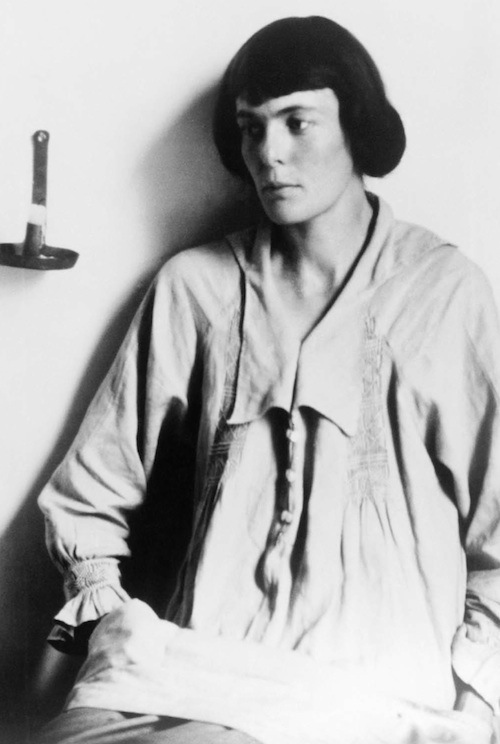

The anonymous collective wisdom of Wikipedia will tell you that H.D. is “an American poet, novelist and memoirist known for her association with the early 20th century avant-garde Imagist group of poets such as Ezra Pound and Richard Aldington.” She retains the aura of a Delphic priestess, a queer cultic charisma that appealed to waves of self-selected members of the elect—in the early years Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, Richard Aldington (her first husband), D. H. Lawrence; later such attendants as Norman Holmes Pearson; and still later, after her death, other scholars, often feminist, who brought her life and work back into focus in the 1970s and 1980s. And there is too an ongoing esoteric line of influence—transference? discipleship? inhabitation? telepathy?—that continues through poets’ transmissions and study, Robert Duncan’s H.D. Book and, in another key, Barbara Guest’s Herself Defined among the notable monuments of this line.

“Little, but all roses.” What the ancient poet Meleager said of Sappho, of the broken fragmentary inheritance she’d left. What H.D. echoes in The Wise Sappho (1919): “Little but all roses!” Confronted with 612 pages of poetry in the New Directions edition of H.D.: Collected Poems, 1912–1944, one might say, “Much, and only some roses.”

For surely as she was undervalued at various junctures of the past century, she has also been in some quarters indiscriminately praised. Out of some six hundred pages perhaps some fifty are dear to me; though I would recommend to anyone her World War II epic Trilogy, and reserve a special fondness for Helen in Egypt, a late work that restages in a Greek key aspects of her analysis with Freud, Theseus here playing the psychopomp to an unjustly reviled Helen.

While the later, longer, more discursive, mythico-narrative works are a certain achievement, and important documents of twentieth-century war writing and of the long poem, I am marking here what most marked me. It is no dispraise to be a poet best served by an anthology, a rigorously pruned selected—no dispraise particularly for this poet, who knew very well that “anthology” comes from the Greek: a gathering of flowers. “Little, but all roses.”

Some roses—from her first book Sea Garden (1916):

Rose, harsh rose,

marred and with stint of petals, meagre flower, thin …

(“Sea Rose”)

You are clear

O rose, cut in rock,

hard as the descent of hail.

(“Garden”)

and also poppies:

Amber husk

fluted with gold,

fruit on the sand

marked with a rich grain …

(“Sea Poppies”)

These early lyrics show one aspect of her characteristic best—they bespeak “H.D., Imagiste,” baptized thus by Pound, in a famous meeting in the tearoom of the British Museum in 1912. He had the manifesto-ing impulse, the impresario’s gift, and here—along with some few of his own poems, and Aldington’s, and eventually a few others’—here he found his exempla: here were poems sloughing off the slithering excesses of Georgian verse, the adjectival fripperies, the Latinate involutions, the flight from precision. Here, as in “Hermes of the Ways”—the poem that prompted Pound’s christening “H.D., Imagiste” and appeared in Harriet Monroe’s Poetry in 1913—one finds a version of what Pound called for, “An ‘Image’ … which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time” (“A Retrospect”). One finds a validation of his dicta:

1. Direct treatment of the “thing” whether subjective or objective.

2. To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of a metronome.

But H.D.’s poems, like Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro,” were never only exempla.

