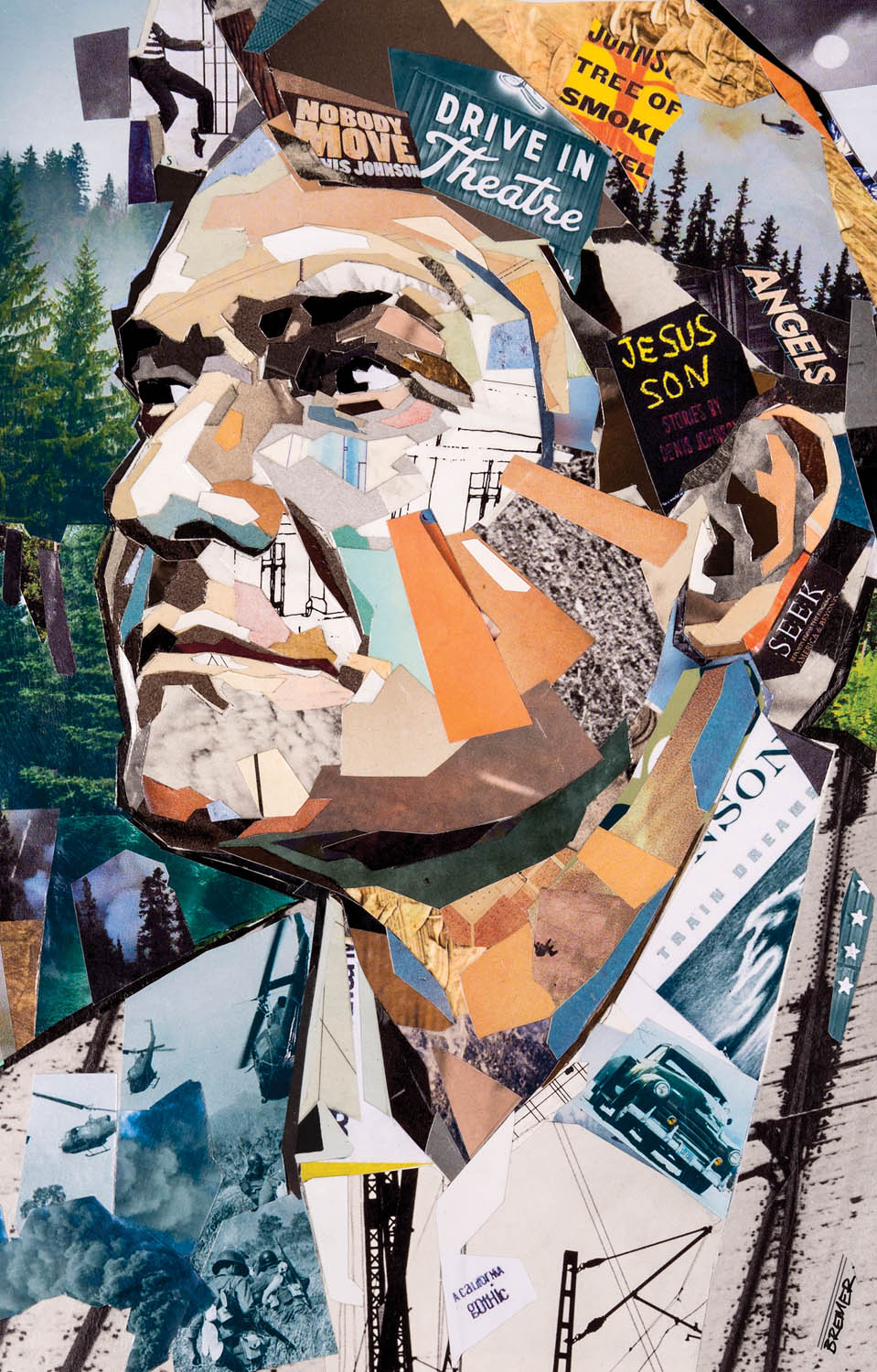

I resisted, at first, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. This collection of five short stories, the final new book by Denis Johnson, was announced shortly after the author’s death in May 2017, at sixty-seven, and although a galley arrived late that summer, I held it in abeyance for as long as I could. Something—the idea, perhaps, that these were the final new sentences Johnson would ever publish—made it feel like a last will and testament. “It doesn’t matter,” Johnson writes in “Triumph Over the Grave,” one of the stories gathered here. “The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.” The line recalls “Late Fragment,” the closing poem in Raymond Carver’s A New Path to the Waterfall, six brief lines of self-interrogation inscribed during his last days of life. “And did you get what / you wanted from this life, even so? / I did. / And what did you want? / To call myself beloved, to feel myself / beloved on the earth.” Johnson, however, provokes a different resonance, a different sort of immediacy. If Carver is looking back, creating his own epitaph, Johnson is projecting forward, speaking to us in a present he no longer occupies. I’m not dead, he insists. But maybe. The conditionality, the sense of language, of narrative, as instrument of both redemption and the impossibility of redemption—these have been among Johnson’s most abiding themes all along. “We lived in a tiny, dirty apartment,” he writes in “Out on Bail,” one of eleven linked stories that comprise his 1992 masterpiece Jesus’ Son. “When I realized how long I’d been out and how close I’d come to leaving it forever, our little home seemed to glitter like cheap jewelry. I was overjoyed not to be dead.”

