On the roof of the Parvanta family’s sole remaining property in Kabul, clumps of grass have sprouted amid the orderly stands of rebar meant to support the pillars of floors that were never constructed. Assad Parvanta spreads his arms to encompass the scene.

“Look at this monstrosity,” he groans.

Garbage and wild bushes carpet the floor of an acre-sized pit to our left. Directly in front of us, the Bakhtawar Palace stands in all its gaudy glory: a charmless eighteen story high-rise slated for residential and commercial use, built on the parcel where Assad’s family home once stood. Assad sold the property in 2003, a year or so after American bombers chased the Taliban from Kabul. A plastic banner suspended from the Bakhtawar’s upper reaches bears the phrase Ma’sha Allah—”As God has willed.” Six million dollars of capital from the Onyx Group and the Azizi Bank may have greased the skids, but the Bakhtawar Palace, the developers boast, is a manifestation of the Almighty. To me, it looks more like a metaphor for the entire American effort in Afghanistan: eighteen slipshod stories constructed with criminal money, on a faulty foundation designed for twelve, in a neighborhood zoned for three, in a country on the verge of collapse.

Assad tells me he’s known three expat project managers who have quit the job over the years because the owners refuse to heed their safety warnings. “There’s no insurance for any of the tenants,” he explains. “If there’s a fire, heaven forbid an earthquake, they’ll have no protection. It’s a disaster waiting to happen.”

Onyx Group’s website shows a mockup photo of the building surrounded by luxuriant grass and palm trees, more South Beach than Shar-e-Now. “Each unit will boast of the highest quality of materials available in accordance to its intention of being an architectural gem in Kabul’s evolving cityscape.” Afghanistan is famous for its gems, but the Bakhtawar isn’t one of them. Kabul will never look like that picture, nor match up with Washington’s erstwhile fantasies of a stable and democratic Afghanistan. The reality is in the faulty foundation on which the whole thing stands.

Thirty-three years ago, on the plot where the Bakhtawar Palace now stands, the Parvanta family lived in their modest home, designed with love by Assad’s father, Akram. “If you can, just try to imagine one of those beautiful old-style houses here, surrounded by a garden,” Assad says. Mohammad Akram Parvanta spent his youth in Germany, sponsored by the Afghan reformer King Amanullah, who hoped to nurture the seeds of an educated elite that would shepherd his realm into the modern age. Akram returned to Afghanistan after two decades abroad with an advanced degree in engineering and a distinguished career ahead of him. He was chief architect on the Mahi Par Gorge project, among Afghanistan’s first technological accomplishments. Later, he served as ambassador to Indonesia and Poland, rounding out his working life as a minister in the government of Zahir Shah. Akram’s home was awash with visitors, who would come for tea under the grape trellises and towering cypresses that shielded his garden from the summer sun. There were apple trees too, and rose bushes—Akram’s dearest possessions, which he painstakingly pruned and hybridized himself.

Assad remembers how, as a boy, he woke for school and gazed out picture windows toward the Paghman Mountains to the west. Back then, the Paghmans were capped in snow yearround, looming almost close enough to touch. From the roof today, a stifling July afternoon, we can barely make out the silhouettes of the peaks through the khaki smog blanketing the valley. Even in silhouette, it’s obvious the snows are gone.

Assad’s family has gone, too. In 1979, Assad and the elder of his two sisters, Fruzan, fled to the United States in the turmoil of Communist coups that eventually resulted in the Soviet invasion. A year later, his mother followed with his sister Farrukh. His mother intended to escort Farrukh to Maine, then return to Kabul, but her children took her passport and forced her to stay. Almost nothing remains of the Shar-e-Now they knew, a place filled with familiar faces and simple, elegant homes.

“You can’t imagine the beautiful people of Kabul,” Assad says. “You couldn’t walk down one block without seeing twenty people you knew. You’d have to duck your head and just wave and keep walking or you’d never get anywhere.”

Foreigners lived in the neighborhood without worrying about security, and his mother and father were friendly with them. There was no razor wire. There were no blast walls, because there were no suicide bombers. In a black and white photo Assad shows me from 1963, he’s wearing lederhosen, a gift from a German family who lived across the street. His sisters stand by his side, dressed in plaid jumpers and Mary Janes. Bobbed hair, smiles.

Today, Assad wears a long tunic and baggy trousers. Out of growing concerns about his safety, he stopped wearing Western clothes on the street a year ago, hoping to attract less attention. “I never dressed like this in my life,” he grimaces. “Now look at me.”

Assad studied at the prestigious French high school, the Lycée Esteqlal, where Ahmed Shah Massoud and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar—who would later become ferocious mujahedin commanders— graduated only a few years ahead of him. On a trip to Lahore with the Afghan national basketball team, Assad was horrified by the squalor of the Pakistani slums. “When I got back to Kabul I wanted to get down on my hands and knees and kiss the ground. ‘Thank God,’ I said, ‘I’m back to civilization!’”

All of Shar-e-Now’s streets were paved, and a city decree bound property owners to keep their sidewalks clean. Proprietors also respected the neighborhood ordinance limiting buildings to three stories, so there was no skyline to block the view of the grandiose mountains. There were nightclubs, movie theaters, and a bowling alley. You could go on a date with a girl, maybe even hold her hand. There were almost no burqas. At least not in posh quarters like Shar-e-Now.

Assad points to the corner where he used to hang out with his friends on Thursday nights, checking out girls. For maybe the fourth time, he asks, “Can you imagine it?”

Assad’s memories are colored by nostalgia, and the Parvantas were a wealthy and important family that enjoyed the best of what the city had to offer. In the 1970s, Kabul was, as now, among the poorest cities in the world, all but untouched by development, plagued by near-universal illiteracy and soaring infant mortality rates. But whatever problems Kabul had back then have been amplified by three decades of war and a population explosion. Kabul is among the fastest growing cities in the world, and four million people live now where there were fewer than a million during Assad’s childhood.