H.D. was extremely good, especially as a young poet, at generating objective correlatives for complex emotional states. Or rather, for a narrow band of emotional states—intense suspension, passionate rejection, inflamed supplication, ravaged and ravaging ambivalence, despondence, and, occasionally, ecstasy. Her first book, Sea Garden, is filled with successes in this line, her sea roses, sea lilies, and sea poppies all incarnating a complicated, paradoxically fierce delicacy, a kind of triumphant shattering, rent perfection—

Reed,

slashed and torn

………………………………

you are shattered

in the wind.

………………………………

Yet though the whole wind

slash at your bark,

you are lifted up …

(“Sea Lily”)

O wind, rend open the heat,

cut apart the heat,

rend it to tatters.

(“Garden”)

Her diction, her phrasing, her repertoire of images is willfully constricted, as if she had confined herself to one or two modes, Lydian, say, or Doric, sounding each tone and interval on a single-stringed instrument—

Can the spice-rose

drip such acrid fragrance

hardened in a leaf?

(“Sea Rose”)

Her gardens are violently agitated border zones, austere, wind-torn, and sea-lashed; they are not the hortus conclusus of Eden or pastoral, nor the scented gardens of Arabia or Jerusalem, nor the bowers of bliss of Italy transported to England.

honey is not more sweet

than the salt stretch of your beach.

(“The Shrine”)

Her Sea Garden is lit

by a desperate sun

that struggles through sea-mist.

(“Hermes of the Ways”)

By temperament and experience she was attuned to the Greek conviction that love was as much affliction as blessing—

Eros … bittersweet.

which Anne Carson has so brilliantly plumbed. Because she is so strongly associated with a subset of verse libre, of early-twentieth-century Anglophone free verse, her achievement as a rhymer and as a metrist is perhaps overlooked—for once you tune in, you cannot but hear her subtle yet obsessive rhyming,

is song’s gift best?

is love’s gift loveliest?

and you can’t but hear the intricate play of take, slake, break, and wake throughout her “Fragment Thirty-six,” or the resounding pyre of desire in “The Master”—

I did not know how to differentiate

between volcanic desire,

anemones like embers

and purple fire

of violets

—as she weighs the volcanic “red heat” of her desire for one love against the lure of the “cold / silver / of her feet”; and you cannot but hear in her well-judged repetitions, her identical rhymes (the zero degree of rhyme), how earned are these recurrences. They figure the intense, even obsessive attentiveness that is the hallmark of her best work—

what meadow yields

so fragrant a leaf

as your bright leaf?

(“Sea Poppies”)

Here and elsewhere she deploys repetition as much to dissociate as to emphasize: the terms of comparison widen as the word “leaf” recurs, the meadow leaf decisively distinguished from the hymned fragrant bright leaf of the “Sea Poppies.”

Nor can you not respond to her command of “intricate songs’ lost measure” (“Epitaph”). Through her study of Greek she found a way to give the heave to the pentameter (to paraphrase Pound), to approximate without strain the varied “dart and pulse” of Greek measures so long obscured by other treads.

She learned from Sappho and from the Greek tragedians; in Sappho she found not only lines, measures, situations, intensities, a whole erotic repertoire and key, but a deep-structural orientation to erotic triangles that resonated with her own—

Thus Sappho:

In my eyes he matches the gods, that man who

sits there facing you—any man whatever—

listening from close by to the sweetness of your

voice as you talk, the

sweetness of your laughter …

(“Fragment 31, ” Translated by Jim Powell)

and—

Thou flittest to Andromeda—

and thus H.D., bringing her bitter offering to Aphrodite—

I offer you this:

(grant only strength

that I withdraw not my gift),

I give you my praise and this:

the love of my lover

for his mistress.

(“Fragment Forty-one”)

Through Sappho she explored as well a kind of somatic poetics, a kind of sensually incarnational now—which underlies the seizure, the transport, of Sappho’s “Fragment 31,” when the beloved’s voice and appearance and laughter

sets the heart to shaking inside my breast, since

once I look at you for a moment, I can’t

speak any longer,

but my tongue breaks down, and then all at once a

subtle fire races inside my skin, my

eyes can’t see a thing and a whirring whistle

thrums at my hearing,

cold sweat covers me and a trembling takes

ahold of me all over: I’m greener than the

grass is and appear to myself to be little

short of dying …

(Translated by Jim Powell)

—and underlies H.D.’s development of “Fragment Thirty-six”:

I know not what to do:

strain upon strain,

sound surging upon sound

makes my brain blind …

—and underlies Sappho’s “Fragment 47”:

Eros shook my

mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees

(Translated by Anne Carson)

and underlies H.D.’s:

that will be me

to send a shudder through you,

cold wind

through an aspen tree

(“Sigil”)

For all her capacity for swoon there is also the tough slap, the sharp turn, the riposte, the counterpunch, the hard swerve—

I could scrape the colour

from the petals

like spilt dye from a rock.

