As we sped through the dusty heat of rural Somaliland on one of the region’s few paved roads, an armed escort behind us and the hills of Ethiopia ahead, Dr. Adan Abokor told me his story. Abokor is sixty-two years old with thinning, gray hair, and his steady, measured voice can mask his emotions, but his energy is undiminished, and his memories of 1982 are still raw. “I was a member of the Hargeisa Group,” he began. The now-famous organization of professionals started with the simple intent of improving schools and hospitals in the northwest region when the regime of General Mohamad Siyad Barre, then dictator-president of Somalia, showed little interest in developing the area. But as they held public meetings and launched a newspaper called Ufo—meaning “the wind before the storm”—the group became increasingly vocal in its criticism of the government’s neglect. Siyad Barre deemed their opposition seditious and ordered the Hargeisa Group leaders rounded up. Their incarceration was the spark for riots still remembered every February as the Day of Stone Throwing.

“Twenty of us were arrested,” Abokor continued. “We were tortured for four months then put on a show trial. Three of my friends were condemned to death, the rest to life imprisonment. After that the torture stopped,” he said, his speech flat and eyes fixed on the road, dead ahead. “We were kept in the prison in Hargeisa for eight months. Then, late one night, we were spirited away to Mogadishu and from there to another maximum security prison. I was in solitary confinement for the next seven years.”

Despite a life spent as a secularist in a Muslim country, in prison Abokor turned to God. He took to praying five times a day and reciting the Koran that each prisoner was issued. After a while the jail, guards allowed him one other book, so he chose Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. “It was the biggest book they had,” he told me.

Although the incarcerated members of the Hargeisa Group could not see or talk to one another they learned to communicate by knocking on the stone walls of their cells. “We developed a system, making an alphabet out of two different knocks, one with the knuckle of the middle finger, the other with the wrist,” he explained holding his right hand in front of his face, tapping at the air. “We started communicating normally, like a typewriter. It saved our lives.”

In the next cell, one of Abokor’s friends suffered from anxiety and panic attacks. He would wake in the night screaming. To calm him, Abokor began reading Anna Karenina, tapping out on the cell wall each letter of each word of the book’s eight hundred pages.

While Abokor and his Hargeisa Group colleagues sat jailed, a northern rebel army calling itself the Somali National Movement (SNM) began taking the fight against Siyad Barre out of the political arena and into the realm of war. When the northern rebels attacked two government garrisons in 1988, the shots they fired were among the first salvos in a civil war that continues in much of Somalia to this day.

Siyad Barre’s response was to carpet-bomb the northwestern city of Hargeisa, his fighter jets taking off from a military airstrip on the outskirts of town within view of the victims. Some estimates reckon that 90 percent of the city was flattened. Mass graves are still being uncovered, filled with the victims of the fighting—almost all from the northern Isaq clan. Women were raped, men were killed, children orphaned; crops were burned, livestock was slaughtered, wells were poisoned. One eyewitness, flying over Hargeisa soon after the war, described an empty roofless cityscape with gutted buildings “like empty swimming pools.”

“The President told us there was a war,” Abokor said, “that the cities we had known were now cities of ghosts, that our people were refugees. He told us it was our fault.” Throughout the bombings, Abokor continued to tap Tolstoy on his cell wall, to ease the fear and guilt he and his fellow prisoners felt. He had to bandage his bleeding hands, but still he knocked.

In 1989, as the Cold War thawed and the cracks in the Berlin Wall spread, the governments whose weapons and cash had kept Siyad Barre in place for twenty years turned their backs. Somalia’s murderously venal government was no longer needed by the West as a bulwark against Ethiopia’s Soviet-friendly regime so, at long last and too late for many, human rights became a higher priority. Mounting pressure from foreign governments—including the United States—led to Abokor’s release. But when he was freed, Abokor found his home city had been bombed to rubble, his father and older brother were dead, his relatives in exile.

Twenty years later the carpet-bombed city of Hargeisa has been rebuilt and is the peaceful—if cacophonous—capital of the self-declared independent Republic of Somaliland. Car engines and horns compete to drown out the call of the muezzin from the Grand Mosque; ambling pedestrians pay little heed to the battered vehicles that ply the dusty streets. Little wooden stalls sell all manner of imported Chinese and Saudi plastic goods. Bales of khat trucked in from the Ethiopian highlands are sold at miniature booths.

