Is there such a thing as an easy situation with William Faulkner? His name is synonymous with complexity. It pervades his style, his storylines, and the format of his novels. Interacting with the public, the man obfuscated, exaggerated, and misled. Scholars and readers alike would agree that there’s nothing simple or straightforward about Faulkner or his work.

Such is the case with Sanctuary. It is a much debated and studied book. A story of big-city scandal, it is atypical of canonical Faulkner works and generally not considered among his finest. This thinking began with the man himself, who claimed to have written the novel in three weeks, casting an air of carelessness around it and asserting to have done so for money, rather than for the more literary motives of art and legacy. Eventually, scholars caught up to his bluff, showing that not only did Faulkner spend months on the Sanctuary manuscript, he also painstakingly rewrote it and spent more money to revise its galleys than he’d received in an advance on the book. Still, it suffers the stepchild’s fate.

Truly, I don’t care about delineating the high marks of Faulkner’s canon or otherwise participating in scholarly discourse around him. I came to Faulkner, not because of his mystique or his following, but because of Memphis, Tennessee.

To back up a little, I initially read Faulkner more than a decade ago as a graduate-school assignment: Absalom, Absalom! At the time, I had no background in Mississippi history or Faulkner. I had never heard of wisteria. I had no idea what the hell was going on. I did, however, catch the aura of the literary following projected around him, a sort of high-school, cool-kids-against-nerds exclusivity, writ nerdy. You either get Faulkner or you don’t. I pretended to get it. The prospect of having to pack so much historical equipment on your journey into Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha has proven endlessly fascinating for his legions of followers. The same baggage casts an air of tediousness around the whole enterprise of Faulkner and Faulkneria for outsiders.

By the time I heard about Sanctuary, I had spent years researching the Memphis red-light district for a book I was working on. Unlike Storyville in New Orleans and Chicago’s Levee, the Memphis underworld has no tawdry memoirs to speak for it and is not nearly as well-remembered or widely renowned as its counterparts from the Bowery to the Barbary Coast. I grinded through decades of city directories, property deeds, fire-insurance maps, census data, court cases, newspapers, and wills. A few oral histories lent color. Gradually, the red-light-district geography and its cast of characters became clear. The district grew around Beale Street, on parallel and intersecting boulevards. None of it remains today, but in just a few blocks, almost overlapping respectable downtown businesses and posh residences, mayhem ruled for the better part of a century.

Through my research, I got to know long-dead madams. They had been widows and divorcées in a man’s world, generous and loyal to their families, typically Catholic, most overweight and gaudily attired. Brothel ownership belonged to a few of them, but also to many prominent citizens as well. Their employees danced the cancan on front porches, rode horseback naked through the streets, and made daring, sometimes violent escapes from this life of involuntary entry.

Saloons fell under the control of politically protected gangsters. In this history, I saw the rules of law, race, class, gender, and morality get pushed off a brothel roof and smashed on the cobblestones below. I found one instance of a white man from a prominent family who passed as black and spent ten years in the late nineteenth century as a gambler and pimp in this alternate universe. I began to see Memphis as a city of untold stories.

So I cracked Sanctuary—and it is both compelling and shocking. A Mississippi debutante ends up whoring in a Memphis brothel after witnessing a murder in a backwoods corncrib. She supposedly was violated with a corncob. She has to testify in the trial of the murder, and the corncob gets introduced as evidence. This, from a future Nobel Laureate and subject of countless pretentious conversations and scholarly studies. It just about peeled the leather elbow patches off my tweed jacket. Though Sanctuary capitalizes on outrageousness, I can’t call it implausible.

I started to feel like he’d written this book for me. I could read between Faulkner’s lines to a much deeper truth behind the story. I felt the same sociological, moral, and historical undercurrents throughout Sanctuary that I’d reassembled in my research. I finally reached the same conclusion about Faulkner that you’ve already heard—he’s a damn genius.

The two towering figures over Faulkner’s Memphis never appear in Sanctuary, yet they are present. In life they were nothing short of—I hate to say it—Faulknerian. They are the architect of the red-light district and a man who became its lord. Both hailed from a town well known to Faulkner-philes: Holly Springs, Mississippi, right across the county line from Lafayette, the real-life model for Faulkner’s legendary Yoknapatawpha county. The architect was Robert Church, and the lord was Edward Hull “Boss” Crump.

