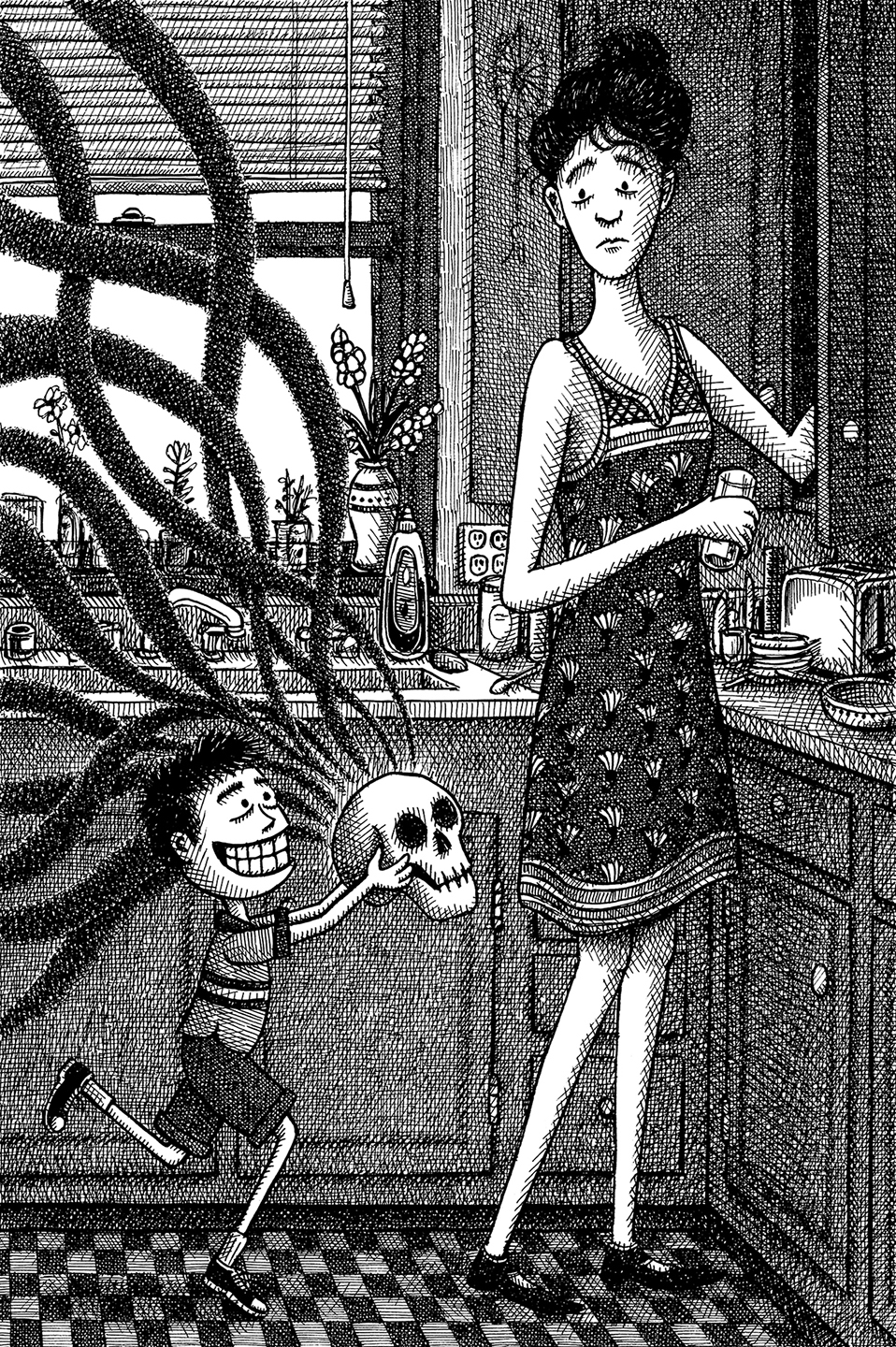

When your four-year-old begins talking incessantly about death, there are a few tactics for dealing with it. One is curiosity. Why do you want to die? Why do you hope you die today? Why do you love to die? Why do you want to kill yourself? The four-year-old doesn’t know what death is, not really, and so he cannot truly answer the question. But he feels a charge in the room when he speaks like this, no matter how much you try to stay cool and curious and turn a bizarre question into a teachable moment. “Mama, are you going to kill me today?” A toothy grin propping up his chubby cheeks, his eyes squinting in mirth. “No, I’m not,” I say with a wry smile, like, I see you messing with me, kid. It’s his new toy, the word “death.” Look at how it makes the adults get flustered! “Happy Death Day, Mama,” he says, the little creep. When my attempts to stay levelheaded fail, as they routinely do, the next tactic is to not take it too seriously. Treat it like one of those jokes he tells that always end with “diarrhea!!!!” Don’t think about my spouse’s brother, Aaron, dead at twenty-one; don’t think about my spouse, within earshot, undoubtedly thinking about him; don’t think about their mother and her unfathomable loss. “I hope I die today,” he says in a flippant chirp, as if he’s hoping we’ll bring him to Peekaboo Playland so he can wild out in a bounce house. “Die, die, die, die, die!”

“Where do you think he’s getting this?” my mother asks, her voice twisted with unease.

In a way, he’s always known about death. His first passion, as with just about any two-year-old, was animals, initially the livestock that populate just about every baby book—cows and pigs and chickens. His first attempts at communication came from the farm, snorting and grunting, mooing at us as we cooed at him. His love for animals felt so pure it broke my heart to feed them to him. “Hamburgers are cows,” I told him when he was eighteen months. “You don’t ever have to eat meat if you don’t want to.” But he did. There is innocence and there is hunger. Still, that time at Whole Foods, with him sitting in the cart, transfixed by the pinks, reds, and yellows of the butcher case…were they dead?

“Yes,” I told him.

“I want to go,” he said, and so we moved on to another aisle.

Later he got bored with domestic animals and went fully wild, glued to Disney’s The Lion Guard, the baby spin-off of The Lion King, where predators are sneaky and bad and the sleepy hordes of herbivores are good and protected by the guard (led, of course, by a lion). It stars a cheetah, too, but we never see her hunt. Horned animals became his new preoccupation: kudu, oryx, bongos, takin, yaks, markhor, bighorn sheep. In his animal play, the horned animals were the good guys, facing off against the carnivores, using their little plastic antlers to hook a deadly predator by the jaw and fling it across the room. I liked this identification with the underdog, the meek finding strength when they needed it most. Like every bit of animal-centric media geared toward toddlers, I ascribed a vividly anthropomorphic, even political, value system to all this stuff.

