One day, I drove the hundred miles east to visit T at Ironwood and was denied visitation. The clerk told me there was no record of my request. Never mind that I had been visiting my son there every Saturday for five years. The man made like he’d never seen me before in his life. I am six foot three with an eyepatch and hips like holstered guns. I am hard to miss. But back on the highway in my half-dead car, I had to admit that lately my presence had failed to register. I was sixty-two and over the hill that blocks the roving eyes of men, which was fine by me, but I was disturbed by more recent developments. The week before, a car had nearly run me down in the parking lot while I was collecting carts, and a grubby teen tried to stuff a frozen dinner down his pants right in front of me while I was restocking in aisle four. I had my employee badge on and everything: Hello, I’m PATTY. How can I help you?

Outside, the sky scrolled by, clear, blue, cloudless. I tightened my hands on the wheel and watched the gas meter go down. My life was a crime with no witnesses. Who could say it had even happened? T had another twenty years. We were supposed to have watched each other, me to watch him grow, him to watch me grow old and tell me when I had food in my teeth. “Good,” I’d said, when he got in for culinary arts at College of the Desert. “You can keep me in chicken dinners when my chicken is cooked.”

“Goose, Ma,” he’d said, but in the end, it was neither. He went to court a week before his first semester. When the verdict came, I literally cried my eye out. I have not cried since, but it is possible that sitting on the couch that evening I heaved a couple of dry sobs. Then I put on the box. It was late when I muted the TV to silence a long list of side effects and heard the front door open. It’s a small house, one of those prefab jobs that arrives in two bits on the back of a truck. I stood and went to the doorway of the den to peer out into the front room. There was a man standing just inside the entrance. His face was rubbery and white in the gloom, featureless as string cheese. I saw him but he did not see me. The way he paused, I thought for a second he’d made an innocent mistake. Then the man swiped his hand in the bowl on the counter where I keep loose change and a chill unzipped my spine.

“Hey,” I said. His eyes moved fast in his bald head. He looked surprised. I remembered it was street cleaning and my car was parked up the block getting crapped on by the jacaranda. From outside, it didn’t look like anyone was home. My thoughts leapt to different outcomes. He’s going to run, he’s going to attack me, he’s going to piss in all the closets and leave. Instead, he just looked at me. A long look: measuring, taking in details. It felt kind of amazing, like lost flesh growing back over my bones. Briefly, I wanted to hug him. “Get out of my house,” I said. He didn’t move. Everything waited: the curtains, the chipped credenza, the chairs. He smiled.

“Phone,” he said. “Wallet.” He took a step my way.

“Hey,” I said again.

“Shut up,” he said. His right hand curled at his side. “We do this quick. You got a watch?” I put my phone and my wallet on the floor in front of me, showed him my bare hands. He went from room to room. He emptied the medicine cabinet and took a bottle of scotch as well as the laundry detergent from under the sink. He kicked at the closet, tugged some clothes off their hangers. He took the knife kit I’d bought T when he got into school. Brand new, if old, in a red canvas case. He took what he wanted and left. At the door, he pointed at himself. “I was never here,” he said. He turned the same finger on me. “And neither were you.”

Six weeks after the incident I was scrawny as a scarecrow and on thin ice at work. I got myself in on time and ticked like an automaton at the scanner, but I wound down quick if nothing was placed directly in my line of sight. I ran out of singles and started saddling customers with palmfuls of dirty change. At work, there is always work to do, suggested my manager Len. That is why it is so called. There is restocking and inventory and wiping up the mess in aisle thirteen, there is How Can I Help You? I had lost my drive, Len suggested. I needed more initiative, said Chet, the child who’d taken my promotion. The two men looked at each other and nodded.

At my lunch break, I slunk out to the park for a smoke. The park is more of a parking lot, actually, a stretch of cracked asphalt, dirt, and dandelions spilled out behind the store. I used to let T play there at the end of my Saturday shift when Mrs. Epps dropped him early for a hand of poker. You might call it irresponsible to leave a child of five or six unattended in an empty lot, but I swear I never took my eye off the boy even a minute at those times. I would be scanning some slob’s hot sauce, ham, or corn snack, and I swear to you one eye was inward the whole time, watching him dart and duck around on the lot. It was this eye I lost when he went inside, the eye that looked in.

That afternoon, to my surprise, I saw about a dozen kids moving in slow motion at the other end of the park. They were doing a kind of dance, all in sync, only so slow they seemed hardly to be moving at all. It was graceful and eerie. I shuffled over to get a better look.