(“Garden”)

I envy you your chance of death,

how I envy you this.

(“Fragment Sixty-eight”)

spare us the beauty

of fruit-trees.

(“Orchard”)

Amid the sculpted intensities, the sounded-out extremities, we find too the salutary disgust with beauty, with the pretty, the lovely, the merely ornamental. The taut early work is ascetic, purged.

O for some sharp swish of a branch—

there is no scent of resin

in this place,

no taste of bark, of coarse weeds,

aromatic, astringent—

only border on border of scented pinks.

………………………………………………………

For this beauty,

beauty without strength,

chokes out life.

I want wind to break,

scatter these pink-stalks,

snap off their spiced heads,

fling them about with dead leaves …

(“Sheltered Garden”)

Here is a poet whose narrow yet prodigious strengths run perilously close to her weaknesses. A poet of passionate intensity, she must rely on a perfect pitch. When there is strain in her work, she runs the risk of a false or willed swooning, a mandated abjection. Yet among the states she is so brilliant at evoking is the transfig- ured and transfiguring abjection of the lover. That this posture is all too familiar for women makes for some uncomfortable reading—not because women should not explore erotic abjection but because its rendering can become quite predict- ably banal. One can of course find many examples of a kindred overreaching and emphatic swooning in the work of male poets, viz. Shelley: “I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!” (“Ode to the West Wind”); “I pant, I sink, I tremble, I expire!” (“Epipsychidion”). And Keats is notoriously full of bathetic heroes and overgilded lilies. Here one walks on very interesting terrain, the terrain of mastery and power. For no real poet, no serious reader, does not respect mastery and power; the ques- tion is, what kind of mastery, what power?

Consider a poem whose vocation in print began in 1914, “Oread”:

Whirl up sea—

whirl your pointed pines, splash your great pines

on our rocks,

hurl your green over us,

cover us with your pools of fir.

An apparently slight poem but a world-brightening poem, a poem of immediate mythic authority and vocal power, H.D.’s Oread, her mountain nymph, here apostrophizes the sea, as so many of her human brethren have—that sea “cold dark deep and absolutely clear,” as Elizabeth Bishop wrote, “element bearable to no mortal.”

A long tradition holds that poetry is, if not thinking per se, close to, kindred to, thought: as Heidegger observed in “The Thinker as Poet” (1947), “Singing and thinking are the stems neighbor to poetry.” And Hannah Arendt in her book The Human Condition specifically remarked the proximity of poetry to “the thought that inspired it”: “Poetry, whose material is language, is perhaps the most human and least worldly of the arts, the one in which the end product remains closest to the thought that inspired it.” And Arendt further observed, “Of all things of thought, poetry is closest to thought, and a poem is less a thing than any other work of art.”

So a poem, “less a thing than any other work of art,” is yet a “thing of thought.” Whirl up sea. Whirl your pointed pines. Splash your great pines on our rocks. The lure of the barely yet decisively reified thing, the hardly rendered poetic “thing of thought,” the only-just-artifactualized voice: this is one appeal of the Oread’s call. Over the years I have found myself often drawn to poems that project themselves forth less as monument than as song or spell, less as artifact than as enunciation. Or rather I oscillate, fascinated, between what I think of as two poles marking the limits of a highly variegated poetic spectrum.

H.D.’s “Oread” versus, or alongside, Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium.” Or James Schuyler’s apparently casual watercolors against, or alongside, Frank Bidart’s awesomely wrought “The Second Hour of the Night.”

H.D.’s “Oread” has seemingly barely made it over the threshold of artifactualization though it is decisively enunciated. The poem bespeaks the logic of artifactualizing thought: the poem appears as if from an archaic world of ritual incantation, a fragment of our mythic inheritance, in which to speak was to command the elements.

Splash your great pines on our rocks. Cover us with your pools of fir.