But play changes. Pretty soon he became enamored of the carnivores: Komodo dragons, with their poisonous drool; scorpions with their pincers and stingers; all sorts of sharks. Around age four, his viewing shifted from shows like The Lion Guard to documentaries like Planet Earth II. There’s a scene in the latter film that, to him, is pretty much the best thing ever, where marine iguanas, just hatched and crawling out of the pebbly sand, sprint for their lives toward the cliffs that buffer the ocean, pursued by an impossible number of racer snakes, a plague of them, long and rubbery as toys brought to life by something evil. How do any of the lizards survive, alive for less than a minute and with death already on their tail? My son roots for the iguanas, of course, but he also loves the snakes, their slick speed, their bizarre muscularity as they raise themselves up and strike at the babies. My son does not identify as a baby.

“He knows animals die,” I tell my mother. He knows they die to become our food. He knows they kill one another for sustenance. He knows about extinction, the dinosaurs, a motif of childhood: A whole world was here and suddenly was gone. He knows that animals are endangered. He knows whole species die off.

Creaturepedia: Welcome to the Greatest Show on Earth, by Adrienne Barman, is a bright and goofy book of illustrated beasts grouped into whimsical categories, one of which is Endangered. These imperiled beasts are depicted not in their habitats, as elsewhere in the book, but as portraits, each animal’s visage framed, its eyes brimming with blue tears. The drill looks comically traumatized; the Ethiopian wolf’s eyes bug with sorrow; the golden lion tamarin seems totally freaked out. For a while, this was my son’s favorite chapter. I saw the opening: I explained habitat loss, and when he was gifted with a toy logging truck, it was hard not to see it as propaganda and connect the dots for him. “Trees being cut down is a big reason why animals become endangered,” I explained. And so a new game was created, one where the logging truck was utilized to transport animals from their devastated habitats to newly fashioned replacement habitats, the orca and Arctic wolf and penguins gathering in a new Arctic, the toucan in a new rain forest, and so on. I shouted out to my spouse—whom my son calls Baba, a word increasingly used by gender-nonconforming parents on the masculine spectrum—“Baba, we’re playing environmental apocalypse!” Their laughter, cynical and appreciative, echoed through the house as we rehomed the animals, region by region.

