My father recently lost a toe. The second one on his right foot, lopped off in an outpatient procedure, quick and painless. Such a funny thing to lose, everybody thought—my mother, sisters, brother, the grandkids all finding much levity in the situation. They call him “Nine-toed Joe” now, and for his birthday his granddaughters gave him customized white tube socks, the ghoulish gap of his little amputation rendered with a red Sharpie. My father found the gift hilarious, and wore the socks proudly with his new sandals right through to Halloween. I laughed, too, pretending not to find it disturbing and macabre. His toes had become grotesque with old age, as toes do when you approach eighty, after decades of punishing footwear: Army boots, oxfords, wingtips, Chuck Taylor Converse All Stars on the basketball court, running shoes in which my father pounded the pavement, training for marathons he never ran. Now he’s barely able to get any shoes onto his feet in order to make it to church.

When I learned about his impending procedure one spring, in a text message from my sister, I called my father immediately to protest. He told me not to worry. Don’t even think of making the trip up.

“Dad, don’t do it!” was all I could say, but I couldn’t convince him otherwise. It was his decision, he said. It wasn’t up to me.

Yes, it was only a toe. And my father was happy to see it gone. I knew it came as a relief for him to part with this small piece of himself, a hammertoe that had rebelled against his foot and gait and quality of life. In old age it had curled over the big one, a wayward appendage abraded by the straining leather. It was painful, sure, though he’d brushed aside my concern as he limped and shuffled and walked on the outside of his foot to alleviate the pressure. Eventually, he’d abandoned shoes in favor of some yellow Crocs I bought for him. The rubber slip-ons were all he could wear comfortably, even in winter. He seemed to me a frail old man waddling on platypus feet. “Time for some relief!” he assured me. “I’m ready to move forward.”

The older I got, the more sensitive I was to his rashness, his apparent lack of foresight, and the complete deterioration of a social filter. As the firstborn, in many ways I had become the parent and he the stubborn child. I knew what was best for him and was not afraid to say it, so we were more at odds now than we had ever been. I could be unbending and pushy. And he liked to get my goat. For example, when being seated in a restaurant, he would dawdle and stray from the family, walking up to random patrons mid-bite, who were perplexed by an oversharing old coot shouting at them above the din, introducing himself as “G.I. Joe” with a fist bump. He’d then launch into stories about KP duty in the mess hall clearing greasy trays and cleaning the latrine. Growing up, we muzzled him with eye rolls and protests, so he repressed these harrowing tales. He’d waited his whole life to tell his Army stories ad nauseam, and he didn’t care now who heard them. People were sometimes charmed, but just as often taken aback. I would rush over, hook arms, and whisk him away like a failed vaudeville act getting pummeled with vegetables. “Gratias ago tibi,” he’d rattle off in Church Latin lingo. “Procedamus in pace.” His signature sign-off, an inscrutable punchline drawn from seminary days (which he jokingly called “the cemetery days”). He was suddenly a comedian in a cassock, pre–Vatican II, bowing and taking his leave. It was his schtick, a tiresome, incongruous persona. My father thrived on it; I was used to it, even though I knew his behavior was amplified by my impatience. Why couldn’t I just let him be?

When I called to check in several days before the scheduled surgery, he boasted, “I’m still above ground and vertical!”

“It’s the vertical part I’m worried about, Dad.” I was being a spoilsport with my doubts and protests. He was perplexed by my gall, my ill humor. I couldn’t get over myself, apparently, and seemed to be the only one in the family to experience a real sense of loss. I refused to let it go, no matter how beneficial the surgery was supposed to be.

