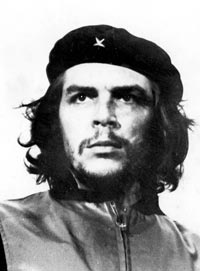

Ecce homo: Ernesto, Fuser, The Argentine, The Heroic Guerrilla, The Shadowy Power Behind Fidel Castro, The Great Compañero, The New Socialist Man, The Last Armed Prophet, The Most Complete Human Being of Our Age, The Clearest, Most Unequivocal Image of the Humanity of the World-Wide Revolutionary Struggle Unfolding Today, Santo Che de La Huigera, El Che, Che.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara was born in Rosario, Argentina, in 1928 and reborn as a revolutionary martyr thirty-nine years later, captured, and summarily executed by the Bolivian military. Or perhaps he was reborn three days after his death, October 10, 1967, when the photograph of his corpse—pale eyes open, surprisingly mild—was transmitted to the world. John Berger immediately noted the photo’s similarity to two Renaissance paintings, one ultra secular and the other nouveau sacred: Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulip” and Mantegna’s painting of the dead Christ.

Within eighteen months of his death, this instant immortal had been embalmed—in the form of Egyptian matinee idol Omar Sharif—by Twentieth Century Fox, as the subject of a tediously self-important and ridiculously old-fashioned Hollywood biopic. Early evidence of the hyperreal: noting the production’s budget, John Leonard observed in the New York Times Magazine that making a movie about revolution was considerably more expensive than the revolution itself, “about $10,000 an hour.” But of course: as director Richard Fleischer told Leonard, “No one had ever heard of Che Guevara until he died.”

The last of the moguls, Darryl F. Zanuck saw his studio’s Che in the tradition of Fox’s 1952 Viva Zapata—a melancholy, heartfelt, prestigious, star-spangled tribute to revolutionary failure. A hardcore New Left action tough guy, this Che equates Yanqui and Soviet imperialism and has no patience for governing. “I’ve had enough,” he tells Castro. The Beard begs him to stay but Che is unmoved. “You want to build socialism on one flea-speck in the Caribbean?” he sneers before leaving for his date with destiny. The last word is given to an old Bolivian peon who, hating Che and the government equally, had informed the authorities. His question is delivered to the spectator: “Why do people in your country flock to see a dead gangster?”1

The closest thing to a rock star that international Communism ever produced has reemerged as a capitalist tool.

Why indeed? For forty years following World War II, revolutionary struggle was largely synonymous with guerrilla warfare, and the 1959 Cuban revolution was understood as that struggle’s most improbable success. “For once revolution was experienced as collective honeymoon,” Eric Hobsbawm would write years later; the New Left, he noted, was mobilized by its support for Third World guerrillas and, in the US at least, its “resistance to being sent to fight against them.”

Is dead Che the signifier of revolution or the poster boy for repressive tolerance—not to mention co-optive commodification? Is our Che as famous as Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp? Does his scruffy beard emblazon more T-shirts than Mickey Mouse—not to mention beer cans, finger puppets, and chocolate cigars? Several years ago, a children’s boutique in haute boho Williamsburg achieved a certain notoriety for marketing Che kiddie-wear. And yet some vestige of authenticity must somewhere remain—if only as guilt by association. In 2006, Sinn Fein president Gerry Adams was banned from the opening night party at a Victoria and Albert Museum exhibit devoted entirely to the many manifestations of Alberto Korda’s world-historic photograph “Guerrillero Heroico” and, as the New York Times reported last July 4, the Colombian commandos who freed fifteen hostages, including Ingrid Betancourt, disguised themselves by wearing Che T-shirts.

