It’s almost the regular story. Boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love, move in together, have a baby. Then, boy and girl fall out of love, move out and on to live separate and sometimes lonely lives. But in this story, the boy changes his name to Vanesa and becomes a Paris prostitute, while the girl calls herself Michael and stays behind. They had met in their neighborhood in Lima, and for a while Vanesa didn’t know that Michael had once been an Amelia, any more than Michael knew Vanesa was born Melvin. He thought she was a guy and she thought he was a girl. One night, Melvin stayed over at Amelia’s house. She slept and he didn’t, so he woke her:

“Hey, you’re not a man, are you?”

Amelia half-opened her eyes.

“You’re not a woman, either. So let me sleep.”

Melvin embraced her and they slept.

But in the days that followed, neither of them knew what to do with the relationship. There was no room in Amelia’s head for the possibility of being with a man; she was a lesbian. And butch. And a virgin. Nothing fit.

For Melvin, it was almost as complicated. He considered himself a feminine person, but he’d always liked the role of protector. At the end of the day, he was a man. And his male hormones urged him to act like Amelia’s husband. He’d go looking for her on the street corners of Lima’s rougher neighborhoods, where she often gathered with her friends to drink. He went there to fight with all the men who disrespected her.

“Look, papito,” Melvin said, “it’s fine that you look like a man but you’re not a man. First you act tough, but I’m the one who ends up picking up the pieces. I’m the husband here. Let’s go home, dammit.”

In bed and alone, the who’s-who of social complexities evaporated. Instead of Melvin or Vanesa, Amelia or Michael, they just used pet names. Melvin called Amelia “gordita,” and Amelia called Melvin “cholo.”

When he was drunk Melvin would yell at Amelia. “You’re my woman,” he’d shout. “When I met you, you were just a girl and I made you a woman.”

* * * *

I’ve arrived in Paris this morning on a direct flight from Barcelona, with my cell phone dead and my breasts full of milk. In order to come here I’ve left my three-month-old baby behind, but my breasts don’t seem to have figured this out; they continue their unstoppable production of food and from one moment to the next I fear they’ll burst. I feel so guilty for having left my daughter that I wonder whether this growing discomfort might be my just punishment. The worst part is that I don’t see Vanesa anywhere. It’s rush hour in Charles de Gaulle, and the loudspeakers resound with security warnings that are more and more obscure—they keep shouting something to do with shampoo and liquid explosives. The phone cards in France are terrible. Melvin—I call her Vanesa—answers the phone sounding as if she’s been sleeping with a terrible hangover. She shows up an hour later.

She offered to pick me up from the airport and host me in her apartment this weekend. Based on what she said, everything is going phenomenally well for her. She placed a great deal of emphasis on the fact that she had a car, and an apartment, and that she spoke French very well. She added that she was thinking about studying theater and that she currently worked “on something to do with the internet,” but that she’d explain it to me later.

Vanessa is a transvestite, although she self-identifies as transsexual, despite the fact that she has not undergone a surgical sex change. In Lima, the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Trans (GLBT) collective utilizes the term Trans to group together transvestite, transsexual, and transgender identities. The boundaries are never clear enough for simple definitions.

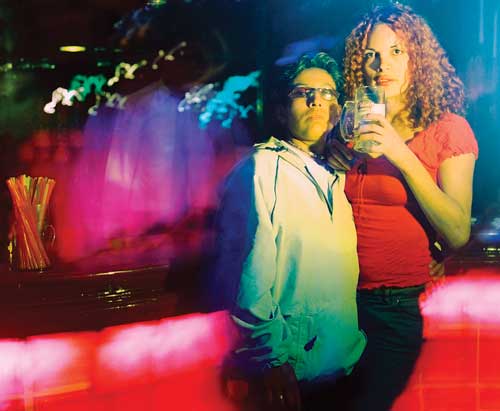

I’d met Vanesa four years earlier in Kapital, the largest discotheque in Comas, one of the most populated and bustling neighborhoods of northern Lima. At that time, Vanesa was undoubtedly one of the queens of nightlife and she captured every gaze with her sculpted figure and red hair. Soon after, however, I learned that she had crossed the Atlantic, following the route to Europe and prosperity that so many transgendered Peruvians had traveled before her. I hadn’t seen her since, until now.

Vanesa arrives at the airport hours late, and without any car in sight. At a distance, she looks the same as she did four years ago, but up close something seems to have deteriorated or disappeared forever. She is very thin and her bony, boyish face is almost lost among her curls, which are recently washed and have not been dried. She has not put on makeup. She is wearing tight jeans, white boots, and a turtleneck sweater. Despite the cold, she wears no coat. For a “transsexual,” she’s not that showy, and I sense that she wants to be seen as a normal woman. Her delicate build and diminutive size allow her to pass.

