Every advance that the Latin American peoples have made in the way of civilization, every improvement in their social organization, education of the masses, distribution of wealth or political reform, has been at the cost of the rebellious people, and the leader, the rebel, has always been sacrificed in the struggle, fallen in the battlefield or murdered by the reactionaries. —José Clemente Orozco

Brad Will always turned up where things were happening. Even to write that in the past tense seems strange, almost laughable, and nobody would laugh about it more than he would, with his conspiratorial raised-eyebrow chuckle, a laugh that let you in on a secret joke. To write it in the past tense negates the immortality that we often felt around each other. But he’s dead now, and so I have to write it that way, because it seems the only way to believe it enough so as to set some part of his story down. I still half-expect him to come rolling around the corner on his bike, dirty from traveling, eating a dumpster-dived bagel while gesticulating theatrically, recounting his latest adventures in Brazil or the South Bronx.

In a decade of living in New York City, time and again I would run into Brad in the middle of the action, whatever that action happened to be: a street protest at the Republican National Convention, a guerrilla dance party on the subway, a crowd of thousands fleeing the collapse of the Twin Towers. I once saw him, while being chased by the police among hundreds of bicyclists on a protest ride through Times Square, shoulder his bicycle and run right over the top of a taxi to freedom. He always gravitated toward the conflict and conflagration, loved getting close enough to touch before leaping back. He was fearless, and he usually got away with it, coming back with stories of how the cops were just inches from grabbing him, how the railroad bull walked right by his hiding place without spotting him. And later, as he went further, to countries where tectonic social conflicts rumbled just below the surface, drawn by that same impulse, some junk-craving of conscience and adrenaline, he spoke of how the bullets whizzed by without hitting him.

So when a friend of ours called me one morning in late October 2006, her voice cracking in that tone that conveys the worst news: it’s Brad … I already knew, but still didn’t believe. Everything else was mere detail, whens and wheres, unmoored fragments of fact: Oaxaca. Filming a street demonstration during the teachers’ strike down there. Twice in the chest. Never made it to the hospital.

He filmed his own assassination.

What ineluctable calling had drawn him down there, to someone else’s war in Oaxaca, and ultimately to his own death? The why was left, as it always is, to the living.

Brad’s unedited footage was posted within a day to YouTube, that online forum for cat antics, bicycle tricks gone awry, and now postmodern martyrdom. Handheld and shaky, shot from a first-person perspective, it stops and starts at random, a pixilated, low-resolution window into Brad’s last day on earth, unfolding with the inevitability and logic of a dream.

A brilliant morning on the outskirts of Oaxaca, white tropical daylight that shocks a camera’s sensors into overload, washes out colors, makes shadows absolute. A blue municipal bus blocks an intersection. We peer over the shoulder of a young man in a sleeveless shirt, face hidden behind a bandanna, a length of pipe in his hand. A chattering crowd gathers, a woman yells, “¡Compañeros, vámonos!”

Brad had grown up comfortably in a wealthy Chicago suburb, went on family vacations skiing in Aspen, and attended an expensive private college, but always chafed against his origins. He had come to New York in 1995 and moved into a squatted tenement on Fifth Street in the East Village. The neighborhood was still suffering the blight of the fiscal crisis and white flight of the 1970s, and was dotted with dozens of squatted buildings and vacant lots that had been converted into community gardens. It would be easy to dismiss this foray as an upper-middle-class kid’s slumming, but squatting was no mere segue before he assumed the mantle of his class and got an MBA and a BMW. He threw himself into that world with all his energy and imagination. Brad loved the idea of reclaiming land and buildings that had been essentially left to rot by the city, but he had arrived, along with Mayor Giuliani, just as New York was shaking off years of neglect: crime was dropping, property values were rising, and the days when space in the city was free for the taking were coming to an end.

A fire at the squat (caused ironically by Brad’s own space heater), served as a pretext for the city to condemn the building, and in short order a wrecking crane came in to demolish it. A crowd had gathered on the block, and someone filmed with an 8mm camera. In the grainy footage, just as the crane began smashing into the building, a hooded figure emerged on the roof—Brad, of course, raising his hands in a classically New York show of defiance, like Ratso Rizzo pounding the hood of a taxi in a crosswalk. The gesture, iconically rebellious and more than a little crazy, did nothing to stop the demolition of the Fifth Street squat, or to stem the tide of gentrification that lapped, one letter at a time, across the avenues of Alphabet City. But it was beautiful despite (or perhaps because of) its futility.

Pan in on the outside of the Faculty of Law building at Oaxaca’s university. Through a smashed window, a burnt computer monitor, a wrecked office, papers strewn about.

I first met Brad in 1998 at a squatted tenement building next to an overgrown community garden at 136th Street and Cypress Avenue in the South Bronx. The garden and squat formed an oasis in the most blighted part of a blighted neighborhood, on a triangle of land defined by the elevated Bruckner Expressway, a municipal bus parking lot, and the poverty-ridden high-rises of the Millbrook Housing Projects. I had never been involved in activism before, hadn’t even been aware it existed, but my girlfriend at the time had coaxed me up to the squat, where a group was organizing to fight Mayor Giuliani’s plan to auction off 125 community gardens. The gardens, little patches of green scattered across the poorer neighborhoods of New York, were on land that had been defaulted to the city decades before. Once the neighborhoods began gentrifying, Giuliani saw his chance to unload some surplus inventory to developers and settle a few political scores with a demographic that he saw as being “stuck in the era of communism.”

