1.

All summer I found thousands of four-leaf clovers. I had been living at a firehouse since COVID-19 broke out, volunteering as a paramedic. One slow shift, my EMT partner Sam and I found a couch on a grassy hill overlooking a leveled construction site. It faced west, so we sat and watched the sun sink. All year I visited that couch—parks and cemeteries too—looking for a place to grasp what was happening in the world. There was no nearby mountaintop.

Virginia summers are generously alive, green swirling, churning, twisting over itself, seeping from the ground. Picking blackberries at night, the darkness that conceals the berries equally disguises the thorns. I froze gallons of wild berries for February—the most difficult month—when I am often overcome with an unmoving restlessness. “I wish I knew more about your hopes and dreams, and perceptions of everything around you,” my mom wrote in a letter. My sister harvested parsley one lazy Saturday. “Other than the parsley,” she wrote, “I don’t have plans.”

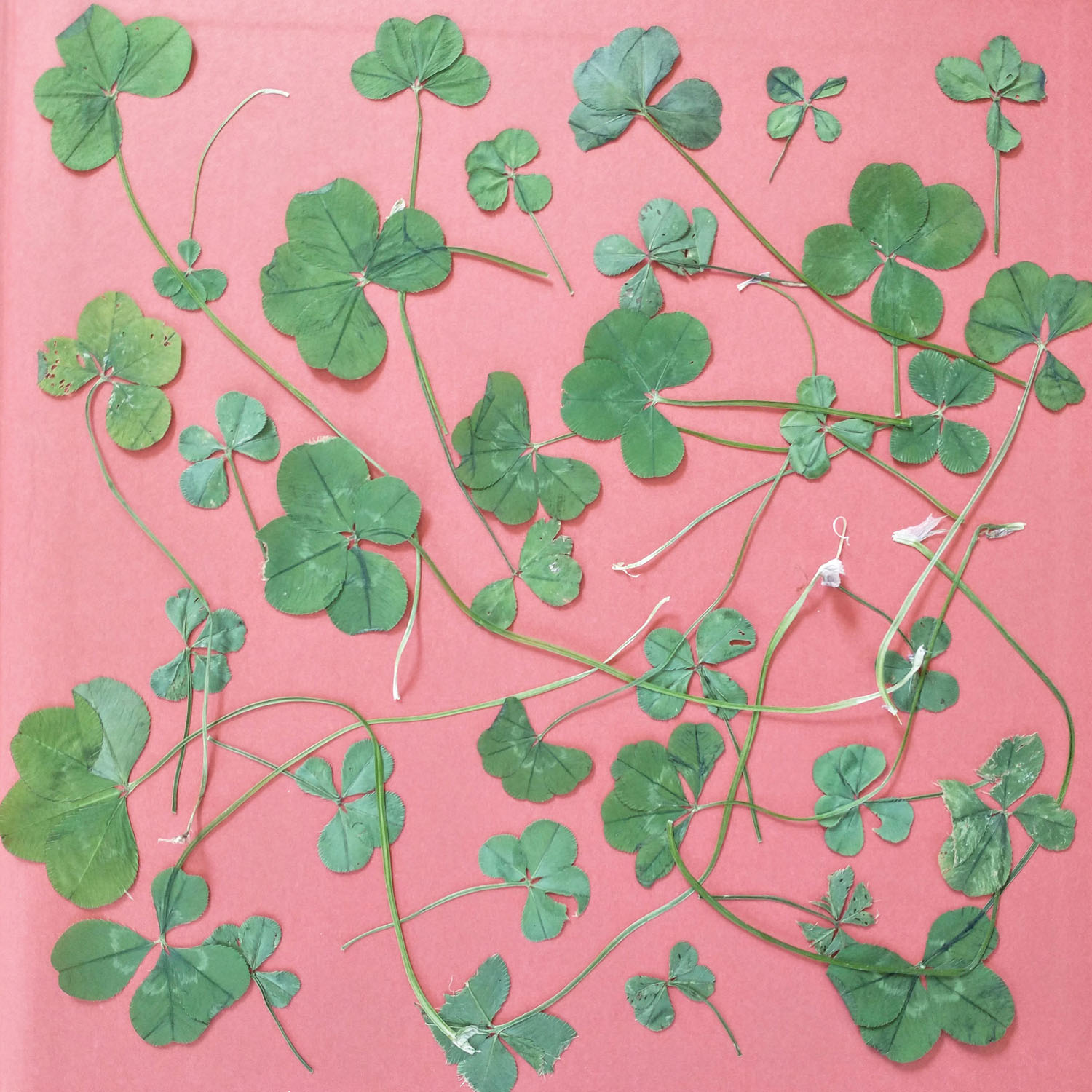

Under garish midday light, I visited a grave too young for a stone. The Hillsboro Cemetery is fenced and full of family names in clusters: Stone, Potts, Tribby; James, Lemon, Webb. A man alive in 1786; a baby boy born and in thirty days dead. Annie L. Camp’s grave said simply her name, 1861–1932 and in the lower right corner: rest. I knelt to the grass and saw seven four-leaf clovers growing from a grave.

