“Our country is a divided crime scene.”

—Donald J. Trump, Twitter, July 17, 2016

The Department of Homeland Security designated the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland a “national special security event.” As such, the city received funds to purchase 2,000 full sets of riot gear; 2,000 twenty-six-inch retractable steel batons; 2,500 steel barriers stretching nearly four miles; 10,000 sets of plastic handcuffs; twenty-four sets of body armor, including bulletproof helmets; a BearCat armored personnel carrier; two night-vision scopes; and an unspecified amount of tear gas.

The Cleveland Police Department has been under consent decree since a 2014 investigation by the US Department of Justice found that its officers engaged in “unreasonable and unnecessary use of force”—shootings, head strikes with impact weapons, tasers, chemical spray, fists—sometimes during welfare checks, sometimes against people who were mentally ill or in crisis. The investigation followed the gunning down of Tamir Rice (black, unarmed), age twelve, in a playground, by two (white) officers. According to the last census, Cleveland is approximately 53 percent black, 37 percent white, and 10 percent Hispanic/Latino. More than half of Cleveland’s children—54 percent—live in poverty, as do approximately two in five adults.

For seven days in July, on the occasion of the Republican National Convention, photographer Ryan Spencer Reed and I went to Cleveland to report on the city in image and verse.

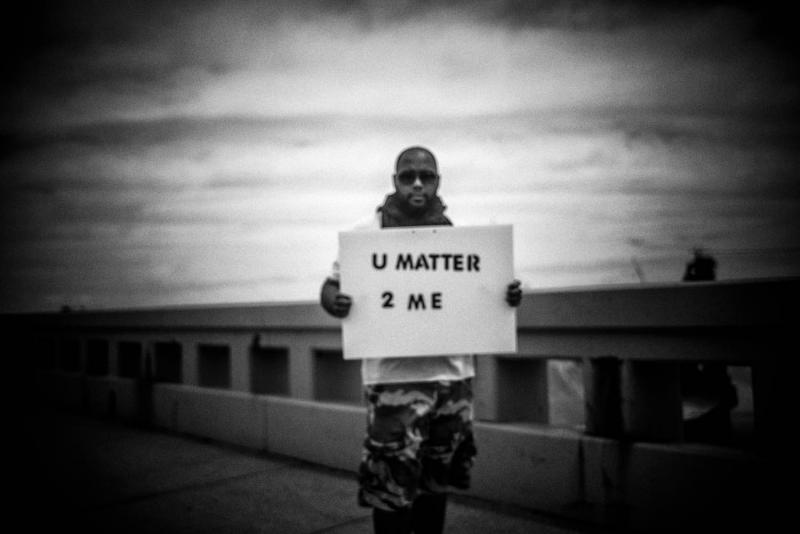

On the Sunday before the RNC began, we headed to Circle the City with Love, a silent protest led by nuns, where thousands of people joined hands in the baking midday sun on Hope Memorial Bridge. Sister Rita Petruziello gave instructions: We would stand in silence for thirty minutes “putting the power of love into the energy fields,” she said. “Science tells us that energy has memory, and the collective memory of thousands of us has a very powerful and lasting effect on the universe. Spirit is energy. Energy is love. Love is God.”

Hope Memorial Bridge was renamed after the father of comedian Bob Hope—a local stonemason who helped build the Guardians of Traffic, pairs of massive statues that stand on pylons at each end of the bridge and are meant to symbolize progress in transportation. The Guardians towered impassively over us as we listened to the rush of wind, to black military-style helicopters whirring across the sky, the cry of a lone ring-billed gull, cars crossing the highway over the Cuyahoga River, and a chorus of sirens in the distance. A prop plane pulled a banner overhead that read protect real marriage. A blissed-out woman in a white turban, her eyes closed, breathed steadily. At the end of the protest, people stood in line to hug rows of bicycle cops.

Bob Hope specialized in zingy one-liners (“I thought about running for the presidency, but my wife said she wouldn’t want to move into a smaller house”). He grew up in Cleveland, and tells a story in his autobiography about himself and his pal Whitey Jennings being worked over by a gang of seven knife-wielding thugs in Rockefeller Park. Hope and Jennings walked themselves to Mt. Sinai Hospital, where Hope needed fourteen stitches to close a wound that ran from his back to upper arm—“a real beaut.”