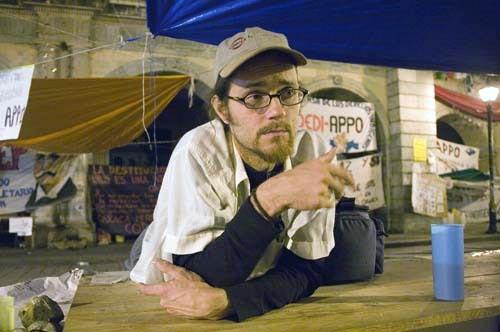

Brad was four years older than I was, tall and slim with a long ponytail and scraggly beard, glasses mended with copper wire. He was always laughing, always talking, always throwing his arm around people and telling stories: a manic, hyperkinetic raconteur. He knew everything about everything, from train hopping to tree climbing, and exuded a kind of confidence that could easily come across as arrogance, except for the fact that he was infectiously friendly with everyone he met. I idolized Brad, and resented him at times, for his breadth of experience and his easy charisma. In those early years in New York, mostly I wanted to be like him.

The squat and garden became the organizational headquarters for a growing movement, and throughout the winter activists from around the city would meet there to plot a way to stop the auction, Brad often plucking out protest-songs-in-progress on his guitar as we cooked rice and beans over an open fire, the towers of Midtown sparkling in the distance. They were exciting times, Giuliani playing a perfect stock villain, and we were all possessed with a revolutionary fervor. In February, thirty of us were arrested for staging a sit-in inside City Hall, singing “This Land Is Your Land” at the top of our lungs, disorderly voices echoing in the building’s vast ornate rotunda. Both Brad and I were dragged to waiting paddy wagons in flex-cuffs by the NYPD and locked up overnight in Manhattan Central Booking, where we used the echoing concrete walls to harmonize a sing-along with our fellow prisoners. It was the most fun I’d ever had, and I felt as though I’d been inducted to some secret club that was trying to save the world.

A dusty street scene, a man, shading his eyes from the tropical sun, speaking in Spanish as a truck burns in the background. He explains that the truck belonged to the paramilitaries. Cut to a woman speaking, voice energized with anger, saying that two armed men were chased away before the vehicle was set alight. “No somos maestros, somos el pueblo,” she repeats over and over again. We are not teachers, we are the people. We are struggling for our rights. Boys in masks, holding tire irons, stand behind her. Far off, a popping noise, maybe gunshots, maybe tires exploding. “When Ulises leaves Oaxaca, in this moment we will have peace.” The crowd, swelling with her tirade, begins a chant: “¡El pueblo, unido, jamás será vencido!” The people, united, will never be divided.

A few months later, with the auction still slated to proceed, we stepped up our tactics. I came up with a scheme to climb a tree in City Hall Park dressed as a sunflower. I had built the costume for Halloween the previous year, a corona of yellow petals made of satin curtain material stretched over bent coat hangers. The idea was to climb a large ginkgo tree at the corner of the park and not descend until the mayor came out and talked to me. Perhaps unlikely, but given our lack of political clout it seemed like a good attention-getting plan. I scrambled up into the tree at around 9 a.m. on a Friday morning and, sitting on a high branch, put on the sunflower headdress. I sat up there for a while before anyone even noticed, Brad and the rest of my friends milling around on the sidewalk below. But a policeman finally looked up, and we knew we could count on Giuliani’s shock troops to overreact. Within a half hour, a dozen squad cars had pulled up, and the scooter patrol, and several vehicles of the city’s Emergency Services Unit, including one with a large boat strapped to the roof.

I was starting to get nervous, and the thought of a night in central booking, alone, became less and less appealing. I shouted down to Brad (a veteran of the old-growth forest campaigns in the Pacific Northwest, he had much more experience in these sorts of things), asking him what I should do.

“Well, whenever you come down, they’re going to put you through the system,” he called up to me. “So you might as well hang out up there for a while and stay free.”

So I did. The police inflated a huge suicide-jumper air bag beneath the tree, which seemed a bit dramatic given that I was only twenty-five feet from the ground. Then they put a ladder against the trunk, and sent an emergency services officer in full climbing gear up the tree after me. After a brief negotiation, and noticing that the bank of television cameras had finally arrived, I agreed to come down without being hog-tied. I grinned for the cameras as they stuffed me into a paddy wagon, and spent the night in the fluorescent-lit, institutional-green dungeon beneath the Criminal Courts Building. But I was glad I’d listened to Brad, as the stunt did the trick. The headline in the New York Times read “Plant Lover Up a Tree Is Pruned by Police.”

Zoom in on the burning truck, now reduced to a blackened frame sitting on its axles, orange flames billowing into an oily black plume that rises into the perfectly blue sky. There is no sound but the crackling of the flames.

A few days later, Brad and two others were arrested inside the offices of the city agency that was running the auction, having locked their legs together with Kryptonite U-locks in the middle of the floor. The New York Times called our tactics “increasingly eccentric,” but public opinion had swung in our favor, and a few days later the auction was called off. Giuliani, under increasing pressure to avoid a public-relations debacle by bulldozing the gardens, cut an eleventh-hour deal with a land-preservation group, and all 125 plots were preserved in perpetuity. It was an enormous victory, and we sensed that Giuliani felt his political mortality for the first time.

The garden fight was for me the beginning of a great love for causing trouble, of pushing myself to the boundaries. I got involved with environmental and political activism, which led all over the country, from Earth First tree-sits hundreds of feet above the ground in Oregon to rolling street-battles during the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in 2000. And everywhere I went, Brad was there, strumming his guitar and singing until his voice was hoarse, flirting with wide-eyed girls on spring-break activism vacations, teaching people how to dumpster-dive or chain themselves to bulldozers or play a progression of chords. At every protest Brad was rattling the barricades, moving as close to the battle as he could, like a Sioux warrior counting coup. And he always seemed to get away. He loved it. Lived for it.

Cut to a street, the camera jolting and panning across the ground. Shouts, and the pops of gunfire are louder, closer. The camera, jerking dizzily over the asphalt, moves quickly to shelter behind a large red dump truck.

