Haiti swims in the American subconscious like a dream. Its history, we know, is related to ours, but that history is also an afterthought, preceded by images of earthquakes and dislocation. We remember that once upon a time Haiti was an American playground, much like Cuba, known for its resorts and tropical beauty. We know about its relationship to France, as well as its slave revolts and victories. Names like Toussaint Louverture, Papa Doc, Aristide, and Wyclef Jean roll off the tongue when Haiti springs to mind. But Haiti comes first as a dream of disaster: floods, deforestation, displacement, and disease.

Haiti swims in the American subconscious like a dream. Its history, we know, is related to ours, but that history is also an afterthought, preceded by images of earthquakes and dislocation. We remember that once upon a time Haiti was an American playground, much like Cuba, known for its resorts and tropical beauty. We know about its relationship to France, as well as its slave revolts and victories. Names like Toussaint Louverture, Papa Doc, Aristide, and Wyclef Jean roll off the tongue when Haiti springs to mind. But Haiti comes first as a dream of disaster: floods, deforestation, displacement, and disease.

It is through Edwidge Danticat that Haiti emerges beyond the illusion, and her fiction and nonfiction open our eyes to the history and complexity of the island. Her novel, The Farming of Bones, details the 1937 Trujillo massacre of Haitians in the Dominican Republic through the genocidal violence experienced in the life of one young woman. The Dew Breaker follows a former Tonton Macoute, known for torturing his victims when the dew was just freshly on the grass, living undercover with his wife and daughter in New York City. Her memoir, Brother, I’m Dying, describes her uncle’s emigration to America as a senior citizen and his subsequent death in a hospital, after being detained by American authorities, where his family was not allowed to visit him. In all her writing, Danticat bears witness without calling attention to herself. Exile, identity, memory, culture, and survival are all themes in her work.

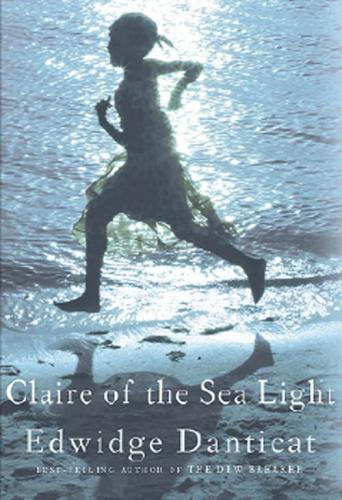

Those themes continue in her latest work, Claire of the Sea Light. The novel has its origins as a short story in Haiti Noir, a collection she edited for Akashic Books. Danticat has called it “a hybrid of a book, stories that are linked together, a kind of tapestry.” That is indeed what it is, with the events in Claire of the Sea Light taking place in the space of one day, woven together with many flashbacks to the past.

Death opens the story. It is May 2009, a year before the 2010 earthquake. A fisherman named Caleb is swept away by a freak wave. Claire’s father, Nozias, sees “a wall of water rise from the depths of the ocean, a giant blue-green tongue” that sweeps Caleb and his sloop away. Claire is at home, about to celebrate her seventh birthday. But even without Caleb’s accident, her birthday is already a day of death because her mother died giving birth to her. Every year, her father presents Claire with a new dress and a trip to the cemetery to visit her mother’s grave. Every year he also tries to give Claire away to a well-off, lonely woman, a fabric vendor named Gaëlle Lavaud. But this year Gaëlle finally agrees to this arrangement. She shows up to retrieve Claire wearing a white satin gown—she had hoped to entertain at home but was stood up—and then Claire disappears.

Birth and death are close sisters in Claire of the Sea Light. They come together like twins. “To most people, Claire Limyè Lanmè was a revenan, a child who had entered the world just as her mother was leaving it. And if these types of children are not closely watched, they can easily follow their mothers into the other world,” explains Danticat. Before dying in childbirth, Claire’s mother, also named Claire, worked in a funeral home, cleaning and preparing the dead. When she met her husband, Nozias, she smelled of the chemicals she worked with. “Whenever he told and retold the story of their meeting to his fishermen friends, he often added that he was the only man she liked who wasn’t dead.”

When his wife dies, Nozias brings his newborn to another woman, still breast-feeding her three-year-old. Gaëlle Lavaud was widowed herself, the day she gave birth—again the pattern of birth and death—when her husband was shot down outside the local radio station, Radio Zòrèy. Although Nozias thinks of Claire and Gaëlle’s daughter Rose as milk sisters, after nursing Claire once, Gaëlle refuses to do more. Nozias sends Claire to relatives until she is weaned at three and then brings her back to his shack by the sea, knowing he has little to give her. Meanwhile, Gaëlle loses Rose in an accident involving a drunken motorcycle driver when she is seven years old. Then Nozias begins asking Gaëlle Lavaud to take Claire as a restavèk, a servant.

Claire is one of many characters in the narrative, but she is the shining light—and she is the lynchpin—since everyone else is connected to her through Nozias or Gaëlle Lavaud. Through her narrative, Danticat shows the interconnectedness of everyone on the island, particularly with the children, women, and men in Ville Rose, a town next to the Caribbean Sea. In Ville Rose there is a mountain, believed to be haunted by the slaves who escaped to live there long ago, called Mòn Initil (Useless Mountain), and there is a castle, called Abitasyon Pauline, built when Haiti was still a French colony, a gift to Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister, Pauline. Anthère Hill is full of mansions where the wealthy live, with the slums of Cité Pendue a mere eight miles away. Danticat said she based the setting on the town of her parents, Cité Napoléon in Léogâne.

