BACHELOR JOURNEY

In July 1908, a twenty-five-year-old Franz Kafka quit his post at the Assicurazioni Generali with a medical note claiming he was suffering from “nervousness” and something potentially complicated having to do with his heart. This despite passing the medical examination when hired less than a year before (height: 5’11”; weight: 134 lbs.; nutritional status: “moderately weak,” digestion and appetite surprisingly normal; an “even,” “buttery yellow” urine stream). Now a trainee at the Workers Accident Insurance Institute, he had a certain amount of vacation every year (two weeks, taken in late summer or early fall, which he stretched to three with a medical note about his nervous exhaustion). He was lucky—a six-hour position, no second shift. For a Jew to find, no less. He began the first of his holidays with the Brod brothers, Max and Otto, in northern Italy (the airshow at Brescia, the waters at Riva). The next trip they took was to Paris, in the fall of 1910. The plan was to stay for three weeks, though he would only last for one.

THE SPECIFIC NATURE OF HIS MISERY

The earliest extant Kafka diaries we have are from this period, when he used his time off to travel for pleasure. Now that he had time, he could write—or, really, complain in writing about not having enough time to write. This is when the young Kafka begins to philosophize his writer’s block. Many of these entries are from Sundays, when he had to contend with the chaotic domestic atmosphere of the Kafka household. There is a compressed anxiety to these entries. Reading the early diaries, it’s clear that Kafka felt incapable of writing the kind of sentence he desired. “I write this very decidedly out of despair over my body and over a future with this body,” he writes on one of the first pages, a manifesto that catalyzes his practice.

FLAUBERT OR PORTRAIT

Before that first trip to Paris, Kafka and the Brod brothers studied French, mainly to read Flaubert’s Sentimental Education in its original language. There was little Kafka loved as much as that book. Max Brod soon declared Sentimental Education his favorite book as well, hanging a portrait of Flaubert over his desk. Kafka saw himself as the spiritual son of Flaubert. Like Kafka, Flaubert lived and worked in his familial home. In 1842, Flaubert was a failure as a law student, a mess of nerves and migraines, miserable in Paris, habituating brothels instead of lectures. All this Flaubert channeled into his character Frédéric, the bored and voluptuous law student. I envision Flaubert’s dandy Frédéric (in pressed coat and patent-leather boots) next to that image of Kafka as a young law student himself, a photograph made sometime in 1906 and often reproduced in biographies—English bowler, frock coat, stiff collar. A stiffness or stillness to Kafka’s gaze here, like so many photographs from the turn of the twentieth century. He is holding a look, somewhat awkwardly, most likely at the photographer’s insistence. Biographers often interpret this gaze as a melancholy one, reading into it his later tales of alienation. There’s a mystery to this photograph of Kafka before he became Kafka. It is difficult to know what he is thinking here. I don’t think he looks melancholy. If anything, there’s a wryness to his expression, although it’s rather blank. What did Kafka see? What is behind his gaze? This is what I’m searching for.

Before that first trip to Paris, Kafka and the Brod brothers studied French, mainly to read Flaubert’s Sentimental Education in its original language. There was little Kafka loved as much as that book. Max Brod soon declared Sentimental Education his favorite book as well, hanging a portrait of Flaubert over his desk. Kafka saw himself as the spiritual son of Flaubert. Like Kafka, Flaubert lived and worked in his familial home. In 1842, Flaubert was a failure as a law student, a mess of nerves and migraines, miserable in Paris, habituating brothels instead of lectures. All this Flaubert channeled into his character Frédéric, the bored and voluptuous law student. I envision Flaubert’s dandy Frédéric (in pressed coat and patent-leather boots) next to that image of Kafka as a young law student himself, a photograph made sometime in 1906 and often reproduced in biographies—English bowler, frock coat, stiff collar. A stiffness or stillness to Kafka’s gaze here, like so many photographs from the turn of the twentieth century. He is holding a look, somewhat awkwardly, most likely at the photographer’s insistence. Biographers often interpret this gaze as a melancholy one, reading into it his later tales of alienation. There’s a mystery to this photograph of Kafka before he became Kafka. It is difficult to know what he is thinking here. I don’t think he looks melancholy. If anything, there’s a wryness to his expression, although it’s rather blank. What did Kafka see? What is behind his gaze? This is what I’m searching for.

TOURIST

The first time he was in Paris, Kafka did not keep a travel diary. The three young men on holiday most likely behaved as typical male tourists: They went to the postcard sites, to the cabarets, to the night cafés, to the theater, the Louvre. Kafka went alone to the horse races. There were no specific traces of Flaubert’s haunts to follow. Perhaps they would have wished to find Monsieur Arnoux’s art shop on the boulevard Montmartre, but it would not have been there.

TRAFFIC

In his unfinished story “Wedding Preparations in the Country,” Kafka attempted to copy the spirit of the early passage on Parisian traffic in Sentimental Education, a paragraph that must have resonated with him as he first encountered the streets of Paris. The paragraph itself is a form of traffic. At first the phrases and sentences circulate like the women lolling in their barouches, the flow and swarm of bodies and vehicles in the city, the sentences gaining movement and momentum. While Frédéric takes in the scene, more and more carriages appear, rubbing against each other, mane against mane, lamp against lamp, while he imagines the face of his beloved Madame Arnoux appearing in one of the broughams. Everything is bottlenecked and cramped, until a scattering of the carriages that is like a sexual release. The traffic disperses as the sun goes down, the gas lamps burning.