It was a heady time, starting with the 1999 World Trade Organization riots in Seattle, the IMF–World Bank protests in Washington, the Free Trade Area of the Americas summit in Quebec City, the 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia. Each city was the site of huge convergences of activists from all over the country, bent with some (certainly naïve) notion that smashing things would change the world for the better. I was intoxicated by the shouting crowds, by the theatrical conflicts with the police: the cat-and-mouse thrill of almost getting arrested and escaping, the sting of drifting tear gas. In Quebec I threw snowballs at the police as they shot hard plastic “baton rounds” and threw tear gas grenades into the crowds. I ran into Brad on the street there; he was late because he’d been caught trying to sneak across the border on a freight train. The Canadians were nice enough to release him on their side of the border, and he came straight to Quebec for the fun. And it was fun, never much more to worry about than a bit of pepper spray in the eyes, at worst a poke with a baton. I washed Brad’s eyes out with water once, as he blinked and squinted from the CS tear canisters launched into a crowd of protesters by the Washington, DC, police. He was laughing as I tried to rinse his clenched-shut eyes, tears and water running down his face, telling me the story of how he had ridden his bike straight into the cloud of gas. Of course we believed in what we were doing, but it was the energy in the streets, the sheer punk-rock abandon, that brought us and thousands of others to the fight.

On the Lower East Side, we holed up in a squat and barricaded it like a medieval fortress, welding the doors shut from the inside and wrapping the fire escapes with razor wire. We rode in Critical Mass rides, a thousand bicycles in a vast rolling carnival, blocking intersections and seizing the car lanes on bridges to defy the primacy of the automobile. In Colorado one summer we worked on a campaign to stop the Vail ski resort from expanding into a wilderness area, setting up a blockade of a flipped-over car on a logging road; we built a tree platform, carrying the materials 10,000 feet up a mountainside to keep old-growth forests from being cut down.

The following summer Brad and I rode with two friends in an open boxcar from the outskirts of New York all the way to Bristol, Tennessee. We spent days rolling through Appalachia, staring out at the backyards and junkyards of America, Amish buggies and Fourth of July fireworks cinematically framed in the open door of the boxcar. When the train sided somewhere in Virginia, Brad got cocky and decided to go up and have a chat with the engineers. I don’t know if they dropped the dime on us, but when we rolled into the yard in Bristol at dusk we found a cop car waiting for us. We got to eat dinner (bologna on white bread, and Jell-O) in the city jail while they wrote us our trespassing tickets. But all the adventures, all the incomparable scenes, even the brushes with the law reinforced some deep sense that we were doing something revolutionary.

We even kissed each other once, in a darkened room at a New York City squat, while both of us fumbled with the same girl and our own idealized notions of “free love”—the three of us rolling on a mattress on the floor. There was no electricity save for the filtered streetlight coming through the broken-paned windows, and the noise of the city seemed distant, like waves breaking on a shore. It was one of those hours when the desire to bring justice to the world and the love we all held for one another seemed expressions of the same fierce hope. It seemed so innocent, and we were intoxicated with that sense of freedom and possibility. We both certainly broke enough hearts trying to love that way, but I think this was Brad as his purest self, trying to live by Emma Goldman’s maxim: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be in your revolution.” Flawed, utterly human, Brad loved the world and the people in it, and tried to share that feeling as best as he could. We never talked about the night afterwards, but I always remembered it. So I knew that spot well, the smooth skin just below his ribs, where the perfect, bloodless hole appeared. I had rested my head there once.

The sun now behind him, the shadow of the cameraman is framed for an instant on a sunlit patch of the oil-stained street, before being swallowed up in shadows behind the truck. It is the first moment in the footage that the cameraman is captured, a brief flickering shade, Brad and his camera, traced on the ground.

Brad always went farther afield than the rest of us. He was restless, nomadic, and would disappear from the city for months at a time. He had friends all over the country and the world, made a point of knowing everyone everywhere, and crashing on their couches. Martyrdom is dehumanizing: I feel as though I’d be doing a disservice to his memory if I didn’t point out that Brad was a mooch par excellence, but the fact that he would eat everything in your refrigerator while you were at work was more than offset by his generosity with anything he had, or anything good he had found in the trash. He believed in sharing on all levels.

Seattle had set off a worldwide movement, and he traveled to the anti-globalization protests in Prague, where phalanxes of anarchists pushed the police lines back with inner-tube shields. But the street theatrics grew more violent. At the G8 meeting in Genoa in July 2001, a young Italian anarchist named Carlo Giuliani was shot in the head as he attempted to throw a fire extinguisher through the back window of a police car. None of it deterred Brad. He would waltz back into New York with epic stories of European street battles, where ancient cobblestones were pried up with crowbars and tossed at the police. I never saw him being violent myself, but he loved to be close to the hottest part of the action, to come back smelling of tear gas with a wide grin and an inexhaustible supply of stories.

On the morning of September 11, right after the towers had fallen, I was standing on the corner of Chambers and Greenwich and staring in stunned silence at the smoking mountain of warped steel and powdered concrete four blocks to the south. Out of a crowd of thousands, Brad rolled up to me on his bicycle, grim and serious, but with that same excited spark in his eyes I had seen a thousand times before. That look that said, It’s on. Even though neither of us could begin to comprehend the significance of the scene we were witnessing, amid that horror I somehow found his presence immensely comforting.

But something shifted after that, not just in the vast reordering of the geopolitical calculus, but in my own sense of what we were doing, what activism could achieve. The free pass that Starbucks-smashing Seattle-style antics had been given by the press and in the popular imagination was soon revoked. Giuliani, our stock villain, had suddenly been transmogrified into Winston Churchill. In a historical moment sown with such Orwellian terms as Operation Infinite Justice, Total Information Awareness, the Patriot Act, and the Department of Homeland Security, anyone with the label “activist” was suspect.

More pops, small arms fire. The camera moves forward, Brad filming from a prone position on the ground underneath the truck. Zoom out between the wheels to a group of men, a hundred feet away, standing around casually as the shots echo. One throws a rock, lazily, apparently at no one, as if warming up a pitching arm. A man on a bicycle rolls slowly through the frame, seeming bizarrely nonchalant, almost indifferent. More shots. Framed by the axle and tires of the truck, the men start walking off to the left of the frame, looking back over their shoulders.

