Recently, rewatching The Commitments (which I’d last seen at the tender age of thirteen), I found myself thinking again about what a strange road it has been—for Ireland; for the world. That movie—based on a Roddy Doyle novel about a Dubliner who insists on forming an ill-fated but spirited soul band—came to cinemas in the US two years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and seven years before the Good Friday agreement, which paved the way for peace in Northern Ireland and Ireland more generally. The Commitments is full of a 1990s sensibility. The city is scarred and there are horses in the vacant lots, but soul music is coming to Dublin. Soul is going to be a new vessel for singing old pain and buoying up joy. The world of the movie is open to heady reinventions, which in its tellings seem somehow more hopeful than mere appropriation, more artful than mere global capitalism. When I first watched The Commitments, in 1991, I had just been liberated from a childhood spent performing Reagan-era arms-race drills by huddling under various elementary-school desks in California. We’d vanquished the Russians and we seemed ready to be done with borders. Our whole world seemed about to tip toward something happier and more international, a high-speed blur which seemed like it might be a good in itself, which might yet lead to peace and prosperity for all. It’s worth remembering how parts of the nineties had a kind of blinking freshness to them. Francis Fukuyama told us history was over. We lived in the thrall of possibility.

The Northern Irish poets who were born and grew up in the 1990s came of age amid the relative hopefulness of the Good Friday agreement, which arrived in 1998 and brought the hope of a lasting peace to Northern Ireland. Indeed, the 1990s radically transformed Ireland and Northern Ireland, though at times change came at a snail’s pace. It’s perhaps a measure of the success of the peace that many Americans these days have forgotten that Ireland and Northern Ireland are actually in separate countries. In the 1990s, we had good reason to remember: For years, the Troubles—essentially three decades of civil war between Catholic and Protestant paramilitaries—had been on. Bombs erupted frequently in Dublin and London, but violence was particularly intense in Northern Ireland, six counties on the island of Ireland that are still part of the United Kingdom; where Protestants (whose history there partakes of a long colonial presence) and Catholics (who have multiple reasons to resent this thousand-year history) have rarely, if ever, lived comfortably together. The roughly century-long presence of two countries on one island has itself been deeply uneasy: After what is now the Republic of Ireland had acquired its own independence following the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921), the situation of Catholics in Northern Ireland remained poor. Tensions were high: By the late 1960s, what had begun as a civil rights movement morphed into violence that continued grimly on for decades: bomb by bomb, death by death. To get a sense of how the Troubles felt in 1971, as they were beginning, Seamus Heaney wrote of Belfast:

I am fatigued by a continuous adjudication between agony and injustice, swung at one moment by the long tail of race and resentment, at the other by more acceptable feelings of pity and terror…it hasn’t been named martial law but that’s what it feels like.

Heaney, of course, is not a soul singer, but is the Irish poet who has most consistently brought Ireland’s poetic music to audiences in the US. Even though in 1972 (after a year in California) he moved to Dublin, he was born in the north and began his career in Belfast. In Belfast, Heaney had initiated and been initiated by a remarkable group of poets who continue to forge Northern Ireland’s music, to echolocate its struggles in verse. Heaney’s work arises of this place and through its struggles; even in the face of prolonged colonial reality; even while writing in the colonizer’s tongue.

Behind Heaney is an entire field of poets. In Heaney’s time they worked together, often meeting for biscuits and tea in a brick row home around the corner from Queens University. Many still work together, and as they do, Northern Ireland seems to produce, per capita, more terrific poets than any region of 1.8 million really has a right to. It seems sometimes silly how many good writers live there. It may be something in the water, or, as Heaney’s dear friend the poet Michael Longley said when I had lunch with him, a bit like entering a jet stream is for birds—“when you enter it you just seem to fly faster.” Belfast remained (and even now remains) home to Heaney’s roughly contemporary and slightly younger colleagues Ciaran Carson, Frank Ormsby, Medbh McGuckian, Longley himself, and Paul Muldoon (who left for America). This generation has been followed by poets Leontia Flynn, Sinéad Morrissey, and Nick Laird, among others.