BOILS

Kafka’s Paris was louder and faster, dirtier and more clogged than Flaubert’s. Kafka was fascinated and horrified by the noise of the Métro. He arrived in Paris with a sprained toe and a breakout of furunculosis—pus-filled bumps—all over his back. He kept on having to wrap his torso tightly so as to cover the wounds. As he roamed endlessly through Montmartre, up the grand boulevards, the bandages would loosen, and he would give up and return to his hotel. After a week of constant pain and itching, he decided to go home to Prague and tend to his malady. In three postcards to the brothers Brod sent to their hotel in Paris (a reversal of a postcard’s purpose), he performs a quippy hysteria. “Dear Max, I arrived safely and only because I am regarded as an improbable phenomenon by everyone I am very pale. —The pleasure of shouting at the doctor was denied to me by a little fainting spell, which forced me onto his couch and during which—it was peculiar—I felt myself so very much a girl that I attempted to put my girl’s skirt in order with my fingers. For the rest, the doctor declared that he was horrified by my appearance from the rear, the 5 new abscesses are no longer so important since a skin eruption has appeared that is worse than all abscesses, requires a long time to heal, and produces and will produce the actual pain.” He confesses in the next postcard that he suspects this more recent eruption was the eruption of the city of Paris onto his body, its sidewalks running through him, his body a bumpy, inflamed map. At home in Prague, he must sit still in his plaster cast, which is unbearable, and he dreams at night of Paris traffic.

DREAM

In the third postcard, he writes of a dream of sleeping in a large house populated by such traffic. How sleep hung around his dream like scaffolding around a Parisian building. “I had been lodged for sleeping in a large house that consisted of nothing except Paris horse cabs, automobiles, omnibuses, etc. which had nothing better to do than drive close beside each other, past each other, over each other, and under each other and there was no talk or thought of anything but bus fares, connections, transfers, tips, direction Pereire, counterfeit currency, etc.” Reading this last unwinding passage, I am reminded of the snapshots of dread and anxiety in Rainer Maria Rilke’s Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, which was published sometime in 1910. Kafka could easily have picked up his fellow Prague writer’s novel of fragments in a Paris bookshop; perhaps he even read it on the train home, and this somehow infected his prose, which after this first Paris trip begins to grow denser and more complicated as he attempts to document what he witnesses, much like how Rilke’s Malte meditates upon the shock and nervous energy of Paris in 1902. There’s a striking parallel between both Kafka’s Paris writing and the opening of Rilke’s work, with Malte kept awake in his bed by noise and shadows, navigating a sleepless night: “To think that I cannot give up sleeping with the window open. Electric street-cars rage ringing through my room. Automobiles run their way over me. A door slams.” Then again, this could simply be a form of sympathetic plagiarism, a twinning of how this city infects the writer and their literature.

A SECOND LIFE

Although Kafka didn’t keep a diary on that first trip to Paris, the experience leaches into his later notes, and over time he romanticizes this disastrous failure of a trip. He knows he’ll return. On February 21, 1911, he writes, “My life here is just as if I were quite certain of a second life, in the same way, for example, I got over the pain of my unsuccessful visit to Paris with the thought that I would try to go there again very soon. With this, the sight of the sharply divided light and shadows on the pavement of the street.” Toward the end of 1910, upon returning from this trip, Kafka begins to inhabit his diary regularly. He returns to the imagery of Paris traffic as a metaphor for writer’s block. When he sits down at his desk, he feels “no better than someone who falls and breaks both legs in the middle of the traffic of the Place de l’Opéra” with carriages rushing “from all directions in all directions.” And yet, “that man’s pain keeps better order than the police, it closes his eyes and empties the Place and the streets without the carriages having to turn about. The great commotion hurts him, for he is really an obstruction to traffic, but the emptiness is no less sad, for it unshackles his real pain.” The emptiness here is the emptiness of the blank page. In these entries there is also a renewed commitment to writing, a desire to devote all of his available energies to the act of literature, which includes his diary, a form of documentation and punctuation as to whether he was able to write that day. At ten o’clock at night on November 10, he writes that he will not let himself be tired, he will “jump into my story even though it should cut my face to pieces.” The nocturnal rhythm of writing becomes a second shift of the day, when he refuses sleep in order to write.