Like my patients, Kathy M. Hagenbuch is a stranger. She died July 15 at age fifty-three, and has a husband and teenage son. In 2017, she posted a photograph on social media of a green sign in a gray, snowy landscape that said: you are now crossing the 45th parallel, halfway between the equator and north pole. A line so important she took a picture but so invisible she needed to be told. I sat near her grave on a thin, living layer of dirt between me and the underground. I thought about many fine lines: living/healthy/death, suffocation/holding our breath. The cemetery is locked after sundown—as if we could keep out the living, as if we could keep in the dead.

2.

Early autumn, the days began to blend into a long, continuous strand of blurry sound and waning light. The 911 calls we’d run earlier in a shift would feel like a lifetime ago. I struggled to remember. After shift-change one morning, I took a long drive, slow and easy, stopping many times along the way. There was a crash on Route 81 northbound that made the highway a parking lot four miles back. I was glad not to be responding to it. I took the next exit, then turned off a nowhere main road and followed signs to Resurrection Cemetery.

Leaves fell like glitter, pale sunlight the color of my hair. Fields of ground-level gravestones were bedded in soft grass, clover and thyme. The clover was a delicate variety, with round leaves that grew into each other. Sitting in the grass, I caught sight of many false four-leaf clovers that, on closer look, were several threes. The trees and mountains were green with creeping color: pale gold, orange, olive, grape. Gaudy bouquets of fake flowers adorned nearly every grave. Several of the graves had Happy Birthday balloons. Someone had placed a bottle of Coca-Cola at the grave of Medard Kyle Kowalski, meds, who would have been twenty-three on September 16, but instead died on December 1, 2014, at seventeen. I picked up a green acorn and wondered: What’s the difference between an acorn and a corpse?

I sat on a stone-bench memorial for Kyle Derek Edmunds, forever in our hearts, and breathed, thinking about what a struggle that was for my COVID-19 patients. A funeral procession arrived, a hearse and several dozen cars. The strangers, the burials—it’s hard not to feel removed from it all. In 911, we rarely get closure. After each call, I write a patient-care report, a sad excuse for the story. Later I find myself in cemeteries, wondering about a patient’s friends or favorite color, the faces in photographs on their apartment walls. At Resurrection Cemetery, my phone pushed a 911 notification—UNCONSCIOUS PERSON—this time for another paramedic to respond. I’m trying to be more conscious; I’m trying to be more kind. A cemetery monument said unutterable tenderness. That and September sky.

3.

By winter, the grass had fully grown over Kathy M. Hagenbuch’s grave. Construction had shaken the cemetery all year, but this evening it was quiet, hushed. I sat among the graves. I had built summer herb and vegetable gardens at the firehouse, but six months later they were dead. The chief sent me the obituary of a young trauma patient. I stared at it blankly for a long time, disoriented, trying to comprehend this single stranger’s death. One night I spread newspapers under a canvas to paint and saw Kathy M. Hagenbuch’s photograph and obituary. There’s a traffic circle next to the cemetery, like a compass rose with exits east, west, north, and south. On the gravestones, so many of the strange names I have seen in death but never living: Easterday, Love, Downs, Lemon, Creamer, Spring. The sun settled; shadows stretched.

My last paramedic shift of the year, I gave up on sleep around 2 a.m., left my bunk room and wandered the station. In the kitchen, I heated a bowl of angel-hair pasta and sat at the heavy wooden table. My head ached. I heard another bunk-room door close, and Sam came into the kitchen in socks. He couldn’t sleep either, he said. We decided to take a drive. We drove road to road, parking lot to parking lot, traveling in small and large loops around the county. “Take it to the Limit” played on the radio…“Gloria”…“Sweet Home Alabama”…“Let Her Go.” Frost sparkled in the headlights. Crossing the quiet intersection of Belmont Ridge and Hay Road—the site several months prior of a horrible car wreck with a trauma code—a star shot across the sky. A 911 incident was dispatched and we read the notes—COVID-19—then watched the icons of the nearest ambulance and fire engine turn yellow, then red, as they responded. We stopped and walked through a football field. The leather radio strap with an engraved lucky clover, a gift from Sam, was a comforting weight on my shoulder. 4:30 a.m., we idled outside a music store, waiting for Dunkin’ Donuts to open at five. When it did, we got coffee and drove to the sunset couch, abandoned and overlooking a barren construction site. Backs to the sunrise, we sat and watched the stars.

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.