While Mogadishu is in the throes of an extremist Islamist insurgency and has become a virtual no-go zone for foreigners, Hargeisa is remarkably safe. I walked the hot sandblasted streets, bought ripe fruits from roadside stalls, sat beneath shady trees to drink camel milk tea and chat with locals, many of whom spoke English with an American twang, evidence of the number of Somalis who have lived, studied, and worked abroad. From the roof of the hotel, I watched the evening hustle and bustle as the heat of the day subsided and the city woke from its afternoon torpor. It certainly didn’t look like a breakaway region from a failed state.

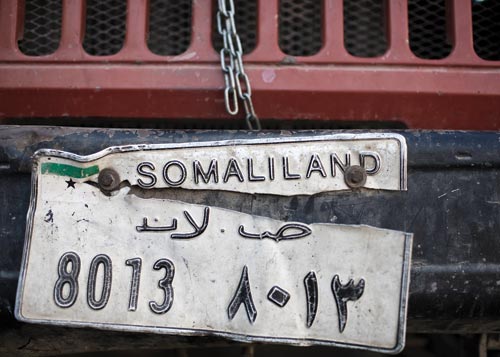

Somaliland has a defined—though contested—territory, an elected government that provides some services to its people, a civilian police force and professional army, its own currency and license plates. Its people have their own national identity: Somalilanders. But Somaliland is an invisible country, unrecognized by any other state in the world. According to international law, it does not exist. “Somaliland has everything but recognition; Somalia has nothing but recognition,” say observers. This, and the fact that Somaliland is more functional than the larger state of Somalia from which it is trying to wrench itself, marks Somaliland as unique among the world’s emerging nations.

Somalia today is a country in name only. Its besieged interim government, financed by the West and supported by the UN, controls only pockets of the wrecked seaside capital, Mogadishu. The government there is incapable of doing anything for its people. It fails to provide security, healthcare, employment, or education. Islamist insurgents battle the government’s forces and the 4,300 African Union peacekeepers that back them. Mayhem and death have been the norm since 1991 when Siyad Barre’s already failed state collapsed in a hail of gunfire.

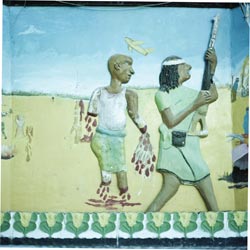

-

- Somaliland provides few diversions for young men, many of whom split their days between weight-lifting and chewing the mildly narcotic khat.

After more than seventy-five years of colonial rule, British Somaliland gained its independence on June 26, 1960—followed by Italian Somaliland five days later. In a rush of pan-Somali nationalist fervor, the former British Somaliland Protectorate, after just five days as an independent state, joined with the former Italian colony, and so the Republic of Somalia was born.

The dream was a Greater Somalia, a union of all ethnic Somalis across the Horn of Africa. The Somali people had been divided by colonialism’s arbitrary boundaries into five separate states run by different colonial masters: the French in Djibouti, the British in Somaliland and northern Kenya, the Italians in Somalia, and the Ethiopians in the Ogaden. Thus a blue flag of independence was raised in Mogadishu, the capital of the new Somali Republic, with a five-pointed white star at its center symbolizing the five fragments of the Somali nation and the desire that one day the nation would be whole again.

When that prospect quickly faded, clan elder and parliamentarian Hajji Abdi Warabe told me, Somaliland’s efforts to free itself from its bigger neighbor began almost at once. We met in a hotel garden in Hargeisa where Warabe had come for a breakfast of eggs and sweet tea made with camel milk. He was dressed like many older Somali men: in a short-sleeved shirt, a cotton sarong called a macawis, and leather sandals. He wore a white kufi Muslim hat perched on his head. His thick grey beard was stained red with henna, and gold teeth glinted from his heavy lower jaw. His hearing had begun to fail, but his voice and memory were strong. He recalled clearly those few days in June 1960 when Somaliland was an independent nation recognized by others.

“Somaliland was the first-born of all the Somali-speaking nations, the first to raise a flag,” he told me. “We took our flag to Mogadishu but when we entered that union we did not know what government was; we just knew what it was to be Somali. All we wanted was a Greater Somalia. We thought that if we joined the south the rest would join us.” But the dream of union never came close to being realized. A years-long guerrilla war fought in northern Kenya in the mid-1960s ended with the defeat of the Somali shifta, Somalis in Djibouti opted to stay under the wing of their French patrons, and a lost war in the late 1970s put an end to dreams of wresting control of the Ogaden region from Ethiopia.