According to biographer Joseph Blotner, between fall 1920 and fall 1921, Faulkner and his pal Phil Stone regularly trekked the seventy or so miles from Oxford, Mississippi, to Memphis and gallivanted through the big city’s underworld. They gambled and boozed in city-sanctioned nightclub casinos, and they visited what were among the last old-fashioned parlor whorehouses in the country, since Storyville and the Levee had closed. Here, as a survey of commercialized vice in Memphis would explain, a maid answered the door, welcomed the guests inside, and called all the residents to greet and mingle with the company. This represented a civilized version of the ancient transaction, as the callers then purchased intoxicating beverages and visited before making their selections and heading upstairs. Blotner claims that Faulkner, poor as a church mouse and not much better dressed, never went upstairs, and even when a girl propositioned him, he played the gigolo at rest, quipping, “No thank you, ma’am, I’m on my vacation.”

Instead, he stayed in the parlor and imbibed the atmosphere, the wine, and the stories. In an early version of Sanctuary, he would chillingly evoke the moment the girls came downstairs—“But there was something about her, something of that abject arrogance, that mixture of arrogance and cringing beneath all the lace and scent which he had felt when the inmates of brothels entered the parlor in the formal parade of shrill identical smiles….”

He excised the line from the published text, however, opting to keep his male lead, Horace Benbow, “he” from the quote, clean of such experience.

In the parlor, Faulkner tapped into a history as rich and complex as that of his native Mississippi.

That history grew out of seismic community trauma, when the world started over after the Civil War. The war hadn’t treated Memphis too roughly—Union victory in a naval conflict on the Mississippi on June 6, 1862, put the city under federal control, sparing the place from the fates suffered in Atlanta and Richmond, Virginia. Though functionally intact, war left the city’s cultural fabric shredded. With much of their economy connected to cotton, Memphians had overwhelmingly supported secession before the war, but after the city’s fall its population swelled, mostly with Negroes from the surrounding countryside, plus a few carpetbaggers from up North. Transplanted Yankees edited newspapers, launched businesses, and held public office. They set up the local Freedmen’s Bureau and the Freedmen’s Bank, to help establish former slaves in normal society, plus black schools and churches. And of course, Union soldiers staffed Fort Pickering. Some military men were Northern whites. Many, however, were the most egregious and hated manifestation of the new world order, colored soldiers. Their presence—armed, patrolling the streets, and empowered to tell white people what to do—caused severe outrage among secessionist citizens and newspaper editors, who howled to no avail for the Negro patrols to cease. The black soldiers’ opposites on the street were the city policemen, many of whom were Confederate veterans. Shouting matches and fistfights between the soldiers and police erupted into a riot on May 1, 1866.

The riot would set the moral tone for the new nation and determine its racial geography.

The blood orgy lasted three days. Afterward, no one could deny the obvious disparity between forty-six dead black people, many of them soldiers in blue, and only two dead white people. Even the most ardent fire-eating newspapers—the same ones that circulated rumors of Negro uprising to start the riot—expressed disgust at the unnecessary destruction of black churches and schools.

The white rioters had taken more than life and property. A congressional committee that came to investigate the riot heard testimony from several black females, one of whom recalled that four white men, one in police uniform, broke into her house. One held a knife to her throat. “I just had to give up to them,” she said. “They said they would kill me if I did not. They put me on the bed, and the other men were plundering the house while this man was carrying on.”

Another African-American woman testified that a policeman named Dunn had invaded her home with another man, barred the door behind them, and raped her. “Mr. Dunn had to do with me twice,” she said, “and the other gentleman once. And then Mr. Dunn tried to make me suck him. I cried. He asked me what I was crying about, and tried to make me suck it.”

Meanwhile, a police gang attacked a black saloon. They broke down the door, looted the register, emptied the liquor barrels into their stomachs and onto the floor, and shot the owner in the neck and head, leaving him for dead. He was twenty-seven-year-old Robert Church.

But Church was much more than just another Negro—he was the son of a revered white man.