Most of Kabul’s new arrivals are impoverished villagers whose families have poured in from the countryside to escape near-constant conflict. They produce children at a blistering rate: 38 births per 1,000 people annually, triple the fertility rate of the United States. Kabul’s infrastructure has never grown to accommodate the pulsing throngs. Mud-brick slums fill every nook and cranny of the periphery, clinging to impossible outcroppings on the rocky hills. Gangs of children traipse down the slopes to fetch water in the morning. The lucky ones go to school after they’re done, but many go to work.

Their fathers loiter by the thousands at traffic circles throughout the city, hoping for day labor on a construction site. As for their mothers, it’s better not to ask. Save the Children rates Afghanistan the worst place in the world to be a mother; 86 percent of women give birth without medical assistance, and one out of eleven dies in pregnancy or childbirth. Not to mention, women here exist in a cultural sphere where they are little more than slaves, married

off as children and afforded virtually no legal protection, despite the fact that new laws exist to protect them.

Kabul today gives the impression of a throbbing mass ready to burst. But it wasn’t always this way. Not so long ago, young Kabulis like Assad believed things were on the way up. He never could have predicted the agonizing birth pangs his country would endure on the road to modernity. Nor could he have guessed how horribly disfigured the new Afghanistan would be.

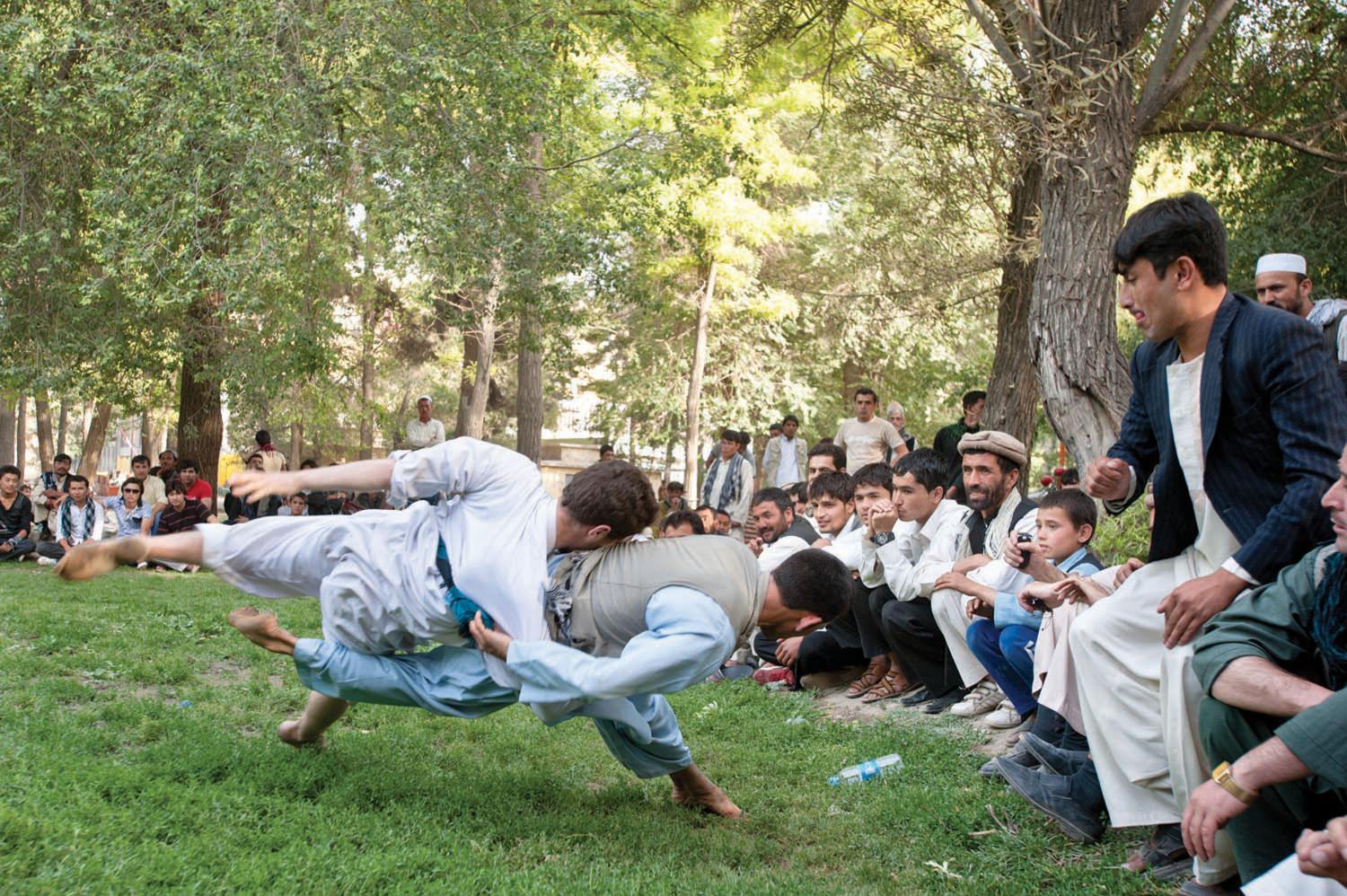

Looking out over Shar-e-Now Park, trying to envision the chic Kabul that Assad describes, I picture a group of almond-eyed girls sauntering down the sidewalk in skirts, their slender legs catching the last golden rays of the sun. Young Assad, leaning against the park’s fence in jeans and a t-shirt shirt, a buddy on either side, turns his head to watch them pass. I imagine the grinding sounds of the street replaced by birdsong, and the acrid air cleansed and suffused with the perfume of roses and cypress.