Once we recognize each other, we walk toward the train and I notice for the first time how the indiscreet gazes of men and women follow that still-voluptuous body. Her potent, truck-driver’s voice surprises them.

“Don’t you know someone in Spain who might want to marry me?” she asks.

Vanesa flirts with all the men who look at her. Every time she sees a more or less attractive one pass, she says to me, “there goes my husband.” She pursues one of them, shouting: “Don’t go, I’m the woman of your dreams.” Then, in Spanish, “Should I suck it for you?” The Frenchmen look at her as if she were asking them for the time.

* * * *

I have seen Serenazgo, a neighborhood security corps in Lima, let loose its dogs and wield nightsticks and tear gas against transsexuals. I’ve seen news coverage of the sweeps through Pampa de las Locas—“crazy women’s prairie”—one of the areas where Lima’s poorest transvestites work. I’ve heard of police operations with names such as Prophylaxis 2006—despite the fact that sex work is not criminalized in Peru. I’ve read in the papers about organized gangs like the now-defunct Mojarras, named after a kind of knife, whose mission was to attack transvestites and sex workers.

Now and then one hears about a transvestite brutally murdered under “strange circumstances” in her hair salon or apartment. According to the estimates of the Homosexual Movement of Lima (Mhol), more than five hundred homosexuals, including transvestites, lesbians, and gays, were arrested on the streets of various Peruvian cities last year, and in the majority of cases these detentions were accompanied by police violence.

Although homosexuality is not illegal in Peru, same-sex marriage is outlawed across Latin America (see sidebar on p. 89), and there is no antidiscrimination law, let alone any specific legal protection for the transgendered, such as the gender-identity law recently approved in Spain. In Peru, if someone were to see you kissing your same-sex partner in the supermarket, they could call the police and ask you to leave. The only excuse they would need to offer is that “such behavior is not permitted here.”

In the national survey on social exclusion conducted in 2005 by the NGO Women’s Right Defense—Defensa de los Derechos de la Mujer (Demus)—the homosexual community emerged as one of the groups most discriminated against, in a nation riddled with inequalities. Seventy-five percent of Peruvians interviewed said they think it’s “wrong” for two people of the same gender to have sexual contact. And 30 percent still believe homosexuality is a mental illness.

In the midst of that repressive landscape, the trans community has formed its own private ghetto. It even has its own language. They speak “hungarito,” a strange, coded jargon. Vanesa speaks it with her Peruvian friends in Paris. She says it came about as a way of throwing off the police. The words are created by adding syllables and beginning them with the consonants s and r. For example, “heserellosoro gusuruys” means “hello guys!”

As an exercise, try saying, in hungarito, this prayer that I once heard from a transsexual in Lima: “Dear God, make me invisible to the police.”

* * * *

The gynecologist told Amelia that hers was a case of underdeveloped ovaries. She and Melvin would not be able to have children. They wanted a baby so badly they decided to take in an infant whose anonymous mother was going to abort her in a clandestine clinic. A month later, however, Amelia discovered she was pregnant, and they left the “adopted” child in the care of an aunt.

It had taken them months to make love. They lived with Amelia’s mother in her modest house, and they all three slept in the same bed. But one night the mother didn’t come to bed. Amelia escaped to the sofa. Melvin told Amelia that he wanted to sleep with her and he gave her his word as a man that nothing would happen. His word as a man wasn’t worth anything. A couple of gay people had heterosexual sex. Amelia forgot that Melvin was a man with a woman’s body. And that’s why she liked it. Months later, Valery was born.

When Valery was still a baby, Melvin pretended to breastfeed her. After a short while, the little girl was reaching for her dad’s silicone breast. But she knew who was who. Asked to bring Amelia’s shoes over, Valery would reach for the rugged sneakers and not Melvin’s golden high heels. If Amelia put on panties instead of boxer shorts, Valery asked why she’d put on her daddy’s clothes. Melvin would tell Valery that when she grew up, the high heels would be for her. Amelia, for her part, took her daughter to watch neighborhood soccer games.

Valery wasn’t like those children adopted by homosexual couples, children whom the Church considers endangered by the lack of a family. No, she did not have two moms or two dads. She had feminine and masculine role models. She had a dad and a mom. Even though the rest of it was all mixed up.

Amelia believes that Valery will do very well with her dad being a “sissy” and her mom being a “butch.” But she hopes that as an adult she’ll be a feminine girl, for her own good. When she suggests sneakers to Valery, she’s relieved to see Valery choose the heels instead.

* * * *

At her first party in Lima after having her silicone breasts put in, Vanesa remembers watching trannies arrive in their enormous cars, wearing their expensive jewelry and perfumes. She wanted to be like that, exactly like one of those transsexuals that move to Europe and return to Lima like Italian movie divas. How do you do it, she asked them. One said she performed in shows, another that she worked in a discotheque, and another that she married a millionaire. None of them told her the truth.

