1.

The mouse before me is dead, its body emptied of organs. Dead but still innervated, so still blinking in this world.

I only harvest from their core—heart, lungs, liver, and the rest—but soon I will have to work with their brains. That organ requires a different skill set. There’s a postdoc in a neighboring lab who will teach me when the time comes. Experiments are still being discussed—I’m waiting for Vasco to give the go-ahead. When that study begins, I’ll spend more time down here and less time in the lab. The days of sitting at my computer, mining data and running algorithms, are behind me. I spend fewer and fewer hours upstairs.

My cell phone rings. It’s face up on the stool next to me, and that phone number—the sight of it—turns me cold. My sister and I have never been close, and after everything we have done to each other, I doubt this will ever change. It’s January. I haven’t spoken to Savo in over a year.

Savo only phones to berate me, and I always answer her calls, knowing full well I’ll be subject to an attack. Her anger is surrogate anger, joined so tightly to our father’s, the borders have blurred, so you never know whose country you’re actually lost in.

I take off my gloves. The phone stops ringing then starts right up again. I turn back to the mouse still pinned to my dissection board and watch it twitch involuntarily, its death still fresh, still clinging to the air. I withdraw the pins from its body. A loud noise reminds me I’m not alone—behind me, Rowan has knocked something heavy to the floor.

It’s always Savo phoning from the apartment—never Sherlock, our father, not since he’d come to the conclusion that I’ve sided with my mother. It’s beneath him now to call me. Whatever messages he has for me come through Savo. She always begins the same.

You think you better than we? You cyant pick up the phone and call my father?

Always her father; never our father.

The lab has broken me in—I don’t so much as raise my voice within its sanitized walls. And yet I still need to feel this outrage. I need to lose control of my blood pressure to be reminded that I am truly my father’s daughter. Sherlock can survive off air and anger alone. He has. He’s cut so many siblings out of his life he verges on being an only child.

Now I rush to answer before Savo hangs up again.

“Hold on, hold on,” I say into the phone, pulling off my gown and stepping into the hall. The animal facility is in the basement of my research building. Service is shoddy. I walk the corridor, toward the locker rooms, to get a stronger signal. Finally her voice is unbroken, and because she has not stopped talking, I pick up with Savo mid-story.

I hear the strain in her voice. I know that things are bad between us—it’s been what? Three years since I’ve been home to Brooklyn, since our mother took off for Florida?—but Savo should’ve called me back when that first toe started to go black. Now our father is going to lose both his legs, and apparently they’ve known it would come to this for some time. That’s Savo—the martyr. It’s fallen on her to look after Sherlock, our mother’s job before her.

“He has sugar,” Savo says, meaning our father is diabetic. “I tell him, ‘You cyant just keep eating whatever you want.’” She mentions black cake and salara—Christmas has just come and gone. Savo can do that thing with her voice, that Guyanese thing of trapping all the anxiety in her upper octaves. She can sound exactly like our mother.

Savo manages an accent though we were both born in Brooklyn, two years apart. Our brother Raja came three years before her, though he’s more a product of the block we grew up on than the household we grew up in.

Savo may be older than me, but it pained me to watch her navigate adolescence. She’s always been sickly, always wandering off at family parties to sleep in some cousin’s bed. In high school, she wore our homemade clothes instead of saving up her money to shop down at The Junction. Her accent, her obedience, the long coolie hair collected in a braid down her back—all of it had secured her favorite-daughter status. There was never any discussion of college when it came to Savo. Our mother, Dowla, taught her how to prepare our father’s favorite dishes: lamb curry, dahl, balanjay, souse.

I hear her say that his legs are neurotic. “Necrotic,” I correct her.

“What?”

“His legs are necrotic, not neurotic.”

Savo is silent. Then she says, “I’m very tired, Suku. You have no idea.” It’s the first time in years anyone has called me Suku, and it comes as a shock. Suku is a nickname—short for Soucouyant—an insult that stuck. At Yale, I go by my last name, my boss’s preference.

“You need to come home,” she says. “I shouldn’t have to tell you this.”

“When’s the surgery?”

“Monday. I go take him.”

“He’s having his legs amputated in three days? And you’re calling me now? Jesus.”