Throughout the convention, we passed phalanxes of police on foot, horseback, bicycle, and motorcycle, calling out uniform patches and insignias from Florida, Kansas, Kentucky, California, Oregon, Texas, Indiana as we went. Near the Quicken Loans Arena, on the sidewalk leading up to East Fourth Street, vendors—most of them African American—hawked bobbleheads, T-shirts, caps, bottles of water, buttons: veterans for trump; make america great again; welcome to the republican national convention; rnc cle; keep calm vote trump; bomb the hell out of isis; blue lives matter; there’s no stopping this train—trump 2016; let’s get america’s engine started again. Nearly all of the convention attendees were white. According to the Washington Post, only eighteen of the 2,472 RNC delegates were black.

Hanging on a wall in the main branch of the Cleveland Public Library was the front page of a 1924 edition of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, which was almost exclusively dedicated to the eighteenth Republican National Convention, the last one held in the city: “Ku Klux Klan activities occupied the center of the stage yesterday in the Republican convention preliminaries. After the arrival in Cleveland of Dr. Hiram W. Evans, Imperial Wizard…and about sixty other Klansmen from all parts of the United States, a meeting was held, after which it was reported: That the Klan is for the election of Senator James E. Watson of Indiana as vice president of the United States.” The 1924 convention was the first to give women equal representation.

More buttons for sale near East Fourth: girls just wanna have guns; hot chicks for donald trump vote 2016; hillary for prison; hillary’s lies matter; kfc hillary special 2 fat thighs 2 small breasts…left wing; vote no to monica’s ex-boyfriend’s wife; life’s a bitch—don’t vote for one.

Outside a convention function at Tower City Center, Superman stood dressed in a slightly baggy royal-blue nylon uniform: red boots, blue tights, red shorts, a yellow-and-red S sewn on his chest. A portrait photographer was shooting him in front of a backdrop of a giant bald eagle airbrushed onto an even more massive American flag. Next to him, two women posed with their arms outstretched, palms flat (it looked like a doubling down on a Nazi salute) until he corrected them, had them make fists instead, and there they were flanking him, each with one fist held in the air—maybe power, maybe victory.

Superman was created during the Great Depression by two Jewish high-school students in Cleveland, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster. The 1932 prototype was of a villainous superhero, and later he became the hero we know as the Man of Steel. You can still visit an Ohio Historical Marker on East105th and St. Clair commemorating this.

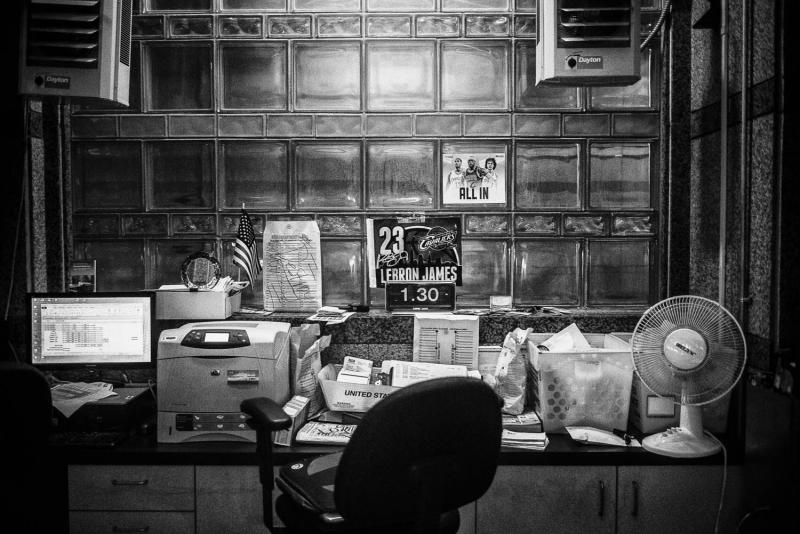

People from Cleveland generally believe the city is cursed—in weather and economics, but especially in sports. The city failed to win a championship in any major-league sport from 1964 to 2016. That’s a combined 156 seasons of straight disappointment, among the Browns, the Indians, and the Cavaliers. Bob Hope bought a small stake in the Cleveland Indians baseball team in 1946. In 1948, the Indians won the World Series, but then had a thirty-five-year slump that lasted from 1960 to 1995—when they made it to the World Series, but lost. FirstEnergy Stadium, where the Browns play, is also known as the Factory of Sadness. Clevelanders are unendingly loyal to their sports teams despite constant failure; they take great pride in this.