Like many other Memphis citizens of color, Church appeared before the congressional committee that came to investigate the riot. He was asked, “How much of a colored man are you?”

Church replied, “I do not know—very little. My father is a white man. My mother is as white as I am. Captain Church is my father.”

The issue wrapped up in that question—How much of a colored man are you—complicated his public identity. Was he to be treated as a Negro, or enjoy the advantages of his white aristocratic blood?

Church immersed himself in this gray area. He became something of a postwar profiteer off the city’s new order. With his powerful connections to the city elite, thanks to his father, and his own guile and vision, Church expanded a brothel or two into a full, first-class red-light district on Gayoso Street. Not only that, after the riot instilled a sense of segregation for safety in black Memphis, he developed the most vital black neighborhood in the country one block south of Gayoso on iconic Beale Street.

Church suffered from his riot wounds for the rest of his life. A bullet hole in his skull never healed, and severe migraines immobilized him at times. This didn’t prevent him from enacting a potent and visionary revenge. After white men destroyed black Memphis and raped black women during the riot, Church, a man who began his life in slavery and became known as “the South’s first black millionaire,” financed Beale, Main Street of Black America, through white women working in his brothels.

“A man by the name of Robert Church had opened up a whole bunch of these houses, they all looked alike, on Gayoso,” district resident Frank Liberto told Memphis journalist Margaret McKee in 1973. “Well they were built a little bit like the old houses you see in Baltimore. Right next to each other. No yard, no nothing. Just a porch with a brass rail…they were just like mansions, I guess, inside. They was some of them had mirrors all around the rooms, the bedrooms…”

Liberto remembered the women as well. “Well, some of them were the prettiest women I guess that you could find anywhere. They were gorgeous. The ones that used to sit out on the front porches during summertime, they were just beautiful women. I don’t know where they all come from. I would say that most of them came from these small towns [in] Mississippi, Arkansas.”

Church’s prominence brought ambiguity to the otherwise rigid rules of race in Memphis. Hell, he exposed the basic tenets of white supremacy as frauds—black and white were supposed to be separate. White men were supposed to protect their women and female honor. Church capitalized on the lie.

This all had become a matter of public record, local lore, and brothel-parlor gossip by the time Faulkner visited one of the brownstones on Gayoso Street.

By then, Robert Church Sr. had died and made his son kingpin, while white political leader “Boss” Crump was building a political machine that would become equal in notoriety and of comparable influence to the organizations of Huey Long in Louisiana or Tammany Hall in New York.

Memphis voters elected Crump mayor in 1909, but an ouster suit on charges alleging Crump’s ownership of property used for immoral purposes, among other things, prompted his removal from office in 1915. From that experience, Crump developed a role in which he held power without ever subjecting himself to democratic process. The office of “boss” never appeared on any ballot, but Crump would hold it until his death in 1954.

Crump controlled the city and county offices, the state legislature, and a seat in Congress, and he enjoyed considerable sway both with the governor and one of the state’s US senators — whomever held each office usually owed his victory to Crump.

Crump built this machine and maintained it, partially, with financial resources and political support generated in the underworld. Crump rule meant wide-open, regulated vice. Madams donated money to the machine war chest and submitted to routine arrests and financial forfeitures through the criminal-court system, “paying for the privilege,” as the custom had been known since the Civil War. Their bawds all submitted to regular gynecological examination and posted results in their rooms. As a Memphis prostitute told an interviewer in 1938, “A man don’t run no chances when he lays a girl in a house. You see, the law makes us all get examined. No landlady will let a girl hustle until she’s been to the doctor. We go twice a month for a smear and once a month for a blood test. If the doctor finds us OK, he sends a report to the city doctor and we can work.”

They registered to vote, and voted right. “One thing we have to do is pay our poll tax when we vote,” another prostitute said. “The landladies see to that…She’ll tell us [who to vote for] before we go. She knows because she votes plenty often.”

Likewise, gamblers earned sanction from the machine, offering in exchange political donations, election assistance, and acquiescence to criminal round-ups for the benefit of the square public. Thus, madams could operate a business everyone knew was illegal, in a place anyone could find her at any time. Gamblers such as Bob Berryman and Reno DeVaux operated casinos in the same open manner one would need to run a café, though in flagrant defiance of the law.