Unlike Stalin or Hitler or Mao (or Enver Hoxha or Kim Il Sung), dictators who lived a cult of personality, Che’s career as an icon—and a fashion statement—has been almost entirely posthumous. Still, he was an international political celebrity before he turned thirty-two. During that same year Che first graced Time’s cover when Korda snapped the most famous (and appropriated) photographic portrait of all time. Every aspiration to which the New Left dared dream was embodied in Che’s image—long hair topped by a perfectly placed black beret and flowing in the winds of change, gaze resolutely focused on anti-imperialist struggle and, unseen, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir on the platform beside him. Che subsumed the old Left. His death upstaged a great Soviet celebration. The fiftieth anniversary of the Glorious October Revolution could scarcely have been less relevant.2

Forget Lenin. “For the first time in its history,” Herbert Read declared, “the communist movement has found a romantic hero, a man in the tradition of Count Roland or the Black Prince.” And for Graham Greene, Che “represented the idea of gallantry, chivalry, and adventure in a world more and more given up to business arrangements between the great world powers.” The editors of the October 1968 issue of Fortune seemed surprised to discover that on American campuses Che was more popular than Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, and George Wallace—if not Jimi, Janis, and Bob Dylan.

The dorm room pin-up was relegated to the attic of cultural memory well before the seventies ended—at least outside of Cuba. There, with the day of his death a national day of mourning, he served as the model for generations of schoolchildren as well as a source for the handicrafts sold in hard currency as souvenirs to visiting leftists. Fifteen years after Che’s demise, Pedro Haskell, a Chilean exile living in Havana, made the most poignant expression of those faded hopes. The subject of his grainy, crude A Photograph Circles the World is the Heroic Guerrilla—or rather, Korda’s image of the HG as it is painted on buildings, stenciled on walls, printed on placards, born on banners in street demonstrations throughout Europe and the Americas, hero of mechanical reproduction.

With the end of the Cold War, the trademark was hijacked! As anticipated by Olivetti’s appropriation of Che’s image for an ad in the late sixties celebrating their creative sales force (“We would have hired him”), the closest thing to a rock star that international Communism ever produced reemerged as a capitalist tool. And as Bill Clinton brought the Sixties Generation to power in the mid-nineties, his old comrade Che was emblazoned on a top-selling Swatch watch. The Heroic Guerrilla became more ubiquitous than the Mona Lisa. Just before Clinton’s reelection, Che re-reappeared in a new romantic guise, as the footloose protagonist of a hitherto unknown journal published as The Motorcycle Diaries.3

The mantle of American public enemy number one had passed from Ayatollah Khomeini to Muammar Qaddafi to Saddam Hussein to Osama bin Laden (like Che, a stateless revolutionary absolutist). The personification of Third World revolution was now the embodiment of free-market globalism and free-floating youthful exuberance as well as a mask affixed, willingly or otherwise, to pop stars (Madonna, Cher), American politicians (John Kerry, Ralph Nader), and fellow martyred celebrities (Princess Diana, Jesus Christ).

“Guerrilla Warfare taught that in order to win, one must dare to try and in order to dare, one must have faith. Che endowed two generations of young people with the tools of that faith, and the fervor of that conviction. But he must also be held responsible for the wasted blood and lives that decimated those generations. His all too costly errors included his emphasis on technical and military matters; the lessons he drew from watching only half of a very complex film.”

—Jorge G. Castaneda, Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara

The very least that one can say for Steven Soderbergh’s unlikely epic, the latest addition to the Book of Che—a two-part four-and-a-half-hour case study representing Guevara first as a victorious guerrilla leader in the Sierra Maestra and then, a decade later, as a defeated guerrilla leader in the Andes—is that it attempts to provide both halves of that very complex film. The miracle of Cuba is complemented by the disaster of Bolivia.

Che remains a film object—a thing to be experienced. The movie demands to take its time, with both parts taken in at a single sitting.

Premiered amid the hurly-burly of the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, Soderbergh’s $65 million rumination was characterized by a detached objectivity that might well have been approved by Roberto Rossellini; it displayed a virtuoso sweep that could have been envied by Francis Coppola and claimed a subject that surely fascinated Oliver Stone. The concern for verisimilitude might even have been appreciated by its subject. (Soderbergh’s sources were primary: Guevara’s Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War and Bolivian Diary.)

Che seemed perhaps a great movie and certainly something no less rare—a magnificently uncommercial folly. For who in 2008 could possibly want an American movie on the minutiae of guerrilla warfare? And so, this undertaking adds another puzzlement to Soderbergh’s enigmatic career. Having more or less put US independent film on the map when Sex, Lies, and Videotape won an award at the Sundance Film Festival in 1989, the filmmaker has alternated between accomplished commercial flicks (most successfully Erin Brockovich and Ocean’s 11) and pretentious, scruffy narrative experiments. Soderbergh’s 2000 dope opera Traffic came nearest to reconciling these seemingly antithetic modes. But so, in its way, does Che. The first half, known as The Argentine, has the look of classic Hollywood cinema; the second, The Guerrilla, is more rough-and-ready cinéma vérité.