“Yo,” I said, nodding at the coach-type guy standing to one side. He startled and crossed his arms above his belly.

“Didn’t see you there,” he said. “Can I help you?”

“What is this?”

“Tai chi,” coach said.

“Patty,” I said automatically, extending my hand. He eyed the smoke smoking between my index and middle fingers.

“It’s martial arts,” he said. “Kind of self-defense.”

I perked up a little at that. “Why’s it so slow?”

“Go slow and feel the flow,” he said. “You move too fast you miss the details of your performance. Instead, we concentrate and coordinate, working our way up to powerful, continuous movement.” He glanced back at the kids. “A lot of the older boys prefer karate,” he said. “But I kicked out my back a few years ago. This I can keep up with.”

I told him it seemed my speed too. My legs were stiff, my jaw locked, my back tight as a spring. My unmasked pupil was a pinprick, I knew, fearful in the flood of sun. I had only the tiniest window left onto the world. I looked past him to the kids again, who had broken formation and were watching us with disinterest. Even standing still, they looked like they knew how to move.

“Senior classes are at the rec,” coach said.

The first step of tai chi is standing. This I believed I could do, but it turned out I was wrong. On day one the instructor, Brice, realigned me while the rest of the class looked on. “You’re open where you should be closed, and closed where you should be open,” he said. He tugged back my round shoulders, straightened my feet, lightly tucked my chin. The angle of my vision altered, so that I was looking at the flecked linoleum floor. I felt like a giant duck a long distance from water.

“Your posture is your power,” Brice said. “All this time you have been giving it away.” I rankled at this but remembered how even standing at the gas pump that morning had sapped me. “Now,” he said, removing his hands from my hips. “Move.” I took a cautious first step. “Slowly,” he said. “Do not lose the form.”

It was a Sunday afternoon, and people hung around after class to drink greasy coffee from a percolator set up at the back. I was posed near the plastic trestle, trying to maintain my new stance, when a woman began to jog toward me from across the room. She must have been in her eighties but was remarkably spry, slim except for a paunch that filled the top of her high-waisted polyester pants. She had closely cropped white hair and the healthy tan of a peanut. When she reached me, she stretched out a hand and tapped the place where my shoulder met my breast.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m Patty.”

“Don’t move,” she said. I detected a faint accent. “You’re my marker.” She turned and began to jog away. I waited. The place where she had touched me tingled. I watched as she tapped the far wall of the room and lapped back. “I like the way you stand,” she said, still jogging lightly in place.

“Thanks,” I said.

“I’m Hilda.” She extended a bobbing hand. I clasped it and a cheerful ta-da tone sounded between us, like a gem gained in a video game T used to play. She stopped jogging and examined a black band at her wrist with satisfaction.

“What’s that?” I asked. Hilda explained that the device counted her steps and let her know if she was behind her daily goal, instructing her to stand up or walk across the room.

“That is exactly the kind of thing I am looking for,” I said.

“You can have Frank’s,” Hilda said. She explained that Frank was her husband, dead last year. “He never wore the damn thing,” she said when I demurred. “Thought the government was using it to track his movements. But he’s sure as hell not going anywhere now!”

Ha!

We both said Ha at the same time, a sharp exhale like a punch to the air. Got ’em! Got who? It didn’t matter. Hilda flashed a set of small gray teeth. Already, we were friends.

It had been a long time since I’d had a friend—that is, a person attached to me not by authority or need or desire, but plain affection. Hilda was from a small town in northern Germany. She was eighty-two and had come to this country when she was nineteen, because she wanted to be outdoors. “There is no outdoors in Germany,” she said, offering me a plate of cookies she’d made out of what may have been birdseed. “Everywhere, after the war, you were inside.” She had met Frank when he was stationed at the base in her town, and returned with him to Twentynine Palms, which had a sky and a steady food supply. She had no children. “I have curiosity,” she said. “That is enough.”

When Hilda asked how I was, she listened like a bat calling in a cave. She watched my face when I spoke. She asked me what T was in for, and I told her assault and arson. She asked me if he did it and I said yes and no. She poured two cups of black coffee in her yellow kitchen and asked me how I’d lost my eye. I explained about the crying, how I’d damaged the surface of the cornea and bad bacteria had moved in. The ulcerated eye had set a fever in my skull and had to be removed. Hilda pulled my hand to her left breast and squeezed. It gave under my fingers like memory foam. “The right one’s real,” she said.

