On July 14, 1959, the Richmond News Leader ran an editorial by Ezra Pound entitled “Keynes Brainwashed Electorate with Economic Hogwash.” It was his first and last publication in the Virginia newspaper—despite a yearlong stint as its foreign correspondent in Europe. In typical Pound style, it was a scathing swipe at the English economist, occasioned by an article that Pound had not bothered to read. Nevertheless, his editor, James J. Kilpatrick, was relieved to find the article publishable. Since the previous summer, Pound had been submitting letters and articles from Italy on a handful of topics, usually politics, none of which Kilpatrick had deemed coherent enough to run. In a letter to a friend, Pound said he had written this last piece in “what I believe is clear and simple (as he request) language.”

The bulk of Pound’s feisty, allusive writing for the paper, however, remained unprinted and unknown, buried in Kilpatrick’s desk drawer—it was “over Richmond’s head,” Pound proposed—until it eventually was donated to the University of Virginia Library. Assembled in print here, for the first time, these eight pieces represent some of the preoccupations, musings, and typically bold assertions of the physically and mentally aging poet in his final period of sustained energetic writing and correspondence. They also illuminate a nearly forgotten moment in Pound’s life—a crucial late crossroads, when he briefly considered taking Virginia, instead of Italy, as his final home.

The story of Pound’s unlikely contributions to the News Leader stretches back to 1941, when he began recording his notorious broadcasts for Radio Rome’s “The American Hour.” His talks usually devolved into slanderous, hate-spewing rants, ravaging Churchill and Roosevelt and attacking any other person or institution he decided was in cahoots with the “Anglo-Jewish clique … out … for the obliteration of Europe.” In fact, his broadcasts were at times nearly incomprehensible, sounding like hyper-politicized Cantos with their wild associations and assumptions, sudden American dialects, and general jibber-jabber. The FBI turned out to be Pound’s main audience.

After the Allies invaded Italy and made their way up the peninsula, Pound was arrested and delivered to the Americans by two Fascist turncoats. He was taken into custody and brought to the Disciplinary Training Center, a facility for the detritus of the American army. He was kept in a six-by-six-foot “gorilla” cage, exposed to dust, the scorching sun, occasional downpours, and the permanent stare of a searchlight. Three weeks later, Pound collapsed and suffered a mental breakdown. He was eventually flown to Washington DC, to answer nineteen counts of treason. His lawyer (he originally requested to represent himself, but the judge refused) entered an insanity plea, and Pound was taken to a nearby hospital to be examined by a team of psychologists. A few weeks later, he was declared mentally unfit to stand trial and was transferred to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, the capitol’s federal institution for the insane, to serve an indeterminate sentence.

For the next twelve years, Pound held court in the Chestnut Ward of St. Elizabeth’s. The writers, critics, scholars, and activists not disgusted with the infamous poet flocked there to visit him, and it was an active period for Pound despite his confinement. He became used to interruptions while entertaining guests, writing letters, or working on his Cantos; often inmates would wander mindlessly into his room to stare blankly or whisper in his ear. Archibald MacLeish, a longtime friend who had worked tirelessly for Pound’s release, wrote that after a visit to St. Elizabeth’s, “[y]ou carry the horror away with you like the smell of the ward in your clothes, and whenever afterward you think of Pound or read his lines a stale sorrow afflicts you.” After reading MacLeish’s comments, Harry Meacham, a Richmond businessman and the president of the Virginia Poetry Society, felt he could no longer sit still while one of America’s greatest poetic minds rotted away in the nuthouse.

On April 6, 1957, Meacham spent the afternoon with Pound and his wife, Dorothy Shakespear Pound, discussing poetry, education, and the public. The group hit it off, and Meacham let Pound know he was willing to help in any way he could, later writing to Dorothy, “The proposition is not justice, but freedom.” Meacham contacted MacLeish, Ernest Hemingway, and other influential figures to form a campaign to help free Ezra Pound. Meacham also persuaded James J. Kilpatrick, the editor of the News Leader, to write an editorial calling for Pound’s release. Up to that point, few newspapers or journals had been willing to write anything on Pound’s behalf. Kilpatrick’s editorial—bluntly titled “Ezra Pound: Set Him Free!”—questioned the motives of a Justice Department that had “forgiven every other enemy of World War II” and wondered what “useful purpose is served by keeping Pound locked up in St. Elizabeth’s.” The editorial was picked up by the press and circulated widely.

