1.

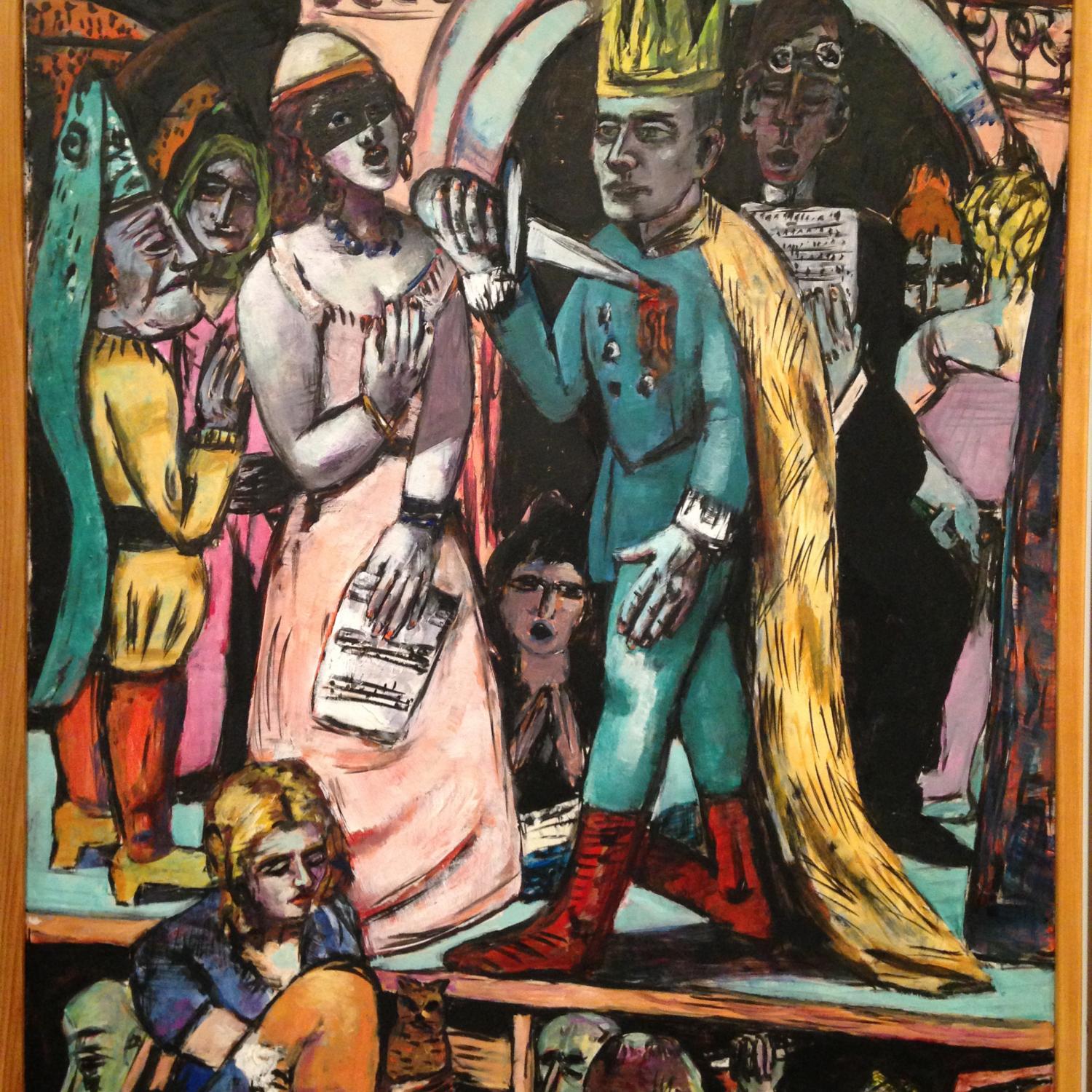

“Actors” was painted by Max Beckmann in 1941 and 1942 when he was a refugee from Nazi Germany in Amsterdam. It is the painting I photographed most in the years we were living in Cambridge. I tried repeatedly to write about it, but didn’t succeed. We were mostly living pretty quietly, with our little children, but certain days were torn apart. There was the Boston massacre, and the lockdown. That evening in our kitchen we could hear the shots of the capture in Watertown. Others, the Charleston massacre, and the Orlando one; I know I went to look at the Beckmann after the Paris attacks at the Bataclan. On those days, I wrote notes to the people I knew who might have been nearby. The Beckmann seemed to reflect something about our circumstances, but it was hard to name the relation. Violence is close by. There is the dagger that the man playing the king, who is a self-portrait of Beckmann, is piercing himself with. There is another dagger in the panel on the left, almost in the ear of the man crouching and desperately reading foreign news, the New York Times. People are all crowded together and yet each figure seems remote, as if a kind touch between them would be unthinkable. Over time, I did learn that all the figures are necessary. If you hold up a hand to cover those who crouch on the stairs, the feet and faces below stage, there are many fewer dimensions, but this simplification turns out not to clarify the painting. The interpenetration suggests many meanings—about injury, proximity, theater, war, about what it is to witness and what to watch from an insuperable distance. On the days when violence erupted this seemed the only thing to think about, but then on other days, it was submerged.