It didn’t take long for the endangered animals to be eclipsed by the fierce and the poisonous. At one point, scrutinizing our viewing habits, Netflix’s algorithm brought 72 Dangerous Animals: Asia onto our home page, and my son watched it, followed by 72 Dangerous Animals: Latin America, Australia, and North America. That death is wound tightly into life, into the very ingenious structures of so many animal bodies, is clear. I try to explain evolution, though the span of time is hard for even me to get my head around—change occurring over millions of years so that we may live so very briefly. My son ignores me, much more interested in the sinewy capacity of a reticulated python to constrict the life from the lungs of an adult human. And I can’t blame him—the show is fascinating. We become enraptured by the survival story of a swimmer who’d become ensnared in toxic ribbons of a box jellyfish, nearly dying. By the show’s end my son’s mind, stunning in its capacity for hoarding facts, brims with new statistics about crocodiles, needlefish, and water buffalo.

Then, Bif died—our beloved cockatiel. When he was thirty, I spent an entire Thanksgiving holiday investigating how to enter him into Guinness World Records. Amazingly, he wasn’t the oldest cockatiel in the game—these birds possess a startling longevity, and it’s entirely possible that Bif would still be alive if my spouse and her mother had not brought the bird in to be euthanized. Seeming to have suffered a stroke, one wing hung oddly, and he would fall from his perch, linger on the floor of his cage in the poop and seeds. His small eyes were cloudy and blind. There was concern that his quality of life was low, though this is hard to detect in a pet bird, their quality of life being already so curtailed, what with the cage and all. In his heyday, Bif had the run of the house: shitting all over the banister, hanging out on top of the fridge, landing on the kitchen table to join the family for a spaghetti dinner, slurping up a noodle, marinara on his feathers. The bird had belonged to Aaron and had slept in the bed with him as a cat or a dog would. Now Bif’s sole outings were trips to the bathroom for my spouse to place him, blind, in the shallow water of the sink, cupping it and dripping it over his feathers. Bif lived in the cage beside our bed, his fluttering a constant, soft sound. And then he was gone.

“Bif is dead. Baba is sad,” my son told me.

“Yes,” I nodded. “Baba is sad. They love Bif.”

“I’m not sad,” he said, almost bragging, happy to be spared bad feelings. When my niece’s hamster died, she didn’t shed a tear either, nor did my nephew when Jelly the Fish went belly-up in his bowl atop the dishwasher. Children are feral, self-obsessed, short on empathy, uncomprehending of this ultimate loss. Also, they’ve spent less time on Earth being brainwashed by the illusion of time. Like the mystic and the physicist, they seem to grasp that it’s all a dream. And if time isn’t fully real, neither is death.

As he continues waxing on death, my son becomes enchanted by infinity. “Numbers are infinity,” he says, testing his understanding on me. “And space is infinity.”

“Yes!” I say, thrilled.

“And death is infinity,” he finishes. Does this mean that he is beginning to understand the infinite nothingness of death? I’m stumped by the truth in his observation, and the knowledge that unlike numbers and the universe, which expand ever outward, death is a stoppage. At least, I think it is.

We spoke about my son’s infatuation with death at our preschool, a co-op that runs on the premise of nonviolent communication, a method of parenting that relies on keeping your cool, asking questions, meeting the children where they are, even if, as recounted by the nonviolent-communication workshop facilitator, where they are is melting down on the carpeted floor or at the local multiplex. You get down there with them, stares and judgment of the passersby be damned. This methodology respects the development of the human brain, taking into consideration that a child’s brain is, in the words of one workshop facilitator, “on fire.” In nonviolent communication, compassion is pretty much your only tool. You love your kid through whatever freak-out they’re having, biting back your shouts and screams and threats and all other unhelpful expressions.