AVIARY

During the day his room was the center of the entire Kafka apartment at Niklasstrasse 36, fourth floor, where he lived with his parents, his three sisters, and a maid. Since he was situated between his parents’ bedroom and the main living area, in the morning he was routinely subject to whispering, yawning, the creaking bed of his parents, doors slamming, his father bursting through, robe trailing, the boom of his voice, has my hat been cleaned yet? In a piece titled “Great Noise,” Kafka describes this typical Sunday family disorder, his attempts to work, his slithering like a snake into the living room to beg his sisters and their governess to please be quiet. Kafka had his own room, unlike his three sisters who crowded into one, yet biographers still sympathetically note how cold and cramped it was. Kafka was mordantly sensitive to noise. As accompaniment to everything else, there was the constant chirping of the canaries. At night in the Kafka household, once everyone else was asleep, Kafka would go into the living room, place a cover over the cage, a blanket on his lap, and continue filling up another of his notebooks. This was the domestic sphere that Kafka was trying to escape through his bachelor journeys. He worked at home, and his work was of the home, the enclosed and often claustrophobic domestic space. Traveling was a way to disappear, and also to escape his family, especially his father.

FATHER

In K., his book on Kafka, Roberto Calasso writes of the transformation of photographs of the patriarch Hermann Kafka, before and after his son’s death at forty from tuberculosis. In earlier photographs, Hermann, the son of a butcher, looks like a boxer—a robust man with a thick neck and twirly mustache—even though he is dressed dapperly in a formal suit and bow tie, as befitting the owner of a wholesale fancy-goods store. It is easy to imagine him brutalizing his son with his sheer presence, sucking all the energy out of a room. In a photograph of Kafka’s parents after their son’s early death, Hermann, wearing a three-piece suit, now looks much older. He has shrunk to half his former size. The son in his lifetime shrinking before his father’s oppressiveness, and then afterward, the father becoming more anemic and frail, mirroring his son after death. Kafka the son is often thought of as the sickly one, but his father dramatized his health as well. You weren’t supposed to excite him because of his heart condition, and like the rest of the family, he vacationed separately at various sanatoriums. In 1911, the night before he was to leave with Max Brod on their trip through the continent, Kafka recorded in his diary that his father was quite ill—suffering from insomnia because of anxiety over his business, which had exacerbated his illness. Up all night vomiting. Pacing back and forth with a wet cloth on his heart, loudly sighing.

TRAVEL DIARY

They departed Prague by rail at noon on August 28, 1911. Onward to Italy through Switzerland. The plan was for the two friends to individually keep travel diaries and later collaborate on turning their notes into a satirical travelogue they would title Richard and Samuel: A Brief Journey through Central European Regions. The idea behind these travel diaries—to describe not only the trip but also their feelings toward each other along the way—was, Kafka writes (rather punchily), “a poor one.” Later, over the months they met at Brod’s house on Sundays to work on this book, Kafka became so frustrated that he wondered in his diary whether he should keep yet another private notebook, one he would not share with Brod, devoted to complaints about this project and their friendship. The opening of this travel diary chronicles in some detail the first leg of the trip, on their way to Munich. Later the two would fictionalize their encounter with a young woman, Alice R, with whom they flirt on the train, and then later share a quick and giggling evening taxicab through Munich, in the first and only chapter of Richard and Samuel, titled “The First Long Train Journey Prague–Zurich.” It’s telling how quickly Kafka wrote the first passage in his travel diary (probably worked on it over a day), and then how many months it took to turn it into something else, how torturous this process felt. How slow it can be, any attempt to make fiction out of the present. It is clear reading both his present-tense travel diaries and his more layered memories written at the end of the trip that Kafka viewed his vacation as a writing holiday, for paying attention and taking notes. While at a table outside of the cathedral in Milan, he writes that it is “inexcusable to travel—or even live—without taking notes. The deathly feeling of the monotonous passing of the days is made impossible.”

TRAIN

The notes he takes from the train are dashed-off, hyphenated bursts, like the stop and start of passing through stations. Later, in the reading room at the sanatorium in Zurich, going through his notes, he meditates that there is a calmer, more pastoral mode of thought in Goethe’s travel diaries because of the slowness of the horse-drawn mail coach. The aphoristic quality of Kafka’s travel diary. On his way to Paris, he writes, “I didn’t know whether I was sleepy or not, and the question bothered me all morning on the train. Don’t mistake the nursemaids for French governesses of German children.” When Brod remembered their abbreviated stay in Milan, a city he detested, he thought of a train model he saw there in a toy store window. A model also for their collaboration—circling around and around, going nowhere.

SWIMMING

Look closely at the picture postcards Kafka sent home to his sisters Ottla and Valli, at the vast blue of the lakes surrounded by mountains, and you can see the two friends of differing heights bobbing gently in the water. Such an awful, abnormal heat wave, the summer of 1911. They embraced with relief in the water at Lake Maggiore in Stresa. The two of them believed they must swim in a body of water to establish a physical connection with, and thus possession of, a landscape. Before his trip, Kafka records that although he has failed to write a word all summer, he has spent much time swimming, mostly at the Civilian Swimming Pool in Prague, and in doing so conquered something of his despair and disgust over his frailty. Finally, he stopped being ashamed of his body in the swimming pools in Prague, Königssaal, and Czernowitz.