“Yes, I can imagine it,” I tell him.

But he’s still staring out at the park, lost in a city that’s gone forever.

In April 1978, Afghan Communists murdered President Daud and installed Noor Mohammad Taraki at the head of the fledgling Communist government. Taraki launched a reign of terror against figures associated with previous regimes. He also unleashed his secret police on the rival faction within the Communist party itself, known as the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA).

Taraki was head of Khalq faction, mainly comprised of non-elite Pashtun nationalists who advocated a forced march toward socialism, whatever the cost. Immediate and uncompromising “reforms” followed the coup. Parchamists, mostly urban intellectuals—the Khalqists’ bitter enemies—favored a slower road to a socialist state, knowing full well that Afghanistan lacked the education levels and industrial proletariat that were preconditions for a Marxist revolution. At the grassroots, though, the differences between Khalqists and Parchamists were obscure, as likely to be a matter of personal associations as ideological convictions. The factions quickly morphed into modern manifestations of the tribe, the entity that had always dictated Afghanistan’s internal affairs.

Taraki imposed a ten o’clock curfew, but few Kabulis waited that long to go home. “The streets were empty by dark,” Assad recalls. “If you saw headlights, you knew it was a government patrol or secret police going to pick someone up.”

A year after Taraki’s coup, at about nine o’clock on an October night in 1978, a knock came at the Parvantas’ door. Assad, eighteen at the time, hopped out of bed and told his mother he’d answer it. A few days before, a cousin had come seeking Akram’s advice about a family issue. Akram was the family headman, and cousins were always dropping by with petty problems.

Instead, Assad opened the door to find two twenty-somethings in overcoats.

“Is Akram Jan home?” one of the men asked.

“Jan” is an informal term of endearment in Dari, reserved for friends. “I’d never heard anyone except my father’s closest friends refer to him as Akram Jan,” Assad says. “This was a minister, a very important man. People called him wazir or safir sahib. Strangers didn’t call him ‘Jan.’”

“Akram lives at the end of the next block,” he told them, thinking they might be looking for a younger, less important Akram who lived down the street.

“No,” the man who’d spoken before replied. “We’re from the Ministry of Interior. We’re looking for Akram Jan Parvanta.”

The man pulled his coat aside, revealing a pistol. More men emerged from the shadows beside the doorway, dressed in military uniforms, carrying assault rifles. They brushed past Assad and into the house, where they found Akram eating in the family library.

“They told him he could finish his dinner,” Assad remembers, “but, of course, he’d lost his appetite.” He remembers one of the henchmen muttering, “He looks so old and frail.” Akram was seventy, but still upright and dignified. The men ordered Akram to change his clothes, and one of them followed him upstairs to his bedroom. They told Assad to get changed too.

Assad’s mother pleaded frantically with the men not to take her husband and son. “He’ll only be gone for an hour or so,” the men reassured her. “They were very polite,” Assad remembers.

When Akram came back downstairs, the men led him to the door. They started to take Assad out too, but then one stopped. “He looked at my baby face and said, ‘He’s young, let him stay here with his mother.’ Wherever that man is today—if he’s alive, I wish him the best; if he’s dead, may he rest in peace. I have no doubt that man saved my life.”

Through a crack in the courtyard gate, Assad watched as the men escorted Akram to a Volga sedan parked in the darkened street. They opened the door and Akram obediently ducked into the back seat. He wasn’t alone. In the dome light, Assad made out the faces of his uncle, Sherif, and a young cousin named Hazratullah. More cars idled around the corner with their headlights off. Armed men stood watch in the shadows.

The Ministry of Interior agents closed the door behind Akram, then they got into the front seat. The Volga slipped off into the night.

“And that was it,” Assad sighs.

Taraki’s death grip on Kabul lasted a year and a half before he too was murdered— smothered in his bed, wrapped in a blanket, and buried secretly. The assassination order came from Taraki’s prime minister and fellow Khalqist, Hafizullah Amin. By September 1979, when Amin assumed the highest offices of the PDPA and control of the Afghan government, the country was on the brink of implosion. In March, thousands had been killed when the Afghan army put down massive anti-Communist riots in the western city of Herat, close to the Iranian border. Amin warned his Soviet patrons that the country would be engulfed in chaos if they failed to intervene.

Amin’s enemies were legion: party rivals, intellectuals, and a growing number of anti- Communists, not least the prominent religious figures and their followers who would form the anti-Soviet mujahedin in years to come. In fact, the mujahedin did not wait for the Russians: a jihad against the Afghan government was already in full swing by the time they arrived.

By December 1979, the brutality of Taraki and Amin had irreversibly contaminated the image of the Afghan Communist party. Together, the two were responsible for a minimum of 27,000 political executions. Some historians place the figure as high as 50,000. The majority of victims were lined up and shot beside mass graves at Pul-e-Charkhi Prison. When Soviet advisers urged Amin to staunch the blood flow and take measures to rehabilitate his government’s image, he rebuffed them. “Comrade Stalin showed us how to build socialism in a backward country,” he insisted. “It’s painful to begin with, but afterwards everything turns out just fine.”

Akram Parvanta and his brother Sherif were among the dead, but the government made no effort to inform the family. In late 1979, less than three months after taking office, Amin belatedly realized he needed to wash the blood from his hands if he was to have any hope of hanging on. He released a list of 18,000 people he claimed had been killed by Taraki, though in reality his men had done more than their share. Assad went with his mother to the Ministry of Interior. They pored over the roll a dozen times, but the Parvanta brothers’ names weren’t there.

They never found out how Akram and Sherif died. They had relatives in the government and police, even in the secret police, but no one talked. “Once you went into that Ministry of Interior system,” Assad shrugs, “you never came out.” Even your name could disappear.