A parent who has taken three children through this school recommended a book called Lifetimes: The beautiful way to explain death to children, by Bryan Mellonie and Robert Ingpen. Its self-congratulatory title didn’t inspire much hope, nor did its cover illustration of a fallen oak leaf floating on a pond. My son’s ability to detect a book’s didactic agenda, and his intolerance for such literature, is proportionate and strong. Every social-justice book I’ve ever brought to him—A is for Activist, Feminist Baby, icon bell hooks’s energetic Be Boy Buzz, biographies of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Yayoi Kusama, Mary Blair, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg—has provoked tantrums at the flash of a cover. He’s only interested in animals or the occasional anthropomorphic automobile. He can sense when I’m trying to teach him something, and he hates it. “Well, I want to read it,” I said, loading Lifetimes into the bedtime book pile. The look of its sentimental autumnal scene, the terrible font—it set him off. Still, I insisted we give it a try.

“There is a beginning and an ending for everything that is alive,” I read to him (using my “reading voice,” gentle and prim, imposing an extra-twee vibe on the material). “In between is living.” The text, simple and blunt, edges toward a sort of poetry. But the illustration of a nest, straw whirling around speckled blue eggs, did not impress. Perhaps if an eagle were perched there, cracking into the fragile shell with its beak, maybe that would have grabbed him. “All around us, everywhere, beginnings and endings are going on all the time.” A murky watercolor of time-worn seashells arranged in a circle. My son wasn’t having it. “Look, there are animals in it!” I tried, flipping past illustrations of fruit and gnarled tree trunks to a picture of a dead bug on its back. No. None of it worked. I let the book slip to the floor and we moved on to his latest favorite, Poop: A Natural History of the Unmentionable, by Nicola Davies and Neal Layton, whose fascinating information (bunnies eat their poop to get enough nutrients!) is presented within a brown and smeary aesthetic.

“Mama, who is the youngest person you know that died?” He was in the tub, moving around fluffy islands of bubbles. I was sitting on a stool, spacing out.

“The youngest?”

He nodded. Having never known Aaron, it was either Alexis or Laura. Alexis, who had gone to the doctor repeatedly for stomach issues, turned away again and again with a shrug until a desperate emergency-room visit revealed colon cancer. Laura, who came home alone from a party and ingested some sort of drug in her bedroom—heroin or a pill, I could never bring myself to ask, don’t know if it matters. Who was younger?

“Thirty-five,” I say, a guess.

He brightened. “That’s old!”

“Yes, that is old. But usually people die much, much older than that.”

He returned his focus to the bubbles, the soft, crackling noise of them melting and popping beneath his wet hands. I let the sadness of Alexis and Laura linger. Alexis, whom I never really spoke to as she was dying because we’d fallen out of touch, and it felt too awkward (like, Hey, I hear you’re dying; thought I’d reach out); and Laura, to whom I’d given her first opiate (even though I’d protested, and my boyfriend had said, She’s an adult! and Laura herself had said, If you don’t give me some I’ll just ask Ricky, and we all knew Ricky would have done it, and so I passed her the straw and the spoon full of murk, warning her, “Just don’t OD and make it my fault,” and though it took more than a decade, that’s basically what happened).

I would love to talk to my son all day about death so that I could know what it means to him, this disturbing talk. It could have some meaning and direction and not just be a morbid existential scab he’s picking at. Once, climbing up the inflatable stairs of a blow-up water slide, he told me that when he turns seventeen years old he will be grown enough to simply leap from the top into the shallow pool below. “If I don’t die before then,” he added. My head snapped up. I was seated on a patch of shaded grass. We were at a classmate’s house in Pasadena, after school. The sun in the sky blared. “You won’t die before then,” I said, springing up from the lawn, walking toward him swiftly as if he were suddenly in danger.

“How do you know?”

“Most people do not die before they’re seventeen, and you won’t either.” Following a fact with a wish so desperate it can’t even be acknowledged as a wish.

After the failure of Lifetimes, I brought home a new version of Margaret Wise Brown’s The Dead Bird, with pictures by Christian Robinson, one of my favorite kids’-book illustrators. Robinson’s Last Stop on Market Street, written by Matt de la Peña, and noteworthy as a children’s book that deals with class, was rejected by my son: no animals, and a palpable social-justice message. Two strikes. Robinson’s Leo: A Ghost Story (written by Mac Barnett) fared somewhat better, since all things Halloween are cherished by my son; he also cracks up at slapstick depictions of fear.