Bootleggers like “Cap” Laughter, Berryman, and “Red Lawrence,” among others, transported booze by river or road through town. Should a federal agent have apprehended one of these fellows on a booze run from upriver in Saint Louis, downriver in New Orleans, or across statelines in Kentucky, as the hottest routes went, they’d be on their own, but in the city, they didn’t have to worry about the feds—Crump’s friends in the US House and Senate ensured friendly appointments to the local Prohibition office.

Policemen operated graft rackets and put non-sanctioned criminals out of business or out of town. They caught one of Al Capone’s brothers coming through the red-light district in 1928, they threw him in jail overnight, and showed him the way back to Chicago the next day. This, and other acts like it, gave the all-important public impression that local lawmen were fighting crime.

Crump controlled the city attorney and county attorney general, while the federal DA and judges were locals who deferred to local authority on serious criminal matters.

By 1929, when Faulkner began writing Sanctuary, Crump stood at the pinnacle of his power. Faulkner had to approach the subject of Memphis under machine rule with caution. In what might be deemed classic Faulkner, he illuminated ever-present, unseen forces through the people these forces acted upon. He assailed the machine indirectly, focusing instead on the human toll of Crump’s municipal dictatorship, its hypocrisy and corruption. Sanctuary is a stinging indictment of unnamed crooks. This is what Faulkner does.

While writing Sanctuary, the author clearly reflected on his brothel-parlor conversations. One tale still going around when Faulkner visited had gone down in October 1916, when a four-and-a-half-fingered jewel thief murdered a madam and left his distinctive bloody handprint at the scene. The slain madam went by the name Mae Goodwin. Faulkner named Sanctuary’s doomed bootlegger Lee Goodwin.

Mocking, as directly as he could, the Crump organization’s progressive-reform veneer, Faulkner named madam Reba Rivers’s lap dog “Mr. Binford,” a salute to the head of the Memphis board of censors, Lloyd T. Binford. The censor would ban Charlie Chaplin films from Memphis because of the actor’s disreputable character and ban “Our Gang” films for suggesting social equality between the races in their integrated schoolrooms.

Madam Reba explains her familiarity with Memphis officialdom: “I’ve had two police captains drinking beer in my dining-room and the commissioner himself upstairs with one of my girls.” This trend echoed in the remarks of a Memphis prostitute quoted in a 1938 survey of the city’s vice industry. “[T]he law is mighty fine in this town,” she said. “They never bother us at all. They come in, sit around, drink, dance, and even get laid.”

Faulkner also flashed his keen sense of tenderloin direction in Sanctuary, navigating characters through the racially organized neighborhood of whorehouses to the colored girls. As Frank Liberto recalled in the seventies, “They had a red light district on Hadden Avenue, they was nothing but colored and what they called Creoles.” In Sanctuary, a trio of Mississippi boys “crossed a street of negro stores and theatres”—Beale—“and turned into a narrow, dark street”—Hadden—“and stopped at a house with red shades in the lighted windows.”

They could hear music inside, and shrill voices, and feet. They were admitted into a bare hallway where two shabby negro men argues with a drunk white man in greasy overalls. Through an open door they saw a room filled with coffee-colored women in bright dresses, with ornate hair and golden smiles.

“Them’s niggers,” Virgil said.

“Course they’re niggers,” Clarence said. “But see this?” He waved a banknote…“This stuff is color-blind.”

