To say he wasn’t having fun would be imprecise. It was pleasant, what they were doing: drinking wine, making mean jokes about popular podcasts, listening to songs from artists that had once seemed essential but now seemed absurd. If he could spend a vacation doing anything, these are the activities he would choose. But tonight he was only pretending to be happy, and he feared the others could tell he wasn’t listening to the conversation, even when he himself was talking. There were other things on his mind. He didn’t need friends right now. He got up from the rocking chair and disappeared through the screen door that led to the beach. He could hear his wife asking why he was going out into the rain, but he didn’t look back and behaved as if he’d heard nothing at all.

The drizzle was negligible, almost a mist. It would be an hour before it rained for real. He walked without shoes on the impossibly long wooden dock, over the dunes and out toward the water. At first, he could still hear the music from the living room mixed with the voices of the various couples, particularly the donkey laugh of his old pal Roger. By the time he reached the middle of the dock, Roger’s laugh was the only sound he could decipher. When he reached the dock’s end, he could hear nothing except the ocean. He was finally alone.

“You should be happy to have this problem,” he kept telling himself, as if it were possible to change your feelings by criticizing your conscience. He’d received the offer Friday afternoon, just as he and Veronica were catching the ferry to Atlantique. He sheepishly passed the phone to his wife so that she could read the email. “That’s amazing,” she said without inflection. “What are you going to do?” He stared straight ahead, like a cow. “Let me rephrase the question,” his wife said. “What are you going to do, besides not talk about it?”

He spent the next thirty hours incessantly balancing two thoughts at the same time. The first thought would change. The second thought did not. When he was scrubbing the grill, he thought about the cleanliness of the grill, but also about his problem. When he threw a Frisbee on the beach, he thought about the velocity of the wind and the accuracy of his toss, but also about his problem. In the shower, he thought about his problem while searching for the shampoo. He never relaxed. It never went away. He took an afternoon nap and woke up exhausted. The complexities of the conundrum were so straightforward. There was no way to simplify the decision. If he accepted the offer, he would make more money. But it wouldn’t be life-changing money, because that had already happened in his twenties and money can only change your life once. If he accepted the offer, he would travel constantly, often to exotic places. But traveling is only exciting if you’re single. What’s the upside of meeting interesting people if you’re already married? His preference was to exclusively encounter people who were boring, and those people could be found in New York. If he accepted the offer, the work would be challenging and (potentially) satisfying. It would move him into a rarefied tier of his already-rarefied profession. But wasn’t his current mediocrity challenging enough? Wasn’t his life already (potentially) satisfying? He was about to turn thirty-three. The number of years he still had to work was roughly equivalent to the number of years he’d been alive. That felt like a prison sentence. Maybe if he took the offer, he could bank the money and retire at forty-five. But that would never happen. The kind of guy who took this type of offer always worked until he died, and he would become one of those guys. He probably was one of those guys already, which is why the offer was made. Besides, what good would it do to retire? He couldn’t even enjoy a vacation. One fortuitous problem was all it took to ruin everything.