As sympathy built for Pound on the strength of Kilpatrick editorial, Meacham brought the poet a copy of the Virginia Quarterly Review, and Pound, impressed by the magazine, decided to submit “Canto XCIX” for publication. VQR editor Charlotte Kohler enthusiastically accepted the poem, and an elated Pound wrote Meacham the same day. “Va. Quarterly heard from. Just what use is being made of the stables at Monticello?? I liked the look of Charlottesville in 1939.” Pound had often told Meacham he thought he might enjoy living on the grounds of Monticello and apparently any vacancy would do. Over the months, Pound became increasingly friendly with Kohler, Kilpatrick, and John Cook Wyllie, the Librarian at the University of Virginia. He told Meacham that “with yr Editor (R. News L/r), librarian and edt. Vay you have a group or vortex” in the literary scene of America. Pound was corresponding heavily with each member of this Southern vortex, discussing education, book reviews, authors worth publishing, and general notes and news.

By the end of 1957, public opinion seemed to have shifted regarding Pound. T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, and Ernest Hemingway signed a letter drafted by MacLeish to the attorney general pleading Pound’s case. The government reopened the investigation, and MacLeish set up meetings between Frost and the new attorney general. On April 18, 1958, the case went to trial, and the United States dropped the charges against Ezra Pound. By the following night, Pound and Meacham were eating Chinese food at a restaurant in Washington DC.

On April 30, Meacham picked up Pound and headed to Richmond. He had arranged for the poet to meet a few members of the Southern vortex, including Kohler and Kilpatrick, at the Rotunda Club in the Jefferson Hotel. Kohler and Pound shared a lively discussion on the relevance of the current quarterlies, Pound calling them “dead from the neck up” and proposing to turn VQR into an international journal by injecting a little excitement and allowing the journal to wrestle with itself. He also suggested Kohler allot him a page or two each issue so he could remind the public that not all literature is written in English.

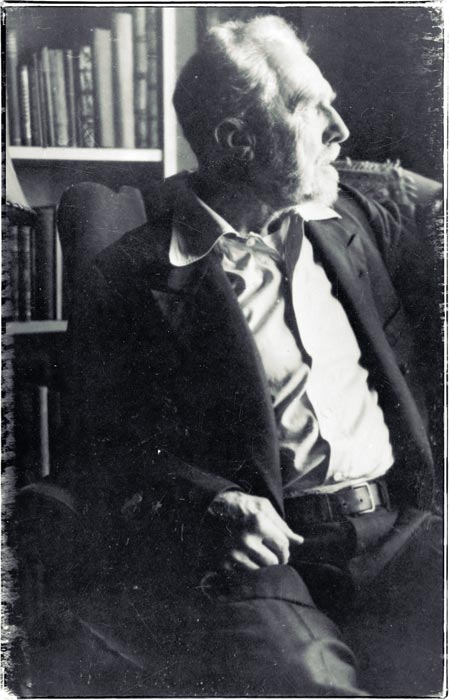

Pound also had agreed to let Kilpatrick interview him that afternoon for an article in the National Review. The “wholly sympathetic … color piece,” in Kilpatrick’s words, emerged as more of an overview of the lunch conversation than an interview with the elusive poet. Kilpatrick recorded observations and snippets of conversation, noting Pound’s theatrical style of dress, continuous speech linked by a thread of coherence, and poor posture (which Pound apologized for, saying, “my head hurts, all of Europe fell on it”). Pound’s sins “are long past,” Kilpatrick wrote. “The nation has forgiven worse offenders.” But if America could not forgive Pound for his particular kind of insanity—the poet famously responded “America is an insane asylum”—then perhaps it was better that he had decided to return to Italy. Kilpatrick concluded, “[I]t seems to me good that at long last, this old Ulysses will go back to Rapallo, there to lie in a raft on the infinite sea, and gaze at the infinite sky.”

Kilpatrick did not let slip in his recounting of lunch that afternoon in Richmond that Pound had proposed the idea of becoming an accredited foreign correspondent for the News Leader. Meacham wrote Kilpatrick a few days later to recommend taking the poet on. “Don’t worry about his incoherence,” Meacham wrote. “This is eccentricity. In formal correspondence he is magnificent.”