CONSTIPATION

His worry over his poor digestion and his health or relative fitness was a labor he undertook during the day that almost matched the ardency of his nighttime literary investigations. The attempt to relieve his constipation marks a rhythm in the diaries. Having just returned from his three weeks traveling, he records that a friend recommended a more natural laxative, a powdered seaweed that swells up the bowels. Kafka loved to list food, as in a letter to Max Brod from the Swiss sanatorium in the final, solo, doctor-prescribed leg of his trip. Rather than draft the story Brod instructed him to work on, he writes about his sluggish digestion and lists his meals: mashed potatoes, applesauce, vegetable and fruit juices, whole-grain breads, omelets, puddings, and above all nuts. His biographer Reiner Stach notes Hermann’s irritation at his only son’s daily breakfast (yogurt, chestnuts, dates, figs, grapes, almonds, raisons, berries, whole-grain bread, and oranges). Kafka’s travel diaries are often punctuated by what he ate. The butter served at breakfast at the temperance restaurant in Zurich “like egg yolk.” In Lucerne: pea soup with sago, baked potato, beans, lemon crème. At a café at twilight in Paris: “I ordered a yogurt, then another.”

FRUIT

“Fruit,” he notes in Switzerland. In Zurich Kafka is happy to be out of his room, though he would have liked to have had some fruit. In Italy suddenly: “No fruit.” He eats apple strudels in Milan and desires better pastries in Paris. Orange sodas and sherbets. He keeps on drinking fizzy, sugary beverages, even though they bother his stomach. It is always unbearably hot out. In Milan, his passion for iced drinks punishes him: He drinks one grenadine and two aranciatas in the theater, one in the bar on the Corso Emanuele, one sherbet in the coffeehouse in the Galleria, one French Thierry mineral water. Brod is horrified by Kafka’s constant consumption of fruit and iced drinks in sultry (and, to Brod, awful) Milan. Brod wants to heed the warnings not to eat fruits or vegetables. He is intensely phobic because of the news abroad, leaked in the German newspapers, about the Italian government covering up the cholera epidemic. In the years since, it has been speculated that sixteen thousand people died of cholera in Italy in 1911—perhaps 2,600 people between May and September in Naples alone. Thomas Mann was in Italy that same summer, and he sets Death in Venice amid this same sweltering paranoia: “Obsessed with obtaining reliable news about the status and progress of the disease, he went to the city’s cafés and plowed through all the German newspapers, which had been missing from the hotel lobby during the past few days.” It is the temptation of a strawberry that finally kills Mann’s Gustav von Aschenbach, a cause of death modeled on Gustav Mahler, who died just that May in Vienna. It’s amusing that the usually hypochondriacal Kafka is so flippant about cholera, unlike Brod, hysterically applying Vaseline to his mosquito bites. They are irritated with each other over these twenty-four hours in Milan, bickering constantly. Kafka convinces Brod to climb to the top of the cathedral in ninety-five-degree heat, and yet he later concedes that the cathedral, with all its spires, was “a little tiresome.” Outside of the shopping arcade with the glass domes at Cathedral Square, Brod begs Kafka to promise that if he dies, he will be administered a lethal heart injection, like Mahler had requested for himself, to make sure he is really dead. They decide instead to return to Paris, despite the disaster of the previous year, where Kafka writes in his travel diary of yearning to go about the side streets looking for fruit.

BROTHEL

Then there is the cubist centerpiece of fruit at the bottom of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the painting Picasso worked on for years that he thought of as a “philosophical brothel.” It’s a strange little gesture, like a sneer or tribute to mannered composition (Here you are, Cézanne). Kafka’s description of the prostitutes in Milan (disdain) versus the next passage on fizzy drinks (delight). Everything feels paradoxical. “The girls spoke their French like virgins. Milanese beer smells like beer, tastes like wine.” Kafka sketches quick portraits of the women in a way that also calls to mind Degas’s brothel monotypes, especially the one with the four faceless, naked women seated, legs akimbo, arms crossed, the focus on the black triangles of their bushes. A long, winding description that reads like a sketch for one of the later novels—a seated girl, her belly “spread shapelessly over and between her outspread legs under her transparent dress.” He is fascinated by the “round, talkative, and devoted knees” of a Frenchwoman, her talent for thrusting money into her stocking. He fixates on an old man’s hands on her knee. A sinister Spanish woman with a sinister Spanish face stands by the door, body stretched in a sheath of “prophylactic silk.” At home, “it was with the German bordello girls that one lost a sense of one’s nationality for a moment, here it was with the French girls.” The three-quarter circle in which the unengaged girls stood around the two visitors, crowded together closely, drawing themselves up in certain postures, like the five women of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Picasso owned eleven of the fifty or so extant Degas monotypes. The word bordel is associated with chaos. Perhaps this essay (or is it a story?) reads like a bordello, all these figures crowded together.

DREAM

Months after this Paris trip, Kafka dreams of walking through a row of houses to a brothel, a gigantic row of rooms without doors, rooms with dirty rumpled beds. In the dream, there are two women on the floor, Max Brod is with one, Kafka with the other. He runs his fingers across the woman’s legs and presses her thighs in a regular rhythm. “My pleasure in this was so great that I wondered that for this entertainment, which really after all was the most beautiful kind, one still had to pay nothing,” he writes. The woman sits up, then turns her back to him. To his “horror,” it was “covered with large sealing-wax-red circles with paling edges, and red splashes scattered among them.” He begins pressing his thumb all over into these spots, noticing too that there are “little red particles—as though from a crumbled seal” on his fingers as well. Suddenly, he observes Brod on the floor eating a rather chunky potato soup.