Many initial viewers were confounded to the degree that Che appeared as a non- or even an anti-biopic. Despite a stellar performance by Benicio Del Toro, who had initiated the project some years ago with Soderbergh as producer and Terrence Malick attached as writer and director, Che presents its subject almost entirely as the protagonist in the context of two specific events. Moreover, the director seemed to keep his distance and reserve his judgment. Skillfully didactic, as well as nervily dialectical, this feel-good/feel-bad combat film thus had less in common with the touchy-feely Motorcycle Diaries than with Peter Watkins’s spare, self-reflexive reconstruction of the Paris Commune, La Commune (Paris, 1871). And, while Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 Battle of Algiers, the most celebrated application of a neo-realist methodology to recent history, might provide another corollary, Soderbergh’s measured formalism—at least at first look—was so pronounced that Che seemed akin to a structuralist extravaganza like Michael Snow’s machine-driven landscape study La Région Centrale.

Since then, Soderbergh has tweaked his movie’s first half in ways that soften its strangeness and blunt its intellectual edge. Most obviously, a number of mock cinéma vérité flash-forwards have been added to The Argentine, enabling the protagonist to address his Anglophone audience with a lightly accented English-language voiceover. Annotating the past with the “present” and tightening the movie’s overall sound/image connections, these inserts do allow for another sort of dialectic, but their presence serves to subtly normalize Soderbergh’s distancing strategy. (Or what was taken to be his strategy. “With all the subtitles, we thought it was Jean-Luc Godard,” a colleague joked.) More crucial is Soderbergh’s shortening of certain choreographed battle scenes and the omission of a five- or six-minute sequence concerning the trial of Lalo Sardiñas which served to demonstrate application of guerrilla justice.4

Even so, Che remains a film object—that is, a thing to be experienced. The movie demands to take its time, with both parts taken in at a single sitting. Each half begins with the leisurely contemplation of a map—first Cuba, then Bolivia in the context of Latin America—as if to emphasize the dictatorship of place, rather than the proletariat. Soderbergh’s coolly single-minded meditation on the practice of guerrilla warfare (as well as the creation of militant superstardom and the nature of objective camera work) is at once visceral and intellectual, sumptuous and painful, boldly simplified and massively detailed.

A fragmentary introduction jumps from black-and-white Havana 1964 (Che is asked by an English-speaking interviewer if reform throughout Latin America might not blunt the “message of the Cuban Revolution”) back to the 1952 military coup that returned General Fulgencio Batista to power, then vaults ahead three years to a gathering in Mexico City where Che first meets Fidel, hears his analysis, comes to appreciate his faith, and signs on as a disciple. (The audience learns that of the eighty-two original guerrillas who followed Castro into the Sierra Maestra only twelve survived to see the victorious revolution.) Concluding this brief précis of the causes, context, and culmination of Castro’s revolution with a return to 1964 (and vérité-style black and white) for Che’s address before the United Nations, Che takes to the hills.

March 1957: the asthmatic Argentine doctor enters wheezing and, anticipating another major issue in the movie’s second half, must immediately deal with his role as a foreign presence in someone else’s revolution. Soon after, Soderbergh addresses the notion of destiny. The boldness of the guerrillas’ May 28, 1957, attack on the army barracks is portrayed as a daring tactical maneuver. In the midst of the battle, one guerrilla boasts that he has a saint watching over him. As might have happened in a Sam Fuller combat movie, he immediately takes a bullet and falls down dead: History is made by men, if not necessarily under circumstances of their own choosing. Soderbergh goes on to reinforce Castro’s grasp of strategy (the recognition that whoever takes the Sierra Maestra takes Cuba), his political smarts (the capacity to coordinate his uprising with other groups while maintaining control over the revolution), and mainly his organizational genius (the creation and administration of “liberated territory”) although this talent is most apparent by its absence in The Guerrilla.