Reed and I wandered through the West Side, the East Side, and inner-ring suburbs on foot, by car, by bus, and Rapid. We spoke with Clevelanders all over the city—barbers and transit workers, hospitality-industry workers and waitstaff, doctors and teachers, and people we met in the streets and at events—including vendors and convention delegates, RNC attendees and protesters. There were tense moments, and moments of weird synchronicity (at Tower City Center, Reed ended up standing at a urinal next to John Kasich). We went through neighborhoods with slumping duplexes, brick houses with windows blown out and doors boarded up, and empty lots where houses once stood. We passed corner stores, barbershops, and storefront child-care centers: Apples of Gold, Apples of God, Circle Tyme, Bright Star Kiddie Tots, Ever Changing Educational Center, Nana Ella’s Gentle Loving Care, Brightside Academy.

In getting to know Cleveland during the RNC, I often felt as though I was looking through a window—sometimes at things that passed by so quickly they were just composites; sometimes at a scene inside I could view but couldn’t parse; sometimes at a moment I tried to narrate; and sometimes at my own reflection, which could obscure what diorama, tableau, event, tragedy, celebration, or bit of life was going down inside.

Washington Post reporter Dan Zak wrote: “We were promised a riot. In Cleveland, we got a block party instead.” And I think of something Rapid Transit Authority supervisor Hilda Perez said to us: “I live on the near West Side. I live in the ghetto, as they call it, or the ’hood. Those are the phrases they use for these areas. But I live in the ’hood, and it doesn’t bother me. I don’t care if you’re purple, green, or white. I’ll go, ‘Hey, how you doing? I’m having a party. You’re welcome to come if you wanna come. If the noise gets too much, just knock on the door and let me know.’ ”

Make America Safe Again

Joyce Sellers, RNC attendee from Dallas

The silver-haired woman is hard to miss, in her

coordinated all-American true-blue skirt suit,

matched star-spangled earrings, red-and-white

striped purse. She’s kindly, trying to find stores

to buy T-shirts and souvenirs, stops us to chat.

Well, I just arrived yesterday, she says, and I went

to the Trump last night. He won on the first ballot,

which thrilled me. I’ve been for him from day one,

and I’ve convinced nearly all my friends in Dallas

to vote for him. I just think he’s the answer to our

problems today, and we have a lot of problems in

this country. As I see it, people are afraid now.

They have fear. They have anxiety. And I think

he’ll bring back happier times—a calm and assured

feeling for our country and our people. So I’m just

very much for him. A lot of things he’s for—all of it—

makes a lot of sense. I didn’t know the man. I never

watched his TV program but maybe once or twice.

You’re fired. I’d heard the name. In fact, I couldn’t

even remember his name hardly before I heard him.

But when he made his first speech I thought,He speaks

for me. And I think that’s why he won. Because so many

other people felt the same way. I pray about it a lot.

That’s what I do. God is in control, so I trust in him

to help me out and he does. Meeting y’all is no accident.

It’s all according to his plan. So here I am. I thought

it was too long a journey for someone my age, but I’m

always sure everything is going to work out. And it does.

Make America One Again

Bus 3: Superior

They let most everyone work from home. But I had to come in.

—woman in front of me in business casual

(the bus dings, decelerates, sighs its doors open, and her voice

is swallowed as the bus groans forward again—a leap from work

to children)

…she just turned six yesterday, and she want to keep everything—

every single thing. Like a little tag. I tell her to throw it away.

My last child—he is seventeen.

—woman across from her with vitiligo

We pass Bohn Towers & Promise Academy on Superior

We pass the Convention Sideshow—an Uncle Sam with mouth as door

(Be Marveled / Amazed)

There are blue fingers pointing the way in

The bus speaks: Next stop Superior & East 30th Street

We pass Auto-Diesel Piston Ring Co.

Juniors Buy Wise / Ohio Lottery

Defend the Land posters pasted to brick

There’s a boy on the bus with his father, who looks older—in his fifties.