I’m interested in the literature of death—not the literature of the survivors, but that written by the dying—although this is not exactly what The Largesse of the Sea Maiden represents. Indeed, it’s more accurate to frame it as an example of the book as last thing, inspired less by the impending demise of its creator (as is A New Path to the Waterfall or, say, Jenny Diski’s In Gratitude) than by the more general condition of mortality the writer and the reader share. Literature complicates this dynamic in a couple of essential ways, beginning with its ability to break down, for a moment anyway, the distances between us, our inevitable and unyielding loneliness. Then, of course, there is the matter of time. I’m not dead yet, Johnson tells us correctly. But his codicil, that maybe he will be by the time we read him, is also correct. Here we see the true transference that literature offers, a conundrum in which our thoughts, our beliefs, our expression, can survive us, even if we, as frail and temporary beings, do not prevail.

I think of Augustine, writing in the fourth century that “[l]ife is a misery, death an uncertainty.” The sentiment remains as relevant, as living, in this moment as it was in his. Where The Largesse of the Sea Maiden leaves us, then, is not with testament so much as with a sliver of the author’s living soul. I’m referring to pragmatics, not theology: If we animate the books we read, bringing them to life through our engagement, our intercession, then is it an act of preservation to hold off on reading when there will be no more? This was my experience with another Carver title, Cathedral, which I purposely held off reading for a few years after he died in 1988. I once felt about Carver the way I have come to feel about Johnson: that he was the most transformative and moving writer of my adulthood, the one whose books I would have most wished to have written, in addition to all else. Why? Again, it’s his sense of presence, but also the way Johnson balances wonder and degradation; transcendence and despair. “Down the hall came the wife,” he writes in “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” which opens Jesus’ Son and may be the most vivid short story that I know.