Kilpatrick agreed to Pound’s proposal, providing him with credentials—his “papal bull”—to work abroad. Funds were sparse, he said, and the News Leader could offer Pound only $50 or so every few months for a short piece. But assuming Pound was serious and still interested, Kilpatrick closed with a frank outline of his editorial expectations:

I would have to ask you to consider the requirements of a small city daily in terms of style, readability and deference to our readers’ massive ignorance of history both ancient and contemporary. That is intended, by God, as a tactful sentence. What I am trying to say is that writing the Pisan Cantos is one thing, and writing a usable background piece on the Italian elections that is, by me on my editorial page—is another thing. I don’t mean to be offensive; I mean to be honest. Copy would have to be understandable by the reader of mean intelligence, or it would be a waste of your time to write it and mine to print it.

Pound wrote back to Kilpatrick saying he was neither surprised nor concerned by the poor pay, or the creative strictures.

Naturally DEElighted with yr/ advice, and find it totally intelligent because it corresponds so EXactly with my own view of the situation. Of course the 50 bucks wd/ be welcome but the advantages of being a regular correspondent are that I wd/ get 70% reduction on ALL journeys by railroad, instead of the mere 8 or 10 allowed to free lance writers. Idea of getting into conferences etc. is an added bit of sugar.

He said his main goal was simply to make sure Kilpatrick knew what was happening abroad, especially those things that were not likely to make it past the copy desk of the bigger papers. “The strength of an office (news paper office) consisting in its awareness to what is going on. Use of this ammunition wd/ as in warfare, depend on local conditions. As Bonaparte noticed: the effect of artillery due to its being aimed at what you wish to hit.”

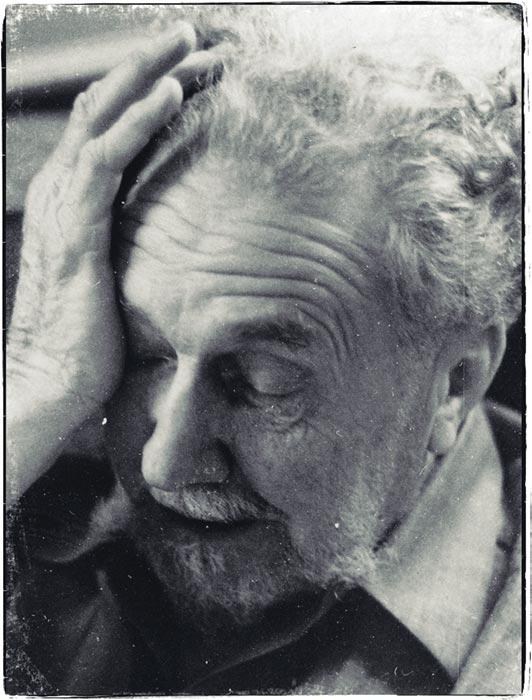

By late May, Kilpatrick had prepared and notarized Pound’s official credentials, dating his passes for 1958 and 1959. A photograph taken at the April 30 gathering in Richmond was used for the picture ID. His assignment for the News Leader was to write about anything European—“politics, elections, belles letters, poetry, finance, the arts.” Whatever interested him was fair game. Pound boarded the SS Cristoforo Colombo en route to Italy bursting with energy.