While Demián Bichir’s Castro impersonation successfully mimics the leader’s rolling, precise diction, rambling, imprecise grammar, unlikely tenor and distinctive theatrical gestures, Del Toro’s Che functions as the symbol of the revolution—the greatest of foot soldiers. Far from swashbuckling Omar Sharif or doe-eyed Gael Garcia Bernal, Che’s protagonist is self-effacing and strict. A sometimes bombastic performer, bulky yet sure-footed, and given very few close-ups (and those mainly in the glamorous New York in 1964 sequences), Del Toro assumes this burden and carries it uphill through both halves of the movie.

It’s in Santa Clara’s giddy aftermath that Soderbergh reveals Che’s essence. The successful revolutionary angrily de-confiscates the stolen T-Bird in which several guerrillas are joyriding toward the capital and sends them back to return the car. Che’s victory confirms his moral code. Equally ascetic, Soderbergh eschews the ecstatic entrance into Havana, the better to lay the groundwork for Che’s attempt to repeat the unrepeatable under more difficult circumstances in less hospitable terrain.

The lush Sierra Maestra gives way to something more arid and autumnal. Che’s second half is even more concerned with process. The passion is constant and so are the problems: The guerrillas lack discipline, the peasants are resistant, government soldiers are too depressed or fatalistic to be recruited, and Che himself seems unable to understand that Bolivia is not Cuba. It was while he was in Bolivia that Che called for “two, three, many Vietnams”—unavoidably ironic in that Bolivia afforded the US an opportunity to successfully deploy tactics designed for Vietnam.

The Bolivian campaign is a grim story straightforwardly told. A brief montage touches on Che’s decision to leave Cuba. Arriving in Bolivia disguised as a middle-aged Uruguayan businessman, he drives into the mountains to meet his men. In a reverse countdown to doom, the movie is structured by the days elapsed since Che’s arrival in country. Day 26 has a mood of happy solidarity, despite the issue of the leader’s foreign-ness. By Day 67, however, Che has already been set up for betrayal; trying to reach the peasants, he has only caused one to think that he and his men must be cocaine smugglers.

Thirty-three days later, there’s a shortage of food and Che has to exercise revolutionary discipline to resolve conflicts between his Cuban and Bolivian followers. By Day 113, some of the guerrillas have deserted and the Bolivian army has discovered their base camp. Military planes are flying overhead; it’s apparent that, her head clouded by romantic enthusiasm, Che’s revolutionary contact Tania (German actress Franka Potente) has botched the elaborate preparations and inadvertently given away their identity. “Five years, Tania!” Che exclaims. But the timer cannot be reset at zero.

On Day 141, the guerrillas capture some Bolivian soldiers who, however much they may hate their commanding officers, are less interested in joining the revolution than in returning to their villages. In any case, it is the Bolivian government that is accruing power. Soon, CIA advisors—notably a blandly sinister Matt Damon—arrive to supervise anti-insurgent activity and training. Shortly after, on Day 169, Che’s French buddy and chronicler Régis Debray is captured. The Bolivian army launches its first real aerial attack on Day 219.

Che is an act of will rather than a work of art, overtly concerned with technical issues—the revolution’s and its own.

Che grows ill and by Day 280 can barely breathe. Riding a recalcitrant white horse, the hero tumbles off, then tries to lead it by the bridle and, in his maddened frustration, is finally reduced to beating the animal. Although the scene might seem a metaphor for Che’s attempt to educate Bolivian villagers, he never uses force against the population. But neither does he ever learn from them—perhaps he himself is the white horse. (“We are fighting for the poor, for the humble people, but they have never helped us,” he noted in his diary.)