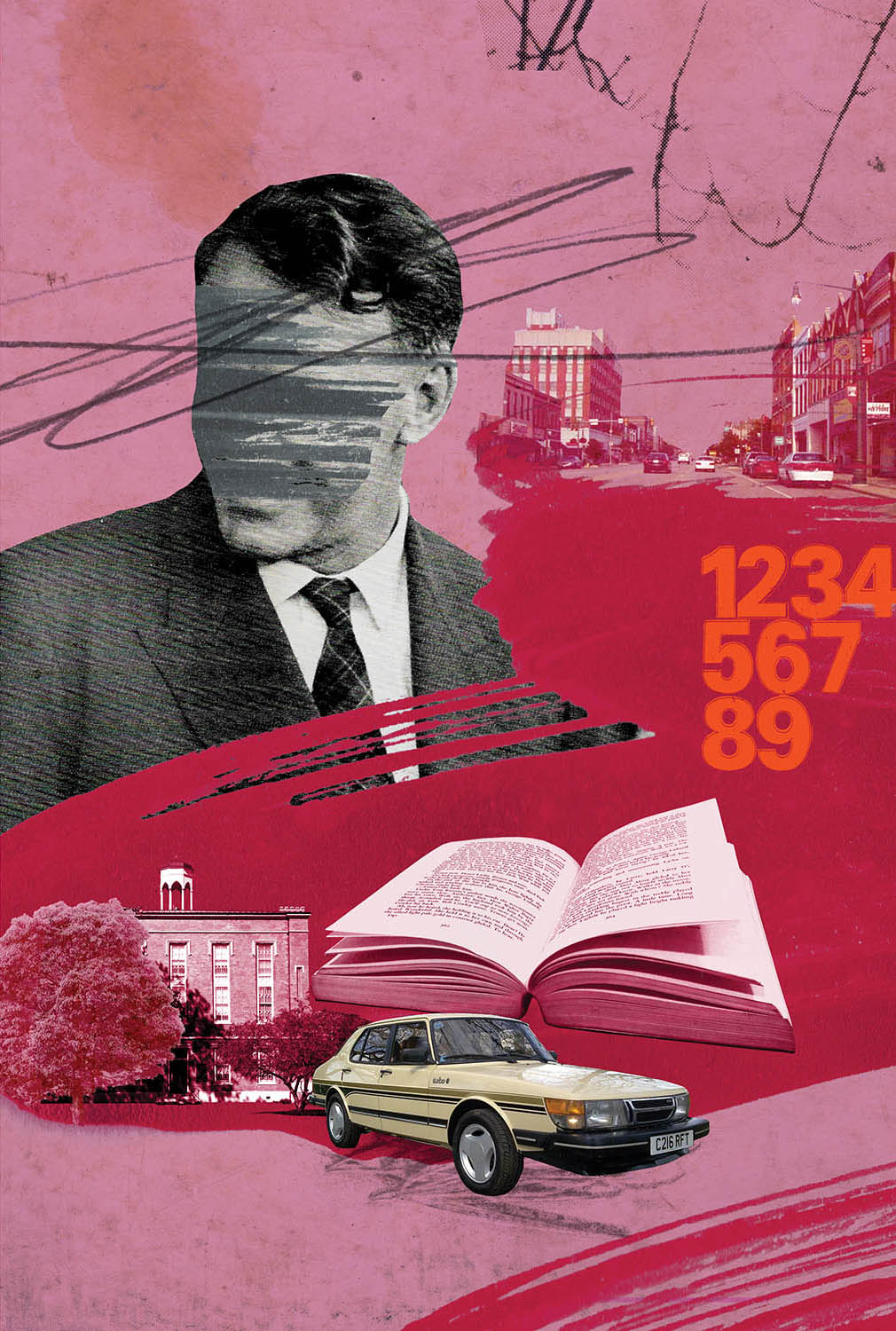

But I was there for him, at least. There, but not there, teaching at a college in his hometown of Galesburg, Illinois, two and a half hours from the suburbs of Chicago, where the whole family had gravitated. The college was my own alma mater, and having returned there, I now felt stuck in a place that was all too familiar, a town where there seemed to be more trains than people. I had gratefully accepted an opportunity to switch careers and teach at this leafy, isolated campus, escaping the fickle, unrewarding world of publishing in New York. But I just couldn’t reconnect to this place, second-guessing my choices in the middle of the night as Burlington Northern engines plowed through town five, six, seven times an hour—heading out, heading in, horns clashing like Charles Ives’s marching bands at Putnam’s Camp half a block from my tumbledown apartment, leaving me as rattled as the drafty windowpanes.