2.

You might consider Beckmann’s “Actors” as a meditation on the phrase “theater of war.” The words acquired their modern usage in Carl von Clausewitz’s On War, a powerful text in military history, unfinished when he died in 1831. The phrase is based on his experiences in the Prussian Army during the Napoleonic Wars. Clausewitz writes that a theater of war is “…such a portion of the space over which war prevails as has its boundaries protected, and thus possesses a kind of independence…. Such a portion is not a mere piece of the whole, but a small whole complete in itself.” A small whole complete in itself, separated, and only indirectly influenced, by the rest of the war. In the painting, Beckmann depicts his fellow émigrés, exiles of Nazi Germany, as actors, but they might be rehearsing, or getting ready for a performance; they stand around and watch one another. The boundaries do not seem clear. There is the shocked, masked woman who witnesses the stabbing, and holds a hand to her pale pink dress; she seems to be in the play in a way that the figures behind her aren’t. In the panel to our left, the very large face seems to look out at us, but the girl with the cat is in a reflection unaware of our presence. This is not a theater that is easily separated out from life. Beckmann seems to be saying that we do not have those independent theaters that Clausewitz defined, that we are all somehow actors in the spectacle of war. But to me, on the days when I read of violence that feels proximate and potential, it feels impossible to really act. Maybe this is because there are so many insurgent and unexpected theaters of war—where a marathon or a school, a church or a club suddenly is such a theater. These acts and actors don’t seem independent, or complete unto themselves. Beckmann’s painting, too, has witnesses in ever-larger concentric circles. Perhaps without a clear theater of war it is harder to understand or undertake action.

3.