The Parvantas weren’t unique. Classmates and neighbors lost their fathers and uncles too. Few prominent families survived the pre-Soviet Communist period without at least one fateful knock. The closest thing to closure the Parvantas ever had was a rumor by way of a family friend who miraculously survived detention at Pul-e- Charkhi, and who told them he’d seen Akram and Sherif thrown into a cell late one night for a few hours, then taken away again. Odds are the elderly brothers were shot unceremoniously that same evening, then dumped in an unmarked hole.

Whatever happened to Akram and Sherif, the Parvanta name was marked. Assad studied hard and was sure he’d done well on his university entrance exams in the autumn of 1978, but when the Kabul University placement rosters came out that summer, he couldn’t find his name among the accepted class at the Faculty of Engineering, the choice destination for top students. He was heartbroken, and he sank further into despair when a cousin called to tell him that she’d found his name on the roster for the Teachers Training Institute, where only the bottom of the barrel wound up.

“I wouldn’t have been caught dead there,” he says. “And they knew that. This was a clear signal that I was unwanted at the university.”

Assad sulked at home for months while the government’s murder machine kept grinding away. All-out civil war began to seem inevitable. The Soviet Union had gradually, begrudgingly, increased military aid to Amin, and it looked more and more like they might step in to prevent the collapse of the state.

Assad’s mother was at the end of her rope. “My mother was the most beautiful woman,” he remembers. “I never noticed gray streaks in her hair until after my father disappeared.” Mrs. Parvanta knew what the future had in store for her son, a branded young man in a country where name and family reputation are more valuable than life itself. She also worried her son might be conscripted to fight for the government that abducted her husband, and so she bribed an official with the equivalent of $2,000 to get passports for Assad and his twenty-four year-old sister Fruzan. They got lucky in a meeting with the American consul, who was sufficiently impressed with their English to grant them visas to the United States.

Suddenly, on October 25, 1979, Assad and Fruzan were saying goodbye to their mother in the courtyard of their Shar-e-Now home. Assad caved in and wept, terrified by the uncertainties ahead and crushed at the thought of leaving his father’s home and his mother behind. He knew he wouldn’t be coming back—at least not any time soon.

As the car idled in the street, waiting to take them to the airport, Assad’s mother grabbed him by the shoulders. “Listen to me,” she said, unshaken. “Are you a boy or a man? Go now, and take care of your sister.”

The Soviets watched without enthusiasm as the wheels spun off Amin’s government. They gradually ramped up funding and materiel support to the Communists but balked at Amin’s requests for Soviet combat troops to protect his regime from the growing opposition. Soviet bureaucrats rightly believed that the Afghan government was Communist in name only—hostile, illegitimate, or simply irrelevant to most Afghans.

With more advisers and weapons on the way to Kabul every day, a Foreign Ministry official named Anatoli Adamishin penned an excoriating memo to his superiors: “To hell with Afghanistan. Why on earth should we get mixed up in a completely lost situation? We are wasting our moral capital,” he wrote. “If they are incapable of running their own country, then we will not succeed in teaching them anything.” Adamishin admonished Moscow to avoid making the Soviet army a party in a civil war that could only end badly.

Soviet officials at the highest level shared Adamishin’s skepticism. When Taraki had requested troops to put down the Herat uprising in March 1979, Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin warned him, “If we sent in our troops, the situation in your country would not improve. On the contrary, it would get worse. Our troops would have to struggle not only with an external aggressor, but with a part of your own people. And people do not forgive that kind of thing.”

From the other side, the Soviet Union’s powerful military and KGB urged Moscow to action by inflaming paranoia about how the Americans might be conspiring to profit from instability on the USSR’s southern flank. Their case was buttressed by accusations that Amin had been recruited as a CIA agent while pursuing postgraduate study at Columbia University in New York. Amin admitted that the CIA had made overtures, but he swore he’d never worked for them. The Soviets were never fully convinced.

Amin’s prognosis was terminal: he controlled less than 20 percent of the countryside, where agricultural collectivization and education reforms, particularly those related to women, stirred bitter resistance among deeply conservative villagers and their mullahs. Members of his own faction and rival Parchamists were tearing each other apart with insatiable bloodlust. Officers were defecting from the Afghan army to the resistance, and the proto-mujahedin were already well entrenched in Pakistan, where they received weapons and funds from an Islamist government keen to deal a blow to Communism.

If the Afghan Communists fell, the Soviets worried, who might fill the void? Disaster scenarios infected the Soviet decision-making process. A Communist defeat in Afghanistan could embolden opposition movements in the USSR’s Central Asian Republics, where socialism had been brutally imposed and barely held sway over rural Muslim populations that shared many of Afghanistan’s cultural attributes. Like the Americans in Indo-China, the Soviets fell under the spell of domino theory; unlike the United States in the 1960s, however, the Soviet Union in the late 1970s was already in deep decline, with its economy on the brink of failure and Moscow’s influence at home and abroad rapidly waning.

In hindsight, concerns about the potential impact of instability in the south were overblown, especially in comparison to the more perilous domestic issues that would eventually undo the Soviet Union. But at the time, Afghanistan’s predicament seemed to threaten the empire at its core—and in December 1979, the Soviets finally swung into action.

Amin had always assumed that the Soviets would send in the necessary forces to protect him once his situation reached the boiling point, but he was fatally misled. The Soviets knew that Amin’s reputation was irredeemable, and that, as long as he was at the helm, the Communists could never rule effectively. Ever since Taraki’s murder, the Soviets had merely been stringing Amin along while they mulled over ways to wipe the slate clean.