Nietzsche suggested and Derrida after him that behind every thought, within every concept, lies a figure, a trope: “Abstract notions always conceal a sensible [sensory] figure,” Derrida observed in the “Exergue” to White Mythology. Turning from philosophy to poetry, Paul De Man was happy to follow Nietzsche down this sublimely figurative road in his essay “Anthropomorphism and Trope in Lyric.” More recently, in Poetry and the Fate of the Senses, Susan Stewart has illuminated the profoundly anthropomorphic wagers of lyric. Invoking Vico’s account of “poiesis as a process of anthropomorphization,” she writes, “Vico explains that the imagination stems from bodily or ‘corporeal senses’ and is moved to represent itself by anthropomorphizing nature and by giving being to inanimate things.” Stewart further suggests that “only when poetic metaphors make available to others the experience of the corporeal senses can the corporeal senses truly appear as integral experiences. The self … is compelled to make forms—including the forms of persons striving to represent their corporeal imaginations to others.”

Whether thought has an ultimately and exclusively linguistic basis, whether language itself is primarily figurative, whether all language is, as Emerson claimed, fossil poetry, whether there is such a thing as “thinking in images” as opposed to “thinking in language,” these fine-grained philosophical and linguistic and neurological arguments I will leave to those so much more expertly informed. Whether the limits of my language are indeed the limits of my world I cannot prove; the limits of language do seem provisionally to set the outer reaches, however, of a poem’s call to me and perhaps to you.

If a lion could speak, we would not understand him. So wrote Wittgenstein, famously, in his Philosophical Investigations.

I cannot help but recall his gnomic pronouncement when I recall H.D.’s “Oread”: if a mountain nymph could speak, would we understand her?

Whirl up sea—

whirl your pointed pines …

H.D.’s “Oread” displays and transforms the anthropomorphic, animating premise of apostrophe, that gesture so basic to lyric. (Viz. Shelley, in his “Ode to the West Wind”: “Be thou me, Spirit fierce, my Spirit!”)

The Oread is nymphomorphic, her subjectivity projected from and grounded in her mountain ground, its pine trees, its sensuous greens and stark rocks. Thus when she addresses the sea, commands the sea, provokes the sea to respond to her spell, she cannot help but invest the sea with her mountainous mind:

splash your great pines

on our rocks,

hurl your green over us,

cover us with your pools of fir.

Cover us with your pools of fir, your aqueous splash gone spiny, piney, and green.

H.D.’s incantation both displays and thwarts the standard anthropomorphic logic of projection basic to lyric and perhaps to human thinking; the poem may also be read as a brilliant anatomy of what Freud called “the omnipotence of thoughts.” The fantasy that one’s mind not only can do work in the world but indeed can animate the world—the animistic and fetishistic conviction that objects or natural elements are alive—this is the condition common to very young children and primitives, Freud argues, and of course, common to those who persist in the childish pursuit of art making.

And yet. And yet. As Susan Stewart observes and as Elaine Scarry so lovingly, carefully shows in The Body in Pain, we spend our lives relying on the near-aliveness of nature and of the object world, taking for granted, when privileged, when secure, that the object world, which includes poems as much as tools or tables or computers, responsively answers to and as if by magic anticipates human needs, human desires. Any artifact, and any humanly prepared or transformed substance, bears within it not only the congealed labor Marx reminds us it does or the movement of thought Arendt tells us it does but also a more generalized human well-wishing: Be well. Sit in this chair. This chair knows and anticipates both the human need for rest and the contours of a resting human body. Now shut the window. This window bespeaks and answers the simultaneous desire for shelter and our love of light and a view. Now read this poem. This poem bespeaks our desire to commune, to hear and be heard, to make the chaos of inner feeling not only sentient but sharable.

This poem brings the murk of inner corporeal urgencies into enunciation, as Susan Stewart might put it. If a mountain nymph is a creature of fantasy, her imagined subjectivity is no less compellingly spoken, brilliantly and economically thought, for that. A stranger may address us across centuries, languages, countries, genders. An object, an artifact, addresses us. We lend and are lent a voice, a form. We may be addressed across species. A sympathetic cognitive projection underlies the logic of address here—

Hurl your green over us—

and enacts that broader linguistic, discursive condition of intersubjectivity about which Emile Benveniste wrote so illuminatingly years ago in his essay “Subjectivity in Language” (1958): Regarding the reciprocal structure of personal pronouns, “I” and “you,” Benveniste observed, “This polarity of persons is the fundamental condition in language, of which the process of communication, in which we share, is only a mere pragmatic consequence … The very terms we are using here, I and you, are not to be taken as figures but as linguistic forms indicating ‘person.’ It is a remarkable fact—but who would notice it, since it is so familiar?—that the ‘personal pronouns’ are never missing from among the signs of a language, no matter what its type, epoch, or region may be. A language without expression of person cannot be imagined.”