She’d had the mastectomy at thirty-eight, the same age I’d spent my seventeen-hundred-dollar savings on a single shot of anonymous donor sperm. I picked number 4725 at random and paid extra for the answer to one of the personal questions at the end of the profile, just to have something to tell the kid, if there was a kid, if they asked. Question 3: What is your favorite childhood memory? Answer: Picking tangerines, grapefruit, and oranges from Grandma’s fruit-cocktail tree. The nurse thought that was cute, but later, when I looked it up, I learned it was true, or at least possible, that you could graft different citrus fruits onto the same rootstock and have them flower. Had it bothered Hilda, I asked, to lose a breast at that age, at that time? She shrugged and drank the dregs of her coffee. “Everyone is half,” she said. Then she grinned. “Together we’d make an Amazon.”

Hilda was delighted by my height. She herself was brisk and slight. Though I towered over her, we seemed always to be in step. Hilda walked everywhere she could, and even where she couldn’t. The town had hardly any sidewalks and very little shade. The only people you saw along the road were hitchhikers and bums, or Cambodian salon workers waiting in the brutal sun for the long bus ride back to Barstow. And suddenly there was Hilda, in a broad white hat, walking, her shadow tacked to her feet, sometimes ahead, sometimes behind. At work, my step counter cinched to my wrist, I marched up and down the market aisles or lapped the park on my lunch break, imagining our numbers synced. At tai chi I learned Cloud Hands, Brush Knee, Playing the Lute. Len asked if I’d done something to my hair. I smiled like the Cheshire Cat, my body elsewhere.

T had a job in the kitchen at Ironwood that he liked but the food was terrible. I always stocked up at the vending machines before I sat down. The other visitors were quick to do the same. Five minutes after the inmates came out, the cages were always down to Ocean Spray and gum. This time I had some dried-out chimichangas and a skinny hamburger patty shrouded in a gray bun.

Most of the other people waiting were women, either extra small or extra large, the only sizes left after a sale. Some people saw me in there and thought I was T’s girlfriend; they’d seen stranger pairs. Neither of us gave a damn. Most people never think right off that I’m his mother. We don’t look alike, it’s true. T is half my size for one thing, and Black for another. If that’s how you see yourself, I said, when he was growing up, and everyone wanted a word. It’s how people see me, he said. And he was right. Outside, everybody saw him. Inside it’s the other way around and he gets shit for being mixed.

He came out, head down, eyes up, and I grinned like a goof.

“You look good, Ma,” he said when he sat.

“Thanks,” I said. He did not look so good, I didn’t say. Skinnier than ever, tallow instead of good strong copper. I told him I’d been doing tai chi at the rec. He lifted a brow, the one with the little nick in it.

“That’s you getting out more?” he asked. But he looked pleased. The kid had been nagging me for years to switch up my routine. How come I’m in here and you’re out there and I still got more going on than you? he liked to say. Like what? I always asked, but I knew. Like cooking great flats of lasagna for two hundred guys at a time and finishing another correspondence course.

“I made a friend,” I said. He nodded.

“That’s good, Ma. You got a guy?”

“Ha,” I said. “She’s a she. A little old German lady, would you believe.” He laughed and his shoulders notched down.

“I hope not too old,” he said. “Or too little. Or too—German? Damn.”

“Everything in moderation.”

“What you got for me?” He nodded at the packages on the table between us. The items would inflate a little in the microwave, but it was no Sunday lunch. Still, he looked pleased. He tapped the burger and I got up to nuke it, a minute thirty, ping. He ate fast.

“We get this soy crap in here,” he said, licking a finger. “In disks or tubes or balls depending on the day. Warden got sick of catering to special dietary needs. This way they don’t discriminate against anyone, he says. Just everyone, equally, say I. It takes some serious skill to make it taste like anything, so thank God they’ve got me in the kitchen.” He smiled, crumpled the greasy wrapper and nodded for the next. A minute thirty, ping.