Moscow flew Soviet special forces units to Bagram airfield and put them up in safe houses in Kabul. On the evening of December 27, 1979, special forces, dressed in Afghan uniforms, moved to the Taj Bek Palace on the western fringe of the city. They waited for the signal—two rocket flares—then stormed the palace gates alongside a full battalion of Afghan army soldiers. The assault wasn’t as quick and dirty as they would have liked; in the forty-five minutes it took to seize the palace, five Afghan troops and five Soviets died. No one bothered to tally the dead in the palace ruins, but soldiers who were there estimate as many as two hundred palace guards were killed. Amin went down in a hail of bullets beside his five-year-old son, also shot to death.

While the palace siege was underway, Soviet troops and their Afghan counterparts seized critical communications equipment and strategic ground throughout the capital. There was no turning back now. The Soviet adventure in Afghanistan had finally begun.

Amin had lasted just 104 days in office, but the Soviets would go on to fight in Afghanistan for nine years and forty days, at a cost of more than 15,000 troops and between 600,000 and 1.5 million Afghans. They would prop up two successive Communist leaders—Babrak Karmal and Mohammad Najibullah, both Parchamists— but in the final equation, they were no more successful in stabilizing Communist rule in Afghanistan than Amin or Taraki had been.

When the Soviet 40th Army withdrew across the Amu Darya in February 1989, the officers and men knew they were leaving a country in the throes of self-destruction. They weren’t as jubilant as one might expect, and there was little gloating. Whatever happened in Afghanistan, it certainly was not a victory.

Some of the men sang the soldier ballads that had become famous over the years; some of them wept. And as they turned their tanks and armored personnel carriers toward a home front that was itself on the edge of collapse, only the senior officers and civilians who’d dedicated a decade of their lives to the Afghan war could anticipate how bad it would get. Few of the others could be expected to care.

Assad Parvanta had almost twice as many credits as he needed when he graduated with a degree in International Business from the University of Colorado at the age of twenty-nine. He’d had a difficult time finding his niche, so he tried a little of everything, but international commerce seemed like a good fit, and soon after graduation he landed a job at a shipping company called Emery Worldwide. It was 1989, the year of the Soviet pullout. Some of his friends in the refugee community celebrated the withdrawal and made elaborate plans to go home. Assad was less sanguine. “When the US refused to recognize Najib’s government, I knew it was hopeless.”

He feared the mujahedin would turn the guns on themselves, and he was right: an impenetrably dark chapter in the war was just beginning. In the ensuing years, while Assad got married, started a family, and climbed the corporate ladder, Afghanistan plunged into nightmarish internal strife. Najibullah continued using the Afghan air force to bomb the valleys into submission, but he ran out of fuel when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. The new Russian government cut his funding entirely, and now the violence that had plagued the countryside engulfed the cities too.

Tens of thousands of Afghan civilians died as Ahmed Shah Massoud, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, Abdurrashid Dostum, and Abdul Ali Mazari, among others, rained rockets and shells down upon each other’s positions from the hills above Kabul. Mujahedin militiamen raped and mutilated women belonging to adversarial ethnic groups. They preyed upon the Hazaras, a Shia minority prominent in west Kabul, with special zeal. Local legend has it that men loyal to Hazara commander Abdul Ali Mazari visited punishment in kind upon anyone who strayed onto their turf, carving off women’s breasts and sending them home bleeding to their families.

News about the conflagration in Kabul trickled out of the country in bits and pieces. Under the Soviets, most information that escaped the Afghan void was propaganda, and friends who remained in Kabul were too afraid of the secret police to talk openly on the telephone. Now that the Soviets were gone, the mujahedin had so thoroughly destroyed the communications networks that there was no way to get information at all. The interim government of mujahedin leader Burhanuddin Rabbani, that arrested and replaced Najibullah in 1992, tottered on until the mid-1990s, though the government exercised no authority whatsoever in the provinces, which were entirely within the hands of warlords— some loyal to Kabul, some not.

Kabul and its allied warlords soon faced a new threat: a group of highly motivated, well-armed Islamic students and mullahs from the south, under the command of a one-eyed Kandahari cleric named Mullah Omar. The Taliban were not, for the most part, mujahedin veterans of the anti-Soviet jihad; their numbers were drawn primarily from madrassas in Pakistani refugee camps. Early on, they were uncorrupted by the decade of fighting and backstabbing that had contaminated the original mujahedin factions. They quickly won the support of Kandaharis by violently opposing highway bandits and replacing warlordism with Sharia governance. As their reputation spread and their power grew, they moved north from Kandahar, killing and co-opting warlords along the way.

By 1994, the Taliban were at the gates of Kabul, and by 1996 they controlled almost the entire country. They brought a welcome level of security and stability, but they enforced their skewed religious agenda ruthlessly. Men were forced to grow beards and wear turbans, and no one dared complain when girls were banned from going to school. Religious police beat men caught outside the mosque at prayer time; singing birds, card games, and sports were forbidden. Public punishments based on Hammurabi’s Code were about the only form of public entertainment, including the stoning of men and women accused of adultery and amputation of thieves’ hands. To mark their triumphant entry into Kabul, the Taliban took former president Najibullah from house arrest, castrated him, then dragged him to death behind a truck. They put his body on public display as a warning.

Assad was living in Dubai when the Taliban began their northward march, working as Middle East director for a California-based logistics company called Fritz Companies. He was the proud father of a baby girl, whom he and his wife named Ariane, an ancient name for Afghanistan. Their second child, a son, whom they named Elias, was born in 1997, a year after the Taliban solidified their control. A few intrepid journalists made their way into Talibancontrolled Afghanistan, and Assad was horrified by their reports. The American photographer Steve McCurry had been traveling to Afghanistan throughout the mujahedin civil war and the battles with the Taliban; his photos showed a Kabul that looked as if it had been struck by an atomic bomb.

“By that point,” Assad tells me, “I think I was so exhausted that I didn’t even care.”

