1.

My wife said she would buy the flowers herself (the Dalloway meme come nearly full circle), walking out with a mask and gloves from the kitchen drawer. She returned with a bunch of tulips of an unusual shade of pink and orange.

We live in a small town in upstate New York. We don’t have the kind of packed urban neighborhoods where each evening people stand on stoops or balconies to ring bells and cheer the city’s frontline workers who’ve been sacrificing so much. Not for us, then, the confinement of small spaces, but also not the catharsis of a citywide expression of thanks and even of joy.

My home is across from the college campus where I teach, nearly deserted now. I sometimes see my neighbors, all of us affiliated with the college, when stepping out with our kids or walking our dogs. There are no sirens, no signs of anxiety. The world comes to us in the form of bad news.

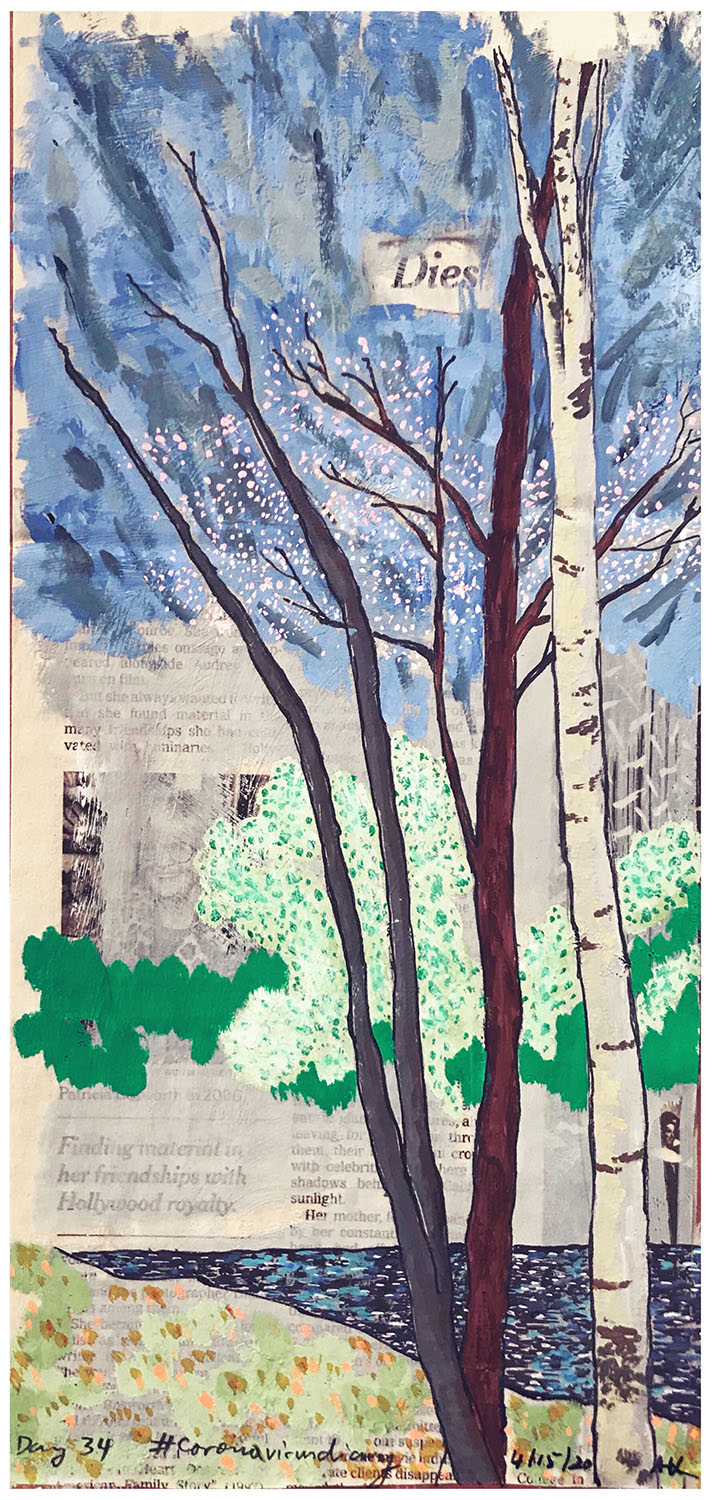

The pandemic’s obituaries page is full of written portraits of the disease’s death toll, from South Africa to Senegal to Japan. The simplest, most direct thing I can say is that while I cannot stand outside my door at 7 p.m. clapping my hands, I can at least pay tribute through painting. To the nameless dead, let me draw a single flower.

