“History teaches that war begins when governments

believe the price of aggression is cheap.”

—Ronald Reagan

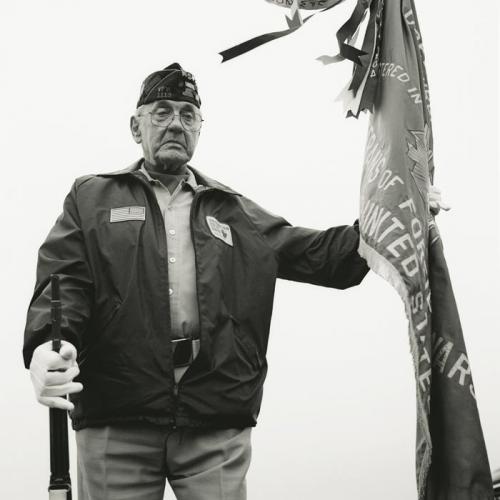

You can call it what you like—a timetable (Senator Barack Obama), a timeframe (Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki), a timeline (Iraqi Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari), a time horizon (President George W. Bush). Regardless, nearly everyone in the political sphere seems to agree that the United States will begin the withdrawal of its troops from Iraq in the next twelve to eighteen months. As we go to press, even Senator John McCain has begun to warm to the idea—though pundits have observed that McCain seems less personally swayed than politically aware that Americans have lost their stomach for the war, whether the surge is working or not. With consensus approaching and the prospect of an end in sight, the Iraq War has slipped from the headlines—overshadowed in stump speeches by the faltering economy, the high price of oil, and the reappearance of cultural wedges like gay marriage, abortion, and what defines a patriot. We, as a nation, seem to believe that, win or lose, the war is nearly finished, done with, history. Unfortunately, for hundreds of thousands of American veterans and their families, the war is anything but over.

According to the government’s own numbers, returning combat veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan are a third more likely to drink heavily or abuse drugs, two-thirds more likely to suffer from depression, and twice as likely to commit suicide than they were before deployment. A recent study by the RAND Corporation estimates that the number of combat veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan suffering from major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or some form of traumatic brain injury may top a half a million—nearly a third of all veterans of those wars. “There is a major health crisis facing those men and women who have served our nation in Iraq and Afghanistan,” said Terri Tanielian, the RAND study’s co-leader. “Unless they receive appropriate and effective care for these mental health conditions, there will be long-term consequences for them and for the nation. Unfortunately, we found there are many barriers preventing them from getting the high-quality treatment they need.”

Last year, Joshua Kors reported for the Nation on one of the most egregious examples of such barriers—the intentional misdiagnosis of PTSD as a preexisting “personality disorder,” in order to deny veterans their disability and medical benefits. More often, however, the poor mental healthcare for veterans has less to do with malicious misdiagnosis than with an under-funded Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), groaning under the burden of too many patients and too few healthcare professionals. An estimated 300,000 new cases of PTSD and major depression have been diagnosed among combat veterans in the last four years; during that same span, the VA has hired only 3,000 healthcare workers with expertise in treating those illnesses. The true scandal hidden in those numbers is the fact that Ira R. Katz, the VA’s Deputy Chief of Patient Care Services in the Office for Mental Health, estimates that proper mental healthcare through the VA system may reduce the likelihood of suicide by as much as 75 percent. Simply by allocating greater resources, Katz believes, our government could prevent the suicides of 400 combat veterans per month.

In this issue’s portfolio, we have gathered the stories of several Iraq War veterans and their ongoing—sometimes losing—battles with the memories of what they saw and did overseas. In Elliott Woods’s moving essay, Bill Rossin fights the guilt of not having been present when two members of his company—young men he had come to think of as sons—were killed by a suicide bomber. With the help of medication, Rossin no longer searches his home for IEDs at night, but he still has trouble sleeping and can’t hold a job. Wracked by paranoia, he has begun collecting guns. His story feels all the more ominous in light of Ashley Gilbertson’s searching profile of Noah Pierce, an Army specialist who shot himself near his Minnesota hometown after surviving two tours in Iraq. Through diary and notebook entries, letters, e-mails, and text messages, Gilbertson maps Pierce’s anguish as his psyche slowly unravels and he comes to regard suicide as his only option.

The Iraq War also represents the first major combat mission for American women. Laura Browder has gathered nearly fifty oral history interviews with women returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. For our pages, she has selected a half dozen of these interviews (and another half dozen for our website) to represent the range of stories she has collected—tales of combat and camaraderie, of sexual discrimination and determination, and of combat stress and depression. “In the end,” Browder writes in her introduction, “what struck me most about the women I interviewed was their capacity for survival—all the ways they balance their family lives and their lives in the military, the ways they found to keep going after seeing and experiencing horrific things.”

Joshua Casteel, as a student of religion turned Army interrogator at Abu Ghraib, wrestles with these demons as well. Though Casteel arrived after the systematic physical humiliation of prisoners that erupted in scandal, his mission remained the psychological dismantling of the detainees brought to his interrogation room. He found himself in the untenable position of being able to prove a person’s innocence only by pushing him emotionally past the point where any guilty person would confess. In the end, Casteel registered as a conscientious objector—but his conscience won’t rest; it circles back to the faces of the men he interrogated and the eyes of a child who came into his sights.

The portfolio concludes witha gathering of poems by Brian Turner, the first major poet to emerge from the Iraq War. Turner’s broad-ranging poems encompass combat and homecoming, the visceral terror of the moment and the weight of history, duty to comrades and abiding empathy for innocents caught in the crossfire. He reminds us of the power of language to transform trauma and the remarkable strength that comes from self-reflection. Turner speaks for more than a million and a half veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan who lack his command of language, but at the same time, it is hard not to feel that their silent guilt, heartbreak, and rage might find its own voice were it simply allowed an outlet.

In Ashley Gilbertson’s essay, Cheryl Softich, the mother of Noah Pierce, begs for a year’s mandatory counseling for all returning veterans. The plan would not be as simple as it sounds. It would require a considerable commitment of money, the hiring of thousands of qualified psychiatrists and psychologists, the establishment of a sizable bureaucracy within the already bureaucratic VA system to monitor the progress of hundreds of thousands of veterans. But what is the alternative? The RAND Corporation estimates that the loss to the economy—in productivity and corresponding buying power—could be billions of dollars. But, more importantly, what does it say about us as a nation, if we choose not to afford our veterans the best healthcare available? The supposed lesson of Vietnam was that, regardless of our side of the political aisle, we would commit support to our troops in combat. It’s time to honor that commitment.