But he did care. Whenever he would go home to visit family in the States, the old arguments would erupt over dinner: how it could have been different, what the world might do now to fix it. As the nights wore on, passion and nostalgia gave way to emotional, sometimes volatile debates. “Never, in all those discussions, did anyone ever mention the possibility of American troops on the ground in Afghanistan,” Assad recalls. “It would have been beyond our wildest dreams, so impossible that no one even thought about it.”

In 1999, after seven years in Dubai, Assad resigned from Fritz and came home to Denver with his wife and kids. He bought a home, did consulting work for e-commerce startups, watched his stock market nest egg grow. For a refugee kid from Kabul, he was well on his way to achieving the American dream. And then, 9/11.

Al Qaeda had their base of operations in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, and the US moved swiftly toward retributive action in the Hindu Kush. By October, US Special Forces were fighting their way across Afghanistan, escorting a hitherto unknown Pashtun exile named Hamid Karzai to Kabul. They were joined by the Northern Alliance, a coalition of former anti-Soviet mujahedin-cum-warlord militias who’d been routed by the Taliban in 1996 and were eager to exact their revenge with the added muscle of American bombers and special operators. By December, Al Qaeda’s training camps in Afghanistan were empty, senior Taliban had fled to Pakistan, and the rank and file of the Taliban government and security forces had melted back into the rural landscape from whence they came.

This time, it was Assad who was giddy with the possibilities. He still held the deeds for his family’s properties in Shar-e-Now, and he lay awake at night dreaming of returning to Kabul to settle his family’s unfinished business. At first, he thought he would just sell the properties so that he and his siblings could finally put the past to rest. But, in early 2002, he learned that the interim Afghan government was issuing visas, and Afghan exiles were beginning to return. Assad was self-employed, and he thought, “The world is in there now. If you don’t do it now, you’ll never do it.” By March he was soaring over the Reg Desert on an Ariana flight bound for Kabul.

What he found in Kabul shocked him. The city was utterly destroyed; there was no electricity, no running water, and very little food. “The people were like zombies,” he remembers. The Intercontinental Hotel was the only formal establishment open for business, and they were charging $200 a night to sleep in the corridor. Assad connected with a man who used to work for his family, whom he calls Hajji, who agreed to work as his driver. Hajji also allowed Assad to stay at his home with his wife and children. There was simply nowhere else to go.

Shar-e-Now had been spared the brunt of the mujahedin war’s destruction, and Assad was relieved to find his family’s home and the adjacent two-story commercial building intact. No one remained from the old neighborhood. He went around to a dozen houses where he used to have friends and didn’t recognize a soul. The new residents were cold, sometimes hostile. They were squatters living under dubious arrangements in the houses of refugees who they had assumed would never come home.

Assad’s sense of anonymity in the neighborhood of his youth was the least of his concerns. When he entered the commercial building his father had started constructing, but never finished— the one with the rebar and weeds on the roof, beside which the Bakhtawar now looms— burly thugs with Kalashnikovs stopped him in his tracks. “Who the hell are you?” they wanted to know.

“Who the hell are you?” Assad shot back, indignant.

Unbeknownst to the Parvantas, a cousin who’d stayed behind—through all the years of the Soviet occupation, mujahedin fighting, and Taliban government—had installed himself as custodian of their properties, and he’d leased them out, without any authority, under an informal arrangement called sar-quflee.

Under sar-quflee, a tenant pays a landowner a lump sum to rent a property indefinitely. When the landowner repays the sum, he can begin charging the tenant monthly rent, or kick him out. So long as the original amount remains unpaid, the tenant has full rights to the property. “It’s sort of like pawning your property,” Assad explains.

The cousin, Hazratullah, was the same one who’d been taken with Akram and Sherif on that March night in 1979. He had mysteriously come back alive from his detention, and his survival cast a pall of suspicion over him. “He’d always been the family black sheep, a real wheeler and dealer,” Assad says.

Assad looked down the hallway and saw guns strewn all over the place. The thugs with the AK-47s escorted him to an office, where an unfriendly mujahid—clearly the boss—demanded to know what he wanted. “I’m Assad Parvanta,” he said. “I own this building.” With his bodyguards looking on, the man (Assad told me not to identify him, but I can tell you that he’s the brother of a Panjshiri mujahedin commander who is now in the uppermost echelon of the Karzai government) told Assad that Hazratullah had made a sar-quflee arrangement with him for a large sum, and that if he had a problem, he should take it up with Hazratullah.

Assad was livid. “Who the fuck is Hazratullah to do this?” he shouted, but the man just shrugged him off, and his henchmen escorted Assad to the door.

“At first I was just going to find a buyer and sell,” Assad said, “but this guy really pissed me off, and that’s when I became obsessed.”

Assad fumed all the way back to Denver, where he found a job offer from another logistics firm called UTi Worldwide waiting for him. He accepted, but the property dispute was a stone in his shoe, and after just two months he requested a leave of absence to go back to Kabul—this time with power of attorney from his mother and siblings. Assad’s boss gave him eight weeks.

Back in Kabul, Assad hired lawyers and prepared a legal case against the Panjshiri, based on the fact that Hazratullah had no authority to rent or sell the property. The Panjshiri stayed put and refused to pay rent, and Assad was often forced to deal with him in the staircase—sometimes that was as far as the bodyguards would allow him into the building.

“When I threatened to take him to court, it wounded his pride.” The Panjshiri told him, “I hear you have a lot of lawyers in the US and you pay them a lot of money to handle your problems, then you settle out of court. In Afghanistan, we spend our money buying off the judges, then we settle out of court.” It was a foreshadowing of things to come.

“A guy like that would rather pay $500,000 to bribe a judge than just pay the $50,000 he owes,” Assad says. “They’ll pay all that money just to be right.” Assad spent five months in Afghanistan on the second trip, during which time he sold the house his father built and the acre of land on which it sat. He went home with a heavy heart, and with his own pride smarting from the arrogance of the warlord squatter in his father’s building.