These poets are all good ones to learn from as we face down some deeply American troubles now. Belfast writers know about writing into difficult times. Carson’s Belfast Confetti is a landmark that I think every American poet worth their salt should look over. Anna Burns’s Man Booker Prize-winning Milkman is a remarkable study of the inner claustrophobia of living in a war zone. In conversation, people pass their own stories along when they have a mind to: Driving around Belfast with Glenn Patterson, current director of the Heaney Centre, and a fiction writer and a lapsed Protestant, he casually mentioned a childhood of never quite being sure whether his parents would come back when they left; of scaling curfew walls for thrills as a teenager; of the time in high school when a bar known for serving liquor to minors was bombed. Everyone knew the next day who’d been out drinking, he said, because they turned up at school with bandages on. The story was told with some wit, so we laughed, despite the violence at its core.

There is still quite a bit of violence at the core, even though it’s been held at bay for a while now, long enough for a crop of kids to grow up relatively unscathed and make their way to university. On that path, many of Northern Ireland’s (and indeed Ireland and the UK’s) young poets still do find a path to Queen’s University Belfast, and enter the slightly slanted maze of hallways and offices that compose the Seamus Heaney Centre, where Carson still leads a Friday workshop, and where Longley teaches occasional summer classes. The poets coming up in Northern Ireland still work through new poems over tea and biscuits by day, and talk about them over more than a few beers or gin and tonics by night. They stage readings in bars around town and publish pamphlets (Stephen Connolly’s pamphlet series is something of a wonder). Their music is both old and new, rooted and experimental. There is both a wisdom and a hopefulness about them: They’re both citizens of the world and of the EU, of Ireland and of the UK, and also of a deeply fractured, long-contested place, which at least offers the benefit of knowing how quickly its hard-earned civic life could shatter again.

In fact, it’s as if the peace itself is a kind of character, moonlighting in the air, a kind of Robin Goodfellow, crafting (for a while now) the good or goodish dream. One thinks of it this way: The peace is younger than these poets; this past Good Friday, the peace turned twenty; this coming Easter, the peace will have reached a legal drinking age in the US, though it would have been able to drink legally in the UK a few years ago. (Whether the peace could truly drink its health is entirely a different matter.) The peace was, as long as we’re really thinking about the 1990s and its characters, accomplished with some help from Bill and Hillary Clinton, who sensed on their visit in 1995 that this accord might yet be possible. People in Belfast still talk fondly about the Clintons’ work—how Hillary talked tirelessly day after day to Protestant and Catholic women’s groups and marched up and down various corners of Belfast known for sectarian violence—the Shankill, which is Protestant/Loyalist; the Falls Road, which is Catholic/Republican/Nationalist. Even now, inside the looming, otherwise unremarkable-looking Europa Hotel on Belfast’s Great Victoria Street, an upper room is named the Clinton Suite. Across the street is the Crown Bar—dating from 1826 and listed by the UK heritage group the National Trust as a National Landmark—where you can eat in carved-wood booths, under Victorian gas lamps flickering with actual gas, while a woozy but cheerful scene swims on a dark mirror that has been pieced together and rehung after a bomb.

That glass in the Crown Pub seems rather like Belfast itself—pieced together, rehung, and allowed a ginger, careful ongoingness. Over lunch there two springs ago, Michael Longley and Frank Ormsby told me the Crown had served the same bangers and mash for as long as they could remember. (“It’s not the cordon bleu,” said Frank. “No, no! It’s more the cordon yellow,” Michael added). Cuisine aside, I left Belfast aware that peace, such as it is, is never simply a passive force, ongoingness notwithstanding. The very art of civic life must be crafted, and sometimes rehung, hopefully with at least a modicum of the care that goes into making a poem. Perhaps that is why there are now so many festivals in Belfast—book festivals and music festivals and theater festivals and science weekends. There are arts spaces in abandoned churches and schools. It may be that the UK is more generous than the US in arts funding, but it’s also worth noting that in the absence of fighting, the city has been aware that it must actively weave people together.