In the months after 9/11, I found myself drifting away from the activism scene. I hated the interminable meetings, hated the obsession with process and consensus, the way the nascent antiwar movement was knee-jerk and lacked any coherent message. Something, clearly, had changed, and the movement didn’t seem to know how to adjust. Or maybe something had changed in me, some crisis of faith or confidence, and my warring impulses of cynicism and idealism had sapped my desire to march anymore. In any event, I thought my sensibilities worked better as a reporter, as a storyteller, and I started down a path toward journalism. The following year I moved to India, and started reporting stories for magazines in the States. But I was still drawn to those anarchic fringes, where conflicts were simmering below the surface, where people were angry at injustice and wanted to do something about it. I reported from Tamil Tiger territory in Sri Lanka, rode a motorcycle through Kashmir, walked through minefields in Afghanistan, interviewed a gun shop owner in the Khyber Pass and desperately poor people in the slums of Bombay and Manila and Nairobi. I don’t know if any of the dispatches I filed from those far-off conflicts helped the people I documented in any measurable way. But I was drawn to those places, the strangeness was exciting, and the risk, measured as it was, added to that. Staring off the edge of the world and reporting what I saw there made me feel more fully alive.

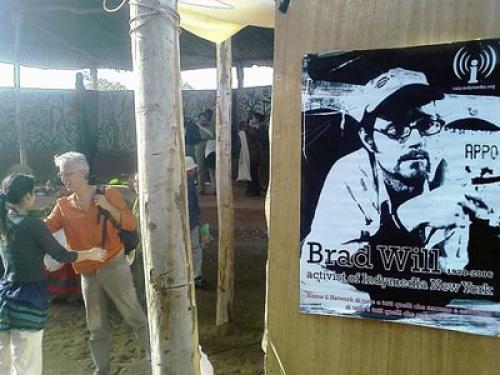

Brad, in his own way, did the same thing, but he went much deeper in the direction he’d been going, closer to the pure energy of oppressed people taking justice into their own hands. He was attracted to struggles for land, for autonomy, for democracy, the greater iterations of the things he’d been involved with in America. Somewhere in that time, Brad picked up a camera. He started working for the Independent Media Center, also known as Indymedia, an organization that sets up collective-run news outlets. Beginning with the Seattle protests, Indymedia collectives were set up in many different countries, with volunteers documenting social justice, human rights, and protest movement stories that are largely overlooked by what they derisively call “corporate media.” The Indymedia movement itself, when not ignored, is dismissed by traditional media outlets as radical and biased. Despite its political agenda, Indymedia has documented the struggles of largely voiceless people around the world. Brad set out to do just that, and his instincts drew him toward where the action was, toward the nascent popular uprisings scattered across Latin America; in Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru, Argentina, and finally Mexico. It all led inexorably to that final afternoon in the Oaxaca suburb of Santa Lucia del Camino.

Cut again, the sound of feet running, camera pointed at the ground. There are few pauses in the recording now, the raw film taking in the undistilled chaos of the scene. Brad’s feet pop into the frame, blurred, as he jogs along. His creeping shadow is projected again onto a garden wall, overhung with plants, splashed with graffiti.

One of his earlier Latin American dispatches, and the first inkling to his friends of the trouble he would later encounter in Mexico, came when he went to document a massive squatter encampment called Sonho Real, “Real Dream,” near the city of Goiânia in the Brazilian interior. Writing in the rapid-fire style that drove his editors nuts (he would sometimes substitute dashes for all other punctuation) he described the place, an idealized version of the land struggles he had first encountered in New York City: “They had built a dream in the dust—a new people’s village, a giant squat, a community.” He fell in love with the people there, and their project, but the stakes would soon prove to be much higher than anything he had known before.

After weeks of harassment, the encampment was stormed by thousands of Brazilian military police, firing tear gas and what Brad imagined were real bullets: “They have such a distinct sound as they whiz by your head.” The encampment was overrun, people were beaten, shot, dumped in wells. Then the police found him:

They came screaming, but I could only understand bits and pieces. I was explaining I was a journalist from the U.S.A. The police, with their pistols pointed at my head, didn’t seem interested in my credentials. When they hit me it was first in the back of the head, then one threw me down, three or four kicked me, then one on top hard with his knee in my back. Then the plastic handcuffs like a vise. I got on my feet looking for my video camera. What the fuck happened?

Life and death can be cheap in Latin America, with its long and brutal history of political and social unrest and government repression. Democracy is a relatively new thing and largely notional when it comes to conflicts over land and power. The ability of the press to serve as a check to state violence is limited. The police are more likely to use real bullets, people are more likely to disappear. Four students killed at Kent State was a seismic event that shook the American government to its foundation. In Mexico, as many as four hundred protesting students were killed or disappeared in 1968’s Tlatelolco Massacre, and it took almost thirty years for an official investigation to be opened on “Mexico’s Tiananmen.” What are a few deaths? Brad was badly shaken by what he witnessed in Brazil, and also knew that, despite being roughed up, his status as a white journalist, even from a nontraditional outlet like Indymedia, conferred some degree of protection on him. He “realized they were being gentle.” But I think he also secretly felt that thrill, the tiptoeing up to the cliff’s edge and peering over. In Latin America the stakes were raised, and he wanted to take part. He loved the cat-and-mouse frisson of taunting those powerful enough to destroy you and scampering away. The “distinct sound as they whiz by your head” makes not just for breathless storytelling for friends back home; the rush becomes a deep craving, a desire to push further toward the limits of experience. As Winston Churchill wrote when he was a young correspondent during the Boer War: “There is nothing more exhilarating than to be shot at without result.”