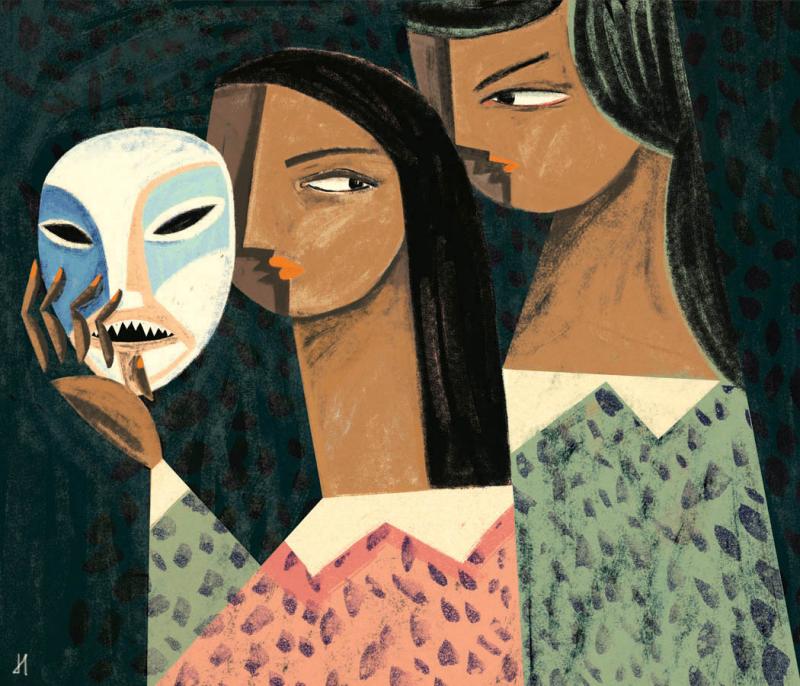

“Let’s not pretend anything,” she says. This is what we’ve become, less sisters than enemies in poor disguise, so that whatever we’re capable of doing to each other, neither of us should act surprised.

A wheelchair won’t make sense in that one-bedroom. Once I saw an amputee scoot down a subway car on bicep strength. Sherlock doesn’t so much as sit on the floor. I try to picture him with prosthetic legs. I imagine a white corridor with handrails along the walls. Someone in scrubs at his side, talking him through his first steps. Sherlock looks up and our eyes meet. He has almost reached me when—

What if such a place is beyond his means? What if prosthetics aren’t even an option? Does she think I have connections through Yale? Does she want me to help them financially? One thought stops me cold: We are poor. Not they, but we. Because the $40K I earn a year gets eaten up in rent, loans, and taxes.

“Poppy wants you home, you hear.” Poppy. I’ve forgotten that name too, our father’s hand-selected moniker, the way he’d forced it on us. So he’s behind this phone call.

Above or below the knee? How much of his legs are they taking? Where will he go after the surgery? Savo doesn’t have any answers. Without prosthetics, work will no longer sustain him. Because how will he get himself to the dry cleaners where he’s been employed as a tailor for the last thirteen years? How could he continue to work—to measure, pin, and hem—seated?

She tells me they’re getting through this one day at a time. For once, she seems desperate. Everything has fallen on her. “You’re his daughter, too,” she says, “Why should I go through this alone?”

“Raja, Dowla—have you gotten a hold of them?” I ask, but I already know the answer.

Last I’d heard, Raja was in Oakland. Passing through—that’s what this cousin had said. Raja’s a drifter—even as a child he was always wandering, first the building, then our block, then later the boroughs, and eventually the country. There was a guy in the building who taught Raja the skills he later made his living from—electrical, plumbing, and dealing (weed mostly).

I have a phone number for our mother, though she made me promise not to pass it on. The last time I saw Dowla I’d flown down to West Palm Beach in a shaky mental state. Or perhaps seeing her had caused my state. I can’t say for certain now which came first.

She met me on the sidewalk outside baggage claim. I saw her before she saw me, and her transformation from the woman who lived in my memory (a seamstress, soft-spoken and pony-tailed, with a safety or bobby pin between her lips, who had always preferred sensible clothes—pants with drawstrings, turtlenecks under sweaters) to the woman I now gazed upon dismantled me.

It had been two years since I’d seen her, and I saw that she wore her hair now in big loose curls, pinned at the crown—dated but elegant—her wide-legged pants and tucked blouse conjuring another era. Her hair, cared for and caramel colored, was lovelier that I’d ever realized. I tried to recall from our recent phone conversations if this change had been evident, but her voice had not betrayed her. She looked at ease in her new attire, everywhere except her eyes, which, as I approached, sought signs of my approval. (Though maybe she sought nothing. Maybe I’m just imagining that. Maybe she stood there coolly, waiting to collect me.) She’d lost weight, and though her face was now gaunt, the circles around her eyes darker, she appeared younger.

She wasn’t alone. The man beside her—this Claude—with his silver hair, artfully styled, and his tailored clothing, black shirt and black pants. His face gave the impression that he bleached his skin—the backs of his hands were much darker. He was thin everywhere except his belly, which protruded, but only a little. Arched eyebrows high on his forehead lent him an arrogant expression, one full of skepticism and disdain. It seemed distinctly Guyanese, this implied emotionality. He had broad lips and small, straight teeth. Stubble brought color to his otherwise pale face.

I was surprised, not just by my mother’s clothes, which were expensive, but by her beauty, which I’d never fully appreciated. And by this man who’d always known it had existed, otherwise why would he have resurfaced, freshly widowed, after all these years? I saw now my mother’s mouth, which turned down at the corners, her collarbone, her boyish hips. The gold bangles I recognized were mixed in with new pairs. She’s a woman capable of morphing into the likeness of the man she’s with. For my father, she was comfort and sensibility, for Claude, grace and sophistication.

