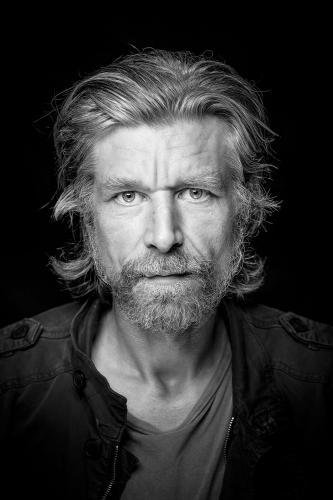

The serial publication of the six volumes of My Struggle—four of them so far translated from Norwegian into English—has been one of the most exciting developments in contemporary fiction. The books recount, not always chronologically, the childhood, adolescence, first and second marriages, and fatherhood of a character who shares author Karl Ove Knausgaard’s name, family, and history. Not quite an autobiography, My Struggle contains invented dialogue and details that it would have been impossible for Knausgaard to remember. The volumes span 3,600 pages, and leisurely attention is given to such activities as childhood play, a teenage attempt to procure alcohol for a party, dinner conversation, visits to grandparents, a music class with one of his young daughters, and much more of everyday life past and present.

The serial publication of the six volumes of My Struggle—four of them so far translated from Norwegian into English—has been one of the most exciting developments in contemporary fiction. The books recount, not always chronologically, the childhood, adolescence, first and second marriages, and fatherhood of a character who shares author Karl Ove Knausgaard’s name, family, and history. Not quite an autobiography, My Struggle contains invented dialogue and details that it would have been impossible for Knausgaard to remember. The volumes span 3,600 pages, and leisurely attention is given to such activities as childhood play, a teenage attempt to procure alcohol for a party, dinner conversation, visits to grandparents, a music class with one of his young daughters, and much more of everyday life past and present.

All of this is surprisingly interesting, even addictive, as has often been pointed out in reviews. But no one can pinpoint precisely why. A striking element in the praise of Knausgaard—and he has garnered almost uniform praise in the English-speaking press—is the recourse to vocabulary not normally considered complimentary. “Boring” comes up an enormous amount. James Wood of the New Yorker wrote of Book One that “even when I was bored, I was interested.” Other terms that get used are “self-aggrandizing,” “sloppy,” “lack of selection,” “lack of structure,” “intermittent meaninglessness,” “cliche,” and “banal.” Again, these are all quotes from highly laudatory reviews.

Those who haven’t fallen under Knausgaard’s spell repeat those words and add more slicing ones of their own. In the Nation, William Deresiewicz claimed that Knausgaard is “utterly insensible to other people” and that his work is the product of “modern self-inflation.” Becca Rothfeld, formerly assistant literary editor for the New Republic, wrote for the site Hyperallergic that My Struggle is “insultingly self-indulgent.”

Let’s note here that Rothfeld by her own admission stopped reading My Struggle after the first 100 pages, which would seem to disqualify her from an authoritative opinion on its literary value. Outside of the review venues, many serious readers seem likewise ready to dismiss Knausgaard without reading his work. Whenever the subject of My Struggle comes up in my Facebook feed, which is heavily weighted toward fellow writers, there are numerous comments along the lines of “I have no intention of reading 3,000 pages of navel-gazing.” Always, at some point, someone will introduce the word “narcissism,” after which talk disperses like a crowd at a hanging after the prisoner’s neck has been broken.

Why is this term, a theft from the discipline of psychology, so readily reached for in discussing My Struggle, and why is it so often used as a trump card by those hostile to the book? At stake here is the question of how we regard autobiography and self-portraiture in fiction. I begin to suspect that narcissism, with its currency as shorthand for whatever drawbacks we find in our individualistic and individual rights-defending culture, is meant to put an end to conversation about the artistic merits or emotional power of certain literary works. These are generally works narrated by a speaker who feels uncertain in his self-definition and who examines his thoughts and his interactions with others in an attempt to forge some sort of coherence out of his desires, impulses, actions, and values. They are works that make us uncomfortable, and My Struggle is one of them.

The banality and boringness of My Struggle have been highly overstated. They are likely not really what readers, fans and nonfans alike, are reacting to when they try to articulate what seems strange or off-putting about the book. Despite its length, My Struggle is a quick and lively read. Knausgaard employs a brisk, colloquial style; characters are sketched with concision and energy. Even what is most ordinary in the novel is nearly always rooted in powerful emotions vividly recalled. The opening of Book One gives us the earliest and most persistent of these emotions: Knausgaard’s utter terror of his father, a controlling, rage-filled, sometimes physically violent man who tried to crush the least spontaneity and joy out of his two sons. This terror shadows Knausgaard’s entire childhood and perhaps accounts for his antiauthoritarian strain as a young man. It certainly accounts for his statement, both in interviews and in his book, that his primary wish for his own children is that “they shouldn’t be afraid of their father.” The long concluding section of Book One, in which Knausgaard and his older brother, Yngve, travel to the house where their father recently drank himself to death, is mesmerizing, both in the description of the days Karl Ove and Yngve spend scrubbing the place clean of rotted clothes, empty bottles, and excrement, and in Knausgaard’s honesty about his reaction to the death, which includes both unexpected grief and a sense that the bastard got what was coming to him. Some may read the details of the cleaning as banal, but how can they be when they are saturated with horror over a parent’s life ending in this kind of squalor?