And my hand-me-down car had lost a front wheel. My father was squarely against my buying the car from my brother-in-law in the first place, saying it was too old, that it had sat in the driveway unused for too long. “But it’s a Saab!” I argued. “They run forever.” Little did I know that a ball joint would fail while exiting a liquor store parking lot on New Year’s Eve, and I would find myself directing traffic around the collapsed heap, soberly awaiting a tow truck and advice from Dad about where to get it fixed. Afterward, I developed a phobia of wheels coming off while taking exits too fast or when bumping over rough crossings as the gate came down. I had nightmares about flying over guardrails and falling off bridges. So driving to see my father wasn’t easy. Often I just stayed put.

To say he lost a toe—like losing his keys or his marbles—is a misnomer. It wasn’t lost, but taken from him. It was removed hastily at the urging of a young specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital with whom Mary, my father’s older sister, had set him up. Mary was a retired RN who had worked in the maternity ward there. She lived nearby in a Michigan Avenue high-rise, looking down on the Water Tower, a steadfast castle disguising an antique standpipe that survived the Great Chicago Fire. My father met with the surgeon for ten minutes, tops, and was told that he would be better off without the toe. At his age, fixing it wasn’t worth the trouble. “After all, you won’t be running any more marathons,” the surgeon joked. But my father used to aspire to this, back when he was a daily runner: slow and steady, always willing to go the distance, once completing a half marathon in just over two hours. (“Not too shabby,” he’d bragged.) Now Mary was the lone jogger in the family, heading out, at seventy-nine, to brace the sharp winds along Oak Street Beach in black tights and a baseball cap with her iPod and the soaring inspiration of Andrea Bocelli singing “Ave Maria.”

“Oh, Joe. Get rid of it!” Mary insisted. “You’ve got plenty of others. This is one of the top orthopedic guys here. You don’t know what strings I had to pull on short notice.”

“You won’t need it anymore,” the surgeon agreed. “It’s too involved and painful to straighten it out. Let’s take it off.”

My mother, who was also a nurse, had surprisingly little to say in the matter, apparently hoping for the best. She was timid and halting, and I was dismayed by the way she described the consultation on the phone without her usual circumspection, as if the decision had come from on high. My mother, who still did the grocery shopping, wrote the checks, and complained as bitterly as I did about my father’s driving. Mom, who yelled at my father when he wore running shoes to church. It was mostly his bossy older sister’s doing, I gathered, because her influence was undeniable. When Aunt Mary was on a tear, you stepped aside and let it happen. They’d scheduled an appointment for the procedure two weeks later, and that was that.

I wasn’t having it. Why should he give up a part of himself at his advanced age when I knew full well the surgeon was wrong? I knew Dad’s toe could be straightened and fixed, because I’d gone through the procedure myself. In my thirties, a neuroma was excised from my right foot after years of steroids and alcohol shots to kill the inflamed nerve. The same toe, in fact, had to be realigned and set straight because the nerve had swelled to the size of a marble and pushed my toes apart, disfiguring them. (My father probably had a neuroma too—and had had one for years—so why hadn’t it been diagnosed?) During my surgery, the second toe had been threaded through with a wire that protruded out the end, which I stubbed almost daily afterward. The wire was removed after six weeks, with small pliers, and then with bigger ones when it bent and got painfully stuck. The podiatrist began to panic as I assumed my poor toe was a goner. All this was done without a drop of anesthesia. My back arched in the examination chair and I envisioned myself on the silver screen undergoing the horror of electroshock therapy as the surgeon tugged, twisted, then yanked and I cursed at him with abandon. It was an unimaginable pain, but worth it, I decided, even years later as severed nerves still caused numbness and discomfort. I shared a few of the gory details with my father.