Savo, who’s been silent for a while, no doubt sorting through her own recollections—the names Raja and Dowla igniting fires she’d thought otherwise extinguished—speaks now in a quieter tone. “I have no way to reach Raja. And why would I go look for my mother now when she’s the one who left? Let she stay where she is.”

Savo mumbles something else I don’t quite catch, something raw and rich with venom. Whenever I mention our mother, it has this same effect on Savo. She doesn’t understand the need for transformation. Savo had understood Dowla perfectly when she cooked and cleaned and made our clothes, but she doesn’t understand the woman our mother has become, the change that started with a phone call one afternoon from a childhood friend, the brother of a schoolmate she’d known back in Guyana.

“Tell me now,” Savo says, “can you come home?” Until this moment, it hasn’t occurred to me that she’s been asking.

I tell her I’ll be home the following day. We say our goodbyes and hang up. I stand in the hallway until somewhere down the corridor, behind another locked door, a dog stops barking. I make the sign of the cross (Father-Son-Holy-Spirit) and head back toward the animal room.

I stop outside the door. My badge is in my hand, but I can’t bring myself to slide it through the card reader. I’m shaken from Savo’s call.

I don’t want to open up any more mice today.

I don’t want to face what’s on the other side of the door.

The mice are lean with rage. They cannibalize their young.

These mice in particular—my mice—sport their fury. Their mangled genitalia and open fight wounds are by-products of the aggression I helped engineer. They will pop off the surgical table and take the plunge to the floor, disappearing into some crack in the wall as if they knew it would be there. I never exert myself trying to catch the ones that get away. Humidity drives the mouse stench deep into the fabric of my clothing. Nights I walk around my apartment, filling it with my rodent odor.

I spend large portions of the day in the animal facility, the sub-level of our research building—a circular, windowless maze off of which individual rooms house animals according to lab. Mice in our case. Thousands of them, housed seven or eight to a cage—against Yale’s protocol—per Vasco’s orders.

Keep the cage numbers (dollars) down. Harvest often.

The animal room is as loud as the hull of a ship. The mechanical drone of the air and ventilation systems make it difficult to carry on a conversation. The room is filled with the sounds of running water, the reluctant and apologetic groan of temperamental machines. A vent hisses and its warm breath brushes the top of your head. Condensation runs down the gray-painted walls. Beneath your gown—beneath your clothing—beads of sweat swim down to the small of your back.

In the middle of the room are the racks, the double-sided shelving units that house the mouse cages. The racks are connected to air and water supplies. A dozen of them, freestanding like the book stacks in a library, the cages organized according to researcher. By day’s end, the cages are splattered with colored cards. Neon green tells the animal tech to euthanize all the mice within.

There’s an art to putting an animal down. First you must find the sweet spot in the belly, where the needle slides undetected into the cavity. Nail the angle and you won’t hit an organ; miscalculate and the mouse, feeling every millimeter of that needle, will let you know. But you’re good—too good—so you hit the sweet spot every time. And once the ke-tamine is administered, the mouse, now calm and listless, rolls out of your hand, stumbling for a minute before falling still.

You use a piece of Styrofoam as a dissecting board, the lid from a package that was delivered to the lab. Blood has turned it the color of rust. It contains hundreds of holes made from the pins you use to secure the mice, holes that now hold bits of fat, skin, and fur.

You dissect in a ventilated hood—a glass-enclosed surgical table, exhaust running, so a sterile workspace—its window lifted just high enough to admit your hands. You position the mouse on the Styrofoam—a pin through each limb—then make the incision. One cut down the midline, then shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip, and you have your window.

You pin down the flaps of skin. You take a minute and look inside the mouse at its design. There are no shiny cylindrical instruments, no pistons, no arrays. What you have is something far more brilliant and imaginative, something crude and ancient, and that much more difficult to admire.

You lift each organ with your forceps, carefully severing all connective tissue until it’s free, inspect it briefly, then drop it into a formalin-filled jar, the mouse turning its head or blinking while you collect its parts, until too much has been taken, and its life can no longer be sustained, then onto the heap of mouse bodies, where, at last, it ceases to twitch.

I enter the animal room and find Rowan standing in front of the ventilated hood, leaning in toward the glass. When the door clicks shut, he jumps back, startled.

We try not to talk while we’re working. The stench of urine and feces, the dusty taste of wood chips—you don’t want to open your mouth to it. Gowned up, but we still manage to smell like mouse bedding after we’ve emerged and stripped off our layers, long after we’ve returned home.

Savo’s phone call is the first break I’ve had all day. I’d been dissecting for five hours straight. Five hours, thirty-two mice.

All day, Rowan has pretended not to notice my fatigue. Afternoon has turned to evening, and we’re alone in the animal room because the rest of our lab prefers to dissect in the mornings. While I harvest organs, Rowan moves through the racks, binder open against his arm the way a preacher holds his Bible, Rowan consulting genotypes rather than scripture. He scrolls through my log, dragging his finger first down then across the page, landing on a cage number, and slating those mice for harvest.

He’s stacked enough cages next to the hood to keep me in the animal room until lights out, the moment when the timers switch to the night setting. Thursday evening—so happy hours all around New Haven, gatherings arranged throughout the day by our fellow postdocs—and this is how Rowan keeps me to himself. Trapped in the bowels of the medical school, as he likes to say.