Likewise, in later volumes, Knausgaard’s adolescent longing for sex and his courtship of his second wife strike deep universal tones of desire and despair. Passages about pushing a stroller through the streets of Malmö, Sweden, resonate with fears of emasculation (a sensitive topic, given Knausgaard Senior’s tendency to ridicule young Karl Ove as a sissy) as well as the fear of sacrificing one’s ambitions and ideals to the demands of caretaking.

The complaints about My Struggle’s banality are curious, given that the novel as a genre was born to give voice to the everyday. That is what differentiated it from the epic, the chivalric tale, and the morally improving allegory. The novel has always had as its aim the depiction of ordinary people. Think of the works of Jane Austen and their dances, letters, long walks, and teas. Novels bore not when they contain the banal but when the banal is not a means of conveying underlying feeling and meaning. When Knausgaard and his childhood friends shit in the woods in Book Three, delighting in examining the differences between one boy’s excrement and another’s, the point is not to force our attention upon something so everyday and undignified as normally to be banished from the pages of literature. The point is Knausgaard’s capturing of the pure animal vitality he and his playmates experienced as children. I disagree with critics who claim that Knausgaard includes “everything” in his opus. It’s true that he wrote the volumes of My Struggle very quickly and that they were not greatly edited before publication. But a natural selection surely occurred; he wrote of what was emotionally salient enough to have remained in memory. As an accomplished author with two celebrated novels behind him, Knausgaard had the skill and stamina to translate those memories into compelling scenes and minidramas.

My Struggle is not formless. The first volume, as has been pointed out by Elaine Blair in the New York Review of Books, is a kind of overture, with glimpses of Knausgaard as a child, a teenager, and an adult. Book Two employs an ingenious structure, opening with a visit to a run-down amusement park by Knausgaard; his wife, Linda; and their then three children. It soon regresses to an earlier time, a birthday party to which Knausgaard takes his elder daughter. Then it regresses again to Knausgaard’s move several years before to Sweden, in flight from his first marriage, and his budding romance with Linda. After a great deal of material on their early months together, his relationship with his mother-in-law, and the new experience of parenthood, we are brought back to the day of the birthday party and then continue full circle to the amusement park, 500 pages after we last saw it. Books Three and Four proceed more chronologically, detailing Knausgaard’s childhood, move to a new town, last years of high school, first job, and so on.

If My Struggle is not banal in the pejorative sense, nor boring, nor formless, what triggers the endless repetition of these criticisms? Perhaps it’s that it is so clearly a book about selfhood. Knausgaard has defined his project as such, to New York Times writer Larry Rohter among others: “It is a book about the construction of the self.” This is what creates such bile in its critics and such apology in its promoters. Self-construction is historically another one of the novel’s central themes, from Jane Eyre to The Portrait of a Lady to Harry Potter. But normally this theme is tricked out with fictional characters and suspenseful plots and engaging local color (Thornfield Hall, Hogwarts) to make it less stark to the reader. The construction of an imagined, interestingly costumed self is engaging to the reader and morally acceptable in the writer. When the self happens to be more or less the author’s own, readers may feel like intruders spying on matters too intimate to enjoy.

What is narcissism, anyway? Book critics like to lob the term due to its frisson of clinical pathology (technically, it means the inability to distinguish between self and external objects, or extreme grandiosity), but what they really mean by it is a level of interest in the self beyond that which they consider polite. The very fact that Knausgaard has written 3,600 pages about “the construction of a self” is taken as proof that he suffers from excessive self-regard. “How nice it would be,” jeers Becca Rothfeld of Hyperallergic, “to be afforded the luxury of narcissism—the luxury of writing about experiences that are taken, prima facie, to matter.”

In fact, Knausgaard has made it clear he often doubted that the pages he was generating for My Struggle did matter. He has many times told the story of writing the book as a desperate gambit to break through four years of writing failure that had slowed his output to a trickle. He had hoped to write a novel about his father, and the only way to circumvent his block, he discovered, was to write “stupidly”—without attention to the quality of the prose and without self-criticism. In an interview with the author Andrew O’Hagan, Knausgaard reported that he saw the work as “uninteresting” and that only the encouragement of a friend, to whom he read pages over the telephone every day, kept him going.