The boy is maybe six. I saw them downtown walking from the protests

at Perk Plaza, where lines of cops stood to protect Ohio Savings Bank

and its storefront row of windows with their arms crossed at the wrists,

gas masks strapped in black pouches to their thighs.

The boy and his father sit perpendicular to each other on the bus.

The boy fidgets. He reminds me of my son, kinetic, always in motion.

Daddy we close to our house

I could tell by that thing—that top of the building

Oooh McDonald’s

(His Ninja Turtle cap is too big for his head)

Just down the block to go

(He holds his water bottle in his shirt and every so often it rolls out)

I won’t be dropping it

(he promises—it thunks—we all look at our feet, nudge it back his way)

The bus isn’t air-conditioned and it’s nearly ninety degrees inside and out

in the late afternoon heat / in the hard early evening light

The bus speaks: Next stop Superior & East 66th Street

We pass Lottery WIC ATM Pay All Your Utility Bills Fried Chicken Beer

& Wine Gyros Money Orders Soft Serve Check Cashing We Buy Gold $$$

We pass more Defend the Land posters

The boy and his father are still on the bus.

We pass Kiss Beauty Supply blinking red & OPEN

The bus speaks: Next stop Superior & East 82nd Street

We pass Moe’s Junk Cars Auto Tires Service Repair

The boy’s feet dangle above the bus floor.

His father wears a green T-shirt: Hands Up / Don’t Shoot.

The boy rises on his knees on the seat to pull the cord

and they get off at East 85th and Superior.

We pass more We Buy Gold $$$ signs

We pass Malik’s Beauty Supplies Plus Discount—

where we will match any competitor’s price if you bring in their ad!

We get off at the Superior Rapid Station.

Three guys sit on a ledge next to a pit bull lying

on the ground panting in a puddle of pee. I can count

its ribs. Want it? they ask. I don’t answer.

I climb the out-of-service stairs of the escalator.

Don’t be too happy / You’ll get soft

—RTA station graffiti

Make America Work Again

Allstate Hairstyling & Barber College (est. 1961)

Drawn by the red-and-white flag-striped awning,

we stop and look in the window, where, though

it’s Sunday, a man in scrubs and black high-tops

pushes his blue mop head between each maroon

hydraulic chair turned to face its neighbor across

the aisle, goes at the linoleum until it shines like

a police helmet’s dome reflecting noon-day sun.

Every barber’s chair holds an emptied white plastic

trash can on its silver footrest, and 100 pragmatic

dreams cut from $7 Afro Shape-Ups and $8 Fades.

When we return, the place is filled with apprentices

in black student barber jackets leaning on their stations

shooting the shit or nodding to music, constant murmur

over the buzz of a few electric clippers—you gots to—

yeah yeah yeah—hey y’all done with these combs?

A lot of folks left town just to get out of the way,

says a student—a former marine still wearing dog tags.

One reason they picked Cleveland is if you don’t win

Ohio, you lose. When you lose Ohio, you can’t win

the race. The owner chimes in. The RNC is killing us.

I didn’t realize how bad it was going to be. He means

all the roads are closed so no one is headed past here.

He means there are hardly any customers. Nobody

is really happy about this convention business.

I ask Mike about placement rates for his students.

He holds up a stack of paper phone slips—messages

from people all over the country looking for barbers—

and flips through them. Here’s one from East Side.

Vermillion. Had one in here from Gainsville, too.

A maroon-jacketed instructor, before we leave, says,

You have to take a picture of this, and pulls out a man’s

plastic head labeled with a carefully markered mosaic

of fake beard made from numbered arrows, drawn

to teach students the proper way to shave customers.

He sets it on a divider between the register and an empty

bench where clients wait for the next available chair.

It looks at us, with its mask of sadness. More blank

heads rest on top of the Coke machine, beside a sign:

If you are Grouchy, Irritable, or Just Plain Mean,

there will be a $50 Charge for Putting Up With You.

We spot the same sign at Thinline Barber Shop on

St. Clair, where the two barbers, Darcel and Ray,

went to Allstate in the ’70s, came up with the owner

of the school’s father, call him by his last name—

D’Amico—say he was real cool, a good dude.

As he’s talking, Darcel holds a rectangular mirror

in his left hand, wields clippers in his right, says,

The thing is, you gotta love what you’re doing.