Rowan is Jamaican and as familiar to me as my right hand, his brand of possessiveness, forgivable and endearing. He always stays with me until all my harvests are done, an unspoken arrangement we both embrace. He joined the lab three years before me, though I’m closer to a narrative, to moving on. We’ve grown extremely close, and if not for his presence, the mouse work would be unbearable. Nights he doesn’t want to go home and face his mother we get high and watch movies at my place.

“What’s good fam?” he says. I look from his face to the mouse still on my dissection board. No longer blinking, its eyes remain open—dark and curious.

“It’s my father. I need to go to Brooklyn for a few days.”

“Bad bad?”

“He’s having both legs amputated.”

“Damn. Diabetes?” I nod and Rowan shakes his head. “Sorry to hear. How old is he again?”

“Seventy-two.”

“That’s not that old.” He pauses. “Be prepared—he’s gonna make his peace. This is how you’ll get shit back on track. Watch and see.”

Rowan’s words are comforting, but he looks me over intensely. I can see where this is headed. He’ll ask to spend the night. He’ll offer to bring the weed. We’ll watch a movie, and when it’s over I’ll hand him a blanket and pillow before going to bed. Sometime during the night I’ll wake and find him standing in my bedroom, complaining about his back, his pillow under his arm. I’ll turn him away, and after he’s returned to the couch I’ll lie there awake and unsettled. His frustration will find me. It will climb into my bed and press down on my body, in Rowan’s place.

Rowan is in his late thirties. He’s short in stature, compact and muscular. Good hair—he has Indian in him, he likes to remind me—though his hairline has started to recede. A friend sent him a tonic from Haiti, and Rowan applies it to his scalp every morning.

He labors over his appearance; more than anything, he likes to shop. He always returns from New York with shopping bags—designer clothes bought at discount downtown, which he models for me, tags still on, in my Nicoll Street apartment. Garish button-downs and ill-fitting pants, so clearly deserving of their half-off status, though for Rowan, the labels are all that matter. He wears these clothes to the lab, his prized shirts—bright colors, cobalts and crimsons—the top buttons undone to reveal a swirl of chest hair like a hurricane. When he speaks patois—often in front of our European and Japanese colleagues, a seditious affront of lab etiquette—his lips move lewdly over his teeth, eyes squinted as if to see me better, suggesting, always suggesting, what he really wants.

Sometimes when I stare at Rowan long enough, I can find him attractive. Looking only at his eyes (heavy-lidded and deep-set) or his nose (like an anchor planted squarely on his face) or his bottom lip (its pink underbelly exposed), I can see us in bed together. Dissecting his face, I can pocket just the pieces I want to thumb.

I can maintain this heightened awareness for minutes at a time, during which Rowan will seem vulnerable, even slightly erotic. But then I will smell him: his cocoa-butter-hair-tonic-baby-powder scent—all too pedestrian, all too commonplace, calling to mind too sharply his bathroom counter, no one scent mysterious or masculine or glandular—and his features reset, all potential sex appeal lost.

Rowan waits for me to say something more about my father, and when I don’t, he mentions again his mother’s latest brain scan. She has early-onset Alzheimer’s, the PSEN1 mutation, and is living with him in his two-bedroom on York Street. It’s how we were brought up. There’ll be no nursing home, no long-term facility. We both know she’ll die under his roof.

I listen as he goes through the latest findings for a second time. There’s a chance he carries the same mutation, but he won’t get tested even though I could screen him myself.

Work fast and you can nix the anesthesia, he’d explained early on. Work fast and the blood nuh get to you. Work fast, in other words, don’t play by the book. They can’t fuck with we. He’d been written up for the way he handles the mice. Turns out Yale could fuck with you.

This is Vasco’s lab. He’s an MD/Ph.D. and our principal investigator. The boss. He calls us—the postdocs, MDs, nurses, research associates, and grad students—by our last names, a throwback to his med-school days. After I joined the lab, I took out my nose ring and cut off all my hair. Three years and I’ve kept it cropped close to my scalp.

Our lab hunts genes. We map mutations that cause chronic aggression. There’s no simple test for this condition, no diagnostic criteria. Vasco, in fact, coined the term.

I find him at his computer, his focus on the middle of the three giant flatscreens atop his desk. His is a corner office overlooking the hospital, the parking structure. Tenth floor, so the penthouse. There are couches and a round conference table at one end, his desk at the other. His degrees hang on the walls (Harvard, Columbia, and Yale) and his bookshelves are organized, blocks of color representing various volumes of anatomical atlas. There is very little by way of decoration—an orchid, a framed comic strip, and a plasma globe. He looks up and, seeing that I’m empty-handed (without data), he continues typing.

Vasco is anything but pleased with my timing. Three, four days max, I promise. He takes off his glasses and rubs the lenses with a tissue. “I didn’t know you had a father,” he says. I know what he means. We don’t bring our lives to the lab.