What made Knausgaard’s friend encourage him was clearly not just kindness. What many readers fail to see is that Karl Ove Knausgaard, the narrator of My Struggle, and Karl Ove Knausgaard, the protagonist of My Struggle, are two quite independent beings. Let’s call the latter “KOK” to help distinguish them. To be able to write freely, Knausgaard had to construct for himself a stance and a voice that were without judgment: unalarmed, unafraid, unashamed, undefended. This is precisely what makes the books work and creates our riveted attention. Knausgaard achieves a Zen-like ability to observe everything yet attach to nothing. KOK, like any normal human being, attaches to it all: his parents, his brother, music, girls at school, his own fluctuating feelings. Knausgaard transcribes these feelings and the thoughts associated with them and moves on. KOK watches himself, worrying about his clothes and his popularity; Knausgaard simply watches that watching. KOK suffers from terrible shame, but Knausgaard is not ashamed of that shame and doesn’t seek to hide it. Knausgaard writes a good deal about his excessive drinking in My Struggle, and in Book Four he explains: “Alcohol makes everything big…and the light it transmits gilds everything you see, even the ugliest and most revolting person becomes attractive in some way, it is as if all objections and all judgments are cast aside in a wide sweep of the hand, in an act of supreme generosity, here everything, and I do mean everything, is beautiful.” There are hints that in writing My Struggle Knausgaard found a method of replicating what drinking does for him. And so while there is grandiosity and self-centered behavior in My Struggle, they belong to KOK the boy or teen or young man, and the more clear-sighted yet accepting Knausgaard mines these moments in a way that is gently funny. When, as an unknown eighteen-year-old, KOK is accepted into a writing program, Knausgaard tell us: “I had expected to be accepted because although I knew what I had written might not have been that good and consequently they ought to have rejected me, it was me, however, who had done the writing and that, I felt, they would not be able to ignore.”

A different author might have signaled the irony more wildly, amping up the comic effect, or introduced a comment to assure us that he recognizes the thought as pompous. Anton Chekhov famously wrote a letter to his publisher in which he complained about the latter’s desire for more pointed moralizing in his work. “You would have me, when I describe horse-stealers, say: ‘Stealing horses is an evil.’ But that has been known for ages without my saying so. Let the jury judge them, it’s my job simply to show what sort of people they are.” Knausgaard’s desire in My Struggle is simply to show what sort of a person KOK has been, and what sorts of people his father and mother, his brother and grandparents and uncles, his school friends and adult companions and wives are as well. He does a very good job with all of those portraits. Book Four contains an excruciating scene in which the teenage Knausgaard visits his father and his father’s new girlfriend, Unni. In a ten-page passage largely of dialogue, Knausgaard captures his father’s sullen belligerence, maudlin need for forgiveness, and hounded self-deception. Knausgaard’s mother, more casually drawn throughout, still comes off vividly as an essentially empathic woman who has nevertheless willfully blinded herself to her husband’s sadism.

William Deresiewicz doesn’t buy the notion that a novel can be good if we can’t apply the fuzzy accolade of “well-written” to it. “Nothing happens in the writing,” he complains of My Struggle, mourning the absence of “the touch of literary art: by simile or metaphor, syntactic complexity or linguistic compression, the development of symbols or elaboration of structure—by beauty, density or form.”

I’m all for beauty, density, and form, for compression and music. But I’m for them in other novels. A major task of fiction is to engage our wonder and make us experience the world more fully, perhaps even to expand our idea of the human. There are many ways for fiction to accomplish this. Some involve beautiful sentences, some do not, just as music does not always have to be beautiful to be potent. Knausgaard’s sentences are not readily quotable. They do feel flat and unrevealing out of context. But he is not a clumsy writer, as some would have one believe: His prose does not distract or obscure. He may call it “stupid,” but it is stupidity with great experience behind it. The tonal control is flawless; he never wavers in the cool, judgment-free distance that allows such emotional immediacy and honesty. The struggle the novel’s title refers to is Knausgaard’s struggle between conflicting impulses, aims, and pressures; or, put another way, it is his struggle to be at one with his life. And this universal struggle he conveys with tremendous power.

The final significant strain of complaint about Knausgaard’s work has to do with gender. Okay, some readers have grumbled: The book is a solid achievement, but if it had been written by a woman, no one would have published, much less celebrated, it. This argument was put forth in a 2014 piece by Katie Roiphe for Slate. Its title was helpfully to the point: “Her Struggle: What if My Struggle by the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard were written by Carla Olivia Krauss of Cobble Hill, Brooklyn. Would we care as much?” Roiphe’s answer, naturally, was no. She believes that the gender reversal in Knausgaard’s passages about strollers and diapers and birthday parties accounts for My Struggle’s success; “if a woman wrote it,” Roiphe insists, “it would not have the same glamour; it would be drab, familiar, whiny.” The Slate article was much shared on social media, at least in my little literary community, and many writer friends I admire and respect jumped in to applaud it.