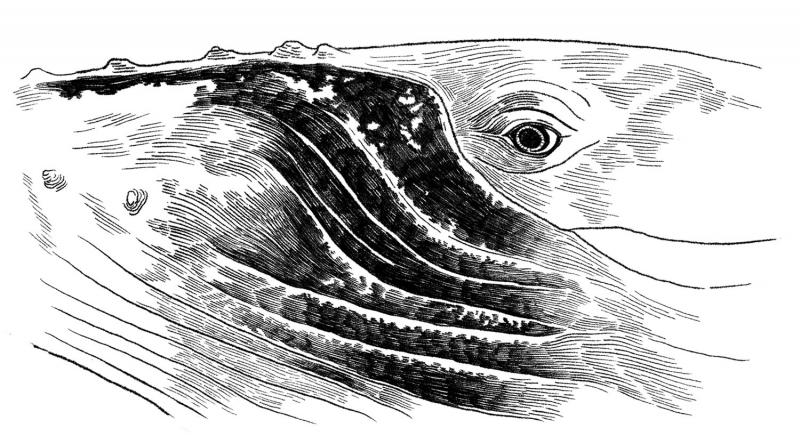

He stared at the black ocean and felt like a child. Why was he looking at something he could barely see? All that was visible was the horizon, but just barely. The waves were so dark. They were not even shapes. He could hear them more than he could see them. Every so often, a crooked bolt of lightning would slash across the sky and everything would be illuminated for half a second. For an instant, he’d see the entire beach, no differently than if it were noon. But then the bolt would vanish and the landscape would cut back to blackness, and all that remained discernible was the vague difference between the water and the sky. He decided to go back to the house, embarrassed by his abrupt departure. It was getting colder and there was nothing to see. He started fabricating an excuse to explain why he had walked out of the house and into the darkness. And then it happened. The horizon exploded. The stasis was shattered by something huge and fast and far away. A whale. A humpback whale, breaching the surface before falling back into the sea. He’d never before seen a whale that wasn’t on TV. He’d never considered the possibility of seeing a whale in these waters, or even the prospect of an invisible whale lurking beneath the surface. Yet there it was. He’d been staring into nothingness for no valid reason, and then he’d seen the unmistakable silhouette of a thirty-three-ton mammal pitching itself out of the ocean and into the air. This had really happened, and it had happened to him. And then, twenty seconds later, it happened again. The same whale jumped forty feet above the surface, arching its spine and twisting its torso.

Except this time, the whale was struck by lightning.

The bolt struck the beast at the apex of its breach. It appeared to freeze in space, suspended in midair like an aquatic Wile E. Coyote before dropping like an anvil. It fell into the abyss the way ducks fall from the sky when blasted with a shotgun. There was no sound to accompany the electrocution. It was too far away. All he heard was the waves hitting the shore in front of him. But he knew what he saw. This had really happened, and it had happened to him.

He scanned the horizon for another two minutes, wondering if he would somehow see the whale alive. A creature that size might be able to absorb a heavy electrical jolt. Then again, whales live in the water, which is not the ideal venue for surviving thirty thousand amps of energy. Was it dead? It was probably dead. It had to be dead. It was dead.

The drizzle started to pick up, as did the wind. He turned and walked back to the house like a blind man late for work, guiding himself along the dock’s rail. The darkness had gotten thicker, bordering on scary. He only knew he was close when he heard Roger’s donkey laugh. He had to get back to Roger. The screen door he’d used to exit was now latched and locked, so he jogged around to the front of the house and barged though the main entrance.

“Veronica,” he said as he pushed open the door. He must have yelled her name with an alarming tone, because his wife jumped up from the couch and ran into the kitchen. “Chad? Are you okay?” she asked. “Is somebody out there?”

“Let’s go up to the bedroom,” he said. “We need to talk.”

Back in the living room, the other three couples fell silent. They turned off the music, then quickly turned it back on in order to seem casual. Chad and Veronica moved to the upstairs room they always shared and closed the door. He sat on the bed. She continued to stand. They both looked worried for reasons neither could explain.

“What’s happening?” she asked. “They’re all going to think we’re fighting. Are we fighting?”

“They can think what they want,” said Chad. “But I wanted to tell you that I’m declining the offer.”

“Good,” said Veronica. “Great. I’m relieved. But are you sure you don’t want it? You can absolutely pursue it, if that’s what you want. I will support whatever you want.”

“We should have kids,” said Chad.

“We should?” They’d never discussed this possibility before.

“We should have three or four kids,” said Chad. “Maybe five or six. And I think I want to do something different with my life. There are other things I can do. If we sold our apartment and moved out of Manhattan, we’d have plenty of money. We’d be rich in Denver—or Detroit. There are lots of things I’m good at. Maybe I could be a greenkeeper at a golf course. I like mowing grass.”

“We are not leaving New York,” she said. “What are you talking about? Where would we move? Fucking Detroit? What about our friends?”

“I don’t care,” he said. “Maybe we need to get past that.”

“We need to get past having friends? What happened out there? How much did you drink tonight? What’s next? Are you going to start going to church?”

Chad kept his eyes on the carpet. He noticed how dated it was. He could almost see the seventies. He’d never noticed that before. He stalled for time and tried to construct an explanation that would sound equitable to his wife. Instead, he just told the truth.