Vasco is Lithuanian, in his late fifties, balding, a tall lanky man, with pale skin and what my mother would call piano fingers. He clears his throat as he walks through the lab, a way of announcing his approach. There’s an unspoken rule: He should never be the first to arrive or the last to leave. I’ve become a recent favorite, and now in the slow, tempered manner in which Vasco cleans his glasses, I feel myself sink back to my former status. It took three years, but I’d conquered his moodiness with my experiments, and now this trip home will put all that at risk.

“I suppose Rowan will be looking after your mice while you’re away.” Vasco sees everything, so he knows that Rowan and I are tight. Not long ago, it was decided that Rowan would be given a free ride on my first-author paper, so he’d have a new publication and a better shot at funding. After the paper came out, I didn’t speak to Rowan for two weeks. Vasco does this with his scientists. He can either protect us from one another or throw us into the ring, whatever suits his mood. I always manage to hold my own against Rowan. Because though he has a straightforward project, nothing he touches seems to work, not even the most basic protocol. He’d also sat for days outside Vasco’s office to vie for a spot in the lab, but what can you ever tell about a person until he’s tested?

“Actually, I had someone else in mind,” I say. “Takuro.”

“Takuro-san.” Vasco says this with a smile, understanding that I know what he thinks of Rowan. I feel reassured, reassured and nervous. Vasco is pleased.

2.

Midwood is a one-way street. All along it cars are double-parked. No one bothers with hazards anymore. No one is leaning on a horn, waiting to be let out. Midday and the street is quiet.

I slip my hatchback between two parked cars, my eyes on the inches between my side-view mirror and another’s. There are no spots, no signs of anyone leaving. Tires are packed with sand and salt, windshields a smear of mud. The street has a dirty sheen. Week-old snow piles around lampposts and along curbs, porous and knobby. On the radio, there’s talk of a storm. Alternate-side-of-the-street parking had been suspended all throughout Brooklyn and the other boroughs. A ceiling of clouds presses down, pigeon-gray and serious.

The brownstones aren’t as stately as I remember. Now I see their cement-slab yards, their wrought-iron security measures. Their chipped paint and rusted metal. Their neglected charm. Air-conditioning units jut out second- and third-story windows. A new door stands out from the rest. I see the same planters huddled along stoops and sidewalks (someone’s idea of beautification) and rows of still-anemic saplings.

Midwood is a break in the nickel-and-dime hustle of the surrounding streets. Up ahead, Flatbush Avenue is dense with maroon and blue awnings, with signs that shout 24-hour, halal, roti, wic, and human hair. Flatbush is loud with city-bus flatulence. Midwood is quiet and tree-lined, a remnant of a neighborhood that no longer exists. Blocks away, storefronts crowd at the feet of old architecture, a patina on the past.

At the crossroads of Midwood and Flatbush is my old apartment building, the only one on the block. Six stories high, and just as wide. The recessed entrance gives the building its U-shape. We call the space out front the courtyard. In the summer, it attracts young men with forties and old timers with folding chairs. The facade boasts a green awning, arches, and gold pillars, the promise of dignity within. The rest of the building is fire escape and brick.

In the last couple of years I lived there, the intercom didn’t work. We would stick pennies in the door when someone was coming over to visit. Until one winter when a man, urine-soaked and blanket-heavy, camped out in the stairwell, and everyone whispered in the hallways about security.

I circle the block. On Flatbush, there are new businesses I don’t recognize—a Dominican salon, a check-cashing place, another laundromat.

Already, I’ve fielded two calls from the lab, both from Rowan. On the first, he informed me that he’d be looking after my mice, that Takuro had to make a deadline. There was a hardness to his voice I couldn’t crack with a joke. I tried not to read into it. Maybe he’s mad because I didn’t want company last night. Maybe he’s pissed about the extra mouse work. On the second call, he double-checked cage numbers and confirmed my instructions for pathology, business as usual.

I turn once again onto Midwood, hoping a spot has opened up. Still nothing. I pull over just shy of the building and wait. One of the guys playing Cee Lo, I recognize him from high school. The crowd I used to hang with, most of them still live in the same old apartments with their parents, a few take night classes at Brooklyn College. Some of them, I don’t know where they ended up. Queens, maybe.

I’m staring at the old building when Sherlock appears. He steps out of the courtyard and onto the sidewalk, and I see he has a cane, a metal number with a four-pronged base. He has on the varsity jacket with the ivory elbow patches that the Koreans let him take home from the unclaimed rack. The aviators he found on the bus, left behind at rush hour. He has on jeans (dungarees, he likes to say), starched stiff and creased down the front. His scarf—long and white—I don’t recognize.

He moves now by sliding each foot forward, looking up every few steps then back down at his feet, like he’s working out a calculation in his head. I think only of black ice, of him falling.

He stops and leans on his cane, one shoulder pitched higher than the other, and looks down the street in my direction. I watch him, wondering what he’s doing out in the cold, before I realize he’s waiting for me.

I pull my car forward and roll down the window, and he bends at the waist (it must pain him to do so) to see my face before stepping off the curb.

“I thought as much that was you,” he says.