Does any of this render Brad’s ostensible reason—to give voice to the voiceless, to document the struggles of those who are trying to make a place for themselves in a world rife with corruption and oppression—any less valid? Much of American journalism makes a great show of its pursuit of objectivity and fairness. A few hours with a remote control watching the “Fair and Balanced” 24-hour news circus should dispel any notion that that’s more than lip service to the idea of integrity. It would be better for us all, I think, if the media just came out and stated their biases from the start. It is possible to be a partisan and a clear-eyed observer. George Orwell fought in the Spanish Civil War in a Marxist battalion, was shot through the neck and nearly died, and within a year had written a book that stands today as a singular achievement of twentieth-century journalism, at once prophetic and level-headed not only about the gathering threat of Fascism, but of Stalinism as well. Journalists are clearly not saints. Nor should they expect to be. Whatever fix or thrill his work provided, whatever lay at the core of his motives, Brad was doing what he believed to be the right thing by his own lights. However naïve or misguided his reasons may have been, he didn’t deserve to be murdered for them.

A group of young men, T-shirts over faces, wearing baseball caps, holding sticks, shouting, sprinting toward the camera and past it. “¡Vamos! ¡Vamos! ¡Vamos!” The camera turns and follows, sticking to the wall along the edge of an alley. Boys, sweatshirt hoods pulled up, fire slingshots and duck behind cars. A shot is fired from behind a wall, and the group of boys, armed with slingshots and pipes, charge a steel door in the wall, kicking it briefly open before it is slammed shut from within. They run at the locked door with flying kicks, screaming and cursing.

The last time I saw Brad was in August 2006. I was reporting a long story about a group of punks from Minneapolis who were drifting down the Mississippi on a homemade raft. After weeks on the river, we planned to stop at an anarchists’ convention being held on an island in the river near Winona, Minnesota. Pulling up at midnight, I waded ashore through the brown river water, carrying the anchor rope. There was Brad, standing in the darkness on the beach. He handed me a beer. “You always make such an entrance,” he said, laughing. I could have said the same about him. He was teaching workshops, playing guitar, having a bit of summer fun before heading back down south in the fall. Neither of us had known the other would be there, and it seemed to me one of the ordinary miracles of knowing Brad: he always showed up. And that expected-unexpected quality, that recurrence, makes his permanent absence afterward almost impossible to believe. Of course he’ll come back.

We talked a lot about traveling in the far-flung places of the world, and he was very curious about how I’d managed to make a go of writing for a living. He always had to scramble in between travels, working long hours as a lighting rigger in New York to save up money for his forays south. I was making a living as a journalist, true, but it came with a host of attendant compromises to make work palatable to commercial magazines. Selling out, so to speak. We each seemed to think the other had a good racket going on, and for both of us it was as much about the adventure as the work itself. We had each been in dangerous spots, and knew risk was an issue, but we both seemed to understand that it was inherent in life, and we never once talked about it being something to worry about. Certainly nothing to prevent us from going places. Certainly nothing that could get either of us killed. Brad also told me for the first time that he had a child, a four-year-old son in France being raised by a woman he had had a brief affair with. She didn’t want him to help raise the boy, and Brad seemed content with not being tied down to fatherhood, so he could continue the work he was doing. Whether this was a dereliction of responsibility, and whether he had any intention of one day being part of the boy’s life, I have no idea. Nor do I know if Brad’s child will ever find out what kind of man his father was or what happened to him. However he lived with his conscience, Brad felt called elsewhere. “I’m going to Oaxaca,” he said, savoring the syllables. “There’s a revolution going on down there.”

More shots, from somewhere else, the camera clings to a wall, peering out from the edge of a bush. A man, unmasked, collared shirt neatly tucked in, comes with a long length of pipe and bangs on the door, trying futilely to ram it open. More shots and the crowd scatters, running away down an alley, joining a larger group of boys who are throwing rocks. They begin chanting. “¡Zapata vive! ¡La lucha sigue!” Zapata lives. The struggle continues. More gunshots. The crowd runs down the street. The frame jerks back and forth, frenetic, the camera aimed backward as it moves with the crowd, running from the direction of the shot.

The latest conflict in Oaxaca, the picturesque colonial capital of Mexico’s second-poorest state, began on June 14, 2006. For a quarter century, Oaxaca has been the site of an annual state-wide teachers’ strike, where as many as 70,000 school workers stage a protest encampment to advocate higher wages, better school funding, and better treatment of the indigenous population in the largely native southern state. The strike was usually a low-key and well-rehearsed event, as much political theater as anything else. There were marches and chanting, a few minor concessions, and then everyone went home. In June, the state’s governor, Ulises Ruiz Ortiz, threw a rock at the hornets’ nest, sending 3,500 policemen in the middle of the night to break up the encampment that had taken over the zocalo, the historic plaza in front of the city’s sixteenth-century cathedral. It turned into a bloody riot: cars were set alight, and tear gas was fired into crowds of teachers, who beat back the police with sticks and rocks.

In response to Ruiz’s actions, activists poured in from across the country, and a broad coalition was formed under the acronym APPO (the Spanish abbreviation for Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca). They proceeded to expel Oaxaca’s police and entire municipal government, take over dozens of private radio stations in the town, and block off hundreds of streets with homemade barricades. Much of the inspiration for the uprising came from the Zapatista movement in neighboring Chiapas, an indigenous army led by the charismatic and mercurial Subcomandante Marcos. On January 1, 1994, the day after NAFTA became law, the Zapatistas had taken over five towns in Chiapas, posting demands on their website for indigenous rights and autonomy, in what was often called the “first post-modern revolution.” Though the violence was relatively brief, the uprising served as a huge inspiration for anti-globalization groups around the world. I had seen Marcos give a speech in Oaxaca in 2001, in the zocalo, but at the time his revolution had seemed already to be a product, with Marcos T-shirts and Zapatista dolls on sale around the plaza. Marcos was famous for his trademark black balaclava and pipe, as marketable an icon of revolutionary cool as El Che in his beret. The Zapatistas’ campaign, where they toured from city to city on buses holding rallies, was nicknamed Zapapalooza by the activists who came down from the States to join it, at least aware of the irony of their groupie status. The most dangerous situation I encountered then in Oaxaca was some dodgy tamales from a street vendor.