I may be a mountain nymph. You may be the sea. To command you, to address you, I must think you. “I” must think “you.” And yet even as I think you I interfuse you with my own nature—my pines, my fir, my rocks.

Or rather, “our rocks.” Splash your great pines on our rocks. For another thing H.D.’s Oread suggests in her vocal gesture is that hers is a communally grounded subjectivity—she speaks for and from a collective mode of social being. We might say that in Marxian terms she summons the sea as a species being, as a mountain nymph speaking herself as a nymph among nymphs, one of a species of nymphs with similarly mountainous minds and desires for sea-brought inundation: Hurl your green over us. Cover us with your pools of fir.

Thus through a fictive creature, the problem and fact of shared and sharable sentience sings itself forth. The Oread does not “sing beyond the genius of the sea,” as Wallace Stevens’s singer does in his “Idea of Order at Key West”: her utterance aspires precisely to sing the very particular genius of the sea—its capacity to respond, to whirl, splash, hurl, and cover, to inundate on command. Whether this is an invocation on the border of a desired annihilation, whether this is an incantation portending a violent lashing cleansing, we do not know. We might speculate that the Oread, here speaking for and implicitly with her sisters, calls on the sea to save-by-covering: according to legend, one Oread, Britomartis, threw herself into the sea to escape one of the predatory pursuers that perpetually trouble nymphs. Perhaps, we might speculate further, perhaps “Oread” might be read as a ritual re-enactment of that supplication, a remembering of that beneficent covering, that cloaking of the vulnerable subject in the medium of its choosing: Cover us with your pools of fir. We might recall too that Echo was an Oread, and might consider that H.D.’s “Oread” is a complex echoing of a primary mythico-lyric call. And here too we might recall Benveniste on personal pronouns, their logic of echo: “I posits another person, the one who … becomes my echo to whom I say you and says you to me.” The Oread is also an Auread, a hearing, a sympathetic responding to the sea, which precedes, as it were, the call. Here myth finds its “muthos,” its saying. Here we might again invoke Wallace Stevens for a gloss on “Oread,” for as Stevens wrote: “A mythology reflects its region … This raises the question of the image’s truth. / The image must be of the nature of its creator” (“A Mythology Reflects its Region”). Here, I would argue, H.D. has thought the preconditions of mythic saying and mythic imaging.

This may seem a lot of weight for an imagist poem to bear—though whether “Oread” truly is or remains an “imagist” or “vorticist” poem, as Pound first framed it, is interestingly arguable. There are of course many ways poems think about thinking, or about not-thinking. “Oread” presents a nondiscursive, phenomenologically oriented speech act. As a poem, it is barely, and yet decisively, there.

Stevens’s “Man with the Blue Guitar” helps me think further about “the nature of the creator,” this aspect of “Oread”:

XXXVIII

I am a native in this world

And think in it as a native thinks,

Gesu, not native of a mind

Thinking the thoughts I call my own,

Native, native in the world

And like a native think in it.

Like a native, H.D.’s Oread thinks. Like an Oread, a native of the mountain, the Oread is native in the world and like a native thinks in it.

This returns us to the remarkable capacity of lyric projection, its positing of nonhuman or marginally human natives who nevertheless might think as natives in our shared world. This can become an ethico-lyrical project, perhaps best exemplified for me in Wordsworth’s early work, his powerful investigations in Lyrical Ballads of the thought of children, “idiots,” vagrants, rustics, Native Americans, his sympathetic enactments of their thought over and against Coleridge’s conviction that rustics, for example, didn’t quite think. The most spectacular case of the sympathetic projection of thought may arise in Wordsworth’s “Hart-Leap Well,” a long ballad that begins as a conventional neomedievalizing chase, a story of one Sir Walter who hunts a hart and marvels at the hart’s final leaps to its death: on that spot Sir Walter pledges to build a pleasure dome, a retreat for enjoyment and remembrance—not to recompense or memorialize the hart but to commemorate Sir Walter’s savoring of its glorious leaps en route to its death. In contrast to Sir Walter’s pleasure in the kill, we encounter in part II a typical Wordsworthian interlocutor, a shepherd who retells this story as the legendary lore, the backstory as it were, of this haunted place:

Some say that here a murder has been done,

And blood cries out for blood: but for my part,

I’ve guessed, when I’ve been sitting in the sun,

That it was all for that unhappy Hart.

What thoughts must through the creature’s brain have pass’d!