“I’m no spring chicken,” Dad said with a wave of the hand, my sanitized version failing to sell him. “I’m not going through all that.”

My father announced his decision to the world: to the priest who shook his hand after Mass, to the mailman, to the busty trainer in a sports bra who flirted with him at the gym. To his buddies Lyle and Ron and other random neighbors strolling by with their dogs. To his grandkids, who squealed with horror and delight, running wild in the living room as he wriggled his deformity at them.

In most respects, it came as a relief to my family, reassured that he would regain stability, especially after taking two spills that worried us. The first happened in a Walmart parking lot, where, blinded by the glare of black ice near the entrance, he fell and scraped his nose and broke his glasses—a bit bloodied but fine—and was then promptly ushered inside by a manager and given a free pair from the Vision Center. Not long after that, he fell in the hallway of a local high school, where he worked as a substitute teacher. Dodging throngs of students after class, he stumbled into a young girl and wrapped his arms around her, which kept him from going down. He later was accused of “inappropriate hugging.” The assistant principal regretfully let him go, saying, “You know, kids these days. We can never be too careful.”

When I was young, my father was one of the clumsiest men alive, constantly nursing cuts and bruises from various “minor” accidents. He once had a run-in with a fallen yield sign that he attempted to hurdle while jogging through weeds on the side of the road. I remember sutures on the hairy shins of our would-be marathoner who trained precariously after dark. He would often venture out after dinner, bundled in sweats and a stocking cap, to run late into the night. Once my mother called the police to send a search party after him. He turned up well past our bedtime, his face covered in a Vaseline death mask that protected him from the elements.

Another example: As a teacher’s kid, I accompanied my father in his official capacity to a high school basketball game, where he greeted every person he passed, forgetting to pay attention to what his feet were up to. Keeping his eye on a long shot as it swished through the net, a flash of glory went through the former star guard’s head, perhaps—the game-winning basket he made with seconds on the clock that won the 1955 regional playoffs for Corpus Christi High—and he tripped, falling into the stands, eager helping hands righting him courtside amid a wave of catcalls and cheers. I faded into the stands as he took a bow.

In a way, my father was a master of falling, a skill he acquired early in Army boot camp, where he learned to “tuck and roll.” Taking a tumble became a maneuver for him, a comedy routine that left few in stitches except sometimes himself.

Even less comical was his driving, which was endangering others’ lives. You see, he had recently been in three scrapes in two months—the first involving a sideswipe with a teen driver whose parents’ lawyer was still threatening to sue. More recently, he’d lost control in a parking garage, on a spiral exit ramp, and hit the wall, messing up the front end paint job pretty badly. “I got a little dizzy,” he defended himself. “No big deal. Don’t you ever get dizzy?” The real problem was that my six-year-old niece was riding in back, belted up safely, thank goodness.

At the Olympic Star, a Greek restaurant where he got happy fist bumps from every waitress, we ambushed him about his bad driving. We threatened to take away his keys, my brother said he no longer wanted his children to ride in his car. He even lobbied for assisted living for both of our parents if my father didn’t listen and comply. We demanded he take a driver’s test every year. We commanded him to be more careful, to pay attention and stop gawking at everything. He was putting others at risk, including anyone who rode with him up front in the “death seat,” as he called it when we were kids, singing “Buckle up for safety, always buckle up!”

We threw way too much at him that day, and he shut down. “You can’t take away my autonomy— I’ll die! Damn you all, I’m a good driver.” We didn’t take issue with his flimsy justification, because how could we? He had driven us there, and I wasn’t about to hijack his keys. So we backed off and let him drive us home.