But something had changed by the summer of 2006. Whatever long-held resentments the poor of southern Mexico held against the entrenched political powers came bubbling to the surface. APPO loathed Ruiz, a holdout of the recently ousted Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) which was voted out in 2000 after seven decades of control in Mexico. Ruiz, a PRI hard-liner who was popularly believed to have stolen the most recent state election, was the focus of the protesters’ rage. They had a chant: ¡Ya cayó, ya cayó, Ulises ya cayó! He’s fallen, he’s fallen, Ulises has already fallen. But of course he hadn’t, and with Oaxaca’s lifeblood of tourism essentially shut down, and hundreds of armed police and paramilitaries turned out of the city center, the situation grew increasingly tense, fractured, and violent.

A red dump truck, commandeered by masked men, is backed down the street, serving as a moving barricade for the crowd. Still more gunshots, and boys throw rocks in their direction. The truck seems to be used to try to ram the door open, moving forward and backing into it again and again. There are more shots, and the driver jumps out of the cab and runs away.

On September 26, packing to leave New York, Brad sent an e-mail to Al Giordano, an activist he’d known in New York who now runs a website called the Narco News Bulletin, filing dispatches on the drug war and democratic struggles in Latin America.

Giordano later posted their exchange on his site—

From Brad:

hey al

it brad from nyc-it would be great to get yr narco contacts in oaxaca-i am headed there and want to connect with as many folks as posible-are you in df [the Federal District of Mexico City]?-i should be stopping though there and it would be great to go out for a drink solid

brad

Giordano wrote back:

Our Oaxaca team is firmly embedded. There are a chingo of other internacionales roaming around there looking for the big story, but the situation is very delicate, the APPO doesn’t trust anyone it hasn’t known for years, and they keep telling me not to send newcomers, because the situation is so fucking tense . . . If you are coming to Mexico, I would much more recommend your hanging around DF-Atenco and reporting that story which is about to begin. The APPO is (understandably) very distrustful of people it doesn’t already know. And we have enough hands on deck there to continue breaking the story. But what is about to happen in Atenco-DF needs more hands on deck.

Brad replied the same night:

hey

thanks for the quick get back-i have a hd professional camera-i have heard reports about the level of distrust in oax and it is disconcerting-i think i will still go-i wont tell them you sent me and i am open to other suggestions on how to spend my time-i dont know what is happening in atenco in the coming days-i may connect with la otra capitulo dos somewhere along the way-great to hear from you-do you have a cell / phone number?

solidaridad

b rad

(he often signed his missives “b rad,” punning his own name into a command to “be rad.” I imagine he meant “radical” in all its senses.)

There was no way to talk him out of something he wanted to do, and what Brad wanted to do was dive in to the middle of the fray that was going on in Oaxaca. Using a camera as both a weapon and a shield seemed the best strategy to bring himself close to the conflict and still do something to help.

Most Americans know almost nothing about the social and political problems of Mexico, except when they manifest themselves in the millions of illegal immigrants pouring over the border. And our response? Paranoiac minutemen patrolling stretches of desert as self-appointed border guards, or the erection of a multi-billion dollar wall that would have made the Ming dynasty envious. Brad believed that we ignore the suffering on the other side of our border at our peril, and he went down there, with a camera he bought on eBay, to do something about it.

Brad flew to Mexico City and made his way down to Oaxaca, connecting with other Indymedia people there, and within a few weeks he was camping out in the zocalo, acting as a human rights monitor, camera in hand. He must have felt in his natural element, despite the fact that his Spanish was not very good, and the situation was growing increasingly tense as PRIista paramilitaries sniped at the barricades around the city. Several members of APPO were gunned down in the early weeks of the autumn.

Cut to a street, behind a group of hooded men, watching down a dirty alley lined with concrete and cinder-block homes. There are odd gunshots, but the gunmen are hidden, somewhere in the jumble of trees and houses in the distance. Young men, masked, wearing backpacks, some shirtless, hunch down and face the direction of the shots. Someone sets off a bottle rocket in the direction of the gunfire, and it whistles down the street, trailing white smoke and erupting with a theatrical bang, louder than the real shots. More pops of gunfire in return. The crowd surges forward and crouches low by the roadside. Everything is still for a few moments, and the masked figures, huddling before the camera, look around uncertainly.

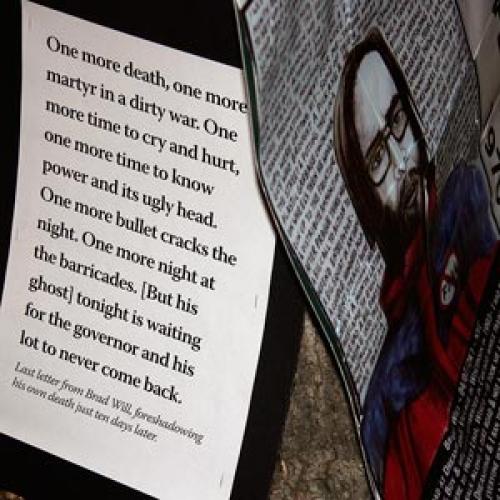

Brad’s written dispatches were stream-of-consciousness prose poems, fired off in e-mails to be posted on websites back home. While he may have had ambitions to do “serious journalism” (or at least get paid for it), he never tried to write for an audience outside the relatively small world of global activism (as evidenced by his punctuation). But the rawness and immediacy of his dispatches had their own fierce beauty, like the last one he submitted to Indymedia, about going to the morgue to see the body of a man who had been shot in the head while guarding a barricade. He wrote the dispatch eleven days before he himself was killed, before he was laid out in that same morgue, and it is an eerily prophetic testament to what he was witnessing on the streets of Oaxaca:

early dawn, oct16

yesterday i went for a walk with the good people of oaxaca – was walking all day really – in the afternoon they showed me where the bullets hit the wall – they numbered the ones they could reach – it reminded me of the doorway of amadou diallos home – but here the grafitti was there before the shooting began – one bullet they didnt number was still in his head – he was 41 years old – alejandro garcia hernandez – at the neighborhood barricade every night – that night he came out to join his wife and sons to let an ambulance through – then a pickup tried to follow – he took their bullet when he told them they could not pass – they never did – these military men in civilian dress shot their way out of there