Nothing was the same back in Denver. Work became a daily slog that brought him no fulfillment. The quest to get his father’s property back hung over his every waking moment. His wife noticed a change; he was aloof, unable to sleep, constantly jabbering on and on about the property and what he could do with it if he could just get rid of that damned Panjshiri.

When he entered the commercial building his father had started constructing, but never finished, burly thugs with Kalashnikovs stopped him in his tracks. “Who the hell are you?” they wanted to know.

Rather than selling and getting out, Assad started to think of investing in the remaining property. If he could finish the last three stories on the commercial building, he could charge handsome rents to the international non-governmental organizations and foreign contracting companies who were moving into Kabul in droves to help with reconstruction and humanitarian relief. He could live off of the rents alone, and if the security situation stayed stable, maybe he could even bring his wife and kids to Kabul, at least to visit.

“My mother warned me,” he admits. “I wouldn’t listen. I told her, ‘The Americans are there; it’s different this time.’ She knew what would happen. If I’d just listened to her then I could have saved myself a lot of headaches.”

In March 2004, Assad asked UTi for another leave of absence.

Assad never went back to work. The Share- Now property dispute has fully taken over his life. In nine years, he estimates the project has cost him several million dollars in lost income and legal fees. His wife’s salary as a registered nurse and the modest income they receive from his investments keep the family afloat, but the strain has taken its toll. The dispute takes him away from his wife and kids for months at a time, and their patience wore thin long ago. Plus, he never seems to get anywhere.

The Kabul municipality refuses to grant him the permit he needs to finish the construction of his father’s building. They’re still clinging to the ordinance from Assad’s youth that limits buildings to three stories. Once, Assad seethed in the zoning commissioner’s office. “How can you tell me there’s a three-story limit when an eighteen-story building just went up behind my property?” Nonplussed, the official replied, “Those are mafia people behind that construction. If you have that kind of power, please, do whatever you want.”

Not until 2009 did Assad successfully evict the Panjshiri from his building. In that whole time, the Panjshiri never paid more than a thousand dollars a month for thirteen rooms of office space, and he only began paying that in 2005. On the first story of the building, Hazratullah had given sar-quflee to small shop owners, who claimed he owed them tens of thousands of dollars. No one would ever consider buying the property with so many hangers-on. In the end, he had to pay some of them off.

We stand in front of the building on our way out, on crumbling aquamarine sidewalk tiles, looking at his new tenants’ storefronts. They’re all paying rent now, legally, but Assad is unimpressed with their wares: garish pleather shoes on racks by the window and mannequins dressed in gaudy chiffon dresses. Metal grates protect the windows. There are thieves now. But at least they’re open for business, and they’re selling dresses, something unthinkable under the Taliban. You couldn’t even have mannequins with heads or faces under the Taliban. Some stores still scratch out their mannequins’ features, out of habit, or fear, or both.

A sweaty Hazara laborer mixes a heap of concrete a few feet away, right there on the sidewalk, and another gaggle of workers busily spreads a sand foundation for a new stretch of sidewalk in front of the building. There’s no end of construction in the city, no end to the banging and clashing of iron and concrete, the whine of saws and the spitting crackle of welding torches. There’s work now, even if it’s seasonal and doesn’t pay shit. Boys and girls are going to school here in the city, even in poor neighborhoods, and you can get almost anything at the bazaar. To some of these men, so accustomed to poverty and privation, it might seem as if Kabul is on the way up.

Of course, it’s all a mirage. Billions of dollars have poured into Afghanistan since 2001 from international donors—donor money accounts for four-fifths of the $14 billion GDP— but there is no native economy to show for it. Trucking, construction, and security businesses have flourished, gorging on the smorgasbord of lucrative and shoddily monitored contracts proffered by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the United States Department for International Aid. Scores of “poppy palaces” have risen from the rubble in the wealthy Wazir Akbar Khan and Shar-e-Now neighborhoods— heinous, Smarties-hued blocks with emeraldgreen reflective windows and razor-wired walls, guarded by men with machineguns. “If you think these are bad,” one of my friends says, “you should see what they’re building in Dubai.”

The side streets where the narchitecture is most prominent are almost without exception unpaved, pocked with potholes into which a small car might completely disappear, especially in the shoe-sucking mud of winter. It’s plain enough to see that billions in development money have made a handful of Afghans filthy rich, but have done virtually nothing of lasting significance for Afghanistan.

The contracting business is dominated by warlords and former mujahedin commanders, many of the same figures who terrorized the Afghan population in the early 1990s before the Taliban kicked them out. Now those warlords have a stranglehold on the surfeit of aid money, and on the top posts in the Kabul government. It’s no surprise that few Afghans feel any warmth for President Karzai and his allies: they’re robbing the people blind. Several estimates place the total dollar amount of bribes paid by the Afghan people at $3 billion annually, roughly half a billion more than the government collects in taxes. Villagers pay petty bribes to local cops and officials, and the fat cats pay bribes to senior government ministers; the system is riddled through and through with corruption. Such is progress.

The Taliban, too, have soiled their hands. The Afghan narcotics trade, which currently supplies 90 percent of the world’s heroin, is widely believed to be the Taliban’s chief source of revenue. They also generate income by taxing the Afghan shipping companies that ISAF pays to truck in the supplies that keep the armies running. When the trucking companies refuse to pay, the Taliban—or whoever happens to be wearing a Taliban turban that day—attack a convoy and burn a tanker. The “warning” drives up the shipping costs and justifies the role of the Afghan security companies that protect the convoys. There’s more than a little suspicion that Afghan tails are wagging the American dog.