In any case, the peace forged in the Europa Hotel ushered in a promise—of demilitarized borders, easier flow of people across nation states, of widened political and economic and cosmopolitan life. A promise, that is, that seemed much like the rest of the promises of the early post–Cold War years. Yet my time in Belfast made it pointedly clear to me that no peace is an island: The peace’s very growth was intertwined with the growth of the EU. Years of border checks and border violence involving Northern Ireland and the southern counties of the Republic of Ireland had softened into a kind of Irish “don’t ask don’t tell” policy. In Northern Ireland this freedom was not the same as, say, the freedom of gay marriage or the freedom to have an abortion locally. Neverthless, it did sanction a greater fluidity at least in one’s citizenship. For those who chafed against UK and Protestant rule in Northern Ireland, the new agreement offered wiggle room against a painful colonial history. Others had literally spent years smuggling small items across the border from the Republic. Then suddenly no one checked. And international companies could suddenly invest in Ireland and Northern Ireland easily and at once. Amid these developments, there was simply the fact that you could walk around town again. As Patterson told me, “I had a sense that things were changing when they started to put glass in the downtown windows.”

There’s a lot of glass in Belfast now, though Patterson was quick to point out as well a phone booth where an explosive device filled with nails had detonated—a “nail bomb,” he called it—no one hurt, no one charged, but the nails lay around the street corner for weeks. Months later even, he leapt out of the car to find one rusty, bent nail for me to hold. There it is, the slow tick and prod of rusty violence. Indeed, the local papers still fill with the ugly trawl of retributive murders—not full-on warfare, but the numb tide of feuds between paramilitaries—this or that person shot in a parking lot; this or that person shot outside someone else’s christening; this or that person murdered for something that took place twenty years ago. For now, people also live together in the awareness that peace is a made thing, a culture one builds, and also a fragile castle a wrong tide can sweep away. As the poet Scott McKendry put it to me, “It’s apparent here in Belfast, but violence is always there just below the water table, and ignorance is a drill.” I’ve been pondering those words. After all, they seem quite apt for looking at America, too.

In the past few years, it’s been increasingly clear to all of us—in Belfast or beyond—that whatever realignments the nineties ushered in, history itself is far from over. So many walls are on their way back up. I arrived in Belfast in December 2016, six weeks after Trump’s election and a month before his inauguration. Yet even as I drank to this soft diplomacy of global friendship at my UK Fulbright orientation, rumors were already in place that Trump would dramatically shrink the State Department and oust longstanding ambassadors. Before long, we faced down the Muslim ban, and Robert Mueller began investigating Russian interference in our elections. The whole process makes it clear that not only have our US elections been deeply compromised, but also that the Cold War chill has (under the guise of sunshine) morphed into a new grim era whose landmarks and weapons we cannot yet fully know. Shortly after I arrived, the Northern Irish power-sharing agreement—fruit of that long-ago Good Friday—had been thrown into chaos by a wild corruption in the Democratic Unionist Party, a deeply fundamentalist Protestant party that (like our own deeply fundamentalist Protestants) opposes marriage equality and abortion rights, and is willing to hold the government hostage to get its way.

As the Brexit agreements get hashed and rehashed, Northern Ireland sits in the crosshairs. At stake is hardening the very border whose softening sped the peace along. People are eyeing passport regulations, getting married in case of immigration problems, looking for jobs in the Republic. Meanwhile, the past remains thorny. I had to travel a bit after my arrival, and on cab rides to and from the airport, I’d watch tangled trees looming over bare hedgerows. Protestant and Catholic cab drivers offered up radically different versions of the Troubles, and indeed of the entire history of Northern Ireland. The whole thing seemed impenetrable. Not only did history not seem over, it seemed never to have been settled in the first place.