a young man who wanted to only be called marco was with them when the shooting happened – a bullet passed through his shoulder – he was clearly in shock when we met – 19 years old – said he hadnt told his parents yet – said he had been at the barricade every night – said he was going back as soon as the wound closed – absolutely

just days before there was a delegation of senators visiting to determine the ungovernability of the state – they got a taste – the call went out to shut down the rest of the government – dozens went walking out of the zocalo city center with big sticks and a box full of spray paint – they took control of 3 city buses and went around the city all morning visiting local government buildings and informing them that that they were closed – and we appreciate your voluntary cooperation – and they filed out preturbed but still getting paid – shut – as they pulled away from the last stop 3 gunmen came out and started shooting – 2 buses had already pulled away – mayhem – 10 minute battle with stones and slingshots and screaming – one headwound – another through the leg – made their way to the hospital while the fighting continued – shout out on the radio and people came from all parts – the gunmen were around the side of the building – they got away – they were inside – no one sure – watchful – undercover police were reported lurking around the hospital and folks went running to stand watch over the wounded

what can you say about this movement – this revolutionary moment – you know it is building, growing, shaping – you can feel it – trying desperately for a direct democracy – in november appo will have a state wide conference for the formation of a state wide assemblea estatal del pueblo de oaxaca (aepo) – now there are 11 of 33 states in mexico that have declared formation of assemblea populares like appo – and on la otra lado in the usa a few – the marines have returned to sea even though the federal police who ravaged atenco remain close by – the new encampment in mexico has begun a hunger strike – the senate can expell URO – whats next nobodies sure – it is a point of light pressed through glass – ready to burn or show the way – it is clear that this is more than a strike, more than expulsion of a governor, more than a blockade, more than a coalition of fragments – it is a genuine peoples revolt – and after decades of pri rule by bribe, fraud, and bullet the people are tired – they call him the tyrant – they talk of destroying this authoritarianism – you cannot mistake the whisper of the lacandon jungle in the streets – in every street corner deciding together to hold – you see it their faces – indigenous, women, children – so brave – watchful at night – proud and resolute

went walking back from alejandros barricade with a group of supporters who came from an outlying district a half hour away – went walking with angry folk on their way to the morgue – went inside and saw him – havent seen too many bodies in my life – eats you up – a stack of nameless corpes in the corner – about the number who had died – no refrigeration – the smell – they had to open his skull to pull the bullet out – walked back with him and his people

and now alejandro waits in the zocalo – like the others at their plantones – hes waiting for an impasse, a change, an exit, a way forward, a way out, a solution – waiting for the earth to shift and open – waiting for november when he can sit with his loved ones on the day of the dead and share food and drink and a song – waiting for the plaza to turn itself over to him and burst – he will only wait until morning but tonight he is waiting for the governor and his lot to never come back – one more death – one more martyr in a dirty war – one more time to cry and hurt – one moretime to know power and its ugly head – one more bullet cracks the night – one more night at the barricades – some keep the fires – others curl up and sleep – but all of them are with him as he rests one last night at his watch

That dispatch and Brad’s last footage were all the puzzle pieces his many friends had for understanding what had led him there, to Avenida Juárez on the afternoon of October 27. He felt in Oaxaca he was bearing witness to something truly important, a spark of revolution, the essence of what he had been fighting for for years, the great hope for a world where justice was not a commodity in the hands of the powerful. But what was going through his mind, moment to moment, as he raced around the city, a roving, mortal eye witnessing the day’s events? What was he thinking as he lay under that truck? Why was he following those boys through the streets as they threw rocks at gunmen? Did he believe that the images he was chasing down were worth the risks? Was it a game of cat and mouse, like we and our friends had played time and again with the NYPD, with loggers and sheriff’s deputies out west, with railroad bulls? He had no death wish, I am convinced of that. Brad loved life far too much, loved food, loved women, loved seeing the world from the open door of a boxcar. Was he afraid as the bullets were cracking all around him, or did he ignore them? His hand on the camera is amazingly steady, given the circumstances. Was he naïve about the purity of this revolution, and the reality of the hazards he faced? Was he afraid at the end, or did he feel some kind of peace? There are so many questions I’d like to ask him, and it still seems impossible to believe that I never will. I think in the end that he was swept up in the adrenaline surge of the moment, and simply didn’t believe he could get shot.

A single pop is heard, and almost simultaneously there is a loud wet splat, like an egg breaking on a sidewalk, amplified by its proximity to the shotgun mike mounted on the camera. A surprised scream, piercing, overloads the microphone to static, and the camera swings toward the asphalt, still recording, like the black box of a doomed aircraft. Brad is heard yelling, “¡Ayudame!” Help me. Panicked shouts and running feet, and the dangling camera swings uncontrolled, back and forth, as it is carried away from the gunfire. More shots ring out, and there is a blur of motion, of legs running, of flashing masked faces.

The camera is placed on its side on a stone bench, still recording. Its insensate lens, no longer subject to human will, is focused on the bench, the street, a tree, the whole scene turned on its edge. There is a wet spot, perhaps blood, a few inches away on the stone. The camera’s frame, which for the duration of the footage has bounced and jerked and zoomed dizzyingly, is utterly, eerily still. The last figures have run out of view, and nothing at all moves, except a fringe of silhouetted leaves in the tree, shaking in the breeze. Shouting is still heard, and a dozen more shots ring out in quick succession before the tape cuts to black.

And that was all. I watched it the first time, on YouTube, my eyes peering out between my fingers, shaking uncontrollably, my heart in my throat and scarcely able to breathe. I wanted to shout out to him, to warn him, but the footage seemed inevitable as it unspooled, the digital counter ticking down the seconds Brad had left to live. I walked around for several days stunned, a dull sick ache in my chest. The feeling seemed to be exactly where the bullet wound was, a couple inches below his sternum. I couldn’t bring myself to watch the video again for six months.