“My life has peaked,” he said. “It’s time to start a new life. Maybe there can be another peak.”

Veronica tried to stop herself from rolling her eyes. She failed. Veronica was the kind of woman who always wished her husband talked about his feelings more than he did. Now it was actually happening, and she was surprised by how annoying it was. Why was this happening tonight? It had been a wonderful weekend, up until now. “Go to bed,” she said. “I’m going back to the party. You go to sleep. Sleep it off.”

“Can you please send Roger up here? I need to talk to Roger,” said Chad. His own voice reminded him of a little boy. Veronica rolled her eyes again and tromped down the stairs, her steps loud enough to signal disgust. The bedroom door was wide open. Chad could hear voices murmuring from the living room, and then muffled (and perhaps condescending) laughter. Soon after, he heard a large mammal bounding up the stairs, two steps at a time. Roger ducked his head to slip under the top of the bedroom doorframe and sat on top of an oak desk by the closet. They both wordlessly worried the desk might collapse, but it kept its integrity.

“Veronica says you’re having a nervous breakdown,” said Roger, smiling the way he always smiled at his own jokes. “I hope she’s right.”

“Do you remember the first weekend we came out here?” asked Chad.

“Yes,” said Roger. “Bush was president.”

“Do you remember a conversation we had on the deck that weekend? It was super late, maybe two in the morning. There were a bunch of us. We found that VHS tape of Working Girl and watched it on the black-and-white in the basement? You were still dating that girl with the big feet? We didn’t know the grill needed propane, so we just ate corn on the cob for three straight days? Do you remember any of that?”

“I remember all of it, except for the conversation on the deck.”

“It wasn’t really a conversation. It was more like a lecture,” said Chad. “You were out of your mind on mushrooms. You were lecturing everyone about the greatest hypothetical moment any person could potentially experience.”

“That doesn’t sound like me at all,” said Roger. “Although I’m guessing I said it would have been if Michael Jackson had recorded a duet with Prince that was produced by Nile Rodgers.”

“No, not that. Although I think that was maybe mentioned.”

“Was it about eating a bucket of chicken on the summit of K2?”

“No, that was a different night. That was when you were listing all the things that money can’t buy.”

“Was it about riding on the back of a Kodiak bear through a forest fire?”

“No.”

“Was it about the possibility of seeing a whale struck by lightning?”

Chad confirmed the query with his eyes.

“Jesus fuck,” said Roger. “There’s no way that actually happened. Did that actually happen? Is that what you saw out there? Are there whales around here? Since when are whales something we can see from the dock? What did it look like?”

Chad stared at his shoes and held his hands above his head. “It looked like what it was.”

“You know, people have done the math on this,” said Roger. “You multiply the number of whales on Earth by the percentage of time whales come to the surface against the odds of lightning striking the water. Something like that. Calculus is involved. I can’t remember the exact answer. It’s like four point eight or four point nine—five whales a year, basically. Five whales a year get struck by lightning. If you believe the math, which I don’t.”

Chad listened to Roger, his favorite friend. Six-foot-eight. Three hundred and forty pounds. Never played sports. Never been in a fight. Never depressed. Never exactly correct.

“I need to change everything,” said Chad.

“I agree,” said Roger. “There’s no going back from this.”

“I’m not joking.”

“Neither am I.”

Chad reclined onto his back, his legs still dangling over the bed’s edge. The mattress was itchy and uncomfortable. It was like lying on a bale of straw. He’d slept on this bed at least three dozen times, but he’d never noticed this before. He’d never noticed it wasn’t comfortable.

“Why do you think you said that?” Chad asked. “All those years ago. I mean, you were joking. I know you were joking. You say idiotic things all the time. But still. Why did you say the greatest thing that could happen to anyone was to see a whale get struck by lightning? Why would you possibly say that, of all possible things to say? What was your point?”

Roger offered no response. He didn’t need to provide a point. His point had been made.

“I’m going downstairs,” said Roger. “Do you want me to send Veronica back up here?”

“Yes,” said Chad. “We need to get started.”