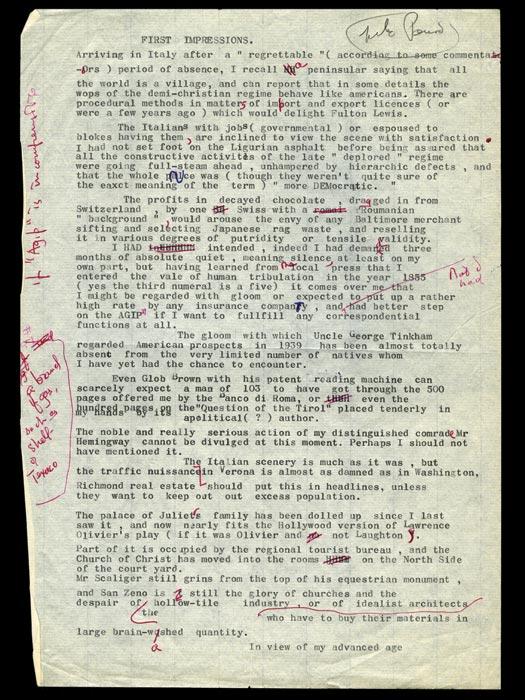

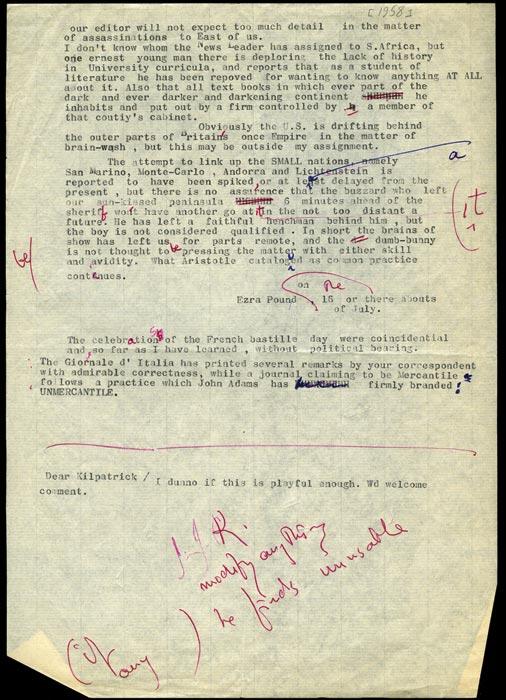

Shortly after arriving in Verona, Pound sent Kilpatrick “First Impressions,” an article which ranged from politics to chocolate, from traffic in Verona to Juliet’s palace—which looked, he said, like a Hollywood movie set. He teased his audience with gossip and retraction—“The noble and really serious action of my distinguished comrade Mr. Hemingway cannot be divulged at this moment. Perhaps I should not have mentioned it.” He sidestepped serious news, writing that due to his “advanced age our editor will not expect too much detail in the matter of assassinations to east of us.” He wrapped up the piece with a flurry of political quips, and a note to the editor at the bottom of the page saying, “Dear Kilpatrick / I dunno if this is playful enough. Wd welcome comment.” Kilpatrick didn’t run the article, nor even try any editorial synthesizing.

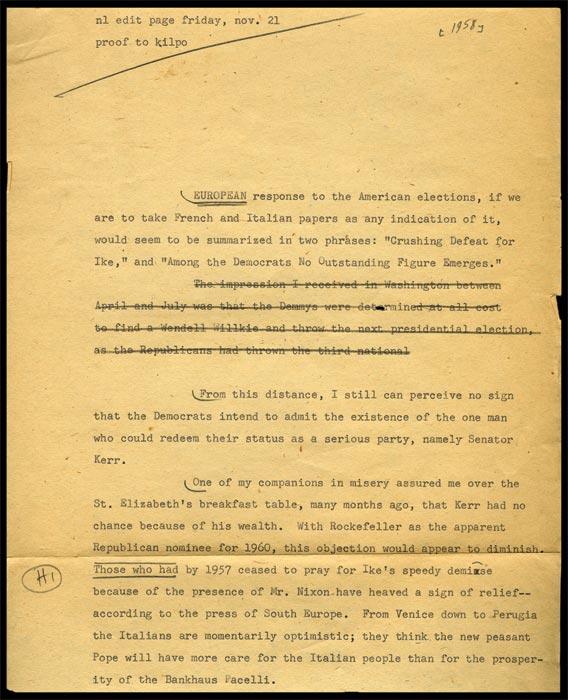

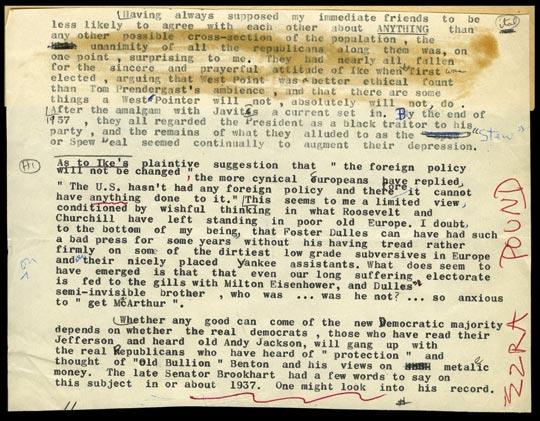

So on November 9, 1958, Pound sent a second attempt, entitled “Repercussions.” It was a short piece on the “European response to American elections,” in which he handed the 1960 Republican presidential nomination to Rockefeller (whom Nixon had already beaten into withdrawing from the race), and called Senator Kerr from Oklahoma the “Demmy’s” only shot at a serious candidate. This article, despite its inaccuracies, made it to proofing, but never appeared in the paper. Kilpatrick wrote Pound what became his standard plea for simplicity, reminding him that readers would rather cozy up for an episode of Gunsmoke than bore through one of Pound’s abstruse and allusive articles.