These days, problems with Protestant and Catholic power sharing go on (Northern Ireland has had no functional government since January of 2017, or ever, depending on how you look at it), and this crisis is deeply intertwined with Brexit, which is itself a large-scale crisis about what citizenship means, what it means for anyone to belong to a country or a place, about what people believe they can or wish to belong to, about how to enforce or allow that idea of belonging. For the Northern Irish, who have been sitting at an unresolved colonial crossroads for nearly 1,000 years, this attempt to redefine hard borders on their island seems threatening. Yet even without the threat of violence, the idea of hardening the now-porous border between north and south is riddled with logistical nightmares. It’s an island, after all: Stability had allowed it some pleasant amnesia. At a forum on Brexit sponsored by the Fulbright Association, I learned that Bushmill’s crosses the border three times during its production. A recent brochure for tourism sponsored by Aer Lingus (based in the Republic) was more than happy to offer tours to the best of the Northern Irish tourist spots—and equally happy to profit from anyone wanting to visit them. Twenty-five years into the EU no one seems to remember who has fishing rights to which waters. The fish, of course, live beyond such concern.

Meanwhile, for people in Northern Ireland, some imaginary borders remain more potent than real ones. Protestants and Catholics harbor unsettled grievances: Each knows someone lost in brutality. Beyond this are traces of the high superciliousness of London: When I told a well-known London writer I was excited to be spending time in Belfast she sniffed and called it “scarred” and “backward,” insults that might not matter so much if they seemed to be hers alone. When the Northern Irish, well aware of the stakes, complain that Brexit agreements threaten them, they are caricatured in British papers as drunken louts. Walls may have fallen, but stereotypes haven’t budged a bit. A unified Ireland also seems a long way off: Some people feel it makes Protestants nervous about surrendering privilege and supremacy; others intimate that perhaps the more purely Catholic Republic of Ireland doesn’t really want this troublesome region back.

Exploring Belfast, I felt I might never decode it, never quite get to the bottom of its stories and counter-stories. Even so, block by block, mural by mural, people who live in Belfast do see the divisions and chart the healing over. Listening to accounts of bombings in Syria while in a cab, a taxi driver turned to me. “I hope to God we were never that bad,” he said, adding, “To be honest, I don’t know.” It is hard to know.

On a cold May day, McKendry, who is a Protestant and a poet and a trained electrician and feels that he was saved from engaging sectarian strife by having a Communist grandfather, took me on a tour of the council estates where he grew up. He was quick to let me know that I (an American visitor) received the same treatment as the migratory geese—I wouldn’t be hassled. A quick rain passed over. On the wide, rather bleak lawn, people were already gathering tires, old sofas, and pine branches to stack up for a long-off day in July when they would light an annual bonfire in honor of William of Orange, the Dutch Protestant Prince who defeated the English Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This date, however obscure it may seem to Americans, now serves as a Unionist mêlée in favor of the UK. The Union Jack flies on street after street in East Belfast, and the tire-fueled bonfires send up a sour stench and an ominous message to Catholics, even as the distant UK itself seems hardly to care a whit about the high passion of these far-flung patriots.

Passing an interface in the Peace Line, walking from the Protestant side to the Catholic one, I felt stuck in a kind of No-Man’s Land—for a moment less in the presence of peace and more in the realm of the brackish and stagnant. It reminded me of nothing so much as my father’s hometown of Danville, Virginia, where, once the mills closed, the people who had been brought there to work and the people who were there to threaten to break strikes were all left together, without jobs, with little to show except the ugly myths of supremacy and racism and divisions left festering between them. Like Danville, where people would rather have closed the libraries and public pools than integrate them, there are places in Belfast where the city has cut off its nose to spite its face, where the scars and stillness recall the enormous toll any place pays for cradling its hate. I say this because we in America are paying a huge toll, too, and it is high time we started to tally its cost.

Zadie Smith, whose husband, Nick Laird, is from Cookstown, in Mid Ulster, recently wrote that it does seem hard to understand how a minor doctrinal difference that’s at least five centuries old could cause so much pain. She’s right, of course—but the truth is, each place carries its pain, and the other question is how to heal it some rather than allowing it to fester or flare. Thinking of Northern Ireland, I often thought of a poem by Adrienne Rich: “There’s enormity in a hair / Enough to lead men not to share / Narrow confines of a sphere / But put an ocean or a fence / Between two opposite intents / A hair would span the difference.”