Going to Milan is, for Peruvian transsexuals, what going to Harvard is for law students. Some leave Peru with false identities, taking advantage of a well-organized network for illegal immigration to Italy, which, according to Vanesa, includes people within the very embassy in Lima. All her friends have gone to Milan: more than two generations of girls who, thanks to sex work, have built genuine mansions for their families in the same poor, marginal neighborhoods where they were raised. In general, they don’t move to the more established, wealthy residential areas of Lima, but opt instead to build second and third floors on existing homes, to install widely recognized status symbols such as Jacuzzis or swimming pools, and to acquire a scandalous, head-turning car. These girls who once were men have been able to pay for costly surgeries to obtain the extraordinarily feminine bodies that are, in turn, the source of their wealth. The sex-change surgery alone might run ten or twelve thousand euros. It is only these impressive amounts of money, and the accompanying transfers back to Peru, that have rehabilitated the image of these exiled transsexuals before those who once so severely judged them.

Felipe Degregori, a Peruvian filmmaker who is working on a documentary about discrimination against transsexuals in Lima, explained the importance to Peruvian transsexuals of money and migration. In the context of the rejection and marginalization they grow up with, sending money home allows them to contribute to the family’s progress, solve their economic problems, and thereby gain the respect of their parents, siblings, neighbors, and even society at large.

“They buy acceptance with money,” Degregori tells me, “so that the families will forget that they’re transvestites, forget that they were once seen as the shame of the family, and come instead to consider them benefactors.”

In Italy a transsexual can make up to 300 or 400 euros a day.

* * * *

“My daughter Georgina thinks that money is what makes class, and that’s not how it is.”

Georgina is another transsexual who has “done well for herself.”

“She has one hundred thousand euros in the bank!” Vanesa shouts at me. Not only has Georgina built her parents their dream house in Peru, she’s also gotten a sex change.

A godmother system operates among Latin American transsexuals. Vanesa is Georgina’s “mother” because she was willing to pay all the costs of the trip to Paris, around five thousand euros—the amount required to get a passport, buy a plane ticket, and settle into a European city. It was a loan, no more, no less. For the “daughter,” it’s the ticket to a dream, and she must work every night to repay her mother’s trust with hard cash. For the mother, the ability to pay for a novice’s trip is a sign of status. The more daughters she flaunts, the more prestige she has in the world of trannies. Vanesa has two daughters in Paris, and is herself the daughter of another transsexual—her namesake—a Vanesa who lives in Milan.

From the beginning her “mother” told her there was only one way to get rich in Milan. She spelled it out: p-u-t-a. You can work as a whore there. The older Vanesa’s eyes shone beneath her false eyelashes. In spite of her advice, Vanesa the namesake was not a whore but a thief. She has lived in Milan since she was sixteen years old and is one of the grand dames of the city’s trans community.

* * * *

On January 14, 2003, Vanesa departed from Jorge Chávez Airport in Lima dressed as a man, as Melvin, with her hair pulled back. She had a fifteen-day tourist visa. She was supposed to get to Italy through France. But she never arrived in Milan. When she disembarked from the Métro in the center of Paris, everything felt familiar. She had a hunch: perhaps she could do it another way. In this city—it was so beautiful—maybe she didn’t have to be a whore. She called her “mother” in Milan, and told her that she couldn’t leave Paris, that she’d pay off the debt from where she was. She got to work cleaning offices.

On one of her first nights in the City of Light, while she was still renting a hotel room, a Peruvian girl took her to the best discotheque on the Champs-Élysées. She approached an older man—a Parisian financial advisor named Alain. “The old man,” as she calls him, took her home. While Vanesa tells me this story I realize that I’m witnessing her personal mythology, her personal paradise lost. For those six months with Alain, Paris was perfect. Vanesa wore Gucci shoes and drove a brand-new car on trips to Disneyland Paris. Back home, she bankrolled a friend’s hair salon and operated on another friend’s nose. She says it that way, as if she had held the scalpel. She sent money to Lima. She visited friends in Milan. “You must get great work in Paris,” they said when they saw her Dior handbag.

In this personal legend, Vanesa is not a whore. She’s a girl with “affectionate friends who help her.” Or at least that’s what she wants me to believe.

“How many women marry for money? How many women are whores and don’t know it?” she asks defensively.

In her anecdotes, she’s always the one who takes care of her parents’ and siblings’ honor and welfare. She dates millionaire men because she likes them, grows fond of them. She plays the role of a beneficent and affectionate kind of daughter to all the older men in her life.