“I’m waiting for a spot to open up.”

“I’m getting in. I need to sit down.”

He struggles with the cane, and I help him get it between the seats and into the back. He’s lost weight—I can see it in his eyes and ears, which now seem too big for his face. He smells like the apartment, like incense and cooked food, but there’s something else. It takes a minute, but then I recognize the face cream my mother used to use.

I ready myself for whatever onslaught is coming. Daughters are supposed to serve and obey. Daughters don’t have free will. Having daughters means you have wives, plural. Years ago, a niece on his side was put on suicide watch after her father passed away. She collapsed at the funeral, and when she came to, she begged God to take her to her father. Sherlock tells this story like her behavior was the most natural thing in the world. Like it was to be expected.

I turn and face him, my shoulder touching the driver-side door. I look into Sherlock’s eyes and see none of the nastiness I’ve been anticipating. His eyebrows, plucked thin and clean, are smooth, dark arches.

“Your hair,” he says, “it suits you.”

I touch my head and realize my hand is shaking. “It’s not too short?”

“Not at all. You look like my mudda, your grandmudda.” He looks awful.

“Listen, I had no idea that—”

He puts up a hand and stops me. “This is God’s plan for me. For we. I pray for you, Savo, and Raja every night, every night I pray for Father God to watch over you, even if you don’t do the same.”

But I do. I pray every day, once upon waking and once before bed. I want to tell him this, but I don’t interrupt.

He says he needs me to drive him somewhere. He points and I make a left on Flatbush.

“Where are we going?”

“Sybil’s. I picking up bread and dahl pouri from—what she name? Girly. You want curry tonight?”

I tell him yes, knowing it’s already made.

There’s a spot outside the restaurant, but he asks me to stay in the car while he goes in. It’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen, my father walking on dead limbs. Inside he bypasses the line, and Girly comes around from behind the take-out counter to hug him. She calls him Uncle, a term of respect, because her father and my father have been friends since Guyana. Instead of heading into the kitchen, they stay out front in full view of the car. I see him point to me, and they continue to talk, Girly smiling and looking back and forth between the car and my father’s face, a sure sign they’re talking about me. If I’d gone in, he wouldn’t have been able to speak openly and I never would’ve seen him like this. Like this, he can talk at length about Yale. Like this, he can invent whatever details he wants, say med school instead of grad school, leave out the last three years. Like this, he can brag.

One day, when I was in high school, Sherlock came home and asked us to start calling him Poppy. On the bus he’d overheard some woman calling her man Papí, and he’d liked it, or more specifically, he’d liked her. He started calling himself Poppy, signing it on the notes he left us.

Savo, of course, acquiesced and made the switch at once. She said Poppy over and over. Here are your slippers, Poppy. What can I get for you, Poppy? Can I take your plate, Poppy? And the more it became obvious that I wouldn’t say it—would never say it—the more frequently Savo addressed him by this name, each time with greater authority.

And while Savo’s confidence grew, it seemed my father was tortured, overcome by the affection of one daughter and mocked by the resistance of the other. Over time, almost imperceptibly, he changed his attitude toward me. He started looking at me critically whenever I returned to the apartment. He started calling me Suku.

At night, the four of us—Sherlock, Dowla, Savo, and myself—would sleep in the bed, Raja on the couch. You’re putting on weight, Sherlock said, one night while we were all lying there in the dark. You have too much ass, you hear. After, whenever he plated our food, he’d cut my servings in half.

The old building smells the same as I remember, like the air hasn’t changed—two parts bank vault, one part take-out kitchen. My father hooks onto my arm, and I take his cane and bags. The elevator door closes reluctantly, and it takes a minute before the compartment jerks to life.

He leans all of his weight against me, though he could’ve just as easily leaned elsewhere. He uses me for support, and I wrap my arm around him, as if to say, it could’ve always been like this.

I start thinking of ways to come home on the weekends. I’ll stay later during the week. I’ll work something out with Vasco.Among the graffiti that covers the elevator walls, someone has scrawled sometimes the queen is a king.

Sherlock bangs on our door instead of using his keys. I hear Savo on the other side working the locks. When the door opens, Sherlock rushes past her and falls into a chair. “Where my slippers dey?”

I lock us in, then hand Savo the bags, trying not to stare at my sister’s face. She’s still thin (delicate now, rather than sickly—a change in my perception, not her appearance). Dark circles around her eyes bring out something foreign in her features, features she complements with a nose ring and tunic. Box-dyed and blue-black, her hair falls in loose waves to the small of her back. I think of the guys outside playing Cee Lo and wonder if she’s still a virgin.

“So you reach,” she says, staring at my hair.

The apartment is warm with oven heat. I take off my jacket, hang it on the back of a chair, and trade my boots for a pair of slippers. The apartment has more West Indian craziness than I recall. Savo’s doing. Elephant statues, tails turned toward the door. A cluster of devotional candles in the corner. There’s a picture of the Virgin Mary over the television, Saint Christopher over the kitchenette. They have lovebirds now. I hear the flapping of wings, like the rustling of newspaper, before I see the yellow cage in the corner. Every inch of free space is now occupied by furniture—side tables and orphaned chairs. The air is dense with lemon-scented chemicals—Savo cleans top to bottom every day.