For all this grim history, there’s also something joyfully alive in Belfast—a kind of tenderness in this first generation, in this pink skin of a new life. I had never met so many young poets in one place living with such firm conviction in the life of art. Rather than imagining that history is or needs to be dead, these poets feel their place on the verge of a changing world, as well as their right to a deep past where poetry has persisted for centuries, despite all. The poetry magazine of Queens University Belfast for many years has been called the Yellow Nib, after a ninth-century poem, the oldest known to have come from Belfast. Here’s Ciaran Carson’s translation:

the little bird

that whistled shrill

from the nib of

its yellow billa note let go

o’er Belfast Lough—

a blackbird from

a yellow whinThat note, too, is their birthright.

When gathering poems for this portfolio, I didn’t ask any of these poets to write about of this, exactly. These poets know that their poems—maps born in language—are doing this work anyway, can’t help but do it as they bring us to recognize and breathe and hear and see.

A small note: In an era of blurry borders and multiple citizenships and migration, it is at times unclear what it means to be “of” a place. In this case, despite thinking globally, I really was pretty literal: I limited myself to poets who were born and grew up in Northern Ireland, with the exception of Conor Cleary, who is originally from County Kerry, in the Republic. While Northern Ireland is becoming more and more diverse, poets of the global diaspora have not yet really come of age in Northern Ireland. I expect they will, quite soon. Belfast, both because it has been violently unsettled and because it is not yet one of the bigger migratory hubs of Europe—these things being linked—has been relatively slower to become a center of global diversity, although this, too, is happening. While we lived there, our friends were from Egypt and Yemen and Saudi Arabia and Nigeria and Ghana. We were all migrants in time.

Back in the US, we weigh deep questions. How to write through and into our own troubles? What role does the poem play in politics, in the face of civic trouble, and of our fracturing? As we ask these questions with renewed urgency, I hope to offer American readers access to an emerging generation who have always shared these questions with them.

These Northern Irish poets have come up in the wary, generation-long gesture of climbing out from under a proverbial desk. They have always lived on the brink, on the edges of a quieted fault. In inheriting unsettledness, optimism, and the fragility of this peace, Northern Irish poets have quite a bit to offer the world right now. They know about weaving a society back together, and how quickly seams can unravel. Raised in a region once famous for linen mills, these poets also know that art is the warp and the weft of our common life, if we are going to have one. These poets know the capriciousness of borders, but also the lines of deliberate art.