From the stone on the summit of the steep

Are but three bounds, and look, Sir, at this last!

O Master! it has been a cruel leap.

(“Hart-Leap Well,” ll. 137–44)

Remarkable here is not just the sympathy extended to a fellow creature in pain, a creature reimagined across centuries as exhausted and about to die, but the projection of thoughts into that creature’s brain: What thoughts must through the creature’s brain have passed! Here poetry announces that shared sentience, not the fact of shared language, will be the grounds of notionally shared thought. That the hart thought, the shepherd does not doubt; what specifically the hart thought, he cannot say: If a hart could speak, we would not understand him. Yet the broad contours of the hart’s thought we can guess at, Wordsworth’s shepherd suggests. We understand the hart’s thought without the medium of language.

Haunted by a thinking hart, Wordsworth calls for the development of thinking human hearts, and in this ballad as in so many others he conducts an experiment in the nature of thought, its reach, its limitations. Again, what intrigues me about Wordsworth’s hart, and H.D.’s Oread, is that while they are obviously generated out of the anthropomorphic logic of poeisis—their sensuous, sentient human makers have clearly, humanly, made them—they nevertheless partly resist that logic. “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord” (Isaiah 55:8).

H.D.’s Oread and Wordsworth’s hart and Margaret Cavendish’s horribly hounded hare, poor Wat—all speaking or figured on the verge, their sentience on the edge of extinction—for me these figures are connate with the first “susceptible being” Wallace Stevens conjures in his poem “A Discovery of Thought” (1950), itself a poem of first lights, first sights, first thoughts, and first words:

One thinks, when the houses of New England catch the first sun,

The first word would be of the susceptible being arrived,

The immaculate disclosure of the secret no more obscured,

The sprawling of winter might suddenly stand erect,

Pronouncing its new life and ours, not autumn’s prodigal returned,

But an antipodal, far-fetched creature, worthy of birth,

The true tone of the metal of winter in what it says:

The accent of deviation in the living thing That is its life preserved, the effort to be born Surviving being born, the event of life. The susceptible being arrived, a far-fetched creature, speaking in its own accent of deviation: this is one way to hear H.D.’s “Oread”—

And those who have ears to hear will hear.

This is the sort of thing H.D. herself thought, as attested in one of her rare prose works on poetics: “Notes on Thought and Vision” (1919). She was hieratic, an elitist of the soul, though she had a democratic strain as well: “Anyone who wants can get through these stages today just as easily as the Eleusinian candidates outside Athens in the fifth century, B.C.” (Just as easily!) Her notes on visionary initiation are occasionally slightly repulsive: “If your brain cannot stand the strain of following out these lines of thought, scientifically, and if you are not balanced and sane enough to grasp these things with a certain amount of detachment, you are obviously not ready for experiments in over-mind consciousness.”

Well then!

And she invokes Socrates: “Today there are many wand-bearers but few inspired.”

She was, she is, not wrong.

In the mid-1990s I would sometimes attend a University of Chicago colloquium on modernism. I thought of its very learned, very serious, very intense members as “the bearded male modernists,” though only some had beards, and only some were male. On one occasion we were to discuss Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan” alongside H.D.’s “Leda,” with some recent critical essays as well. What I recall from that two-hour session, the last I attended, was a creeping feeling of horror, as it became clear that, whatever the intent of the programmers, the evening was devolving into a “who does rape better” discussion: and clearly, Yeats did rape better.

Touché!

It is hard for me these years later to disentangle my strong sense of the bad faith of the terms of that discussion from any reading of these poems. Obviously, one might say, obviously Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan” is a better poem—if by “better” you mean memorable, wrought, impressive, titanic, influential, dialectical, linguistically and rhythmically virtuosic. And one could also shift the terrain here and say that whereas Yeats is wringing out of myth (and into myth) a world-historical shattering sonnet, H.D. is up to something else—tracking the phenomenology of a kind of benumbed erotic encounter, one that seems almost not to have happened:

Where the slow river

meets the tide,

a red swan lifts red wings

and darker beak,

and underneath the purple down of his soft breast

uncurls his coral feet …

Ah kingly kiss—

no more regret

nor old deep memories

to mar the bliss;

where the low sedge is thick, the gold day-lily

outspreads and rests beneath soft fluttering

of red swan wings

and the warm quivering

of the red swan’s breast.