Meanwhile, the insurgency has metastasized throughout the entire country, and suicide bombings and IED attacks are killing hundreds of civilians each month. Figures close to the government are being picked off, from police chiefs and district governors to the president’s own half-brother, Kandahari powerbroker Ahmed Wali Karzai. Ahmed Wali was tied to the CIA through a controversial militia (read: hit squad) program called the Kandahar Strike Force, but he was also rumored to have links with the flourishing drug trade. In July 2011, a trusted associate shot Ahmed Wali point blank in the face for reasons that will probably always remain murky. Another of the president’s brothers, Mahmoud Karzai, was the beneficiary of $200 million in fraudulent loans issued by the Kabul Bank, from which a grand total of $900 million is currently AWOL.

You have to try very, very hard to convince yourself that this country isn’t hurtling toward meltdown. And now the announcement that a third of America’s 100,000 troops will depart Afghanistan by the end of 2012. One thing is certain: we’re past the climax of foreign military and financial presence here. Let the prolonged and savage denouement begin.

This is the Afghanistan in which Assad Parvanta still sees a sliver of hope, though it’s getting harder and harder. A few years ago, he developed crippling stomach pains that would seize him suddenly and without warning. He saw a gastroenterologist, but the doctor told him he didn’t have an ulcer. All the tests showed he was perfectly healthy. Ditto on the oncologist. Finally, a family doctor diagnosed him with conversion disorder; the chronic stress of the property dispute was manifesting itself in excruciating physical pain. “That’s when I discovered Xanax,” he laughs.

Then, on February 26, 2010, Kabul almost killed him outright. Assad was staying in the Park Residence guesthouse in Shar-e-Now. He’d tossed and turned all night, anxious about the dubious results of yet another trip. So he was wide awake at six-thirty on that dreary morning when an enormous explosion threw him clean out of bed. Kabul is near a fault line, and Assad was sure there’d been an earthquake. The force was so powerful, it seemed like the Safi Landmark next door would crash right down on his head. He rushed to the door and saw a worker in the courtyard, looking terrified. “What happened?” Assad screamed, but before the worker could answer, a secondary blast knocked him to the ground. Then the sky split open with the sound of automatic fire.

“This all happened in a matter of a few seconds,” Assad remembers. “My room was just destroyed—shattered glass all over the floor, clothes everywhere.” Assad pulled on his sneakers, grabbed his jacket, and ran for the stairs. When he reached the courtyard below, some of the cooks were racing for cover in the basement. “Come with us, Mr. Assad!” they yelled, but Assad had seen a man dressed in what looked like a security guard’s uniform, carrying a weapon, bandoliers strapped across his chest. He knew all the guards, and realized he didn’t recognize the man, who was going from room to room, throwing small objects through the broken ground floor windows. Only later did he realize the man was tossing grenades.

Assad stood behind a wall, determined to make a break for a bamboo ladder in the garden that led to the roof. Just as he was about to go for it, another one of the staff ran down the stairs behind him, yelling for Assad to follow. The cook ran straight into the gunsights of one of the attackers, who cut him down with a burst from his AK-47. Assad bolted, made it to the ladder, and leapt onto the roof. He hid for a moment behind a pile of sandbags that had been abandoned by the guards, but he could hear bullets smacking into the wall he’d just come over, and he knew he couldn’t stay where he was. Using his leather jacket to protect himself from the razor wire, he rolled over the exterior wall and jumped to the street below. As he ran across the street to safety, bloodcurdling yells stopped him cold.

“Halt!” the men were yelling. “We’ll shoot!” The guards from the buildings across the street were hiding behind whatever they could find, and all of their barrels were aimed at Assad. “They didn’t know if I was a suicide bomber or not, they were terrified,” he says. “I yelled that I was a guest at the hotel, but they said they didn’t care. If I moved one more inch, they would kill me.”

On another side street, Assad faced the same thing from a line of Ministry of Interior policemen. Finally, a guard of a residential building let him inside, where he helped bandage two badly wounded survivors who’d seen him running and followed him. By the time the attackers had fired all their shells and pulled the cords on their suicide vests, eighteen people were dead.

“My family supports me a hundred percent,” Assad confides. “They’ve all given me their power of attorney, but they don’t have the investment in it that I do.” Abe, the oldest Parvanta child, who worked for most of his career as a nutritionist with the Centers for Disease Control, spent so much of his childhood abroad that he struggles to read and write Farsi. Farrukh never married; she takes care of Assad’s mother, who turned eighty this year. Fruzan, whose husband owns a large health food retail chain, lives a comfortable life with her children. “They’re just not the kind of people who would pursue something like this,” Assad says. His children, teenagers now, are fully Americanized. They speak a little Dari, but they have no connection to their father’s country. The property dispute and the development plans are Assad’s albatross to wear, alone. And the two-story building is all that remains of his Kabul.

“To be honest,” he says, “even when I came here in 2002 I knew in the bottom of my heart that I would never bring my family to live here.” Little by little, he’s been forced to abandon the plans he had to finish his father’s building. He’ll never have the capital or the pull to get past the zoning commissioners—and, besides, if he did finish it, he’d be stuck making more trips to Afghanistan to manage the tenants. His wife would kill him at the mere suggestion of another ten years like this. Over the decade since September 11, he’s poured so much of himself into this problem that he doesn’t know what he’ll do with himself once it’s all over.

“I’ve been thinking recently I should just find a buyer and get out while I can,” he says, exhausted. “I’m still young. I could go take the money from the sale and try to start something new.”

We talk about stopping at a kebab shop for lunch on our way home, but Assad’s stomach is still touchy, and he opts instead for a clump of Iranian bananas.

“You gotta come out to Denver sometime and try my kebabs,” he grins. “Every Fourth of July, I grill for the whole neighborhood. It’s my favorite holiday. You can smell the smoke from a mile away.”