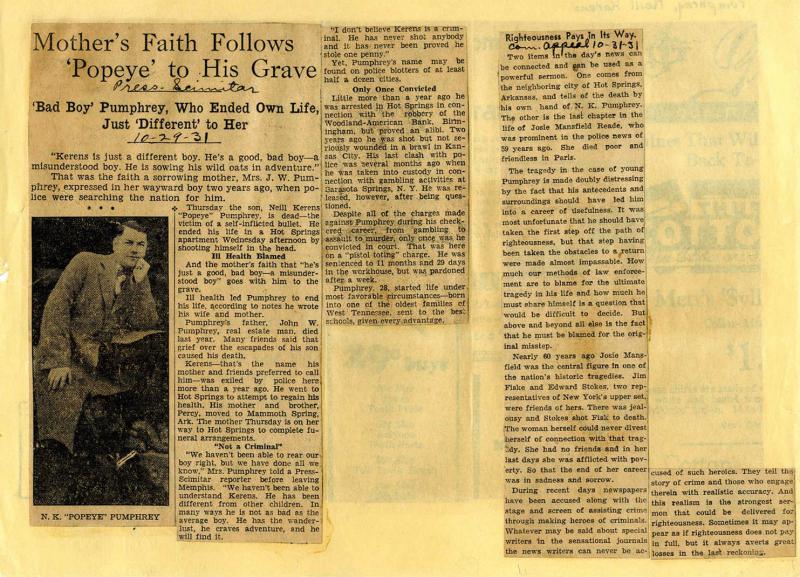

Finally, the most important Sanctuary tribute to Memphis’s real-life underworld appeared in the form of lead villain “Popeye.” Neil Kerens Pumphrey got the nickname long before the cartoon sailor came along, thanks to his exaggerated expressions of surprise. Between the time Faulkner visited Gayoso Street in 1921 and published Sanctuary in 1931, “Popeye” Pumphrey enlivened the pages of evening newspapers with his alleged criminal exploits and miraculous immunity to prosecution.

In fact, those years saw Popeye evolve from small-time local hoodlum to front-page gangster. Police pulled Popeye, at the age of eighteen, for vagrancy in January 1921. Within three years, Popeye suffered thirty-three arrests. On a weapons charge in 1923, he drew a sentence of eleven to twenty-nine years, only to have governor Austin Peay intercede and parole him. Detectives also implicated Popeye in a safe-cracking incident and found him in New Orleans in 1926, dressed to the height of fashion, his tie displaying a diamond stickpin.

He beat the safe-cracking rap in time to face Prohibition-violation charges in November 1927. Things looked pretty grim for Popeye before Judge Harsh in Memphis criminal court. Harsh “was about to pronounce a heavy sentence on the boy whose drunken auto rides, fist fights and other exploits have made him a police character,” an Evening Appeal reporter observed. Popeye’s father pleaded for another chance. “He can’t be all bad, judge, for he has a mother and sister who have prayed for him,” said the elder Pumphrey. He then read a poem about a father’s love for his son, moving many spectators to tears. Harsh cleared his throat and said, “All right. I know he’s bad, but I’ll give him another chance….”

Popeye’s crowning gangster achievement happened June 23, 1929, outside the LaSalle Hotel in Kansas City, Missouri. Five men exchanged gunfire. Two died, including a Chicago tough named Ben Barretti. Popeye sustained only “escape” wounds to his backside, possibly while fleeing.

Popeye’s crowning gangster achievement happened June 23, 1929, outside the LaSalle Hotel in Kansas City, Missouri. Five men exchanged gunfire. Two died, including a Chicago tough named Ben Barretti. Popeye sustained only “escape” wounds to his backside, possibly while fleeing.

Biographer Blotner later excavated rumors of the rumors Faulkner heard—that Popeye Pumphrey didn’t let impotence get in the way of his sex life. This bit of gossip, it seems, inspired the scandalous outrage at the center of Sanctuary—the corncob incident.

Faulkner completed the manuscript in May of 1929. In October, The Sound and the Fury came out. Though revered later, nobody bought it at first.

Here’s where Memphis played a crucial role in the bard of Yoknapatawpha’s career. Forget for a minute that he’s Faulkner. Think of him instead as a novelist in his early thirties, a few sparsely printed books to his name, working the night shift at a coal-fueled power plant or sponging off his dad. He’s got to be desperate.

Faced with disappointing sales, an uncertain future, and another experimental manuscript in the works, already in galley form, Faulkner made his most blatant foray into literary commerce. In summer 1930—that date according to scholar Noel Polk—he drastically restructured Sanctuary. As the author, he bore the financial cost of resetting the galleys, but he clearly felt radical and substantial changes would pay off. By my comparison of the Sanctuary manuscript and the published work, Faulkner altered its idiosyncratic format into a more traditional narrative, and spiced it with what he’d later describe as “a cheap idea…deliberately conceived to make money.”