One registers aspects of her typical lyric style: its hypnagogic state; the carefully paced phrasings, the predominance of slow, heavy monosyllables, the insinuating rhymes (kiss/bliss, rests/breast, wings/quivering); the stationing of the poem at a border territory “where the slow river / meets the tide,” the meeting here slow, aqueous, and obliviating—the kiss negating or surpassing “regret” and “old deep memories”; the action muted, literally and figuratively submerged, the strongest verbal forms the gerunds “fluttering” and “quivering”—“quivering” a recurring word in H.D.’s erotic lexicon (as in “the passion / quivering yet to break” in her “Fragment Thirty-six”).

As I recall, the charge against H.D.—and it was also of course the charge against the scholars who had worked hard to rehabilitate her reputation, in the by-now familiar yet no less praiseworthy terms of feminist recuperation—included this: her evasion of real stuff, of history, violence, difficulty, the world: her evasion of everything Pound, for example, embraced. (That this was a comparison that for some would tip the scales for H.D. did not occur to this crew.) She did not put on his knowledge with his power. Condescension would morph quickly into contempt for the woman who let her wealthy lesbian lover support her, the woman who founded no movements, who edited no journals, who apparently lazily glided around Europe entre les deux guerres in a twee supine daze, her only claim to fame her association with More Important (or rather Actually Important) Artists and perhaps her later, brief analysis with Freud.

It is interesting how often one is expected to be for something and simultaneously against something else. The both-and falls away, so too the neither-nor.

My mind is divided;

I know not what to do.

(Sappho)

Neither honey nor bee for me.

(Sappho)

And it is true that H.D. swims in some murky waters, and that after the first toughened hard-soft, sweet-bitter Imagist lyrics her poems are often slack—and it is true that, as my love said upon reading H.D.’s “Leda,” one might well re- spond, “Well, isn’t it slightly ridiculous?—‘Ah kingly kiss’??!”

And one could say as well that it is all too typical of her verse to collapse into a kind of postcoital inertia, nothing to mar the bliss, no blow or burst of thought or rhythm to interrupt the warm quivering / of the red swan’s breast.

All this could be said.

And also: Whirl up sea!

And also: Heu, it whips round my ankles!

Much of the force of great modernist works arises from their desublimating impulse channeled into shatteringly, newly adequate forms—their fuck you, here it is, take it for all in all, we shall not be constrained by gentility, there will be swagger sex and frying liver and shitting and ads and trams and masturbating and shell shock and newspaper datelines and porous consciousness and airplanes and abortions and cross-dressers and drumming Negroes and tragic Sapphic liaisons, etc.—

H.D. thought D. H. Lawrence’s later poems not sublimated enough. She rejected them entirely. One might find a poem like “Leda” entirely too sublimated. More broadly, her mythic toolkit, her cultural surfing moving ever to the fore in the later work, is for some readers an impediment—what is all this Egyptian stuff, not to mention the ongoing repertoire of Greek figures, masks, and plots: Why not say what happened? as Robert Lowell came to ask.

This perhaps marks an impoverished sense of “what happens.”

Where H.D. is like Yeats for me, is like my memory of the first impact of Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill” on me, is like Donne’s “Batter My Heart” for me, is like certain mauReen n. mclane 45 stanzas and lyrics in Shelley for me, is like Sappho, is indeed often My Sappho, is in her bodily force—her kinesthetics of transmission—for some of her poems bypassed my brain and registered directly on the nerve endings.

All these poets have had for me a distinctly somatic power.

One could say they cast a spell—albeit different spells.

Thus

though I sang in my chains like the sea—

there was a ringing

up so many floating bells down

and I wondered

what had that flower to do with being white?

and trembled, for

what but design of darkness to appall

if design govern in a thing so small

and found myself

turning and turning in the widening gyre

and knew

my mind is reft

and said

my soul is an enchanted boat

born on the silver waves of thy sweet singing

and faltered as

strain upon strain,

sound surging upon sound

makes my brain blind

and I found myself

nor ever chaste except you ravish me—

I sat on a narrow bed in an English house I read in a large book and found sound surging upon sound / making my brain blind—

O I am eager for you!

To talk about H.D. is almost inevitably to talk about sexuality—not least because she so often invites it, particularly in the poems titled after Sapphic fragments. To adopt Sappho’s mask is to invite the sexual inquiry that Sappho’s name itself marks. “Sappho has become for us a name, an abstraction as well as a pseudonym” (H.D., The Wise Sappho).