“My friends would say: fag, drop your complexes, work, take advantage of your youth, but I didn’t want to.” But it was becoming more and more clear that she wasn’t going to make it anywhere cleaning offices. Why did her plans change? She arranges one of the curls on her forehead, looking at herself in one of the van windows, and says:

“I fell in love and got fucked.”

* * * *

Melvin’s sister, Carmen, had always known that Melvin was different. Her clothes were always disappearing from her closet, and she knew who was dressing up in them. After a routine appendix operation, the doctor told Melvin’s family that he had an excess of female hormones. The facts didn’t fix anything. Their father would beat him; Melvin would run away.

As an adult, Carmen was so ashamed of her brother that she would leave local parties as soon as he walked through the door. And he wouldn’t keep things private. One day he appeared on a talk show to tell the story of his life. If he was doing it for attention, his father said, he should see a psychologist, and if he was doing it for money, he should get a job.

Carmen, who sees Melvin and Amelia’s daughter, Valery, once in a while, says her niece is affected. She worries because the girl is growing up in an environment she considers inadequate. Carmen says Amelia abandons the girl to an elderly grandmother, and now Valery is too thin, speaks in slang, and—worse—has her mother’s boy-short hair.

According to Carmen, the little girl always asks why her dad wears high heels and why he puts lipstick on his mouth.

It’s because he’s a clown, she answers. He’s always wearing costumes.

* * * *

We get off the Métro at the quartier Jean Jaurès stop, a few steps from Vanesa’s apartment on avenue Secrétan, next to the northern station and the canal de l’Ourcq.

“Let’s buy something to eat, because I don’t have anything.”

Vanesa enters Dia, a Spanish-owned supermarket chain with an air of decay. Rumor has it you shouldn’t buy vegetables, fruit, or meat there. You have to stick to packaged items. Vanesa fills her basket with potatoes, milk, and Coca-Cola.

All kinds of people live in Vanesa’s neighborhood, mostly middle-class people. A group of homosexuals stakes a place beside the canal for the night. Vanesa mentions this to me as if she were a gossipy neighbor and this were a strange phenomenon instead of a part of her life. She tells me that soon I’ll see the apartment, that it’s small but has a great advantage: she doesn’t pay anything for it. She rented it with nothing but her passport, and one day she stopped paying. Months went by, and the owner took her to court but got charged himself for doing business with illegals. If Vanesa wins the case, she may even be able to keep the apartment.

In reality, Vanesa’s place is only a one-room studio, about 150 square feet. I’m immediately struck by the smell. How can it smell like Lima in Paris? More specifically, like certain houses in Lima, at certain times of the day. A mix of dirty clothes, and food stewed in water with rice and garlic. The heater is up all the way. It’s almost hot. It’s always on. The cat Chinchosa (“hated one,” in Lima’s slang) sleeps on one of the radiators. Two Australian parakeets squawk noisily. The decorations are baroque and seem as if they just came out of shipping boxes. There’s an old, round table in front of a gigantic television. A threadbare sofa. A picture of a man on a sleigh crossing a snowy landscape. A bed at the far end, and, on the wall, some palm leaves oddly arranged around a large portrait of Vanesa, as if it were a print of the Virgin. Adornments include Dalmatian figurines and vases full of old keys, buttons, one-cent coins arranged haphazardly. Disparate accessories hang from nails on the wall, such as a feather boa and a Mickey Mouse Sorcerer’s Apprentice hat. On the fridge, there are photos of Vanesa posing with other transsexual girls and a photo of a guy with a little girl. The child, who in the photo is probably about four years old, smiles mischievously and makes the hand gesture used in Peru to refer to homosexuals: a circle made by touching the index finger and thumb.

I’m struck by a kind of makeshift bedroom with sheets for doors. Frederic, the husband, is sleeping in there. I can’t see him. I can only hear him snore and let out a fart. Vanesa holds back her laughter.

“¡Uy, Papi! Look how you’re sleeping. Get up already. The thing is, yesterday we went to a party and got home at six in the morning.”

I start to feel uncomfortable. I’m sharing a room, all night, with a transsexual and her snoring husband.

“I met Frederic three days after he got out of jail,” Vanesa says as she fills the fridge.

Frederic, Parisian by birth, was detained in Rome with several kilos of Brazilian cocaine, and spent five years in prison. Vanesa tells me that his girlfriend at the time, a Brazilian prostitute, used him for drugs. When he was freed, the first thing he did was look up some prostitutes he’d been a frequent client of, who lived on this same floor and who happened to be friends of Vanesa’s. He stopped by, but instead of sex, the two of them ended up talking until the sun came up. “Do you like fried eggs?”

She prepares two eggs for me and we eat them with Coca-Cola and buttered bread. A breakfast with limeño charm.