FIGURE

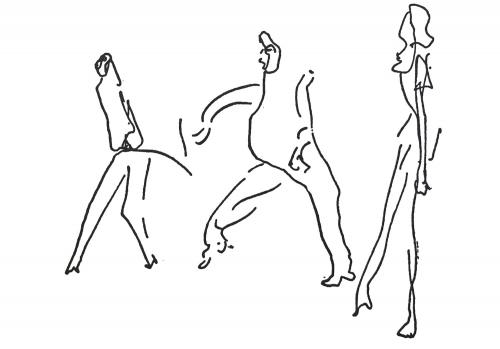

In his published conversations with Kafka, Gustav Janouch recalls seeing an exhibition with Kafka featuring Picasso’s exuberant pink-fleshed giantesses with oversized feet. Janouch remarks that Picasso was a “willful distortionist,” to which Kafka apparently replies, “He only registers the deformities which have not yet penetrated our consciousness.” In his diaries, and later, the literary works, Kafka trains a fragmenting gaze on women’s faces and bodies especially. The figurative doodles in Kafka’s diaries (see page 58), a few of which are printed in the English translation, look like sketchy embodiments of the photographs from Jørgen Peter Müller’s My System, the 1904 book of exercises by the Danish gymnast that Kafka followed religiously, performing naked calisthenics in front of his open window, even in winter. Back in Prague, having returned from the second trip to Paris, he continues writing sketches of his brothel visits in his diary. Girls “dressed like the marionettes for children’s theatres that are sold in the Christmas market, i.e. with ruching and gold stuck on and loosely sewn so that one can rip them with one pull and they then fall apart in one’s fingers.” A “landlady with the pale blonde hair,” her “sharply slanting nose…in some sort of geometric relation to the sagging breasts and the stiffly held belly.” Entries at the theater in Milan that conjure the black-shadowed realism of Manet. “Tall, vigorous actor with delicately painted nostrils; the black of the nostrils continued to stand out even when the outline of his upturned face was lost in the light. Girl with a long slender neck ran off-stage with short steps and rigid elbows—you could guess at the high heels that went with the long neck…Nose and mouth of a girl shadowed by her painted eyes. Man in a box opened his mouth when he laughed until a gold molar became visible, then kept it open like that for a while.” Kafka notices what everyone’s wearing at the theater—always in his diaries an attention to clothes. In a Prague entry, he observes a large button on a dress, paired with American boots, and wishes he could create something as beautiful in writing as this mere button. But especially he observes the faces of women in uncomfortable detail, a surgical gaze he later trains on the feminine figures in his fiction. He is obsessed with Semitic features. He observes that a young Italian woman’s “otherwise Jewish face became non-Jewish in profile.” He writes an entire paragraph in an extreme close-up about the way she stands up and leans forward. She is reading a paperback detective story that her brother had been begging to read. Her father has a “hooked nose,” but hers, being gently curved, is “more Jewish.” Women especially have masks in Kafka’s work. In his diary a year later, after meeting his future fiancée Felice Bauer in the Brod living room: “Bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly…Almost broken nose.”

In his published conversations with Kafka, Gustav Janouch recalls seeing an exhibition with Kafka featuring Picasso’s exuberant pink-fleshed giantesses with oversized feet. Janouch remarks that Picasso was a “willful distortionist,” to which Kafka apparently replies, “He only registers the deformities which have not yet penetrated our consciousness.” In his diaries, and later, the literary works, Kafka trains a fragmenting gaze on women’s faces and bodies especially. The figurative doodles in Kafka’s diaries (see page 58), a few of which are printed in the English translation, look like sketchy embodiments of the photographs from Jørgen Peter Müller’s My System, the 1904 book of exercises by the Danish gymnast that Kafka followed religiously, performing naked calisthenics in front of his open window, even in winter. Back in Prague, having returned from the second trip to Paris, he continues writing sketches of his brothel visits in his diary. Girls “dressed like the marionettes for children’s theatres that are sold in the Christmas market, i.e. with ruching and gold stuck on and loosely sewn so that one can rip them with one pull and they then fall apart in one’s fingers.” A “landlady with the pale blonde hair,” her “sharply slanting nose…in some sort of geometric relation to the sagging breasts and the stiffly held belly.” Entries at the theater in Milan that conjure the black-shadowed realism of Manet. “Tall, vigorous actor with delicately painted nostrils; the black of the nostrils continued to stand out even when the outline of his upturned face was lost in the light. Girl with a long slender neck ran off-stage with short steps and rigid elbows—you could guess at the high heels that went with the long neck…Nose and mouth of a girl shadowed by her painted eyes. Man in a box opened his mouth when he laughed until a gold molar became visible, then kept it open like that for a while.” Kafka notices what everyone’s wearing at the theater—always in his diaries an attention to clothes. In a Prague entry, he observes a large button on a dress, paired with American boots, and wishes he could create something as beautiful in writing as this mere button. But especially he observes the faces of women in uncomfortable detail, a surgical gaze he later trains on the feminine figures in his fiction. He is obsessed with Semitic features. He observes that a young Italian woman’s “otherwise Jewish face became non-Jewish in profile.” He writes an entire paragraph in an extreme close-up about the way she stands up and leans forward. She is reading a paperback detective story that her brother had been begging to read. Her father has a “hooked nose,” but hers, being gently curved, is “more Jewish.” Women especially have masks in Kafka’s work. In his diary a year later, after meeting his future fiancée Felice Bauer in the Brod living room: “Bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly…Almost broken nose.”