One hurried, icy morning, a phone call from my mother reminded me of the dreaded procedure. “He’s out of the hospital and we’re headed home!” Mom said.

“Don’t look now, but Momma’s driving!” my father croaked in the background. I heard banging and fumbling and hoped they hadn’t ended up in a ditch.

“Dad?” I said, waiting as patiently as possible.

“Nine-toed Joe here,” he said finally, groggy but clear. “How are you?”

“The question is how are you?”

“Among the living!”

“So I guess it’s gone, your toe?”

“Gone but not forgotten.”

“Are you in pain?”

“Not one bit. Got my Vicodin, and your momma, the lovely nursemaid I absconded with, she’s here to tend to my every need.”

“Are you sure it’s the next exit?” I heard my mother ask, imagining her gritting her teeth and rolling her eyes.

“Take whatever one you want. My life is in your hands.”

“You see what I’m up against here?” she said, directing her exasperation at me. I tried to laugh.

“Joe! I need you to focus.”

My mother didn’t usually drive, and the expressway made her especially nervous. Despite this, she was a fine driver and had never once had an accident, while my father’s fender benders accumulated. Their gold Accord was a palimpsest of gouges and touch-ups, with a shiny front quarter-panel replacement that reminded us all of why they should never buy another new car.

I couldn’t help but think of the time he barreled out of my sister’s driveway in reverse, hitting the gas instead of the brake, plunging backward into a ravine. Or the morning he spilled orange juice into his pill organizer and downed a colorful clump of his nightly Klonopin. Thirty minutes later, he conked out at the wheel, but my mother snapped to attention, steering them to safety on the shoulder.

I imagined my mother white-knuckled with trepidation but managing well. In a Vicodin haze, with his thickly bandaged right foot, Nine-toed Joe was obviously in no shape to touch the pedals.

“Your mother is a crack driver,” my father said, still loopy and solicitous.

“And you’re a crackpot,” she shot back. “Pay attention to the GPS, please.”

My mother slipped into nurse mode. She described their morning and the procedure, said a few words about the surgery, the bandages, how it all went as planned. She said he’d be up and walking around in a matter of days.

“Did they put it in a jar for him, at least?” I joked. “Does he get to keep it?” I pictured the ghastly yellowed thing with its neglected nail floating like a prawn.

My mother laughed. She reminded me of the tonsil my brother once put on the shelf in our shared bedroom. Sad, she said, that they don’t preserve things in jars anymore.

I tried again to reassure myself: It was only a toe, something insignificant. Too late to lament its disappearance. And I’d missed my chance to rally to save it. At least he might avoid another spill and another kyphoplasty, cement injected into his beaten-up spine. At least it wasn’t an angioplasty, or any other plasty. It wasn’t the heart, propped up with seven stents as it was already. It wasn’t another polyp taken from his colon, or the colon itself, which we feared last year he might lose until we found out the blockage had been an impacted bowel, just needing a bit of irrigation. So much to be thankful for. He was still around—but just beginning to disappear.

It was nearly ten o’clock and I hadn’t finished prepping to teach my morning class. I still had several pages to read before heading to my car to make sure I didn’t have to walk to school if it didn’t start.

I made it to class on time, but unprepared.

We were looking at E. B. White’s essay that ends suddenly with the narrator viewing his son, about to swim in the lake, as he pulls on his cold, wet trunks and winces as they cover his “vitals.” The father is disoriented as his boyhood experiences blend in with perceptions of his son’s, but certain clues betray the passing of time—his yearning for the tracks left by horses’ hooves on the dirt road now marked by the ruts of automobile tires; the “nervous sound” of the outboard motors jarring the once-serene lake. And the essay’s last words: “the chill of death,” a truncated line that frustrated my students.

“It’s depressing,” one of them complained. “Puts me to sleep. Plus it cuts off, like he wasn’t finished.” A wave of nods and grumbles.