“That’s why I can’t marry him, see. Girl, if I could, I’d already have papers. Uy, imagine if we got married. Me, a Peruvian, and married to an ex-narco. They’d search me from head to toe in all the airports.”

She shows me some photos. In one of them a blond guy appears.

“That one wanted to marry me, but only because he thought I was a woman.”

When she told him the truth it was a shock.

“He told me he thought he’d found the woman to marry and have children with. I told him: I have children. But he left me.”

She takes out another photo: Vanesa and Frederic and his family at a picnic. They look very happy. They know she’s gay and they accept her. Frederic, in the photo, is almost two meters tall, a bald, burly man.

“He’s a good guy but he’s worn down. There are days when he doesn’t even give me a euro, but I’m not interested in money.”

Frederic had been a bus driver before being injured in a car accident. He was driving at 200 kilometers an hour. When they found him, his leg was behind his head. Now he has nails in his bones and receives a monthly pension of 300 euros, which doesn’t pay for very much.

“The good thing is that he cleans, washes clothes, and cooks and does it with five euros.”

* * * *

“Good morning.”

Frederic comes out in his boxer shorts and undershirt.

“Hey, shithead, you’ve slept like a pig.”

I soon realize that the swearwords are actually affectionate endearments. Frederic shouts from the kitchen, accusingly. “Vanesa, what about the chicken?”

“It’s out here.”

“But you haven’t boiled it yet. It takes an hour.”

The man of the house speaks a highly individual mix of French, Italian, and Portuguese. Only because of the Latin root can we understand each other in Spanish.

“I’m saying to you, my love, my love, get up. I’ve let you sleep so you won’t be in a bad mood. Come on, go to the kitchen to cook and don’t bug me.”

For a second I don’t know which one of them is the dominant male of the house. In any case, it seems like a pretty equal power struggle. I start to feel like the only woman in the room. I start to feel very alone.

“And have you fed the cat?”

The Frenchman knows how to swear in perfect Peruvian dialect: conchatumadre, your mother’s cunt, he says.

“Yes, he’s already eaten.”

The cat is his.

Frederic serves himself a Coca-Cola in silence.

“This man stresses me out, I swear,” says Vanesa.

I realize I’m going to spend the next forty-eight hours with a couple on the brink of nervous breakdowns or a wrestling match, so I may as well start to make conversation. Just to be safe, I ask Frederic something I already know: how he met Vanesa.

“Here in this house when …”

“I already told her, shut up.”

“You’re not very affectionate, are you, Vanesa?” I ask, unable to help it.

“I’m very affectionate,” Frederic says in Spanish, “but he isn’t.”

He uses the Spanish word él for “he,” and I remember the word for “she” in French, elle, is pronounced the same way.

Vanesa is a woman trapped in the body of a man. But according to Frederic, she’s actually a guy hiding in the (false) body of a woman.

* * * *

When Vanesa lived her previous life as a man named Melvin, she worked as a conductor on one of those minivans that function as public transportation in Lima. She was taking classes at Universidad de San Martín, training for a career in hotel management and tourism. When she quit to become a woman, her father couldn’t understand the obsession with dressing as a woman. If Melvin wanted, he could be gay, but there was no reason to create a public scandal. He knew tons of people from work who were homosexual. They lived one life at home and another on the street.

For her father, Vanesa cut her hair, crying.

For Valery, her own daughter, she traveled to Europe as a whore.

* * * *

I have a headache, and possibly a fever. I need to go to the bathroom and use my breast pump immediately, or I run the risk of infection. Over Vanesa’s bathtub I extract several cubic centimeters of milk with my hands, because the breast pump isn’t cooperating. Nature can be very cruel. Right now I feel as though I’d give it all up for silicone tits, to get rid of my troublesome feminine condition. Vanesa, meanwhile, is changing her shirt. Her almost-perfect tits are in full view, and I can’t help making comparisons. Curiosity is killing me and I ask whether I can touch them.

“Of course!”

“I don’t feel anything strange …”

“They’re normal, see? They can even press together.”

“There’s something sort of hard in the back but they’re quite soft, they seem natural …”

“Yes, I was lucky.”

“They never grow old. They’re better than the real ones …”

“Normally they sag.”

“Oh, so they sag, too …”

“I’ve got a friend who looks like she’s had five puppies and six kittens and four little pigs. But mine don’t sag, I don’t know why.”

“What do you do?”

“Nothing. They say they can break, but I’ve been in fistfights, and nothing.”

Vanesa’s medical procedures are numerous: nose, saline serum prosthesis in her breasts, and many hormones. She once injected silicone into her own hips because the operation was so expensive. She bought needles at the pharmacy and locked herself into a hotel room. She filled each hole in her masculine body with that greasy liquid and a feminine curvature instantly appeared. The tits, on the other hand, were operated on by a Peruvian surgeon for twelve hundred American dollars.