My Sappho begins with H.D. Or perhaps my Sappho begins with Pound:

Spring …

Too long …

Gongyla …

(“Lustra”)

A ring of girls dancing, a chorus—what Sappho legendarily led. I do not have a beautiful little girl I did not have a strange vision of picture-writing in 1919 while at the Scilly Isles with my lover I did not survive influenza and give birth and outlive the wreck of my marriage and the Great War and live to write a long epic in another war—

H.D. did.

To think about H.D. is to think, eventually, about Freud. For theirs was a conjunction.

“She is perfect … only she has lost her spear.”—what Freud, “the Master,” says to H.D., as she recalls it in Tribute to Freud. It is 1933 and she has come to Vienna to study with the great old god, the founder of a new religion, the braver of mysteries: Freud. They share a deep love of antiquity; he knows archaic Greece to be her imaginative homeland. He has shown her a small figure, a statue of Nike—one of the many ancient treasures and fragments adorning his office.

She is perfect, only she has lost her spear.

A rather leaden point, this, if we choose to take it a certain way (and H.D. did)—the goddess, and the woman poet, missing (lacking) the phallus.

To talk about poetry is for some to talk about therapy and psychoanalysis. Perhaps it stinks of the twentieth century, this enmeshing of poetry and psychoanalysis, or of poetry and the psychotherapeutic.

When I was in therapy I sometimes talked about what I was reading, what I was writing, and it was natural that I should mention H.D. and the long essay I was then writing on the relationship of H.D. and Freud, and more broadly on that between poetics and psychoanalysis.

“Put H.D. in the place of Sigmund Freud” (Tribute to Freud).

As the analysts tell you, as Freud told H.D., there are always multiple causes for any one thing—events are “overdetermined.” And there are no accidents.

So it was no accident that I was fixated on this relationship as—

I did not know how to differentiate

between volcanic desire,

anemones like embers

and purple fire

of violets

like red heat,

and the cold

silver

of her feet:

I had two loves separate;

God who loves all mountains,

alone knew why

and understood …

(“The Master”)

as I was riven—

I know not what to do,

my mind is reft:

as I had lain in a bed wondering—

Shall I break your rest,

devouring, eager? …

Shall I turn and take

comfortless snow within my arms?

press lips to lips

that answer not,

press lips to flesh

that shudders not nor breaks?

as I would later lie in a bed next to the beloved, incandescent, indecisive—

I know not what to do:

strain upon strain,

sound surging upon sound

makes my brain blind;

as a wave-line may wait to fall

yet (waiting for its falling)

still the wind may take

from off its crest,

white flake on flake of foam,

that rises,

seeming to dart and pulse

and rend the light,

so my mind hesitates

above the passion

quivering yet to break,

so my mind hesitates

above my mind,

listening to song’s delight.

as earlier in a rented room in Washington, DC, I had lain anguished awake next to my husband, who also lay there anguished awake—

I was not dull and dead when I fell

back on our couch at night.

I was not indifferent when I turned

and lay quiet.

I was not dead in my sleep.

(“Fragment Forty-one”)

And when my husband’s brother said to me in a dark bar one night, “So it’s the bisexual thing that’s the reason for the divorce—?” and the bones of my face turned to ash—

Could I not have said—

I have had enough—

………………………………

O to blot out this garden

to forget, to find a new beauty

in some terrible

wind-tortured place.

(“Sheltered Garden”)

Might I have said—

Splintered the crystal of identity,

shattered the vessel of integrity …

(“The Walls Do Not Fall”)

Could I have thought—

I compensate my soul

with a new role

(“Sigil”)

Did I really feel—

This is my own world,

these can’t see …

(“Sigil”)

Could I have predicted—

That will be me,

silver

and wild and free;

that will be me

to send a shudder through you,

cold wind

through an aspen tree

(“Sigil”)

I have thought of her in a bedsit in England, in a studio in Chicago, in a cabin in New Hampshire; I have thought of her by seashores, by lakes, and inland; I may think of her in future years when I discover what sears and what wanes in places I cannot yet know—

no motion has she now, nor force, yet she has motion and force; she is of the rocks and stones and trees; she is of the sung mind—

Let us bring her an offering, let us

dare more than the singer

offering her lute,

the girl her stained veils,

the woman her swathes of birth …

(“Fragment Forty-one”)

Let us say that like Sappho, H.D. “has become for us a name, an abstraction as well as a pseudonym for poignant human feeling, she is indeed rocks set in a blue sea, she is the sea itself, breaking and tortured and torturing, but never broken” (The Wise Sappho)

Let us say

we have a song,

on the bank we share our arrows;

O let us say then—

She is great,

we measure her by the pine trees.

(“Moonrise”)