So the Republic of Somalia searched for way forward on its own, but a dual and divergent colonial history in the republic that had formed—Italian on the one hand, British on the other—left behind clashing bureaucracies. Nothing worked together: the southerners ran their affairs in Italian, the northerners in English; law and accounting procedures varied as did taxes and currencies. Most of all the colonial legacies of the two regions were drastically different.

The Italian colonial project in Somalia was aimed at constructing another Italy in the Horn of Africa. A centralized state was imposed on what was an utterly decentralized society made up of nomadic camel herders. This meant “civilizing’” the pastoralists by breaking down “primitive” kinship ties and replacing traditional institutions with imported European ones. All of this subverted traditional society and alienated ordinary Somalis; they came to regard formal government as the workings of outsiders.

“We are quite different to those Somalis in the south,” Hajji Warabe explained. “Here the British did not interfere with our culture, they did not interfere with our religion. Our law and order that was in place when the colonizer came—of people listening to their elders, listening to their religious leaders—he did not tamper with that.” For the British Empire, Somaliland’s main function was as a source of livestock to supply its garrison in the Red Sea port of Aden. Beyond that there was little intervention. By early 1961, many in the northwest felt they had traded an absentee colonizer for a Somali dictatorship. Resentment grew as the northern Isaq clans dominant in Somaliland found themselves heavily outnumbered and marginalized by the southern Darod, Dir, Hawiye, and Rahanweyn clans, and the feeling was cemented when Siyad Barre led a military coup in 1969 and turned the state into a conduit for his own Darod clan’s advancement.

Northern grievances over the dysfunctional Somali state found powerful expression in the Hargeisa Group and the SNM rebel army, but they were both symptoms of a failed relationship, not the causes. The northern SNM rebels never marched on Mogadishu, five hundred miles to the south, but other insurgents backed by Ethiopia rose up against Siyad Barre, and by 1990, the president was disparaged as “Mayor of Mogadishu,” because his control extended no farther than the city limits.

In early 1991, a militia leader called Mohamed Farah Aideed, one of the leaders of the United Somali Congress, invaded Mogadishu with his army of gunmen perched on “technicals”—battlewagons fashioned from old 4x4 pickup trucks with heavy machine guns welded onto the flatbed. Aideed chased Siyad Barre out of town, but with the dictator gone the destruction only intensified. Aideed, and political entrepreneurs like him, dismembered and seized what remained of the state that Siyad Barre left behind. They converted the economy wholesale into a black market and backed their clan-based authority not with votes but with guns. The warlords were born and began to proliferate across southern Somalia.

Within two years, Aideed would become a household name in the US when his fighters shot down two Black Hawk helicopters and killed eighteen Army Rangers. The dead soldiers’ bodies were mutilated and dragged triumphantly through the streets of Mogadishu.

-

- Somaliland’s unofficial status makes it difficult for its government to receive aid for even basic services like schools or mental hospitals, where the patients are kept chained to their cots.

Anthropologists, such as Ioan Lewis in his seminal book A Pastoral Democracy, describe Somali culture as a segmentary lineage society with descent from shared ancestors traced through the male line. This form of social organization is well adapted to the harsh arid lands in which nomadic societies live, allowing different groups of different sizes to coalesce or disaggregate depending on the outside threats they face at that moment. Its brutally pragmatic logic of survival is explained by a local proverb: “Me, my brother, and my cousin against the stranger. Me and my brother against my cousin. Me against my brother.”

Aideed and his fellow Hawiye clan leader Ali Mahdi Mohamed, both of the United Somali Congress, joined forces to oust Siyad Barre’s Darod clan, the largest and most widely spread clan family in Somalia. But with the common enemy defeated, Hawiye solidarity evaporated: Aideed and Ali Mahdi turned their respective subclans—the Habr Gidir and Abgal—on one another in a battle for political power and economic control. But even in the midst of such chaos, when the US attacked General Aideed, the whole of Mogadishu turned against the American outsiders in a rare and violent expression of Somali solidarity. The years that have followed have been a violent dance of clans and sub-clans splitting and reforming, collaborating or fighting as circumstance shifted. Today in Mogadishu the fiercest fighting is again within the Hawiye clan between beleaguered president Sheikh Sharif Ahmed’s Abgals and Islamist insurgent leader Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys’s Habr Gidirs.