“Ville Rose was home to about eleven thousand people, five percent of them wealthy or comfortable,” she writes. “The rest were poor, some dirt-poor… . Twenty miles south of the capital and crammed between a stretch of the most unpredictable waters of the Caribbean Sea and an eroded Haitian mountain range, the town had a flower-shaped perimeter that, from the mountains, looked like the unfurling petals of a massive tropical rose, so the major road connecting the town to the sea became the stem and was called Avenue Pied Rose or Stem Rose Avenue, with its many alleys and capillaries being called épines, or thorns.” Flowers are represented in so many of the female characters depicted: Rose, Jessamine, Flore.

While natural beauty is all over this narrative—in terms of the sea, the vegetation, even in the caresses between lovers—atrophy is rampant as well. Danticat uses physical disability as a metaphor for a crippled nation: The dead fisherman’s widow, Josephine, has elephantiasis, dragging her leg behind her as she walks; the mayor (who is also the undertaker) has uncontrollable shaking in his hands and cataracts over his eyes; and a gang member has a prosthetic arm, a radio newswriter has asthma, and a restaurant owner has a facial tic.

Danticat’s prose is languid, imagistic, and metaphorical, but her tone shifts toward the center of the narrative. Here the action moves to Cité Pendue, the slum outside Ville Rose. Her tone is less lyrical as she describes an urban setting dominated by the street gang Baz Benin. “The men of Baz Benin gave themselves the monikers of Nubian royalty, which also happened to suggest menacing acts in Creole—Piye, for example, meaning ‘to pillage,’ Tiye, meaning ‘to kill.’ ” A young man named Bernard Dorien is friends with Tiye, the leader of Baz Benin. Bernard lives with his parents, who run a restaurant called Bè, Bernard’s nickname, which means “butter.” Further, she notes, “Watching these boys drift from being mere sellers to casual users of what they liked to call the poud blan, the white man’s powder, watching these boys grow unrecognizable to anyone but one another, Bernard’s parents were repulsed and afraid. But they still kept the place open, because the same blight that was destroying Cité Pendue was allowing them to prosper.”

Bernard went to school at École Ardin, the same school Claire attends as a scholarship student. When he isn’t helping out with his parents’ restaurant, he works as a part-time newswriter for Radio Zòrèy, the only radio station in Ville Rose. He dreams of hosting his own radio program, devoted to exposing the culture of the gangs.

Radio Zòrèy plays a pivotal force in the narrative. It is where Gaëlle Lavaud’s husband was murdered in the first half of the book, shot down by four men with M16’s. Moreover, it stands for the power of mass media in Haiti, where televisions are too expensive and much of the population is illiterate.

Louise George is a talk show host at the station. Her program is called Di Mwen—Creole for “tell me”—which centers on life-changing moments, particularly stories told by inhabitants of Ville Rose and Cité Pendue. Her riveting interview with Flore Voltaire, a maid in the schoolmaster’s household, is one of the highlights of the book. Flore was raped by Max Ardin Jr., the overweight son of the schoolmaster. And Flore has a son as a result: Pamaxime—“ ‘Pa’ a Creole prefix meaning both ‘his’ and ‘not his,’ the child’s first name could either mean ‘Maxime’s’ or ‘Not Maxime’s.’ Only the mother could know for sure.” The schoolmaster, Max Ardin Sr., has been Louise George’s lover. He often told Louise that “she was like a starfish … she constantly needed to have a piece of her break off and walk away in order for her to become something new. Of course this was always truer of him than her.” He also humiliated her professionally, but she metes out revenge as she tapes her radio program, exposing his son as a rapist and negligent father.

Danticat is known for her portraits of women, subjugated in the course of history. She also plays with images of Armageddon throughout Claire of the Sea Light, rendered even more poignant because these are the months preceding the earthquake of 2010. The plagues of Egypt are alluded to: Frogs don’t rain down but they do explode, thanks to the horrific heat. Parents lose their firstborn children to car accidents and professional assassins. Fish die—not because the sea has turned to blood but because it is so polluted, thanks to deforestation and silt. A terrific hailstorm occurs during the rape of Flore Voltaire. Insects don’t invade, but a spider blooms in the form of a birthmark on Louise George’s belly.

Yet beauty is also at play. Nozias remembers when Claire’s mother, early in her pregnancy, went for a night swim. She swam into a school of silver fish illuminating the black sea and then insisted their child be called Limyè Lanmè—meaning “sea light.”

Consequently, illumination is also a repeated motif throughout the book—the glow of kerosene lights inside the lighthouse gallery, the lights of houses on Anthère Hill, the beam of a flashlight outside a bedroom, the sheen of a white satin gown in the moonlight.

Finally Max Ardin Jr. goes to the sea where so much has happened in one day. He hears the search party looking for Claire. Bakers, net weavers, and boat builders are all calling her name. “The name was as buoyant as it sounded. It was the kind of name that you said with love, that you whispered in your woman’s ears the night before your child was born. It was the kind of name you could easily carry in your dreams, in your mouth, the kind of name that made you clasp your hands against your chest when you heard it being shouted out of so many mouths. It was the kind of name you might find in poems or love letters or songs. It was a love name and not a revenge name. It was the kind of name that you could call out with hope. It was the kind of name that had the power to make the sun rise.”

Claire of the Sea Light pierces the darkness. It supplies so many points of light.