She was glorious, burning. She didn’t know yet that her husband was dead. We knew. That’s what gave her such power over us. The doctor took her into a room with a desk at the end of the hall, and from under the closed door a slab of brilliance radiated as if, by some stupendous process, diamonds were being incinerated in there. What a pair of lungs! She shrieked as I imagined an eagle would shriek. It felt wonderful to be alive to hear it! I’ve gone looking for that feeling everywhere.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden is a very different book than Jesus’ Son; even to compare the two seems beside the point. “When I write,” Johnson told me in an email correspondence occasioned by the publication of his 2014 novel, The Laughing Monsters, “I don’t think in terms of themes—or think in any terms, really. I’m making what T.S. Eliot called ‘quasi-musical decisions.’ I’m just improvising and adapting, and in that case I suspect the story’s course reflects the process of trying to make it.” Later, he described the process more metaphorically: “I get in a teacup and start paddling across the little pond and say, ‘In seven weeks, I’ll land on Mars.’ Five years later I’m still going in circles. When I reach the shore in spitting distance of where I started, it’s a colossal triumph.” What’s most remarkable about that revelation may be how recognizable it is; ask most writers and they’ll offer their own version of the same. “It’s like driving a car at night,” E. L. Doctorow said of his process in a 1986 Paris Review interview: “you never see further than your headlights but you can make the whole trip that way.” For Joan Didion, the mechanism is more internal; “I write,” she acknowledges in her essay “Why I Write” (the title is borrowed from George Orwell), “entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” What all of them (and Orwell, too) are addressing is what we might call the living line, the place where we encounter the author in the midst of exploration, on the very edge of what they can imagine or believe. Such a quality sits at the heart of Johnson’s project, and not only his fiction; among my favorites of his books—indeed one of the few I consider flawless—is Seek, a 2001 collection of essays and reportage. “I’m living in the Bible’s world right now,” he tells us, describing his experiences in Somalia, “the world of cripples and monsters and desperate hope in a mad God, world of exile and impotence and the waiting, the waiting, the waiting. A world of miracles and deliverance, too.” A world, in other words, where anything can happen, for good or ill. “I was lurking there in the dark, trembling, really, from the pit of my stomach out to my fingertips,” he writes in “Beverly Home,” which closes Jesus’ Son. “Two inches of crack at the curtain’s edge, that’s all I could have, all I could have, it seemed, in the whole world.” The living line again, writing not as an art of conclusion but one of asking questions, and narrative a device not so much designed to tell a story as to immerse us in a moment, a succession of moments, bubbles of breath less preserved than never quite exhaled.

The point is that, for Johnson, no story is ever really finished, or at least not quite resolved. Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t, which is part of the pleasure, and the challenge, of reading him. Of his twenty books, many come with difficulties: Already Dead, with its coterie of ghosts clustered along the cliffs and beaches of California’s North Coast; Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, which ping-pongs between grace and madness before unraveling entirely at the end. And yet, such failings are, in part, reflections of the characters’ incompleteness or lostness, the sense that they are about to (or already have) come unglued.

In the first of these novels, a drifter named Carl Van Ness, who is a “psychotic soul, referred to in most mythologies as a demon,” disrupts the narrative like an agent of chaos, convinced that his own failed attempts at suicide are successful and that karma is returning him, again and again, to his damaged life. This is not abstraction but belief, reality—the mystery, as it were, asserting itself. “Did you think we were just thinking?” Van Ness asks. “Thinking forbidden thoughts? Imagining heresies? Pretending to recognize moral systems as instruments of oppression and control?” Something similar is true of Leonard English, another unsuccessful suicide who, in the second of these novels, finds himself in a conflict of cosmic terms. “God is a universe and a wall,” English insists. “But there is a pattern, a web of coincidence. God…is the chief conspirator.” And this: “There are no coincidences to a faithful person, a person of faith, a knight of faith.” That’s great writing, not just the language but the meaning, the investigation, with its faith that literature is about the questions, not the answers, that all storytelling is conjectural. What does it matter if the novels fall apart or don’t quite hold up if the tightrope they are walking is so meaningful? It is the tightrope that matters, more so than whether, or how, we emerge on the other side. Johnson describes the process, or the movement, early on in “Triumph Over the Grave”: “It’s not much different, really, from filming a parade of clouds across the sky and calling it a movie—although it has to be admitted that the clouds can descend, take you up, carry you to all kinds of places, some of them terrible, and you don’t get back to where you came from for years and years.”