I’m struck by my mother’s absence. The apartment is without her sense of propriety. Album covers—bikinied women and steel drums—are propped up, on display. Mini-bar bottles of liquor are arranged decoratively on tables like figurines. Photographs are scotch-taped to the walls, yellowed images from the sixties over the couch.

I glance down the hallway into the bedroom and see the armoire, shoeboxes stacked on top. In those boxes is our inheritance—Savo’s, Raja’s, and mine. Photographs, Indian gold, and savings bonds.

I walk into the bedroom, feeling at once like a stranger and the prodigal child. My place in the bed was always between Savo and my father. I tell myself I won’t sleep with them tonight, not now, not between them. I’ll take a blanket to the floor, even if it threatens the peace.

Rowan calls before dinner. Vasco asked him to harvest brains—he wants him to run qPCR on my mice. Dissections all day, now extraction and synthesis tonight. Someone in the neighboring lab is helping him. Jitesh—someone good. I’m worried now about my project, my ownership of it. If it was in Rowan’s hands alone, I wouldn’t be concerned, but he has help. Jitesh already has the probes.

“It can’t wait until I’m back?”

“Nah. Vasco’s way too hyped about it.” I know Rowan well enough to tell he’s holding something back. He says, “J. Z.’s paper was published online today, so we have to move.” J. Z., a competitor —I should’ve checked the publications before I left.

“What’s Vasco so hyped about? What does he want you to look at?”

Rowan pauses, and I can tell he’s covering the phone to confer with someone. I hear a muffled exchange before he comes back with a short list of transcripts. I see where this is headed, and if Vasco is correct, the implications could be huge. Already, my head is spinning, making connections between pathways.

“And why can’t this wait again?”

More sidebar. There’s only one person he can be talking to. I watch as Savo opens a window and throws a trash bag down to the alley below. It could be my gut dropping those five stories.

“Hello?”

Finally Rowan comes back on. “You paranoid or something? It’s not like he’s handing me your project. I’m doing you a favor.”

“Don’t do me any favors.”

“What can I tell you? Miss a day, miss the boat.” So this is my punishment. I have to know.

“Remind me,” I say, “what’s that you’ve started calling Vasco?“

“What?”

“What’s that name you’ve been calling him?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Jancro? Was that it?” No response. “Yeah, that was it. What’s that mean again? Lowlife?”

More silence. That’s all I need to hear.

Savo knew enough about the guys I was messing with to torment me. Seniors when I was only a freshman. She pulled Soucouyant out of the ether, a new name for my new persona. Sensing that it would somehow cause a disturbance—the nature of which not even Savo could have guessed—she repeated it in low tones, taunting me at first, a private matter between sisters. The first time she said it, I was too scared to respond, too afraid she’d push me on its meaning. For once, she understood something I didn’t.

It took some time, but one evening Savo’s word finally registered in the apartment and found its way to Sherlock. He didn’t say anything right away, just studied the end of his cigarette as if it were a joint.

I waited, understanding that when he spoke next he would be choosing one daughter over the other. I can still remember how he looked sitting in that armchair. Wearing just his trousers and his gold (a bangle, two rings, and a crucifix). His legs crossed, his pant leg hiked, I saw a window of skin, a downy patch of delicate-looking ankle.

Where you learn that word? I ain’t heard that since back home. Gal, he said, addressing Savo, you sure you born here?

He was amused. Savo had done well to discover this word. Suddenly Sherlock was animated, as I’d seen him only when he was in heated debate, politicking with his brothers. With a single word, Savo had transported him back to Guyana. I should have guessed—conduits to the past were currency. Using the tip of his cigarette to light another, he reminisced about women he had known, and our mother left the stove and went in the other room. And while I didn’t fully grasp what these women had to do with me, I felt a certain humiliation. One woman he described ran a beer garden, went topless at the seawall, and could drink her weight in rum.

After a while it didn’t matter that anyone else was in the room with him, or that this apartment was in Brooklyn, or that Brooklyn was in the States, because for the time being he was back home, young and schooled in the ways that mattered. Finally, when his excitement had subsided, it was no longer clear that Savo had unearthed that word, for he now possessed it entirely.

Soucouyant. He started calling me this at once. Savo had resurrected this word for him. She’d placed it in the palm of his hand and made his fingers a fist around it. Now you can wield it, too. Soucouyant turned to Suku. Our mother, her brothers call her Pussycat, and from a woman like that what could I expect?

I don’t know whether or not Savo, if she could, would take it all back. Not knowing has ruined us.

I had to ask our upstairs neighbor, a Trinidadian woman, the meaning of my new name, and she described a changeling, a vampire, traveling through the night under the guise of fire, ravenous for blood. At dawn, she would resume her original form—she was both human and evil.

They’s pure trouble.

I saw myself in that neighbor’s description. I saw a duplicitous woman, desirous and ambitious. Starving, reaching. Free.