True, too, that I returned to painting, an indulgent hobby, if for nothing than for my own sanity. And yes: These are, in a way, erasures, using gouache, which is more opaque than ordinary watercolor, covering some details while allowing certain words to stand out in greater relief. I’m trying to find focus. When this lockdown started, I read that “in the age of social media, misinformation spreads a thousand times faster than the virus.” WHO believes that it is confronting an “infodemic.”

Reading the obits, then, is an attempt to slow-jam the news, slow down its consumption. Consider. The details of their lives and, with care, finding where this gesture intersects attentively with the lives of others, the words, the art of the obit, in a shroud.

2.

In late February on a chilly evening in nearby Tivoli, I was in a public conversation with Jenny Offill to celebrate her novel Weather. The narrator, Lizzie, is a librarian who does research for a mentor’s doom-laden podcast about climate change, and whose dire observations are often about disaster psychology and survivalist strategies. At the end of our conversation, Offill read aloud this little section from her book titled “What to Do If You Run Out of Candles”:

“A can of tuna can provide hours of light. Stab a small hole in the top of an oil-packed tuna can, then roll a two-by-five-inch piece of newspaper into a wick. Shove the wick into the hole, leaving a half inch exposed. Wait a moment for the oil to soak to the top of the wick, then light with matches. Your new oil lamp will burn for almost two hours and the tuna will still be good to eat afterward.”

This fragment haunted me during the first days of our enforced isolation. I hadn’t shown any foresight, hadn’t stored any food. At the grocery store, many of the shelves were bare. No chicken, no canned beans. Not even tofu, which baffled me for some reason. And certainly no wipes or gloves. I bought several cans of tuna. I was sure I had newspaper at home that I could fashion into wicks.

At the start of the coronavirus crisis, someone tweeted about a sign from her drama school: wash your hands like you convinced your husband to murder the rightful king and you can’t get the blood off.

It is my belief that literature will always save your life. This might just be my professional bias, but in this new world, where we are told not to touch for fear of contagion, I find a greater purpose in using words.

Today I asked Offill how she was doing. She said she hadn’t gone to a regular grocery store in weeks. On a walk with her husband, they passed cattails, and she remembered telling him that one could eat cattails if they were green, like corn on the cob. When they returned from the walk they looked it up in the book, and noticed there was a caveat: “Butter and salt them and eat them like corn on the cob. However, they will not taste like corn on the cob.”

3.

The arc of the moral universe is long, but during these times it definitely bends toward bad news. Two recent headlines: “In Lockdown Desperation, Migrants Pick Bananas Trashed Near Delhi Cremation Ground” and “Zoo May Feed Animals to Animals as Funds Dry Up in Pandemic.” And from a day earlier, this piece of awful news from a list compiled in a weekly review: “A woman who died alone in a nursing home recorded over 40 messages on an Alexa, many of which asked the device to relieve her pain.”

How to respond to bad news? The worst is smug condemnation of those who are suffering. In late March, India put 1.3 billion people under sudden lockdown, with buses and trains halted, leaving millions of poor daily-wage workers helpless. They were without work or money. We saw footage of thousands on the roads, walking, in some cases, hundreds of miles home. One worker said, “Our people will die of hunger before they are killed by the coronavirus.” But the pious elite in India couldn’t understand why the workers were massed on the road during lockdown. What came to mind then were the opening lines of Warsan Shire’s poem “Home”: “no one leaves home unless / home is the mouth of a shark / you only run for the border / when you see the whole city running as well.”

A more desirable response is the search for solace. That is the only reason I can forgive all the pictures of homemade, freshly baked bread that people have been posting on Facebook. I have a special fondness for Yo-Yo Ma’s videos on Twitter, playing what he calls #SongsOfComfort. But also a more ordinary happiness. A delicious, hot meal served to a tired nurse after her work in the ER. A delivery man pausing, coffee in hand, to look at the sky—or a note of thanks and a generous tip. Many are now reading the novel The Plague by Albert Camus. In the middle of the pestilence, the doctor in the book, Bernard Rieux, and his friend Jean Tarrou, go for a swim in the sea. They are mindful of the pain around them but they also hang on to life. Camus says that theirs is “a happiness that forgot nothing.”

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.