PHOTOGRAPH

While still a young law student, Kafka was crazy about a twenty-one-year-old wine-bar hostess who went by the nickname Hansi. (She in turn called him Franzi.) He often visited her in her room, where she spent entire days in bed, a detail he stores away for the character based on her in The Trial. She is actually in the other half of the photograph of Kafka the dandy, posing with a dog between them. They are both petting the dog, a panting German shepherd. Hansi wears a pillbox hat suspended over an elaborate braided coiffure, a smart buttoned suit and tie (her work uniform, perhaps). She is slightly out of focus. It is difficult to know whether her smile is of a professional variety, or something more intimate. Maybe she is laughing. In the complete portrait, Kafka looks rather debonair, even mischievous. In most photographs published in biographies and circulated online, Hansi and the dog have been cropped out entirely. In some versions, Kafka’s body has also been cropped, just a floating pale head with a bowler hat. In others, he is shown with the dog, absent Hansi. That movement to make this photograph one of solitude, what does it say? Do we desire our Kafka unhappy and alone?

In the complete portrait, their hands are on the dog, perhaps to keep him from lunging at the photographer. Picasso originally intended to put a dog in his philosophical brothel painting—he did numerous sketches of dogs for the work. In one, a dog humps the leg of a male visitor, often referred to as the medical student, who is ultimately omitted from the final painting. There are several sketches in which the dog is nursing puppies. The blurriness of the dog in this portrait reminds me of one of Francis Bacon’s ghostly dog paintings, inspired by the nineteenth-century photographic studies of human and animal movement by Eadweard Muybridge, which Bacon kept as references in the living ruin of his studio. Muybridge stills motion in multiple frames, which Bacon enfolds in a single image. Muybridge’s most absurd study is of a naked woman feeding a dog, as seen from three angles, which I now associate, in my mind, with Hansi.

STATUARY

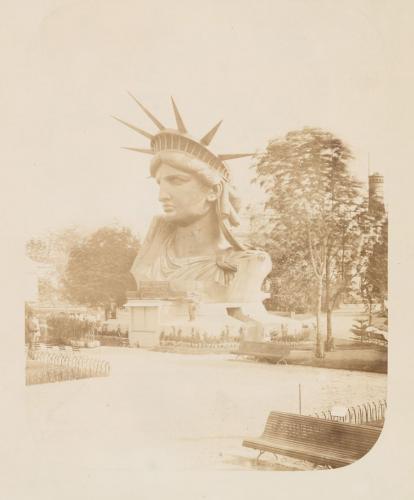

The Prague wine bar where Hansi was a hostess was named the Trocadero, which shares its name with the Palais du Trocadéro in Paris, built for the 1878 World’s Fair. Kafka was impressed by this colossus of Moorish design when he visited Paris, or perhaps he felt drawn to the site because it reminded him of his favorite wine bar back home. Within the gardens of the old palace were two large statues, a rhinoceros and an elephant, now in front of the Musée d’Orsay. At some point in the nineteenth century, the head of the Statue of Liberty was also exhibited in those same gardens. There’s something uncanny about photographs of such an iconic monument without a torso, unable to raise her phantom arm, her large head dwarfing the park benches and trees, like Kafka’s opening image of the Statue of Liberty holding a sword instead of a flame in his unfinished novel Amerika. Picasso used to frequent the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, located within the old palace, where he first discovered the African Fang masks that partially inspired his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Photos of the museum show a cluttered space, like a junk shop, crowded with statues of hybrid animal-human figures. When Picasso first stepped inside, he wanted to leave immediately, the smell of dampness and rot stuck in his throat. When thinking of W. G. Sebald’s story about Kafka in Vertigo, the postcards and photographs cluttering the page, it too feels like a junk shop. The internet, repository of old and displaced images, is another sort of junk shop. I wonder why I’m trying to make sense of this detritus.

The Prague wine bar where Hansi was a hostess was named the Trocadero, which shares its name with the Palais du Trocadéro in Paris, built for the 1878 World’s Fair. Kafka was impressed by this colossus of Moorish design when he visited Paris, or perhaps he felt drawn to the site because it reminded him of his favorite wine bar back home. Within the gardens of the old palace were two large statues, a rhinoceros and an elephant, now in front of the Musée d’Orsay. At some point in the nineteenth century, the head of the Statue of Liberty was also exhibited in those same gardens. There’s something uncanny about photographs of such an iconic monument without a torso, unable to raise her phantom arm, her large head dwarfing the park benches and trees, like Kafka’s opening image of the Statue of Liberty holding a sword instead of a flame in his unfinished novel Amerika. Picasso used to frequent the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, located within the old palace, where he first discovered the African Fang masks that partially inspired his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Photos of the museum show a cluttered space, like a junk shop, crowded with statues of hybrid animal-human figures. When Picasso first stepped inside, he wanted to leave immediately, the smell of dampness and rot stuck in his throat. When thinking of W. G. Sebald’s story about Kafka in Vertigo, the postcards and photographs cluttering the page, it too feels like a junk shop. The internet, repository of old and displaced images, is another sort of junk shop. I wonder why I’m trying to make sense of this detritus.