Savo is trying to get my attention.

“Suku?” She waves her fork in front of my face.

Sherlock looks up. “Suku. I’d almost forgotten.” He’s been hunched over his plate, his fingertips now yellow with curry and pointed toward the ceiling like a surgeon entering the operating room. Now he leans back in his chair and stretches.

“You know what we called Savo when she was a baby?” I shake my head. “Watch little laugh,” and he cocks his chin in Savo’s direction so I’ll be ready for her reaction. “Katahar.” He pauses so I can picture the prickly fruit. “Katahar—because her face was full of bumps. When she born, she was an ugly thing.” He looks right at me with eyes so milky they’re almost blue. His mouth opens into a distracted smile as he looks back in time.

Savo’s chin drops to her chest and she sets down her fork. She closes her eyes, and I see now that things have changed between them. I reach out and touch her arm, wanting to tell her—I know what his words are doing inside of you right at this moment, mixed up in your blood, bathing your heart. And she seems to want to say something too, though she must change her mind.

“Savo,” he says, “clear the dishes.” Then to me: “Let me show you something.” Sherlock pushes back his chair and rolls up a pant leg. With his hand, he indicates that I should come around, and I have to get down on my knees to satisfy him. The smell hits me first—organic and septic—the smell a dead animal gives off in raw sun. He is decomposing, my father. God is claiming him piece by piece. And though I see it every day, it shocks me still—the savage methods of the body, its vulgar processes.

Below the knee, the leg is shades of red and black, wounds glossy with pus. There is a sore along his calf that tears me to pieces—a crater of exposed muscle, ringed in yellow, a furious red at the core, like a cross section of the sun.

He shows me the other leg, then I’m back in my chair. Savo stands at the kitchen sink, staring over her shoulder at Sherlock. He meets her gaze and words pass between them—a conversation I’m not privy to.

“When you’re ready,” he says, “there’s a blow-up bed for you.” His voice is soft, like a hand on the nape of my neck, and though this is what I wanted—not to lie with them—I fight back an incomprehensible swell of disappointment.

“You didn’t have to do that,” I say, but he doesn’t hear me. Savo rejoins us at the table, and I look back and forth between their faces, feeling once again like the baby of the family.

“They go take my legs,” he says. “What good am I then?”

“God has a plan for you. You said so yourself.”

“He does. I prayed, and now you’re here.” In her chair, Savo begins to cry.

He says, I need you now. He says, This nurse brought it over. It’s in the fridge, Savo will show you. He says, I just need you to put it in my veins.

As I replay his words, shuffle them and let them resettle, every molecule in the air gets pushed to the corners as a hundred dead relatives crowd into the room.

“What’s he talking about?” I say to Savo.

She stands and goes to the refrigerator. I try to look in her eyes and read her expression as she places a syringe and vial in front of me.

“It’s a cocktail,” she says. “It’ll put him right to sleep.”

I push my chair away from the table. “You want me to end your life?”

“What choice I have, eh? Live like some leper? No woman, no manhood.” He’s angry now. “What I’s ever ask of you?”

“You can’t be serious.” He is.

“Just because they’re amputating your legs doesn’t mean you can’t go on living.”

“Who will want me?” he says. “Who will fuck a man with no legs?”

This is my father. The future that stretches before him is black ice and dark highway. Half a body equals half a life—simple math for a simple man. What is he without his prowess? Without his stride, his domineering stance? Without women to serve him—without women to service?

His legs are dying, and with them my fear of him. I look at Savo. She’s fed up and exhausted. For once, she doesn’t care whom he favors. Isn’t it true that our father is already losing his power? There are ways for him to go forward and make a new life, but he isn’t a man capable of new thinking. The way he’d grown up—crammed, four siblings (four bodies) to a mattress at night—is the way he’d forced us to lie with him. There’s no part of me that believes he’s capable of evolving, capable of an evolved thought. In his mind, he is already dead.

I look to Savo. His true daughter—she should be the one. “You do it,” I say.

“We can’t,” she says. “We’re Catholic. It’s a mortal sin.”

My head has been severed. They’ve gutted me. I feel my phone vibrate in my pocket. Vasco. I stare at my hands and something worse than neglect buries me alive.

Let the scientist do it, they must have said, lying together in bed at night. Let her commit the greatest of sins. She is the thinker, no beliefs—no soul—weighing her down. Fools, she must think us. Well, let’s put her to the test.

I hear Sherlock say, “You don’t pray, you don’t go to church. You educated, not like we here. You don’t believe the same as we.”

“I can’t do it.” But until this moment, I have no idea what I’m made of.

Savo says, “Please.” She says, “Do it for me.”

I see them as they are—a couple in dire need of a divorce. Small beads of condensation run down the glass vial. I can walk out; it would be so easy. I can just get up and leave. But the truth keeps me seated: They didn’t want me in this life, and now they don’t want me in Eternity.

I’ve held countless hearts in my hand. I’ve turned them over in my palm. A heart can pulse for an hour outside the body. It’s a meaty, sinewy thing, striated and resilient.

It cannot break.