Pound informed Kilpatrick that he had been working on additional pieces but had “canned several attempts to communicate to R.N.Leader. as not suitable and a mere waste of yr/time. What I do send is primarily for YOUR personal information/ IF of any use, take it and Welcome.” In the margin Pound typed a postscript asking why “Va” stopped “printing Cantos after their solitary splurge??”—still irked that his proposal to become a regular contributor was scuttled by the journal’s advisory board of professors.

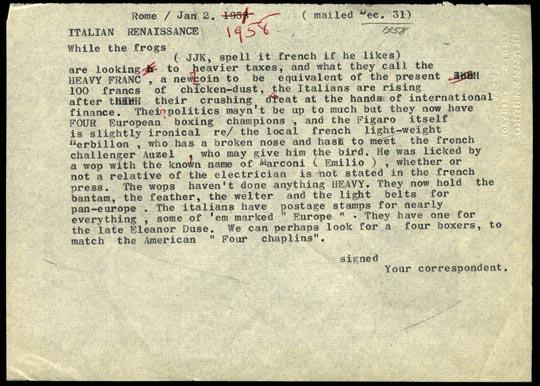

His third contribution—despite a title at the top of the page (“French Elections”)—was essentially a rambling letter. It contained a slew of disjointed “facts,” economic “constellations,” and one mention of the “Va. Univ. LieBURY.” Kilpatrick could, Pound suggested, mold it into something Richmond could swallow, but his contributions were growing increasingly fragmentary. On New Year’s Eve 1958, Pound sent another unprintable article attacking French and Italian politics, ironically titled “Italian Renaissance.” In it, he calls the franc “chicken-dust” and mocks an American postal stamp memorializing four chaplains who drowned in 1943 after giving their lifejackets away to soldiers when a torpedo hit their ship.

That same New Year’s Eve, the Council of the Foreign Press Club in Rome wrote Kilpatrick a brief inquiry regarding Pound’s recent application for admission to the club as a correspondent for the News Leader. Kilpatrick responded candidly, acknowledging that he “designated Mr. Pound our foreign correspondent out of two considerations”—“an act of kindness” and “the hope for some provocative copy.” He went on to say that the second consideration “has yet to materialize … He has sent me half a dozen things, but unfortunately all of them have defied my skills as copy editor.” But Kilpatrick, nevertheless, gave his heartfelt endorsement to Pound, calling him a “stimulating conversationalist, a scholar, a critic, a man of infinite vanities and eccentricities, and altogether a most unconventional and interesting fellow … Some of your group might regard Pound as a fraud, but I doubt if any of your members would find him dull.”