“What isn’t depressing?” I asked. “When you choose to look at it that way, you shy away from something deeper. Look at what has disappeared! Does it matter what we lose? What belongs to the father here, and what is really the son’s?”

My students remained silent.

“Okay,” I continued, “is the father depressed? I don’t think so. No, he’s just closer to death, and himself. He is not his son, see, and that’s just how it is. They’re divergent.”

Then I threw in: “Why, this morning my father just had surgery and they chopped off his toe. But he’s happy as a clam!” I laughed, my voice bouncing off the high ceiling. I offered no further explanation. I got aghast looks, looks of disgust, looks askance. Even the boy who always made an effort to participate screwed up his face, his look verging on incredulous.

My father and I were about as divergent as could be; our personalities couldn’t have been more opposite: I the far-flung, finicky son who needed my space and he the provincial man-about-town who came at life as if it were a rollicking family reunion with relatives he’d never met before. My real home was in Brooklyn, a city I had left half a country away, not here, where my father kept daily tabs on the obituaries in the Galesburg Register-Mail just to see who’d been lost in his absence, and where I felt about as far away from him as I ever had.

I am my father’s son. But so what? I feel the push to get closer to him and the instinct to let him go. Why push, when two people are so fundamentally different, even incompatible? Why not just accept our stark differences for what they are rather than forge a new bond with him now, so late in life? Why the need to tell a story about this would-be priest, this soldier, this counselor and teacher, this lovable goofball I continually resist loving? I think of his toe versus mine: one gone, the other intact. Our feet on the same ground walking the same daily path. As father and son we merely overlapped, and that is all.

Denny, a frizzy-haired blond, continued to eye me with suspicion. I wanted to call on him, but didn’t. We had forged a rocky connection; he was intense and unfiltered, had a real desire to write, and he liked to snag me after class for labored side discussions. He was pragmatic, athletic, a political science major. He had a lacrosse scholarship, loved his mother fiercely, and hated his father, who lived in Perth, Australia, “the most faraway place on Earth.” I recalled these details vividly from a story he was struggling to write. He had seen his father only once since he was eleven, in an awful Chinese restaurant where his dad brought his new girlfriend. Rubber-banded lobsters knocked against aquarium walls by the front counter, and the narrator wanted desperately to turn them loose before he made his own break for home. Denny was good, I thought. He had vision. Whether or not he actually ever saw his father again, he just might find him someday if he kept writing.

Today Denny didn’t say a word. “I get it!” a girl from Queens said. “It’s an ah-ha! moment. Like what Oprah says.”

“It’s a moment. I’ll accept that.”

I looked at the clock and was shocked that there was only a minute left in the period. In the sudden din of stacking and packing and chairs being pushed back, somebody asked why we didn’t read Charlotte’s Web instead.

“I love that book!” the others chimed in. “Or what about Stuart Little!”

The class was over. As I dismissed the students, I also tried to dismiss a nagging sense of failure. Denny approached me as usual. I was surprised, given his silence.

“Is that true, what you said? About your dad’s surgery?”

“Yeah.”

“Why did they take off his toe? So strange.”

“Because he couldn’t walk. He kept falling down. And scaring the living daylights out of me and my family.”

“Weird.”

“You can’t make that stuff up.”

“I think you should write about it.” He slung his backpack over his shoulder and turned away, lumbering through the door. There was a soft light behind the frosted-glass transom—Room 201, where I had once sat on the other side of this very table, scrawny and suspicious and, if not exactly like this boy, then certainly every bit as curious.

I left the classroom humming. I had made connections, I told myself, though with whom I wasn’t sure. I walked lightly toward the outskirts of campus, along the frozen brick path. I was wearing penny loafers, the wrong shoes for winter, certainly—but the easiest to slip into at the door in a hurry. I wore them so much they were scuffed irrevocably and almost unnoticeable on my feet. I felt numbness, not pain, where some nerves to my toes had been cut. But I was sure-footed.

