt and Libya are very real, and the swift rise of extremists already has some describing our moment as an Islamist Winter. Solutions, if there are any, will be hard to come by—in the Horn and throughout North Africa. It won’t be as easy as raking in the proceeds from a pop single or sending in troops to topple dictators. The writers and photographers in this issue portray a region far more complex than that, one on the brink of historic change but also wrestling with ancient crises. It’s not a simple view, but it demands our attention.