“Triumph Over the Grave” occupies the center of The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, and not only because it begins in the exact middle of the book. Rather, this is a narrative that—not unlike the collection as a whole—evokes Johnson as he is and as he was: author, teacher, moral being, lost soul adrift in an indifferent universe. Narrated by a novelist recalling his experiences at the University of Texas at Austin (where Johnson taught for a time, at the James A. Michener Center for Writers), it is, in every way that matters, a ghost story, although the ghosts don’t behave as we expect. Johnson makes this explicit from the first paragraph, which begins, “Right now, I’m eating bacon and eggs in a large restaurant in San Francisco”—a pedestrian opening, artless almost, but deft in the way it draws us in. Immediately, the narrator sees a woman in the restaurant who resembles the wife of an old friend. He calls the wife, only to discover that his friend has just dropped dead. “I have to call my sister,” she tells him, “all my family in San Francisco,” and then he watches as the woman in the restaurant “stops eating, sets down her fork, rummages in her purse—takes out her cellphone. She places it to her ear and says hello.” Johnson is describing serendipity in action, or more accurately the interplay of serendipity and purpose, albeit at a level underneath human (or conscious) intention, a kind of ley line of the soul. All things are connected, which is another Johnson fascination, if we know how, or where, to look. Here, the narrator’s experience in San Francisco yields to a series of reminiscences about dying friends, including a man whose deepest connection is to his ex-wife, suffering from dementia, and a writer visited by his dead brother and sister-in-law. “To be clear, I hadn’t seen any scorpions or any people or any ghosts,” the narrator reassures us (while perhaps reassuring himself). Either way, we are in the Bible’s world again, with its monsters and its miracles. The boundary is porous between the living and the dead. This is both metaphoric and entirely, brutally, actual; it is symbol and sign. We are in “a world without forward or backward, without logic, like the world of dreams,” Johnson tells us, and the trick is that he is not only referring to his characters but also to himself. I think of Schrödinger’s Cat, the famous thought experiment that seeks to explain quantum mechanics and the role of the observer in determining outcome; Johnson is up to something similar. All the deaths, all the ghosts and manifestations, the assertions of the dying—what do they mean, how are they heightened, when the teller, too, is dying, if not exactly in the context of the tale?

This is a tricky path to travel and it returns us to the idea of The Largesse of the Sea Maiden as last thing, a reminder of its author’s mortality, if not exactly (or entirely) an expression of such. Stories like “The Starlight on Idaho,” which first appeared in print in 2007, and the magnificent “Strangler Bob,” which offers the new collection’s only direct link to Jesus’ Son, referencing the character of Dundun—there’s a story named for him in the earlier book—and (perhaps) told by the same narrator, traverse familiar territory (drugs and redemption, mostly) with an unforgiving edge. In the former, an addict, struggling through the first days of recovery, composes unsent letters to his loved ones, a project that grows increasingly unhinged. “Dear Satan,” he writes late in the story. “You think I didn’t recognize you that time?” Again, the metaphoric, the symbolic, blurs into the actual, and the world becomes a miraculous, if terrifying, place. “Are you a messenger of God?” the addict asks; “Worse,” is the reply. “What,” the narrator wonders, “could be worse than a messenger of God?”—a response that recasts the moral arc of the universe as one of doubt. This echoes Robert Stone in his 1996 story “Miserere,” in which an anti-choice activist disdains the priest who refuses to bury the aborted fetuses she steals from a clinic: “Oh Frank, you lamb, what did your poor mama tell you? Did she say that a world with God was easier than one without him?… Because that would be mistaken, wouldn’t it.” God is never easy. It is a burden, as much as a consolation, to believe. Such a realization emerges most awfully in “Strangler Bob,” which takes place in jail and resolves around an unexpected reckoning: “Very often I sold my blood to buy wine,” the narrator tells us. “Because I’d shared dirty needles with low companions, my blood was diseased. I can’t estimate how many people must have died from it. When I die myself, BD and Dundun, the angels of the God I sneered at, will come to tally up my victims and tell me how many people I killed with my blood.”

Here we see what makes Johnson transcendent: the collapsing of the boundaries between good and evil, right and wrong. Over the course of the story, we have been seduced by the narrator, his travails, much as we are in Jesus’ Son. Then, in the final line, the final sentences, he flips the narrative dynamic, leaving his readers no longer sure what to do with our reaction, how to hold the complexities, the complications, of the human soul. Weakness and strength, self-delusion and self-awareness, they swirl through every heart and head. “He was in the middle of taking the last breath of his life before he realized he was taking it,” Johnson writes at the end of his first novel, Angels, imagining the execution of his protagonist, a petty hood turned killer named Bill Houston. “But it was all right. Boom! Unbelievable! And another coming? How many of these things do you mean to give away? He got right in the dark between heartbeats, and rested there. And then he saw that another one wasn’t going to come. That’s it. That’s the last. He looked at the dark. I would like to take this opportunity, he said, to pray for another human being.” Is there redemption in that moment? Yes, and also not exactly, which is, of course, the point. Houston dies, as he must; nothing will save him, not even that resting place between his breaths. And yet, he also comes to life again, twenty-four years later, in Tree of Smoke, which touches on the story of his earlier life without ever really telling it, much as “Strangler Bob” reflects “Dundun” while also keeping it at a distance—or is that the other way around? “It doesn’t matter. The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.” Time is circular, or fluid, it continues to reverberate even after it is over, which means that the space between heartbeats is the only place we ever live.