The Dead Bird had a lot going for it—for starters, the word “dead” right there in its title. And perhaps my son’s relationship to his own dead bird helped it resonate with him on a deeper level. There was, too, the bright grass on its cover, the feet of children flanking the dark silhouette of one very dead bird. He was down.

In The Dead Bird, a multiracial quartet of children who appear too young to be roaming an urban park alone are doing just that, toting kites and wearing fairy wings and fox costumes. Accompanied by a large and leash-less dog, they find a dead bird in the grass. Even as they hold it, it begins to get cold, and the body begins to stiffen. Of course, the children must be chaperone-free in order to get so hands-on with this newly dead creature. (On a recent preschool camping trip, the children had discovered a dead lizard, its skin beaded as an antique purse. All of us parents forbade them repeatedly from touching it.)

With no adults around, the four children—with the improbable help of the dog, which in real life would likely have eaten it, or at least rolled around on it—take on the mature work of handling the dead creature. They have a funeral and sing to it the way grown-up people do when someone dies. The hymn is childlike and frank: “Oh bird you’re dead / You’ll never fly again.” The solemnity of their singing, the scent of the ferns, the very fact of the bird’s death: Something about this tableaux penetrates their youthful narcissism and engages it. The tombstone they make for it reads: “Here lies a bird that is dead.” The children tend the grave every day, until eventually they forget to.

Brown’s ability to authentically capture death as processed by young children is proven, I think, by my son’s interest in the book. Though the kids play at the sentimentality they may have witnessed among grown-ups, it doesn’t quite fit them. There are no deep thoughts, just the blunt understanding of there being no more and the curiosity of the bird’s body, a wild animal they are, thanks to death, allowed to observe closely, even handle. My son would have loved to hold that limp green lizard they’d found on our camping trip, its jeweled scales. Away from the suffocating fretting of so many parents, who knows what strange ritual the kids would have created? A vivisection with a stick? A ceremonial toss into the brush? A burial? In the end, the lizard was left to rot in the shade of a large stone, and as a light-up Frisbee took to the air amid some flapping bats, the little reptile was forgotten.

Nonviolent communication be damned, I have snapped at my son when he gets deep into his death chatter, on nights when I am more tired and less patient, when my annoyance at the monotony of his shock talk clashes with other prickly and creeped-out feelings. Or, when it reminds me of Aaron, who died alone in a room doing something stupid, breaking everyone’s hearts forever. One such night, my son was in the bath. The end of the day finds him tired, and when he is tired he gets goofy and is more likely to engage in his unsettling death songs.

“Stop it,” I ordered him, my voice harsh. “Do you understand what happens when you die? You never, ever, ever come back, not ever. You are gone forever. Do you understand that?” The intensity in my voice surprised me, and provoked a flicker in his eyes. Instantly I felt bad—because of course he doesn’t understand, and is this how I want to introduce the concept, hissing at him at the end of the day, his faculties frayed? What if I’d been successful and he finally comprehended with some kind of awful clarity the unfathomable permanence of death, the nauseating brevity of our lives? The eventual and profound loss of me, his mother—not to mention his Baba, his nanas, his aunts and uncle and cousins? Do I really want him to have an existential crisis, his first, at age four in a bathtub on a Wednesday night at 6:30?

Well, he didn’t. He doubled down with defiance, as is his way. People have told me that four is a glimpse at fourteen, and truly I was chilled.

“That’s good, I like that, I like death.”

“Okay fine. Like death, then.”

I drained the tub and crushed the bubbles lingering on his skin with a towel.

Anastasia Higginbotham’s Death Is Stupid is part of her Ordinary Terrible Things series, which breaks down sucky or confusing aspects of life—divorce, whiteness, sex—for kids. Death Is Stupid is illustrated in collage and paper cut-outs sophisticated enough to work but rough enough to inspire an artistic impulse in a young person, with deconstructed paper-bag backgrounds and text handwritten in black marker.

“Death isn’t stupid,” my son predictably proclaimed. “I love death.”

“Yeah, I know. But you’ve only seen death on television shows. Some people have someone they love, someone really important to them, die, and they don’t love death. Death took their mom away, or their dad or Baba or Nana.”