Is Che a form of tragic socialist realism? Political meetings are a study in applied discipline; the guerrillas are continually purging their ranks. Certainly, the hero never changes but only refines his perfect being. But the lessons learned in the Sierra Maestra have no application in the unrelentingly grim suicide mission that Che contrived for himself in Bolivia.5

If Che has struck some critics as essentially self-reflexive—that is, as a movie essentially concerned with its own making—it may be because Soderbergh is less a driven auteur or even an enthusiastic cinephile than he is a highly intelligent technician who sets himself a problem and goes about solving it.6

It’s indicative of Soderbergh’s interest in the nuts and bolts of production that, almost alone among American directors, he serves (under a pseudonym) as his own director of photography. Given this workmanlike attitude, Soderbergh could hardly have failed to appreciate Che’s last letter to his parents, speaking as it does of the “will-power” that he had “polished with an artist’s attention.” Che is an act of will (two halves shot back-to-back in reverse order, with thirty-nine days scheduled for each) rather than a work of art, overtly concerned with technical issues—the revolution’s and its own. Suggesting a relationship between filmed and actual revolution inversion that John Leonard noted on the set of the 1969 Che, Soderbergh told Amy Taubin that what interested him most “was the process and the physical difficulty . . . I wanted to show day to day stuff—things that have meaning on a practical level and on an ideological level.”

Soderbergh has emphasized his use of a lightweight high-performance digital cine camera prototype (“shooting with RED [was] like hearing the Beatles for the first time”) and indeed Che is superb filmmaking—forcefully edited, purposefully repetitive. Everything is foreshadowed; each sequence has its parallel. There is no scene that cannot be seen as part of an ongoing argument. Moving on two tracks, The Argentine in particular requires an unusually active viewer. After a scene in which Che pronounces a death sentence on a pair of rogue guerrillas, Soderbergh jumps into the future to show the UN surrounded by passionate anti-Castro demonstrators and under bomb threat. As the Nicaraguan and Panamanian UN delegates register complaints about revolutionary Cuba, the guerrilla base—a functioning community—comes under air attack six years earlier. Che answers his critics and then it’s back to October 15, 1958, with the guerrillas approaching the town of Las Villas, hidden (like their future) in the clouds.

The Argentine devotes the greatest amount of screen time to the Battle of Santa Clara. As the guerrillas engage in street-to-street fighting, taking the church (to take advantage of its steeple), this set suggests the Florence episode from Rosselini’s Paisan. There’s a clarity to the confusion. In other ways, notably the use of Guevara as a constantly speaking subject (addressing the townspeople, negotiating the local commander’s surrender on bluff and bravado), the sequence resembles one of Rossellini’s late historical films. Here, as in The Age of the Medici or Blaise Pascal, action is the materialization of thought, as is the filmmaker’s use of homogenous space, functional montage, and unobtrusive period mise en scène. Nothing distracts from the spectacle of men making history—or not.

What follows is something else. In keeping with traditional Che martyrology, Soderbergh originally intended to make only his epic’s second half. But although it’s arguable that The Guerrilla is the more realized of Che’s two parts, it is only comprehensible in the light of The Argentine. The Guerrilla is a great sixties disaster movie, comparable in some ways to the Japanese filmmaker Kôji Wakamatsu’s recent United Red Army—an engrossing but grueling dramatization of student radicalism from the 1960 security-treaty demonstrations through the anti–Vietnam War demos and the militant “World revolution!” of 1968 into self-devouring sectarian madness. What both movies have in common is a critique of the Left’s hopeless, self-devouring attempts to change reality. But unlike the militants of the URA, who may be considered in some ways Che’s children, Che became an authentic martyr. The Argentine elevates The Guerrilla to tragedy.7

Thought is dematerialized. In the final days of their enterprise, Che and his men are first ambushed and routed, then outsmarted and, on Day 340, trapped by the Bolivian army. Che is captured and questioned (discussing religion and family with his guards). On Day 341, October 9, 1967, the chopper lands and a Cuban exile climbs out, greeting the prisoner with an accusatory, “You executed my uncle.” Che can only nod. The Americans are phoned and with their permission the execution is executed. Soderbergh allows Che a close-up at the moment when he faces death and, in fact, demands it, commanding the nervous soldier to shoot him. The filmmaker even indulges in a single subjective shot: Che’s view of the hut’s dirt floor dissolves into nothingness.

The century’s most famous corpse—the corpse of more than an individual man—is photographed and ascends heavenward in a helicopter. Cut to the young Che of twenty years before, bound for Cuba on the Granma. Soderbergh has given us Che: The Process and Che: The Passion. We are already familiar with the resurrection.