In the northwest, however, the SNM took advantage of the less divisive legacy of British colonialism in the region and allowed the dormant traditional mechanisms to resurface. Grassroots peace conferences were organized in communities across the territory. At these local conferences, people from all clans and sub-clans, and from both sides in the conflict, met to talk, resolve differences, and make decisions by consensus.

“From all over Somaliland we came to the town of Burao where we had a meeting bringing a thousand elders together,” Warabe told me, recalling the May 1991 Grand Conference of the Northern Peoples. “We agreed to form a government of our own under a flag of our own. We agreed to forget the past, forget all the bad things and start afresh. And we agreed to break away from our brothers in the south, wishing them good luck not bad. We used our old system—from before the British came—to reconcile. We said those who lost their fathers, their sons, we forgive each other. I myself lost five sons in the war, but I did not ask for compensation. We made an oath to become brothers again. We shook hands and began life again. That is how Somaliland stabilized.”

But Somaliland’s formation was more violent and contested than Warabe’s memory permits. For the first two years of newfound independence Somaliland teetered repeatedly on the brink of its own civil war. But in each case the conflicts were resolved through local peace conferences employing the traditional authority of the elders to reconcile warring parties. In 1993, as the interim government’s mandate reached an end and crisis loomed, a conference in the town of Borama was called to draft a national constitution and elect a new president. The draft constitution called for an executive president, a bicameral parliament, and an independent judiciary. Most significant was the establishment of an appointed upper house of clan elders known as the Guurti.

With this, Somaliland announced its intention to go its own way, shunning the Western model of a centralized nation-state by blending traditional clan-based authority with the beginnings of a limited modern democracy. In doing so the clan realities of Somali society were embraced rather than denied or ignored. As the anthropologist Lewis has written, “This arrangement reflected Somali political realities in a way and to an extent that had not previously been tried in the brief political history of Somalia with its Eurocentric political models.”

Somaliland offered then, and now, a new model for post-conflict nation building in Africa: one of local ownership and design. The strength of Somaliland’s homemade state was proven in 2001 when a referendum on the constitution was held. This was the first democratic vote in Somalia in over three decades, and the constitution was overwhelmingly endorsed. When President Mohamed Ibrahim Egal died suddenly in 2002 his vice president, Kahin, replaced him peacefully in accordance with the constitution. Kahin earned another five-year term after winning an extremely close election in 2003. A new election was scheduled for April 2008—but, so far, the people of Somaliland are still waiting.

-

- Many Somalilanders, like ten-year-old Mukhtar, still live pastoralist lifestyles, primarily raising and tending sheep, goats, and camels.

Musa Behe is a senior official in the opposition Kulmiye party (meaning “unity”) run by the veteran politician Ahmed Mohamed Silanyo. Party headquarters is a ramshackle collection of buildings down a bumpy dirt road close to the country’s National Electoral Commission. Behe sat in a boardroom where cream paint flaked off the walls and red net curtains billowed in the breeze. Before him on a wooden desk sat a vase of plastic pink roses. It was an incongruous setting for a former rebel commander who still sported the close-cropped hair and neatly clipped moustache of the disciplined military man.

Behe was remarkably candid about the kind of democracy that Somaliland is working towards, one that is Somali not Western. “The most important thing we have done since the war is managing to hold three elections in our country,” he began. “But sometimes, when I am alone, I doubt that we are really a mature multiparty democracy.

“It is alien to our culture; to me it is alien. What we are doing and what we are succeeding with is within our own culture. Even our parties, officially they are like yours, but they are totally different to yours,” he argued. “All the Somali political systems are tribally based so the party becomes bigger or smaller according to which tribal allegiances it gets. How the political leader utilizes or manipulates the tribal allegiances is the point of our politics. Some of our young people may ask, ‘What are you doing for me? What are your policies?’ but the majority just ask, ‘Who is the leader? Is he our tribe? We support him!’”

Another senior politician Faisal Ali Warabe, leader of the opposition Justice and Welfare Party, disagreed with the notion that Somaliland was already anything short of a mature democracy. “This is a multiparty democracy,” he said, “but because of our culture we cannot just implement everything that the West has done. We tried a multiparty system in the 1960s and instead of political parties we had tribal groups. They used to mushroom before the elections then die after them. Instead we have three institutionalised political parties that will last. So because of our traditions we have to have limitations to prevent parties purely based on tribe or region.”