“And I didn’t finish paying for them. I only gave him 700 dollars. He told me to bring the rest of the money when I came back to have the stitches removed. I never went back. I took the stitches out with nail clippers.”

Vanesa likes herself. She’s an almost unbearable narcissist. Her vanity surpasses that of all the women I know. She talks about her body and congratulates herself for her good fortune. Thanks to her delicate bones, she’s been able to design a body very similar to a twentysomething girl’s. Nothing like those transsexuals with coarse, vulgar curves.

Still, she says she doesn’t have a sex change in mind.

“A friend of mine had a clitoris made out of the head of her penis. She says she feels like she comes, but doesn’t ejaculate. And I have another friend who says she doesn’t feel anything, even when pissing. She says ‘Stick it in’ to her husband and he goes: ‘But it’s already in.’ I’ll always be a man. I can’t take the place of a woman even if I’m operated on. I’m already going against God being the way I am. Imagine if I were to operate. I would have liked to have been born a woman, but it just couldn’t be that way.”

We go out for a walk around the neighborhood. We enter a phone booth. And as we watch all kinds of men go by as if on a television screen, she tells me a simpler and more cynical truth: “I’m not getting the operation because, if I do, I won’t get business. I’ll operate when I can’t get it up anymore.”

* * * *

When I mention Valery’s mother, Amelia, in front of Frederic, he says, “Ah! Michael, Vanesa’s woman.” It’s been a month since they’ve heard from her. According to Vanesa, Amelia has been getting drunk with the money she was sending for their daughter. Vanesa tells me they’ll always be a family, but that she doesn’t like Amelia’s attitude at all.

“It’s not that I’m sexist, but if I offer her protection I want her to value it. I asked her not to fail me and she did.”

When they separated, Vanesa told Michael that if one day their love ended he would always have her support.

“Now Amelia’s gone off with a prostitute, and I’m not jealous. She called and told me. I’ve just asked her to take care of herself.”

“Maybe she was drinking because she missed you …”

“Do you know how much I spent on talking to her on the phone? Eight hundred euros, paid for by my old man. I called her from one until five in the morning. I’d put songs on and we’d cry all night.”

* * * *

In the photo, Amelia is six years old. Her mother has put her in a white dress and tied bows in her long hair. It’s her baptism.

At eleven years old, she only wants to wear sports pants to school. When her mother asks her where the skirt of her uniform is, she always says it’s in the wash. She plays soccer, changes her name to Michael. She likes being around men, so that she can learn from them, to imitate their clothing, their conversation. She only falls in love with girls.

One day, her mother finally accepts that her daughter is not like other girls, that she will grow up to look like a man. In Lima, they call women like her “Chitos”—bull-dykes. When Amelia, against all odds, became involved with a man, her mother was ecstatic. The fact that the man was Vanesa couldn’t interfere with her relief.

* * * *

Infection has occurred. My temperature must be above one hundred degrees. My breasts are like two river stones.

Vanesa sleeps. We’re resting after eating the chicken stew Frederic prepared. I’ve gone into the bathroom hourly to milk myself, but it’s not enough. I need to go to a hospital to get an electric breast pump that can extract large quantities of milk and alleviate the pain, but Vanesa refuses to accompany me. She turns into a willful, inconsiderate child when someone tries to separate her from her bed. Instead, Frederic offers to come with me. We walk to the maternity wing, and somehow they don’t have a breast pump. They recommend that I keep pumping my breasts with my hand. When we get back to the apartment Vanesa tells me sleepily that this happened to Michael, too, when he was breastfeeding Valery. She teaches me how to squeeze them.

Tonight Frederic and Vanesa are taking me to the Forest. Bois de Boulogne is a park at the western edge of Paris, near the suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. It is more than three square miles—two and a half times larger than New York’s Central Park. During the Hundred Years War, the forest was a hideout for outlaws. Henry IV planted fifteen thousand mulberry trees in hopes of igniting the local silk industry. His repudiated wife, Marguerite de Valois, took refuge there. The place was transformed into a park by Napoleon III in 1852. The Parisians called it the Garden of Earthly Delights, but, like the Bosch painting, it’s no paradise, and is more often a hell for twisted souls. Robert Bresson made a film called Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. The Bois gave shelter to close to fifteen hundred sex workers of both sexes, but a few years ago a “cleanup” was carried out and now there are only a few women and several hundred transsexuals left, most of them undocumented immigrants from Latin America.