I followed the path’s arc. This might have been the same path my father and his sisters walked on their way to school, bulldozed into a parking lot for the church our family attended when I was younger, where Saint Crescent—a child saint, martyred at the age of nine and delivered by no small miracle from Rome—was enshrined. The boy saint’s protective powers were legendary in these parts: This was a city in Tornado Alley, where storms had devastated nearby towns, though Galesburg itself had been spared a direct hit for more than a century.

As I emerged from a grove of cedars, I passed in front of the church, whose steeple seemed to move against the clouds. It was the tallest thing around; looking straight up at it made me dizzy. This shingled needle with its cross had become a part of my daily route—a compass, indicating a place my family called home. They all lived elsewhere now, and I was just passing through.

Crossing the disintegrating asphalt of the church parking lot where the old high school gymnasium once stood, I thought of Uncle Cub, my father’s best friend and teammate, who married his sister Bonnie. From Dad’s old yearbooks I’d filed away several images of them together—my father, the skinny guard, and the more substantial Cub, a forward, all shoulders and grins; Dad sinking the shot that pulled off the win, just before the buzzer, making it to the playoffs but not to state. Cub was always there, clearing the way for him. He was always kind, contemplative, always puffing on a sweet-smelling pipe. But not too long ago, he’d slipped away, piece by piece, as he succumbed to blood cancer. Gangrene took toes, a whole foot, legs below the knees. After that he disappeared all too quickly, too gruesome an end for a gentle man—a social worker, a professor, a man who spent his last years working late, visiting the poor and infirm, even when he himself was ailing.

At the far end of the lot, I saw Denny again, outpacing me. How had he gotten so far ahead? I quickened my steps through the old snow, hoping he might hear me and stop, and lost my balance, falling backward. A blow from behind left me fighting for breath. I was staring at the sky. I saw trails of a faraway jet, the pinprick of a star, and the steeple. Black ice was to blame, slick beneath the packed snow on the parking lot. Stupid shoes. I was on my back, head against my tote bag.

I heard crunching, coming closer, as my breath fogged my glasses. I spotted a book a few feet away, my teaching copy of E. B. White in a drift of snow. Denny was quick to dig it out, fan the snow from the pages, hand it back to me.

“Are you okay? Man, you took a tumble! Did you hit your head?”

“Nope,” I said, brushing off. “I’m good.”

I stuck the book back in and patted the canvas bag. “Saved by a stack of ungraded essays. Yours is at the top.” I was flustered, dizzy.

“Funny,” he said. “So you’re sure you’re not hurt? I can call Campus Safety—”

“Not at all. Not a bit,” I claimed, though my vision was skewed. The brown spots obscuring Denny were disappearing. “Just need a moment. To get my bearings.”

“I’m not just gonna leave you here.”

“My car’s right there,” I said, pointing.

He looked over and studied it with surprise. “Cool old Saab,” he mused. “Too bad they don’t make them like that anymore.” It was sagging a little to one side, its yellowed headlights misty.

“My dad had one,” he volunteered, hesitating. “The only 900 Turbo in town. It was a convertible, dark red, with a steering wheel bigger than I was. I loved it with the top down. I loved going fast.”

“Well, mine’s ancient. And doesn’t like to go fast.”

“Hold on to it if you can,” he said. “Might be worth something someday.”

I thought of the front-end damage and the leaking radiator and laughed. “Whatever you say.”

“Glad to see you’re on your feet. Word of advice? Get yourself some boots!” He checked his watch and said goodbye, trudging ahead as I swatted at the snow. I’d meant to ask where he was headed, but it was too late. The moment had passed. He was off.

I never saw him again after the semester was over, when I would learn from a colleague that he had transferred, much to his coach’s dismay. In a year I was no longer stuck in that place, and neither was he. We had both moved on, back east, or west, to another continent or a place called home, wherever it may be, each attempting to catch up to ourselves.