While the manuscript opens out of sequence, in the middle of the story after the corncrib murder, the novel starts at the beginning. As a cheap idea deliberately conceived to make money, traditional narrative structure makes sense. More unusual, in the line of his cheap idea, Faulkner also amplified Memphis’s prominence from Sanctuary manuscript to novel.

In an early scene set in a backwoods Mississippi bootlegging hideout, the author switched the word “thugs” to “folks,” changing “Why can’t those Memphis thugs stay there and let you all make your liquor in peace?” to “Why cant [sic] those Memphis folks stay in Memphis and let you all make your liquor in peace?”

It renders Memphis that much more sinister, making thug bootleggers typical folks by Memphis standards.

The answer to the question, by the way: “That’s where the money is.”

“I’ll take you back to Memphis,” Popeye tells the bootlegger Goodwin’s wife, in the next scene, lines that didn’t appear in the manuscript. “You can go to hustling again. You’re getting fat here laying off in the country. I won’t tell them on Manuel Street.”

There’s no Manuel Street in the real underworld, but the main drag in Memphis’s hustling part of town was named Gayoso Street for an eighteenth-century Spanish regional governor at New Orleans—Manuel Gayoso.

It is through Popeye’s actions that the human costs of Memphis corruption are levied in Sanctuary. The most recognizable feature of Popeye Pumphrey in Faulkner’s Popeye is his mysterious power. Popeye Pumphrey could not possibly dodge conviction on thirty-three arrests, or receive a gubernatorial pardon, without protection. Faulkner’s Popeye has a similar, hidden source of power. When the bootlegger Goodwin sits in a jail cell awaiting to be tried for a murder Popeye committed, he tells his attorney why he won’t incriminate Popeye: “Just let it get to Memphis that I said he was anywhere around there, what chance do you think I’d have to get back to this cell after I testified?”

Faulkner’s Popeye commits another murder and, even more awfully, defiles the feminine virtue of Mississippi debutante Temple Drake. The concluding scenes of Sanctuary offer opportunity for justice to be served, as Goodwin stands trial in Yoknapatawpha for the murder Popeye committed. Instead, a Memphis attorney materializes. He speaks not a word, but produces a surprise witness, who commits perjury in offering false testimony. Goodwin, a Mississippi man innocent of murder, burns.

Faulkner shipped off his revised galleys, and a few months later, in October 1930, As I Lay Dying came out. Like The Sound and the Fury, its acceptance as a classic would have to wait.

Faulkner’s Memphis foray may have saved his career. Published February 9, 1931, Sanctuary outsold As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury in its first month. It was his first bestseller.

It seems unlikely that Popeye Pumphrey knew about his literary immortality. Perhaps to the contrary of those impotence rumors, Popeye had contracted syphilis. During the months following Sanctuary’s publication, the disease withered his body and attacked his mind. He was only twenty-eight. In an apartment in Hot Springs, Arkansas, Popeye ended it with a pistol shot to his head on October 28, 1931. The Commercial Appeal noted, “The record of Memphis ‘No. 1 public enemy’ has been closed.”

Sanctuary holds a special place in Faulkner’s career. Its history takes him out of his tweed jacket and drops him, shaggy-haired and threadbare, into a brothel parlor. There, no one asks him about the struggle of modern man to define himself, or conflicts of the human heart. There, a plump and plumed madam insults his short stature and questions his manhood.

The book will always deserve its rating as Faulkner’s raunchiest. No one could seriously say that the book isn’t trashy and salacious. The criticism fits, in so far as the reader enjoys or disdains such themes. The extent to which the trashy and salacious are historically and culturally valid, established, long-practiced, and even celebrated and defining aspects of one of the great American cultural hotbeds remain underappreciated. Sanctuary is not the stream of consciousness, nonlinear, modern masterpiece that has come to define quintessential Faulkner. (Feeding the air of pretension some see in his followers and scaring off some would-be readers.) It nevertheless is quintessential Faulkner. Despite himself, he couldn’t pull off even a “cheap idea” without expertly surveying complex moral terrain, digesting a violently complicated and scandalous historical background, and animating characters with these forces they struggle to comprehend. It’s a pretty long way from Yoknapatawpha.