* * * *

Although she hasn’t told me this explicitly, Vanesa works as a prostitute. At first she tries to make me believe that she’s going to the Forest just for tonight, to get some euros. But she has an ad on a website with her phone number. She gets a routine phone call from someone requesting “psychological and physical domination.” When clients come to this house, she can charge them up to 150 euros to have sex in the bed where, she informs me, I’m going to sleep tonight. But it’s simpler to go to the Forest; there she makes thirty euros per client but the flow is constant and sometimes the clients are more than generous.

“I did theater for children, I danced in cabarets, I wanted to prove that transvestites don’t just come to Europe to go whoring, but, as they say, it didn’t work out that way.”

Frederic tells me that he is not a prejudiced person, that he loves without caring whether the object of that affection is a man or a whore or both things at once. Before handing his girlfriend over to all the city’s vices, he prepares her a delicious bubble bath that she rejects very crankily.

“I’ve told you a thousand times not to put foam in.”

“You think I’m your slave?”

“Oh yeah, you’re real macho!”

It’s my first time going out with a whore. Vanesa puts on tight pants and a short top. The cold is tremendous tonight in Paris—in the Forest, they tell me, it drops to zero degrees. Vanesa wears no coat.

“I’d rather die from the cold than die of hunger,” she says.

We get into Frederic’s rickety car. Vanesa’s husband knows the world of Parisian sex work inside out. He’s had two prior partners who were prostitutes. He tells me that he’s worked as a clandestine taxi driver for transsexual girls for quite some time, though right now he’s unemployed. He used to pick them up at their homes and charge them ten euros to take them to the neighborhoods around the Forest. I notice that the car’s windshield is broken. I conclude that the Frenchman doesn’t learn his lessons and still drives at illegal speeds. He manages to run all the traffic lights.

“Did Lady Di die around here?” I joke, but they only respond that the place I’ve mentioned is far from the Forest.

I can see the headlines: narco, trannie, and journalist crash on way to forest of the whores.

“The folks who go to the Forest want to know what you’ve got between your legs.” Vanesa has a knack for gritty Latin American realism. In one sentence, she routinely draws me right out of any self-pitying contemplations and back into her living world. “Some of them think you’re a woman, but when they discover that you’re not they don’t care. In fact, they get even more into it. Their fantasy is to tell me it’s their first time and ask me if they can touch it, if they can see it. Then they’re on their knees. To each their drama.”

Vanesa can be very vulgar, but her fantasy is to be treated like a dainty girl. To each their drama.

* * * *

Michael knew Vanesa had fallen in love with someone else and that she planned to stay in Paris. He felt alone and found another partner to ease his suffering. Now he and little Valery live with the new partner. Despite his looks, he’s still one of those girls who talk about being very much in love.

Sometimes Valery looks at photos of Vanesa and says: “My dad is very pretty.”

According to Michael, Vanesa hasn’t sent money for her daughter in more than a year. And even when she did send money, there were many months when nothing came. Michael knows Vanesa has had problems but he needs the help more than ever. He works sealing bags in the central market, sometimes on graveyard shift. If he gets home before eight he just has time to take Valery to school.

Despite the hardships, it looks as if everything has returned to a kind of normality: Melvin is with a guy and Amelia is with a girl. Vanesa has her man and Michael has his woman.

* * * *

We enter the Forest as though it’s another world, dark, gloomy, and deep with all kinds of sexual fantasies. Once my eyes adjust I can see human figures everywhere, looking supernatural in their wigs and coats. The glint of glitter and metallic boots shines through the trees. All kinds of things happen here. One time, a guy asked Vanesa to tie him up and the police arrived suddenly. She ran off and left him there, still in bondage. One night they found a fellow prostitute stabbed, and another was taken to the hospital in a coma. How it goes for you depends on whom you’re with. Vanesa topples some stereotypes tonight: she tells me that in the Forest, Arabs insult the trannies but then want to be penetrated by them. She says there are many black men who have a small one, and that there are Algerian transsexuals. You have to prepare yourself for the unexpected.

Frederic leaves us at the Peruvians’ meeting place. There we find two compatriots at rest, eating Chinese food that was sold to them right in the Forest. One of them is Tatiana, Vanesa’s adopted daughter. They’re talking about a female hairdresser, a former kindergarten teacher. Tatiana took her into her house where she supposedly came on to Tatiana’s husband, whom she surely met in the Forest.

“The new arrivals always want to achieve, in a short while, what has taken time and effort for the rest of us,” maintains Betina, the oldest of the group. Her disillusioned attitude contrasts with the enthusiasm of a young Brazilian who lets out an ear-splitting shout: “I’m a woman, I’m a woman!”

“She’s always mistaken for a trannie,” Vanesa explains.