There were still images as well, shot by other news photographers who were on the scene. Brad was carried by a group of masked men, his shirt pulled up to reveal a small, perfect red hole, dead center in his torso. Another wound is visible, apparently received when he had already fallen. That bullet pierced his ribcage and lodged in his hip. Arms splayed, a gesture almost like representations of the Pietà, or Goya’s Third of May 1808. His expression is calm, though all the people around him have looks of distress and exertion as they carry him, his skin already ashen, the color of martyrs in the murals of Diego Rivera or José Clemente Orozco. Eyes, heavy-lidded, unfocused, as if already looking out beyond the world.

They put him in a Volkswagen Bug to bring him to the hospital. It ran out of gas. They tried to flag down cars, but none would stop, afraid of all the violence that was erupting in the city that day. Brad was still alive, weakly squeezing the finger of one of the men who was trying to help him. They abandoned the car and tried to carry him on the roadside. He died a few blocks away from the hospital.

Brad’s death, being so inherently, dramatically political, was inevitably politicized. There was much parsing of terms in the press after Brad’s death: “media activist” or “anarchist/reporter” or “journalist and activist.” Some said he was in over his head, drew comparisons to the death of Rachel Corrie, a young American activist run over by a bulldozer while trying to stop a home demolition in the Gaza Strip. The rhetoric of martyrdom was bandied about. But Brad was only one of dozens who had been killed in the months of bloody protests. He would have thought it obscene that after so many deaths, so much violence, it took the death of a gringo journalist to focus the news cycle, briefly, on the conflict in Oaxaca. Mexico’s president, Vicente Fox, who until then had kept the federal government on the sidelines to avoid widening the conflict, sent 4,000 police to break up the demonstrations. There were more clashes, and more people died, but the stepped-up government presence quickly overwhelmed the ad hoc defenses of the protesters, and the occupation of the city center evaporated. It was a bitter irony: the movement that Brad had gone down to witness and support, that he had died trying to document, was crushed by the state because of the negative publicity over his death.

Did his presence there, and ultimately his death, help the people of Oaxaca in any appreciable way? Was he a misguided idealist, getting himself involved in a conflict where he didn’t belong? The same could have been said about Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, civil rights workers who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi in 1964. Schwerner and Goodman were Jews from New York City and had gone to the South to promote voter registration drives; Chaney was a 21-year-old black organizer and activist. They were out of their element too, and their murders were a rallying cry for the civil rights movement and the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Whether any lasting change comes to Oaxaca as a result of Brad’s murder, and the killings of so many others, remains to be seen.

In New York, the activist community was devastated. Everyone had known Brad, everyone knew something should be done. A demonstration in front of the Mexican consulate a few days later erupted into chaos, Brad’s friends chaining themselves to the gates, lying down to block traffic, smashing at the doors, climbing street lights, sobbing in a catharsis of grief and rage. A dozen people were arrested.

I felt numb and silent, watching the melee from the sidewalk across the street. Later I sat in Brad’s apartment with a bunch of friends and looked into his darkened bedroom to see his guitar, on which he had banged out a thousand songs around campfires and at rallies, leaning silently against its battered case (bedecked with stickers such as “Cars Suck,” “Billionaires for Bush,” and “Giuliani is a Jerk”). That was when I finally cried. He’d traveled everywhere with it; I don’t know why he hadn’t brought it to Mexico. Perhaps he was traveling light and needed the space for his camera equipment.

Hardly anything has been done to bring Brad’s murderers to justice. The dead-eye accuracy of the fatal shot, directly in the center of mass, led many to believe that the killer had not only targeted Brad, but was a trained marksman, possibly a policeman. Two men accused in Brad’s shooting—local town councilor Abel Santiago Zárate and his security chief, Orlando Manuel Aguilar Coello—were detained, but both were released a week later. All the accused are affiliated with the PRI, whose support is needed by Felipe Calderón, Mexico’s new president. Despite calls for an investigation by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Amnesty International, and four members of Congress, very little has been done to bring the killers of any protesters to trial in Oaxaca. In the spring, Brad’s family led a march to the site of his murder, demanding an impartial investigation. In a shockingly cynical move, Oaxaca State Attorney General Lizbeth Caña suggested that Brad had actually been shot by the protesters whom he was filming. The Oaxaca coroner, interviewed by the CPJ, called the suggestion preposterous. But no further arrests have been made, despite the fact that newspapers across Mexico published clear photographs of the paramilitary gunmen who were out that day, and their identities are widely known. Killers of journalists in Mexico have a 92 percent impunity rate. They are almost never charged.

And so Brad joined the populous firmament of Latin America’s disappeared and assassinated. Los caidos—the fallen—are many, from Zapata to Che to the nameless occupants of a thousand secret graves. In an open letter, the masked Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos called Brad a “compañero”—a comrade. He was proclaimed a martyr for the cause of social justice and democracy, but no matter how passionate he was, Brad would never have wanted to be a martyr, mainly because martyrs are dead, and he was profoundly alive. Martyr-dom obscures the reality of the person, changes them into an idea, a name to be chanted, to be put up on a wall as a mural or graffiti.

But since we the living can do with the dead what we wish, I’d rather remember a moment with Brad from the freight-train ride we took down the Appalachians that summer years ago. We stood in the open doorway in the warm air, our feet right on the edge above the flashing sleepers, and watched in awe as the train rolled out over a long trestle, the ground dropping away. We were somewhere in America, and a wide green river—maybe the Potomac, maybe the Susquehanna—shrouded in evening mist and edged with trees, rolled out a hundred feet below us and bent far off into the dusky evening light. Brad whooped with delight as he tried to hold himself steady and snap a picture. The vast world was framed in all its mysteries and all its possibilities in that open doorway, and the last light cast our shadows against the back wall of the boxcar. We were young and alive and free, and it seemed as though the racketing train had somehow taken flight.

Related Interest

- “Oaxaca Sketchbook” by Peter Kuper.

- Friends of Brad Will

- BradWill.org

- Brad Will’s film of his own assassination