This is pragmatism, but is it democracy? Perhaps not as the West might recognize it, but for Somaliland this limited democracy is working because it is rooted in the local context. As Dr. Mohamed Rashid Sheikh Hassan, a former BBC journalist-turned-opposition politician, put it to me, “Compared to Europe maybe we are not a true democracy but look at our neighboring countries: we are surrounded by Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, and Djibouti where there is no possibility of what we have here.”

But the whole system rests on free elections and is threatened by the ongoing delays. The stakes are high, Hassan told me—for Somaliland and for the international community.

“In the whole Horn of Africa we are the only viable, growing democracy.”

President Dahir Rayale Kahin sat at his shiny dark wooden desk, thick maroon curtains blocking out the sunlight. Before him stood a vase of plastic daffodils and a little globe; behind him was a vast oil portrait of himself. “The reason we search for recognition is not for prestige, it is a matter of survival,” explained the fifty-seven-year-old president. He feared seeing his aspiring country dragged into the abyss by Somalia, the world’s most notorious failed state. “The government in Mogadishu has been given carte blanche to be responsible for the whole of Somalia, but they are not even responsible for themselves. How can people who are not responsible for their own homes be the legitimate government?”

In every government ministry and on every street in Hargeisa, citizens express bitterness over Somaliland’s dearth of financial support—especially compared to the financial support Somalia receives. That sentiment is tempered by an understanding of isolation’s benefits: “From the beginning we were never interfered with by foreigners, whether Africans or Europeans, so from the beginning we saw our problems as our problems,” explained Kahin. “We saw it as our duty to solve our problems, but our brothers in Somalia are lacking that. Always they are waiting for foreigners to solve their problems. The international community pays money to everyone but gets nothing. Sometimes I tell them, ‘You are corrupting our brothers. Leave them alone. Let them sit together and solve their own problems.’”

The idea that a nationwide plebiscite might be held in Somalia is a sadly impossible dream, but in Somaliland it has been a reality twice already. In September, Somaliland was due to hold its third national elections, this time to choose a president. But the pre-election period was marred by delays, arguments, and incompetence. The presidential vote was already seventeen months overdue, severely damaging Somaliland’s reputation and leading to accusations that the president was clinging to power. More than once the country teetered on the brink of a constitutional crisis before pulling back. If done well the vote could have cemented the country’s reputation for democracy in the region and added weight to its argument for recognition from the international community.

The US and Britain pledged to provide $3 million towards the election and backed the troubled attempt to compile an accurate list of voters for the first time. This election was to be the first in the country’s history to use an electoral roll, but the registration exercise was so chaotic that the register had to be abandoned less than two months before the polls were supposed to open. Somaliland’s seven-strong National Electoral Commission is riven with partisan disagreements and widely viewed as incompetent. In Hargeisa, one exasperated political activist told me: “The voter register was supposed to prevent fraud, but the registration itself was fraudulent.”

Double and triple registration resulted in a register so bloated as to be unusable: in the last parliamentary election in 2005, 675,000 people voted, four years later and the NEC managed to register a scarcely believable 1.3 million voters, throwing the prospect of free and fair elections—and therefore Somaliland’s democracy—into doubt.

Abandoning the register in early August the government also threw out of the country a representative of Interpeace, a peace-building NGO tasked with advising and helping the Electoral Commission to do its job. The government blamed Interpeace for trying to undermine its election as it had refused to sign off on the disputed register. The two opposition parties then announced that they would boycott the campaign period and perhaps even the vote itself.

In his office a few months ahead of the scheduled date of the election, Kahin was emphatic: “As president of this country I am committed that this election will go ahead on 27th September, under any circumstances. That is my commitment. We will not continue to postpone the election anymore.”

Ultimately, in early September, the election was postponed again, and Kahin now says that the election will go forward in January 2010, at the earliest.

-

- Young men were brought to Burao from the countryside to register to vote and obtain a new Somaliland ID card.

Inside a stuffy office in the crumbling colonial relic that passes for his Foreign Ministry, minister Abdullahi Duale argues that the delays are tied to Somaliland’s unrecognized international status. Without recognition Somaliland cannot benefit from World Bank or International Monetary Fund support to fund projects like the Electoral Commission. The UN will not send election officials to help establish polling stations nor certify results.