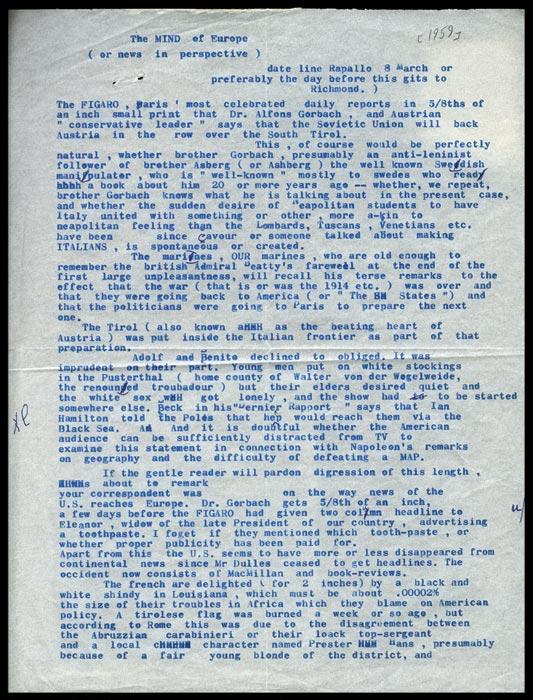

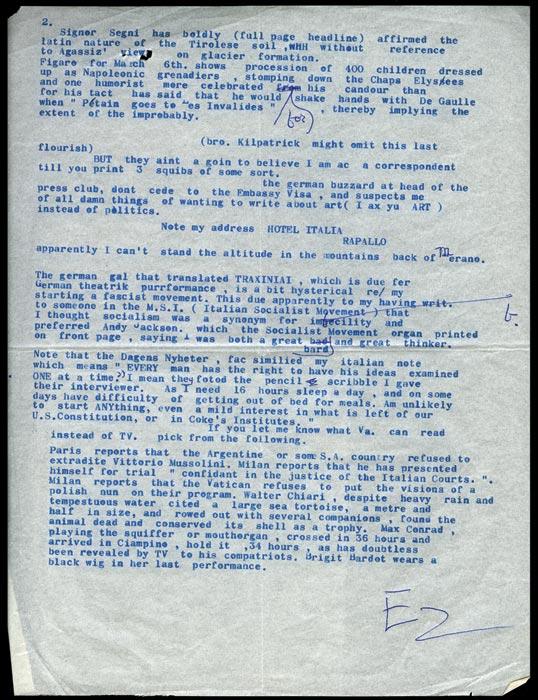

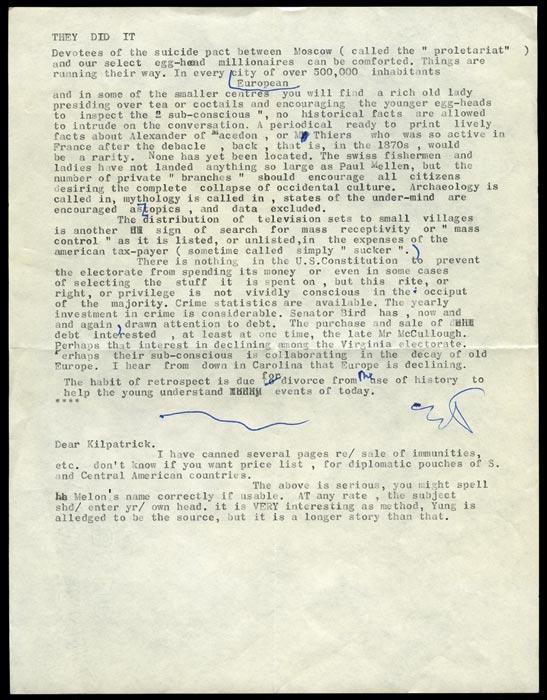

After Kilpatrick declined to print “Italian Renaissance,” Pound sent him “They Did It” and soon after “The MIND of Europe.” By now, he was beginning to fear that his articles were destined for oblivion—and begged Kilpatrick’s consideration: “they aint a goin to believe I am ac a correspondent till you print 3 squibs of some sort.” In closing, he mentioned some recent breathing troubles which had forced him to move from the mountain castle at Brunnenburg to a lower altitude and offered, “If you let me know what Va. can read instead of TV, pick from the following.” His list, however, featured increasingly insipid subject matter, concluding with, “Brigit Bardot wears a black wig in her last performance.”

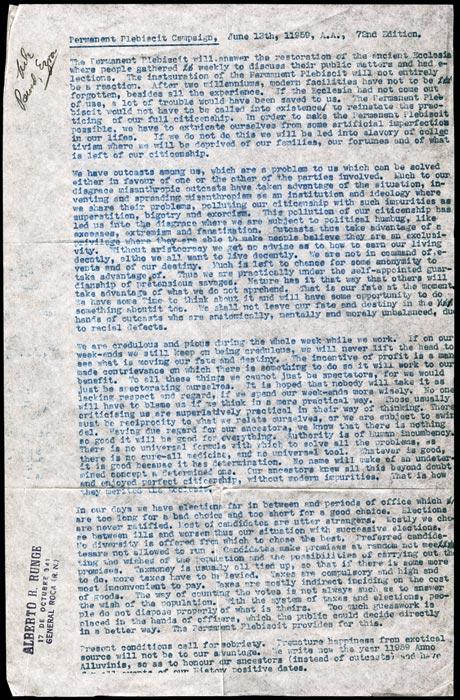

Perhaps regretting his snide remarks, Pound sent Kilpatrick what he considered a serious political proposal—though he gave it the mock-serious name of the “Permanent Plebiscit Campaign.” Pound argued that the ancient methods of lawmaking and governing small groups of people would be the most effective way of dealing with modernity and a shrinking (conceptually) planet and, thus, proposed reclaiming the full rights of citizenship and avoiding collectivist tendencies by removing the inefficient process of electing officials to make decisions the public could decide directly. No response came from Kilpatrick.