The small carioca opens her coat against the wind. Headlights pool against her bare breasts and diminutive bikini bottom. For an instant in the moonlight she’s the carved prow of a boat adrift. She lowers her bikini bottom, spreads the bush of hair, and proudly shows us all what a natural woman looks like. She runs a finger over herself and licks it, as if in a pornographic movie. Without a doubt she must be under the influence of some magnificent drug. In the Forest, it’s common for some girls to drug themselves to withstand the cold and the hours of hard work.

“Vanesa has a pretty body and, since she’s small, she can pass as a woman. The Brazilian, on the other hand, is a woman but acts like a trannie. You don’t have to be a woman to be feminine.”

Betina is a fount of wisdom.

“And the Brazilian is a nymphomaniac,” adds Tatiana.

I see Vanesa, with all her fabricated femininity, move away toward the cars that are lining up to admire her. If she stayed with us, she wouldn’t be able to work. Mostly because Frederic has just returned, with the intimidating air of a pimp.

At that moment an old Peugeot pulls up beside us. There’s a woman inside. She’s Frederic’s sister, who has temporarily inherited the clandestine taxi business. Frederic invites me into her car for a lightning tour of the forest while we wait for Vanesa to do what she has to do. I’m the sister’s copilot. A large woman with glasses by the name of Florence, who wears an alpaca poncho, a gift from one of the Peruvian girls.

“Hi, Carolina. Say hello to your husband,” Frederic says to a tall, dark-skinned woman who shivers with cold next to the highway.

Frederic is friends with all of them. He calls to them from the car, explaining who’s who to me. In this forest I’ve found a mini Latin America—a microcosm of our continent. This one’s Argentinean. This one’s Peruvian, but she has Spanish papers. That was the one they found with her head cut open. They call this one Ñata and she makes a delicious ceviche.

I keep my eye on Frederic’s sister. Florence went though a period of depression and her weight went up to 265 pounds, Frederic explains to me. Now she’s lost 80 pounds and she’s trying to get out, earning her living in this way.

The ones with the wigs are Arab transsexuals. That one walking over there is the Ecuadorian who sells food. And that one is Paloma; she was a cop in Peru. Farther off is Shirley, another Peruvian who studied at the university and is very intelligent.

There are fifteen or twenty people in Ecuador living off what that girl standing there does with her ass every night in the Forest.

And that one heading over here has AIDS, but she takes care of her clients. Because she’s sick, the French government gives her food, shelter, medicine, and even papers.

According to the Parisian organization Prevention, Action, Health, Work for Transgender People (the French acronym is PASTT), which works with the girls of the Forest, there are hundreds of letters requesting residency, housing, and legal assistance with immigration papers, as the majority of trans people in this situation are foreigners. Hardly any letters are answered.

I feel invisible among the perfectly doctored bodies of the sex workers, with my five-foot-seven frame and my unremarkable measurements. At wrestling matches or action movies the same insecurities must assail men. A transsexual is no more than the projection of what a man believes a woman to be. Maybe that’s why heterosexual men like transsexuals so much: in these times, they are the closest approximation of the illusory feminine ideal.

Florence has to drop us off. Frederic and I walk, looking for Vanesa, who’s been lost for more than an hour.

“A pretty strange life, don’t you think?” Frederic says.

“Strange?”

“A shit life.”

* * * *

It’s below freezing, and I’ve got a high fever. Frederic walks the way he drives. He makes me cross a dangerous intersection while the light is red. Again, my breasts are at the point of bursting.

Not too long ago, Vanesa was picked up in the Forest by the police. For being transsexual, a whore, and illegal. Almost nothing. All she had to do was say she was Cuban—fags were killed in her country every day. She was released. When she left jail, she called Peru in search of solace but they only wanted to know when she would send them money. That’s why she changed her phone number. That’s why it was hard to get a hold of her.

She’s left behind the glory days when she cross-dressed as guardian angel for her trannie sisters. Now she’s in love with that easygoing, intelligent chulo who prepares her bubble baths and treats her like a spoiled child.

Vanesa comes out of the Forest looking like a bruised fairy. She’s made ninety euros in an hour. Just now, she’s dropped a ten-euro bill somewhere in the park, and she’s annoyed.

Before arriving home, we stop in a store and, with the money she’s earned, we buy bread, ham, cheese, butter, cookies, and chocolate. They want to treat me. Then, we take refuge in their den, where we blast the heater and eat together, almost happy. I remember that Frederic also has children far away—as Vanesa does, and I, too, if only for tonight. He told me about them a few hours ago, walking to the maternity ward. Their mother took them to Brazil, and he hasn’t seen them since. We’re all far from our children right now. When these two are alone in the bed where they will never be able to procreate, do they think of these estranged children? Of Valery, for example. I let a little more milk go down the drain while I take a hot shower. According to the girls of the Forest, they always shower when they get home to make themselves feel better. In the bed where Vanesa sometimes earns her living, I sleep on my coat.