Angels is Johnson’s first work of fiction, published after three volumes of poems. This makes it a bookend of sorts to The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, and I’m struck by just how closely the movements of the books align. Each involves the tension, or the balance, between revelation and degradation, the sense of enlightenment in the most human, or natural, events. “He preferred to wrestle with his torment,” Johnson writes in “Triumph Over the Grave,” “sitting up in bed, pivoting right and left, putting his feet on the floor, hunching over and rocking, curling into a ball, straightening out on the bed, lying east, lying west, no position bearable for more than a few seconds—more active in this single afternoon than I’d seen him in the last two months put together—and he wanted no help with this.” The moment is, at once, intensely physical and intensely spiritual, emblematic of the requirement “to live each incarnation to the last natural breath.” Something similar unfurls in “Doppelgänger, Poltergeist,” in which a graduate student grows obsessed with a conspiracy theory involving the murder of Elvis Presley and his replacement by the twin brother, Jesse, who was reported to have died at birth. Ghosts again, or demons, manifestations, faith and loss of faith. “God, see what we’re doing to each other down here,” a man cries out on a Manhattan subway platform the morning of September 11, 2001, as the World Trade Center towers collapse overhead. The moment is myth but it is also reality, while also rendering such distinctions moot. “It might easily have been that day,” the narrator observes at another point. “I’m only guessing. So what? The Past just left. Its remnants, I claim, are mostly fiction. We’re stranded here with the threadbare patchwork of memory, you with yours, I with mine.”

You with yours, I with mine. There it is, the only option. “The masquerade continues,” Johnson insists in the title story, writing from the perspective of a retired advertising executive, one of the more settled protagonists in the collection, although the real message is that we are never settled, no matter what we do. From jail to the classroom, from the suburbs of San Diego to the hill country outside Austin, we are all alone together, adrift in a universe that is at best indifferent, in which every moment might well be the last. “I wonder if you’re like me,” he conjectures, “if you collect and squirrel away in your soul certain odd moments when the Mystery winks at you.” This has been among the central messages of Johnson’s writing since The Man Among the Seals, his first book of poems, appeared in 1969. “i wonder about everything:” he writes there, “birds / clamber south, your car / kaputs in a blazing, dusty / nowhere, things happen, and constantly you // wish for your slight home.” The Man Among the Seals has just been reissued, in an omnibus edition with his 1976 collection Inner Weather, and it’s instructive to revisit if only as a reminder of the consistency of Johnson’s themes. His voice is that of someone lost in a world that both beguiles and bewilders, where even the simplest acts—waking up, say, or going to work—can turn terrible or profound, where the most trenchant experiences are also fleeting, where meaning and the inability to discover meaning are two sides of the same coin. “We live in a catastrophic universe—not a universe of gradualism,” a character insists in “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden”; as to what this means, Johnson makes it clear a couple of pages later when his narrator describes his wife: “She’s petite, lithe, quite smart; short gray hair, no makeup. A good companion. At any moment—the very next second—she could be dead.”

Again, we return to the contradiction, to the literature of last things. It doesn’t matter. The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.

Two days after Johnson died, I wrote an appreciation for the Los Angeles Times that began with my desire for him to have been exempted, to have been, in some way, spared. Wishful thinking, yes, and antithetical to his work, in which death (or the Mystery) is always just behind the veil. Still, if The Largesse of the Sea Maiden has anything to tell us, it may be that such a thought is not so wishful, that a porous boundary divides literature from life. The living line of language—it’s our consolation and our limitation. It’s the space between the heartbeats and the breath. It felt wonderful to be alive to hear it! I’ve gone looking for that feeling everywhere.