HEAD

On September 7, 1911, the night before Kafka and Brod arrived in Paris, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire was arrested under suspicion of stealing the Mona Lisa. His friend Picasso was also detained. The painting had been stolen two weeks before, on August 21. A week after the painting was stolen, a Belgian, Géry Pieret, who had worked as a kind of secretary to Apollinaire, wrote an anonymous letter to Le Journal confessing to stealing an ancient Iberian statuette from the Louvre, bragging about the museum’s lax security. Apollinaire, reading this in the newspaper, then realized that Pieret had most likely hidden the statue in his house. Several years earlier Pieret had sold him two such ancient Iberian stone heads—a female and male head, even though Picasso only wanted the female head. (The elongated ears and fixed oval eyes of the two central figures in his philosophical brothel painting were inspired by these heads.) Picasso and Apollinaire became paranoid that they would be accused of conspiring in an art-trafficking ring, and initially planned to flee. They then decided to pack up the statues in a suitcase, wait until midnight, and then throw them in the Seine when no one was looking, a madcap plan also aborted. Finally Apollinaire took the sculptures to Le Journal’s officesso that they could be anonymously returned to the Louvre, although by then Picasso just wanted to keep them. By that evening, Apollinaire was in jail, accused of being the chief of an international gang seeking to despoil the museums of France. He was strip-searched and incarcerated for several days inside La Santé, the Paris prison, and kept in solitary confinement. The prison registry referred to him as Apollinaris Kostrowitsky, his Polish name, prisoner 216. Picasso was also arrested, but immediately released. On September 12, Apollinaire was brought before the judge to be interrogated. That morning, a plainclothes policeman went to serve a terrified Picasso with a summons to appear. Various accounts depict a collapse in the courtroom—a hysterical Apollinaire standing before the magistrate, confessing to anything the authorities wanted. Apparently Picasso, also a wreck in front of his handcuffed friend, denied even knowing him. For a long time afterward, Picasso was convinced he was being followed by police and only went out at night in a taxi, switching cars several times to throw off the tail. Apollinaire was also haunted by his interrogation and imprisonment. Some accounts suggest he volunteered for the French army during World War I in order to erase somehow the stigma of the unsavory foreigner. As I stare at a photograph of the stolen female stone head with its plaited braid, I keep returning to the photograph of Hansi the waitress, her elaborate braided hairstyle. Their uncanny likeness.

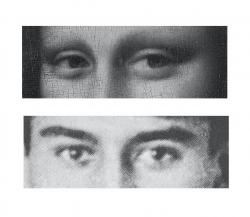

THE MONA LISA IS MISSING!

On his second trip to Paris, young Kafka visited the Louvre weeks after the Mona Lisa was stolen. When I first read this detail, I imagined him standing meditatively in front of a blank space, staring at the painting’s absence, at the spare poetry of the four remaining hooks. But recalling this Louvre visit later in his diary, he focuses on the spectacle of the crowd in the Salon Carré, “the excitement and the knots of the people, as if the Mona Lisa had just been stolen.” The Mona Lisa, after all, only really became the Mona Lisa once she was stolen. Her mysterious expression and sedately folded hands multiplied on advertisements, candy boxes, postcards. That night, Kafka and Brod stood in line at the Omnia Pathé to see the five-minute film Nick Winter and the Theft of the Mona Lisa, in which the thief returns because he took the wrong painting—he takes Velázquez’s Infanta Margarita instead. Is Kafka standing in front of the blank space that different than what it’s like to stand in the crowds in front of the Mona Lisa now? Is it possible to stand in front of that work and really see anything? Is this perhaps part of the allure—the mystery and blankness of her face? I realize writing this that Kafka too is someone I project my thinking and desires onto.

On his second trip to Paris, young Kafka visited the Louvre weeks after the Mona Lisa was stolen. When I first read this detail, I imagined him standing meditatively in front of a blank space, staring at the painting’s absence, at the spare poetry of the four remaining hooks. But recalling this Louvre visit later in his diary, he focuses on the spectacle of the crowd in the Salon Carré, “the excitement and the knots of the people, as if the Mona Lisa had just been stolen.” The Mona Lisa, after all, only really became the Mona Lisa once she was stolen. Her mysterious expression and sedately folded hands multiplied on advertisements, candy boxes, postcards. That night, Kafka and Brod stood in line at the Omnia Pathé to see the five-minute film Nick Winter and the Theft of the Mona Lisa, in which the thief returns because he took the wrong painting—he takes Velázquez’s Infanta Margarita instead. Is Kafka standing in front of the blank space that different than what it’s like to stand in the crowds in front of the Mona Lisa now? Is it possible to stand in front of that work and really see anything? Is this perhaps part of the allure—the mystery and blankness of her face? I realize writing this that Kafka too is someone I project my thinking and desires onto.