This bind frustrates and angers the government. “We have got a legal case, a moral case, a historical case,” argued Duale. “We have a case that is worthy of recognition but thus far there hasn’t been one country that recognizes Somaliland!” he said, his upraised finger stabbing the air for emphasis.

The reason is simple—and sadly has nothing to do with the case Duale so tirelessly puts to the world. No non-African state is willing to recognize Somaliland until an African state does so for fear of being accused of neo-colonial meddling, and no African state will recognize Somaliland for fear of opening the Pandora’s box of encouraging its own separatists. Duale can shout his moral arguments till he is hoarse, but global realpolitik trumps principle every time. And, after 1993, the US seems to have little appetite for mustering support for peace efforts in the region. The bloody spectacle of dead Americans being dragged through Mogadishu changed US policy toward Somalia—and all of Africa—forever. The post-Mogadishu, no boots-on-the-ground approach to African conflicts, led the US to watch as Rwanda’s genocidaires hacked and shot their way through more than 800,000 victims in 1994 and as Sudan’s army and allied militias bombed and raped the people of Darfur.

When the US has intervened in Somalia since, it has been remotely, either by way of missile strikes or by proxy forces. By 2005, the US “war on terror” was in full flow and fearful CIA operatives spotted a growing Islamist movement in Somalia so they funded the clan warlords and their guns-for-hire to combat the Islamists. But the warlords lost, and for a brief few months in 2006, the Union of Islamic Courts held sway in Mogadishu, and a kind of peace and order returned, though not for long. The US backed Ethiopia to drive out the Islamic Courts, a group that was seen by State and Defense officials not as an indigenous source of law and order but, viewed through the single minded post-9/11 lens, an Islamist threat and potential al-Qaeda ally.

But, in time, remote and proxy attacks on Somalia may not be enough to ensure Somaliland’s nascent democracy. In October 2008, the violence convulsing the south came north to Hargeisa. Suicide bombings carried out by a cell of Somali Islamists destroyed a United Nations compound and the Ethiopian consulate, while a third attack reached inside the presidential compound, a squat white building protected by soldiers and slabs of concrete designed to slow approaching attackers.

These bombings left at least twenty-five dead and shook Somaliland’s delicate peace—instilling both a legitimate government fear that polling stations might be attacked by suicide bombers and providing a ready pretext for postponing elections and maintaining control of the country. Activists complain that the attacks have also given the government an excuse to roll back respect for human rights and crack down on dissent, but there have been no subsequent attacks and calm has returned. For the visitor to Somaliland the most visible legacy is the requirement to take a khaki-clad armed policeman with you when travelling outside the capital.

-

- After the al Shabaab suicide attacks in Hargeisa, the government assigned soldiers to guard voter registration stations.

Indeed, Somaliland argues its entitlement to support based on this hard-earned reputation for secular stability. In Somalia, pirates setting off from the coastal towns have disrupted one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, sending cargo prices skyrocketing and bringing in tens of millions of dollars in ransoms. But in Somaliland a functional, if shoestring, coast guard ensures the punishment of piracy. Three dozen prisoners have been captured, tried, and sentenced for piracy in recent months.

“We have fought terrorism, we have been the victims of terror, we have fought against piracy, in fact we have been the good guys in a very rough neighborhood,” Duale told me. “We are a very poor country operating in a very difficult environment. With the lack of recognition and the lack of engagement from the international financial institutions, we rely on our own resources, which means revenues of less than $50 million a year. It’s very rough and it’s really very tough.”

The country’s biggest principal export is livestock. Somaliland sends sheep and goats to Arab countries from the busy port at Berbera. Every day, creaky wooden galleons from Yemen and elsewhere in the Arabian peninsula unload pallets of fizzy drinks, crates of washing machines, sacks of grain, and cargo loads of 4x4 pickups. In short, Somaliland imports everything that it cannot produce itself—which means almost everything. Once empty, the ships fill up with livestock and head back across the Gulf of Aden. With an economy rooted in the pastoralist lives of its almost four million inhabitants, Somaliland struggles. There is a little commercial farming, a small scale and underexploited fishing industry, and the suggestion of mineral and oil deposits but not much else. Without international support, Duale warned, Somaliland’s progress might falter.

“Somaliland today is a de facto state: all we are lacking is recognition,” said Duale. “It is about time the international community brought Somaliland in from the cold.”

Tristan McConnell and Narayan Mahon traveled to Somaliland on a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Learn more about this project at pulitzercenter.org.