If you don’t love it—this is what we love to do.

He trims the back of his own head as a framed print

of Martin Luther King Jr. mid-oration looks on.

The night before, at the RNC, Mike Pence said,

“It will be our party that opens the doors for every American

to succeed and prosper in this land,” but Thinline

is in South Collinwood, a neighborhood the delegates

will never see. More than half of Cleveland’s children

live in poverty—second only to Detroit. The night

we arrived in the city, seven people were shot. We

more of a family in here, says Ray. Because, you know,

everybody—you hear the music, right? It’s calm,

it’s cool. The shop stereo croons smooth R & B—

Earth, Wind & Fire, Mary J. Blige. You come in here,

you feel at home. We get a lot of guys come in

and say this is the only place I can go to sleep,

or relax. And there’s Take 6 singing, never mind

your fears—brighter days will soon be here…

Make America First Again

Too strong

is what the announcer dubs Steph Curry’s

flubbed shot that bounces diagonally

off the backboard. This is game seven

of the NBA finals, and Cleveland goes on

to defeat the Golden State Warriors,

but we don’t know this yet, because

we’re still watching the game, jammed

into an alcove where it’s live-streaming

from someone’s laptop onto a wall,

since the one sports bar in town closes

at ten, and we’re using Tommy’s mom’s

password for her Time Warner account

though Tommy is out of town on what

everyone jokingly refers to as a “conjugal

visit” with his girlfriend. Dominica starts

telling us about a bar in San Francisco

where you can only order a drink using

three adjectives—no names—and then

Nate says, “someone should write a poem

called Too Strong,” and Stephen doesn’t

volunteer, though he’s won a Pulitzer

and is sitting behind me also rooting for

the Cavs, saying things like my goodness

and he’s the best closer for his size.

“You have to give the context in your

poem,” mansplains Nate, who goes on

to point out that “too strong” is a hyper-

masculine way of saying Curry basically

just fucked-up the shot. It’s important to

point out here that Cleveland hasn’t won

a championship in any sport since 1964—

that’s a fifty-two-year curse if you’re anti-math.

I am well versed in thesadness of Cleveland—

skies hanging likelead most of the year,

husks of buildings, smokestacks pumping

raw flame over downtown. My husband

grew up in the sadness of Cleveland,

and we return there every Christmas to more

unemployment, more foreclosure, more

poverty, more shitty weather. When LeBron

left Northeast Ohio, my husband actually

burned his replica jersey in the yard, wouldn’t

mention his name for three long years of anger

and mourning. He uses Cleveland sports to

teach our sons about failure and perseverance,

with a heavy emphasis on the failure. But

here’s LeBron on-screen, lugging his city’s

championship dreams like a bag of rocks.

Forget Tamir Rice, age twelve, gunned down

by police for being black, for playing with

a toy gun in a park, left to bleed out on a

sidewalk. Forget that Cleveland is the

poorest city in America other than Detroit.

LeBron’s stuffed this game with thunderous

dunks, fadeaway jumpers, and blocked shots,

towing his teammates along in his ferocious

wake. And when LeBron goes down in the final

minute of the game, writhes on the court

in pain after landing on his wrist, we all

want him to get up—even the folks rooting

for Golden State. Get up, LeBron! Nothing

comes easy to Cleveland. The next morning’s

paper sports a photo of LeBron embracing

power forward Kevin Love, next to headlines

about Venezuelan food riots, triple-digit

temperatures in the West, vigils for

victims of the Orlando massacre, and

the Colorado woman who fought off

a mountain lion attacking her five-year-old

son—literally reached into the animal’s

mouth and wrested his head from its jaws.

Too strong. In the belly of fear and rust

and shame there is no such thing.

To pry open something with your bare

hands, look into the gaping maw

of the beast that eats your sons—

the lion, the bullets, the streets, racist

cops, heroin, despair, whatever is most

predatory, and say enough—we will triumph,

motherfuckers. At the game’s end, LeBron

and the Cavs’ coach Tyronn Lue sobbed

without shame. “I’ve always been tough

and never cried,” Lue said. And LeBron

at the postgame mic, wearing a cut-down

net like a necklace, says, “I came back to bring

a championship to our city. To a place

we’ve never been. We’ve got to get back

to Cleveland. We’re going home.”