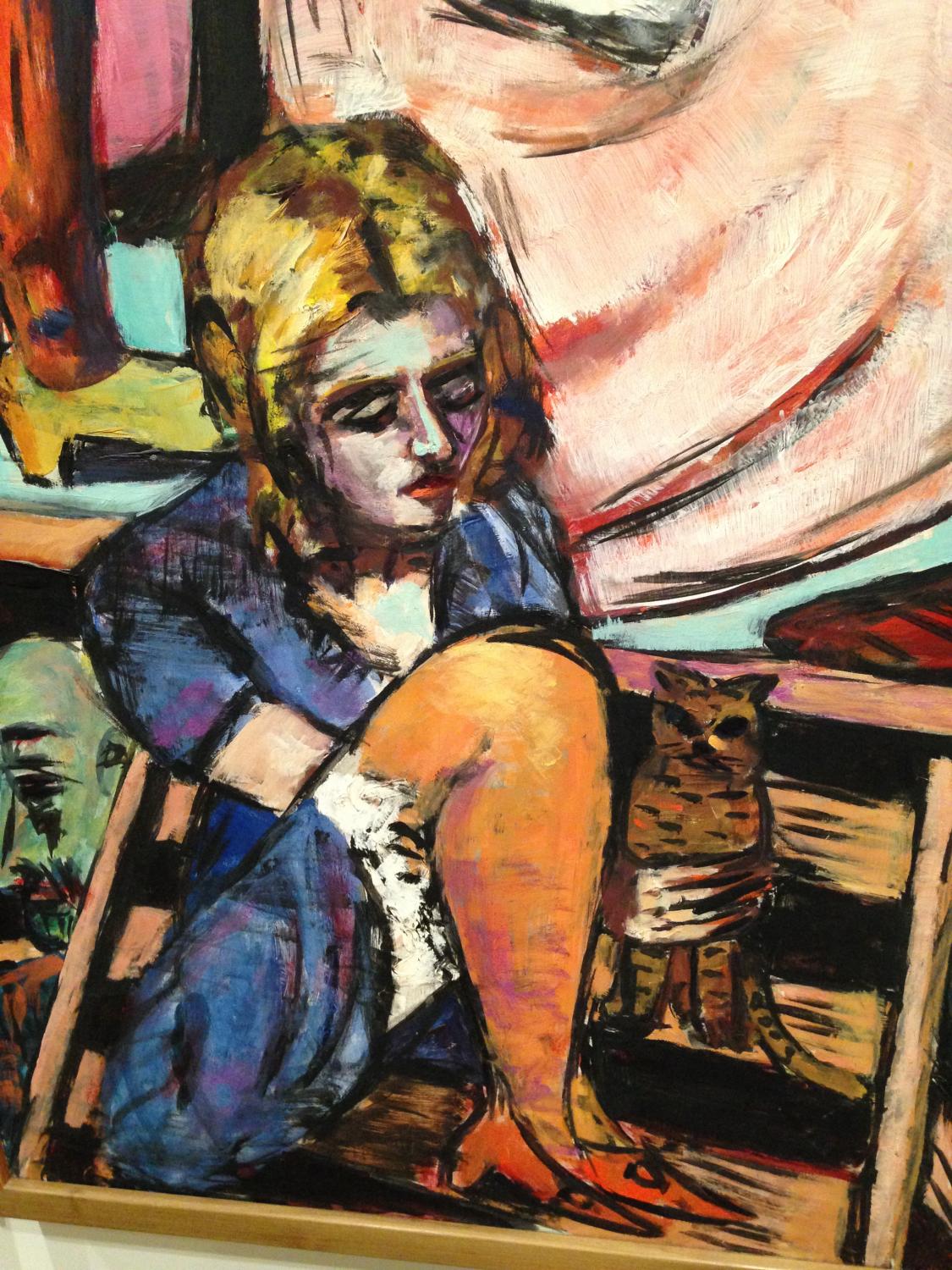

When I look back at my pictures of Beckmann’s “Actors,” I see that I have very often paused over the girl with the cat. She sits quietly. I think she seems comforted by touching the cat. She is almost an oasis amid the gesticulating and spying actors in the painting, although there is no way to photograph her without the looming green face behind, the sweep of the pink dress of the disturbed woman above. It may be that she is more than quiet, she is mute. But it is possible that she is in some kind of communion with the cat, and in some way represents the memory of touch without menace. It is hard to read her face. Everything in the painting is cryptic, and Beckmann, working in exile in Amsterdam during the war, must not have felt at liberty to be open. Some part of the painter is obviously above the boards, in the self-portrait he made of himself stabbing himself, but something of his silence, his brooding, the thoughts of the past and the future that are painful to allow himself to have, sits below on the steps, a careful hand around a cat.

4.

In Beckmann’s “Actors,” the figure stabbing himself at the center of the central panel is a self-portrait of the painter at a younger age. Max and Mathilde Beckmann had been living in exile in Amsterdam since 1937; they left Germany the day after the Nazis opened the notorious exhibition of Degenerate Art in Munich. In 1938, a show was mounted in London that Beckmann agreed to exhibit in—the show took a complicatedly quiet view of the maneuvers of the German government. At the time of the exhibition, Beckmann gave a speech, one of very few public statements he made about his painting. It, too, is complicatedly quiet—reading it I feel that certain words would have had for his hearers subtleties that pass entirely outside the audible range for me. “Human sympathy and understanding must be reinstated. There are many ways and means to achieve this. Light serves me to a considerable extent on one hand to divide the surface of the canvas, on the other to penetrate the object deeply.” This means something about perception, about perceiving other people in an extent of space and duration of time that allow them their humanity. The Beckmann triptych is trying to see people with human sympathy and understanding, but in an atmosphere of total war even the use of light to make divisions and penetrations may start to feel like a kind of violence. In the face of the painter who plays the injured king of this small domain, you can see something of how it feels to live estranged in a small theater of war among myriad theaters of war, each figure bounded, and, though impinging on one another, not able to save or hold the others. Beckmann wrote in his speech: “Often, very often, I am alone. My studio in Amsterdam, an enormous old tobacco storeroom, is again filled in my imagination with figures from the old days and from the new, like an ocean moved by storm and sun and always present in my thoughts.”

5.

After we moved to Chicago, I saw a Max Beckmann drawing at the Art Institute called “Birdplay.” It was made in 1949, four years after the end of the war, two years after the Beckmanns arrived in the United States. When I saw it, I was very moved by the intensity with which the women are listening, the levitating relief with which the birds are telling what happened. It seemed to contain some clues about the Beckmann painting I had never managed to write about, the one in Cambridge, “Actors,” 1941-1942, that I had photographed for years. In looking at that vast triptych, and trying to understand how the theater and actors Beckmann portrayed stood in relation to the war that surrounded them, I had struggled, without knowing it, with the fact that, in the theater of total war, it may feel, or even become true, that there is no real audience, which is to say, there might be nothing outside the theater. Even I, the spectator of the painting, had not found a way to be an audience member, I was another failed actor. There was no story to be gotten across to me or by me; it was not clear in what direction human sympathy might lie. But in Birdplay there is a story, and people listening. It is still possible to be beyond the theater of war. Things have gotten worse since we lived in Cambridge and I could not write about Actors. Nevertheless, I did, by chance, come across a picture that suggested something about what happened to the refugee Beckmanns after they thought they might never get out of the endless play. They did find a place to alight where they could tell and be heard, could hear themselves. I believe, from my photographs, that Beckmann was morally careful, and that he had not left this possibility out of the wartime painting. Perhaps that is why I so often went to see it, though I am not sure I ever learned to stand in relation to it, and to hear what its witnesses were trying to say.

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.