LOUVRE

It’s not an easy task to reconstruct what artworks Kafka refers to in the brief list he makes while at the Louvre. I spend weeks puzzling over his notation “Velázquez: Portrait de Philippe IV roi d’Espagne 1599–1600,” finally discerning that the Louvre once owned a copy of a painting once attributed to Velázquez—Portrait of Philip IV in Hunting Costume—but which is now attributed to Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, the Spaniard’s assistant and son-in-law. The original and better-known Philip IV in Hunting Costume is at the Prado in Madrid. You can tell the difference between the nearly identical fishy-faced twirly-mustached Philip IVs, both posed with guns and dogs at their feet, by the fact that the king holds his cap in the copy and wears it in the original. Mazo’s portrait inspired Manet when he was a copyist at the Louvre for his own etching of Philip IV in Hunting Costume. I have no idea why Kafka jotted down these titles in his diary. All I can do is follow the dogs on the edges of certain paintings he writes down. The dog at Philip’s side, signaling nobility, is a mastiff much like the sleepy canine in Velázquez’s Las Meninas. The dog playing in the foreground in Rubens’s The Kermesse, a bawdy village wedding scene I imbue with a weird and layered Kafka physicality, inspired by Flaubert. But am I trying to see a Kafka gaze where there is none?

HAND

For his Madame Brunet, often referred to as the French Mona Lisa, Manet imitates the leather glove of Velázquez as well as the pose, the distant landscape. Hermann Kafka’s fancy-goods store sold gloves, along with haberdashery, parasols, umbrellas, walking sticks, silk handkerchiefs, silk ribbons, scarves, lace, buttons, slippers, fans, jewelry, and elegant decorative objects and knickknacks made of cast iron, bronze, zinc, silver, leather, wood, ivory, glass, and lead. In Sentimental Education, there are numerous descriptions of Frédéric’s gloves, “for the gloves that he had ordered were of beaver, whereas the right kind for a funeral were floss-silk.” Kafka wrote happily to a friend that he didn’t need gloves anymore when outside in the cold air, how toughened he had become by the Müller technique. The clinical horror of illustrated cut-off fingers accompanying Kafka’s technical essay from 1910, “Measures for Preventing Accidents for Wood-Planing Machines.” In his diary, Kafka quotes from an old notebook: “Now, in the evening, after having studied since six o’clock in the morning, I noticed that my left hand had already for some time been sympathetically clasping my right hand by the fingers.”

SENTENCES

All that fall in 1911, Kafka goes over to Max Brod’s to work on the travel diary. The writing is going badly in several ways. Often he writes of his imperfect sentences as being full of holes, like spatial things “into which one could stick both hands; one sentence sounds high, one sentence sounds low…one sentence rubs against another like the tongue against a hollow or false tooth; one sentence comes marching up with so rough a start that the entire story falls into sulky amazement.” It causes him physical pain to listen to Brod read from a story of his at a friend’s house. Kafka rationalizes that this is because he doesn’t have the time and quiet to draw out all of the great force and possibilities of his talent, in which, despite his doubts, he maintains his faith. “I finish nothing because I have no time and it presses within me,” he writes. This will become a refrain over the next two years (“Wrote nothing today…Nothing.”) He longs to write a story that is large and whole, well-shaped, healthy, and then he will never attempt to disavow this piece of writing.

SLEEPLESSNESS

Upon his return from traveling, Kafka experiences a period of insomnia, which he ascribes to his renewed commitment to writing: “No matter how little and how badly I write, I am still made sensitive by these minor shocks, feel, especially towards evening and even more in the morning, the approaching, the imminent possibility of great moments.” He falls asleep, wakes up an hour later. It will take one year for him to feel what he has longed for, the full force of his language. His ecstasy once he has conquered time, staying up all night writing. He writes the story “The Judgment” in one sitting, eight straight hours overnight, in September 1912, one year after his Paris trip. His legs grow so stiff that, come morning, he can’t pull them out from under the desk. The fearful strain and joy he experiences then.

THE MAN WHO DISAPPEARED

Around this time—along with complaints about the asbestos factory he now must manage, the tensions this causes with his family, his regular job, and Felice—Kafka worries constantly about how much time the publishing of his first, small book of stories, Meditation, has drained from his literary potential. When confronted with the possibility of publishing his writing, he feels panicked about how little has accumulated in his notebooks. The artifice, he vents to himself, of trying to prepare a text for publication, when what he desires is a new prose, to let a work take shape unforced. He doesn’t tell his new publishers this, but for a while now he’s been thinking about a novel, which he titles The Man Who Disappeared or The Missing Person, set in the America he has never visited. He doesn’t tell his publishers this because they would have wanted the novel before anything else. Kafka wants to keep the novel hidden, a dream, like the dream he had several years earlier of two brothers, one who went to America and the other locked up in a European prison. Thinking of Kafka’s yearning for this potential novel, was there any book he could have written that would have fulfilled his desires? Or was his longing toward literature something more impossible, or infinite?