Are Roiphe et al correct? It’s very hard to claim that there’s no gender bias in publishing. The annual statistics published by VIDA: Women in Literary Arts have been eye-opening, showing a far greater imbalance between male and female bylines in elite publications than even an attentive feminist such as me would have guessed.

But there is plenty of evidence that we do celebrate work by women that deals with self-creation and toys with the line between autobiography and fiction in the way My Struggle does. Sheila Heti’s 2012 novel How Should a Person Be?, featuring a protagonist named Sheila and the real names of people Heti is close to, received enormous, and mostly positive, critical attention. It is filled with all kinds of “banality”—transcriptions of e-mail exchanges with friends, shopping excursions, talks in diners. One chapter is titled “Sheila Wanders in the Copy Shop.” And publishing has witnessed an international sensation in the Neapolitan novels of Italian author Elena Ferrante, published in the US between 2012 and 2015. The four books that make up this series comprise about 1,700 pages. There are stylistic and other similarities between Knausgaard’s and Ferrante’s works. While Ferrante’s novels read more clearly as fiction, her protagonist is called Elena and shares autobiographical details with the author (as far as can be known, since “Elena Ferrante” is a pseudonym for someone who has so far revealed few details about herself). Both works cover decades of time and employ a conversational, headlong, sometimes breathless style aiming less at elegance than at cumulative emotional effect. Both attend to minutiae, as in this passage from Ferrante’s final Neapolitan book, The Story of the Lost Child. The narrator is staying at a hotel with her lover:

The next day I got up early and shut myself in the bathroom. I took a long shower, I dried my hair carefully, worrying that the hotel hair dryer, which blew violently, would give it the wrong wave.

There is no reason we need to know about the morning’s grooming; the narrator’s hair and its wave do not come up again. The writer merely wants to give us a sense of the day’s unfolding and a hint of the narrator’s anxious need to remain attractive to her lover. While the Neapolitan books contain a higher percentage of dramatic incidents than My Struggle does (murders, countless sexual entanglements, repeated scenes of physical violence), they are primarily filled with a nearly moment-to-moment explication of the narrator’s ever-changing feelings about her lifelong friend Lila, her mother, the various men in her life, and the writers and intellectuals whose ranks she wishes to join. These novels have received ecstastic praise from the most prestigious review outlets in the English-speaking world, far more ecstatic than has My Struggle. We’re also seeing a remarkable level of interest in nonfiction by women about “the everyday”: for example, Rachel Cusk on motherhood and divorce, and Heidi Julavits and Sarah Manguso on their diary-keeping.

We’ll never know if “Carla Olivia Krauss” has been silenced by gender bias. Roiphe probably isn’t completely off base, but some of the “if a woman wrote it we wouldn’t care” commentary is surely rooted in either envy of the freedom Knausgaard has claimed for himself or discomfort with the author’s nakedness. Rejection in love, sexual inadequacy, humiliations by supposed friends, callousness toward a spouse: These are awkward to read about when the author is telling us, This was me. Most writers armor themselves far more—either unproductively, by generating muffled, defensive writing, or productively, by seeding autobiographical emotion in fictional characters and situations, where it is easier to deal with for writer and reader both. Which is why it strikes me as odd that fiction about characters and places and times distant from the author should be seen as less egoistic than autobiographical fiction. Fiction with most of the details made up and autobiographical fiction are just different containers for the same urgent messy human stuff. Neither is morally superior.

When I finished Book Three of My Struggle I felt overwhelmed by the cumulative experience of the first three books. Book Three deals with Knausgaard from the ages of six to thirteen, and the texture of childhood in it, the smells and sounds, the relationship with the outdoors, the wild impulses, sank into me like a vivid dream. Combined with the adult material in Books One and Two, the series so far had given me an astonishingly complete portrait of a human being, in his joys and shames, his loves and hates, his flaws and strengths. The self-portrait seemed not in the least a narcissistic folly but rather a miracle for which I felt an intense gratitude.

Is Karl Ove Knausgaard—the man, the brother and father, the writer—a narcissist? I don’t know him and can’t say. In the novel, KOK is guilty of some selfish and off-putting behavior. I have been guilty of my own versions of such behavior and believe that everyone I know has been, too. Again, this is a man one of whose dearest wishes is that his children will never fear him as he feared his father. But even if he is, or is at times, an egotist, that is a matter for those close to him and not for the literary-critical community to deal with. The narcissism is not in the work. My Struggle is art, and it is a gift.