Notes

- Che was presciently advertised as presenting the personification of the sixties: “With a Dream of Justice, He Created a Nightmare of Violence!” During its opening week in New York, someone lobbed a hand-grenade into Loews Orpheum one morning at 4 a.m.; in Los Angeles, several Molotov cocktails were tossed over the studio lot wall and a theater was set on fire. The gestures were superfluous. The movie was a famous box office disaster. ↩

- Significantly, Korda’s portrait was not published abroad until August 1967; it appeared as part of Che’s legend, during the period when, as John Berger wrote, “Nobody knew for certain where he was. There was no incontestable evidence of anyone having seen him. But his presence was constantly assumed and invoked.” Korda’s photograph was thus the last image of the living Che and the first image of myth to come. In the aftermath of Che’s death, Castro addressed a memorial rally at Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución standing before a five story high blow-up of the photograph. (New versions were used in subsequent years; now a metal silhouette is permanently affixed on the Ministry of the Interior’s exterior.) “Heroic Guerrilla” emblazoned the cover and advertisements for the Italian edition of Che’s Bolivian Diary, first published in spring 1968, and thereafter became the presiding deity in the student demonstrations shown in Haskell’s film. ↩

- Even outside of Cuba, serious Che art—Jay Cantor’s historical novel The Death of Che Guevara or Richard Dindo’s documentary Ernesto Che Guevara: The Bolivian Diary —has tended to concern Che’s martyrdom. But that was before The Motorcycle Diaries. Withheld from publication until 1995 (and still omitted from Cuba’s “authorized” Guevara canon), Che’s rewritten journal of a youthful road trip taken in the company of fellow medical student Alberto Granado sold a fast 30,000 copies in a Verso paperback blurbed as “Das Kapital meets Easy Rider.” A new generation of devotees was thrilled to discover the young Che as a romantic, poetry-reading hipster. The 2005 film version of The Motorcycle Diaries was masterminded by its executive producer Robert Redford, who recruited Brazilian director (and Sundance Institute alumnus) Walter Salles to make the film—in Spanish, with a Latin American cast. Che, or “Fuser” as his comrade calls him, is played by the young Mexican star Gael Garcia Bernal, who had already played Che in the 2002 Showtime mini-series Fidel. ↩

- In Che’s absence, his subordinate Lalo Sardiñas inadvertently killed an unruly comrade—or, by some accounts, an insubordinate peasant. Sardiñas was placed in custody and, after an open trial found him guilty, Castro organized an election to determine his punishment. There were seventy votes for death and seventy-seven for another punishment—which turned out to be a demotion and assignment to hazardous duty. Cuba has not had an open election since. ↩

- In his 1994 documentary Ernest Che Guevara: The Bolivian Diary, Swiss filmmaker Richard Dindo austerely evokes Che’s eleven-month Bolivian campaign—documenting the scene of Che’s last stand, interviewing surviving witnesses, and having New Left filmmaker Robert Kramer read the diary. Four years later, American avant-garde filmmaker James Benning created an even more economical re-telling by grafting Dindo’s soundtrack onto a series of “empty” landscapes shot in and around Death Valley. Benning’s Utopia is predicated on a tangible absence. The timeless vistas echo with once world-historical derring-do and overheated rhetoric, even after the desert gives way to a succession of refineries, mines, and motels. ↩

- So far this century, Soderbergh has made two sequels to his Ocean’s 11 remake, a remake of Tarkovsky’s Solaris (2002), a pair of digital films—the elaborately self-reflexive exposé of soul-killing Hollywood Full Frontal (2002) and an aggressively banal nouveau neo-realist account of Ohio factory workers Bubble (2005)—as well as The Good German (2006), a simulation of a 1940s private-eye flick in that it is not just a period film but one that feigns being shot in that period. ↩

- Just as Soderbergh is fascinated with the disintegration of Che’s Bolivian adventure, so Wakamatsu seems most interested in what happened at the URA’s isolated training camp in late ’71 and early ’72. The heart of United Red Army are the prolonged, increasingly violent, self-criticism sessions—an escalating, claustrophobic, paranoid reign of terror, staged in near darkness and shown in close-up as, day by day, the group tears itself apart, beating and eventually executing its supposed heretics. ↩