Two days later on June 15, 1959, Pound sent a short letter requesting a monthly issue or two of the paper so he “might wake up and get an idea of what you could use.” Pound seemed stubbornly determined to make it into print: “I have saved you several attempts, done a couple months ago. Since when have been settling in nearer the sources of news.” The latest submission and follow-up letter were waiting for Kilpatrick when he returned to Richmond after a three-week trip out west. He responded by re-outlining his expectations and enclosing a few of the recent editorial pages:

Now, I am still interested in having a piece under your byline on the editorial page, but in all candor, a little of the E. Pound orthography goes an awful long way … I am not much interested in DEEP articles on politics, religion, the Jews, the Communists, the state of the Middle East, etc., etc… . The hell with monetary policy. Write about poetry, or archaeology, or the people of Italy, or the state of American literary criticism; but if you are writing for my page, don’t write at the intellectual level of the Va. ¼ly Review. That is too high an octane rating for my readers.

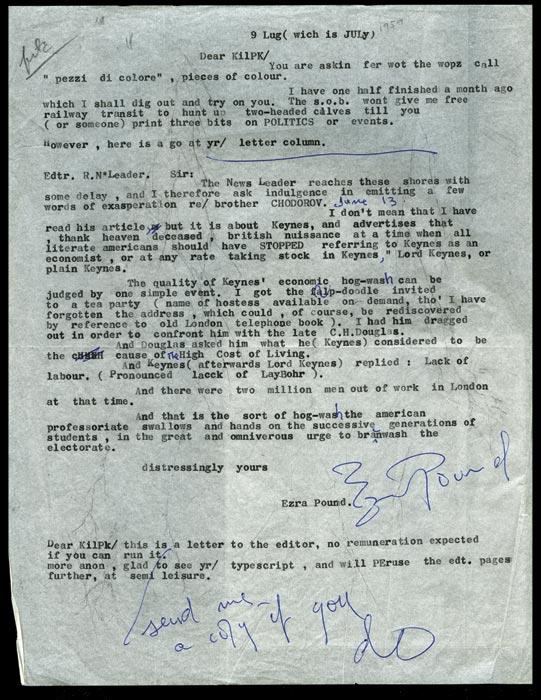

Pound’s final submission came a few days later and was dated July 9, 1959:

Dear KilPK/ You are askin fer wot the wopz call “pezzi di colore,” pices of colour. I have one half finished a month ago which I shall dig out and try on you. The s.o.b. won’t give me free railway transit to hunt up two-headed calves till you (or someone) print three bits on POLITICS or events. However, here is a go at yr/ letter column.

What followed was a letter to the editor regarding an article Pound hadn’t actually read, but apparently had heard made mention of John Maynard Keynes, an English economist he had despised since his early days in England. The letter was contemptuous—but relatively cogent. Kilpatrick ran it on July 14, 1959, and sent Pound a copy.

Scaling the editorial wall, however, seems to have diminished Pound’s interest in the News Leader. As the year wore on, his submissions to Kilpatrick all but ended. In February 1960, in one of his final letters to Meacham, Pound mentioned working on a brief piece for the News Leader. But he developed a urinary infection a few weeks later and was in and out of a hospital bed for the next three years. Kilpatrick never heard directly from Pound again. Two world wars, thirteen years of captivity, and a handful of nagging health problems had finally taken their toll on Pound. In 1960 he slipped into a period of silence that lasted until the end of his life. As a result, these letters, articles, campaigns, and rants—fragmentary and scattered though they may be—represent the last truly active year of Pound’s writing life. They reveal one of America’s most talented and innovative poetic minds in a last ditch effort to exert influence outside of literature.

The letters and articles by Ezra Pound published here are copyright ©2008 by Mary de Rachewiltz and Omar S. Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp., agents.