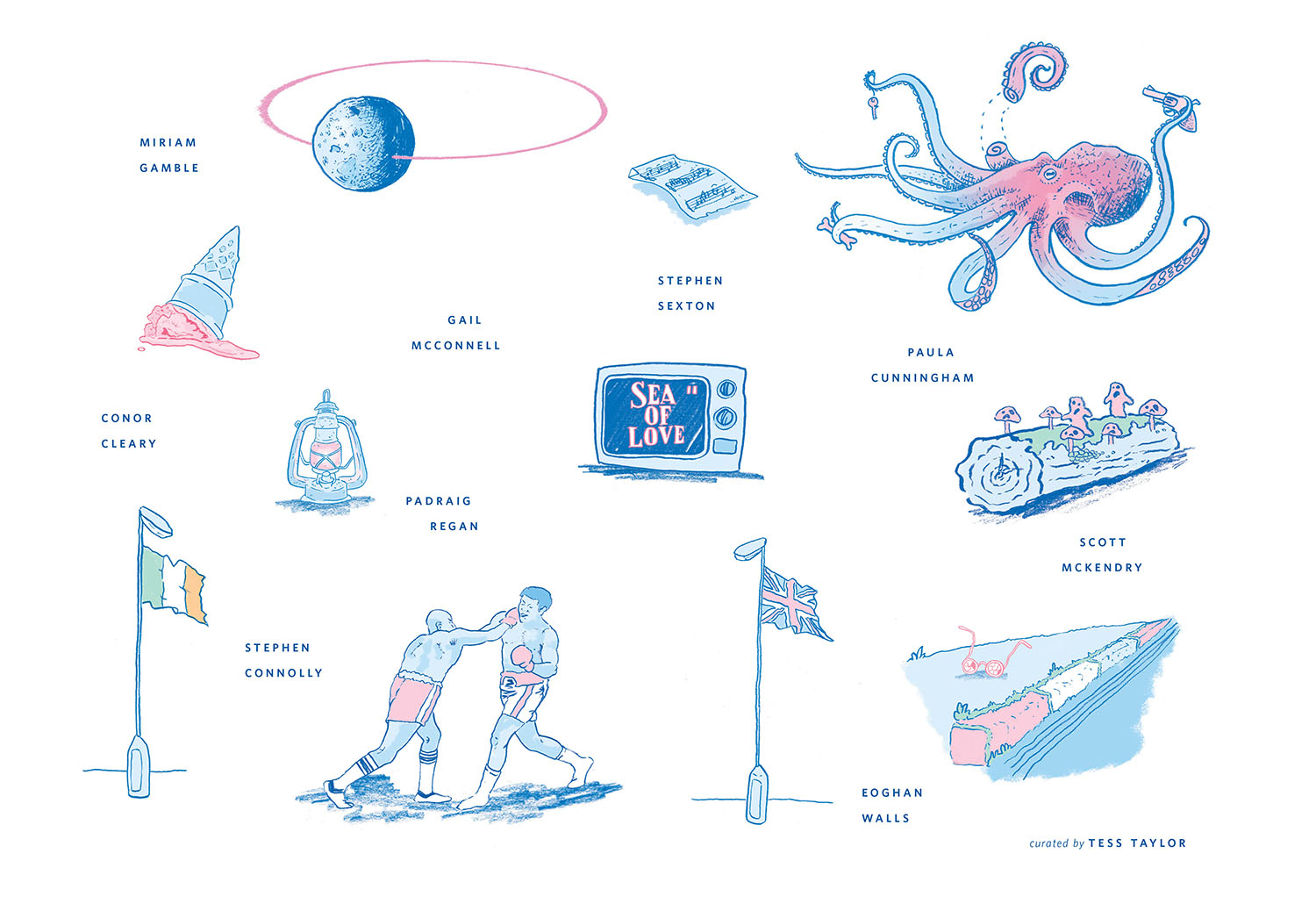

These poems remind us all to attend to our languages, our places, to the citizenships and histories that converge in them. They plumb the hyperlocal and look outward: In Scott McKendry’s dialect poems, geese, like American tourists, move with impunity through an otherwise supercharged space. His yarns capture a ritual neighborhood gathering piles of palates, tires, and old sofas (“a toxic stew of nasties”). In a scene that could be replayed in cities around the world (including the one near where I now write this essay), he offers sadly familiar portraits of surviving gang violence. Likewise, Stephen Connolly’s boxing poems jab between local and global, past and present, here and elsewhere, stringing the breath as hot wire between. Miriam Gamble’s elegiac “In the Annum”offers a sad parade of current apocalypses: Caught between destruction and revelation, one stops to admire the threnody. Paula Cunningham explores violence at once just out of the scrim of the poem and also at the center of its body, pondering how such “double-wonder” can be spoken. Conor Cleary’s “Transcription of a Keen”mourns the losses of the tribal voice set down in writing, and bears forward the question of how to find one’s voice now. As Stephen Sexton puts it elsewhere, “My mouth these many years was wealthy with pain.”

Pain perhaps, but also a wealth to say within it. Here we are these years later, our many borders about to be scrambled again. Here we are, as in Eoghan Wells’s poem, watching other bombs, other fracturing cities, perhaps with our own children trying to draw the world. Here we are, listening to hear what will happen. As we do, poetry helps us to sound our intimate selves, locate them against that big strange force, history. Poetry, as Padraig Reagan puts it, helps us “feel like a real boy, sometimes.” Here, as Gail McConnell says, we are so “startlingly set down.”