In Death Is Stupid, a kid processes the death of his grandmother, all the while batting away the platitudes that a well-meaning but checked-out grown-up can lay on a little one, assuming that because he believes in Santa Claus it means he’ll believe that his loved one is “sleeping” or has gone to “a better place.” The book respects the fact that a child’s propensity for magical thinking coexists with a pretty strong bullshit meter. It shows the child in grief, and in anger, annoyed at adult failure to help him process major loss, and it provides simple crafts and rituals that encourage kids to figure out how to honor the trauma in a manner that feels authentic.

When I asked my son if he liked the book, he said no, but he also said he didn’t like An A to Z of Monsters and Magical Beings, by Rob Hodgson and Aidan Onn, even though he went wild over the discovery of the snake-headed Questing Beast; or Lemony Snicket and Rilla Alexander’s Swarm of Bees, in which an angry child hurls tomatoes at people and places all over town, including a hive of pissed-off bees, even though he requested it at bedtime. Unsurprisingly, my son adores stories of children misbehaving; Jim Whalley and Stephen Collins’s Baby’s First Bank Heist, in which a baby robs a bank and fills the house with exotic animals while his mom is distracted on her phone (too real!) is another favorite/not favorite.

When my son professes to dislike books I bring him, books I’m excited about, he’s individuating. He’s not me. He’s himself. And I know him a little less for not understanding that of course he wouldn’t like Swarm of Bees, and to know him less means to possess him less, it means he belongs to himself, and can figure out who that self even is. I get it. But he’s four. It feels way too soon for this shit. Kids are so smart, their psychology so developed and so complicated, too quickly. He’s this miniature teenager, proudly loving death and badness and everything I don’t like, telling me that when I die he’s going to become a bad guy, because I won’t be around to stop him. Like anyone, he wants freedom. But he ends every day cuddled in between me and my partner, hugging his tattered blankie close to his chest, promising me that he’s not going to sleep in his own bed until he’s at least eleven years old. And I’m all for it.

I can approach my son’s death obsession with openness, posing questions he is unlikely to answer. I can sternly tell him to stop, watching him delight in his competency at upsetting me. I can make light of it, which is what I usually do, ignore it or not take it seriously. This does not stop it so much as it preserves my mood and prevents it from sliding into gloom or irritation.

I can also embrace it. If four is in fact a glimpse at fourteen, a reflection on my own self at fourteen is perhaps illuminating. I coated my face in white grease paint just to look like a ghoul. My eyes were lined like an Egyptian sarcophagus; my lips painted with black lipstick year round. My mother was horrified. We fought terribly. She was disgusted by the video for Skinny Puppy’s “Dig It,” in which they appeared as sexy vampires digging their own grave, a video I had recorded on VHS and watched on a loop, hormonal, dreaming of my own vampire boyfriend. People on the streets of 1980s Boston spit at and hit me. When I shared this with my family, hoping for outrage and sympathy, I was ordered to stop being a weirdo and bringing such punishment on myself.

“You’re goth,” I told my son the other day. “Do you know what a goth is? They wear black clothes and they love death. They love skeletons and skulls and all Halloween things. They love spiders and spider webs and bats and scorpions.” His eyes gleamed and his smile ate up his face as I enumerated all the things he most loves. “They listen to a kind of punk music,” I continued. “They love The Nightmare Before Christmas. They love vampires.” (To date, the only answer I have gotten from my son, when asking him why he wants to die, is so that he can become a vampire. This is, I believe, a fair answer, and I told him as much.)

Sometimes my son kills me while we’re playing. I have an uneasy rule against toy guns, inspired by my sister, who has proudly told her children that theirs is “a no-gun house.” When my spouse brought home a 1950s-inspired toy laser gun, I freaked. I said no, and tried to explain in age-appropriate language that real guns are a big problem in our world, and we as a family want to stop that problem and so we do not allow pretend guns in the house. But truly, the explanation felt weak, and still does, and hard to enforce as so many of his super-villain figurines come packing heat. My son will pick up anything and imaginatively use it as some kind of shooter. What he shoots are not bullets but poison, electricity, and green oil. The green oil has the power to change good guys to bad guys, superheroes being his latest preoccupation. He shoots me often, and I die. But soon I’m reanimated by his touch and the word “better,” and I rise, no longer dead, ready to rejoin the play.