“And a plate for Breezy,” I said when I set it down. I regretted it just as quick. A shutter lowered in his face. Sometimes I leaned too hard on times he was a child. Like that was his life and this wasn’t. He may have looked sixteen when he went in, but he was twenty, and he was a man of twenty-five now. He had gone through a phase, at eight or nine, of asking that I set a plate for Breezy, his imaginary friend. He asked mostly when we had something he liked, Dino nuggets or red beans and rice. I regret I didn’t give him double every time. He ate slowly then, more slowly than any kid I’d known. He’d sit at the table, silent and sovereign as a lord, working the second plate while I tore around cleaning up or making a mess. He said thank you twice and withdrew to his room, which he kept, I thought, as tidy as a barracks. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I guess I just liked having two of you.”

He nodded and unwrapped the steaming snack. “I liked being left alone,” he said. “I liked doing my own thing. With Breezy, I could be alone and have someone to play with. In here, I’ve got no one, and no one leaves me alone.”

“You’ve got me,” I said.

“Thanks, Ma,” he said. But we both knew that nothing went back in with him. When the hour was up, someone would look behind his ears and under his tongue. They’d run their hands across his shaved head, tell him to lift his feet and wiggle his toes. Bend at the waist and cough. He nodded at the last cold package between us. “How about some of that?”

What happened? When he got into the polytech, T moved out, into a duplex at the dusty back ribbon of town. I thought it was shit, cardboard walls and a carpet you could cut your feet on. The windows shook when the training pilots dropped bombs at the base a few miles off. Bam, bam, bam, like birds stunning themselves on the glass one by one. But T liked it, liked living alone. Except he wasn’t. His place shared a wall with another man, an older guy with ropy arms and a round, hard gut who didn’t want neighbors. T’s unit had been empty a long time. This guy had filled up the shared yard with his lawn chair and his tin-can smoker and a bunch of rusted junk he always said he was going to sell. He sat out there all day in his chair, eyes secret behind his sunglasses, patting that belly like it was a pot of gold and someone might try to take it away. T was okay with it. Some people can only share by showing what’s theirs. Things were sour but civil until Bunny came on the scene. Bunny was a runty pit mix that T found skipping along the side of the 62. Like I said, this is no place to walk.

Neighbor guy did not, for one thing, like the dog’s name, Bunny. Like it was making fun, or sissy, either way suspicious. But the dog was whitish with those pink eyes you get on pits and scared as a rabbit when T found him. The dog did what dogs do, which is shit in the yard. He shat and pissed in the yard, and when T was away flipping stacks at Denny’s, he barked. When T got home at eight, the man hurled abuse through the wall. At midnight he turned the TV up and around, so the sound poured through. T went tense and inward. One day, he stopped picking up the shit. Of this I did not approve, and said so. It’s your yard too, I said—who wants a welcome all studded up with turds, and poor Bunny every day having to face it? That dog deserves to see his shit disappear, I said, same as anyone. It went on forever and finished fast. One day Bunny got out and set to racing round the yard, I guess, shitting or barking, and the old bastard killed him. With a bat. When T found the mess, he knocked, socked the man in the doorway so hard his dental plate broke and sliced his tongue near in two. For this the boy would have paid, but he would have paid less.

T is and always has been a person of private rituals, private rules. How we love or bury the dead is our business. That same afternoon he drove Bunny’s body to the scrub a few miles out and set it alight with a can of kerosene. This is a desert and has been for thousands of years. What was the kid thinking? I think his head was just angry sound. The wind picked up, carried a bit of hot ash and lit a creosote. The flame blazed a trail through fragrant scrub and lit upon restricted ground at the edge of the base. It licked an old munitions silo that housed one of the backup generators and consumed it before the sirens came and put it out.

A dog is property. Sometimes you can burn property that belongs to you, but not if it causes damage to the property of another. Then it is arson. If the property belongs to the US military and was once used, however many dusty years ago, to store ammunition or explosives; if the old vet you have bloodied and stunned can speak his practiced hate in court, it might even be considered terrorism. It is not really a crime to kill a dog as you can always say that the dog threatened or attacked or tried to bite.

Did he do it? He did. Was it done to him? It was.

What did the man who robbed me look like? Hilda wanted to know. “Like a thumb,” I said. Hilda grimaced.

“A most unpleasant type.” She put her own thumb and forefinger to her lips and discreetly removed something to her napkin. We had both chosen the chowder, a thick paste of flour and cream interrupted by bits that needed chewing. At her suggestion, we had met at the all-you-can-eat Lost Horse Buffet, though Hilda ate almost nothing.

“What else?”

“Tired,” I said. “Like a tired thumb.” In truth I could not remember much about the man’s appearance, just a blunt head with bluish bags under the eyes. The officer who arrived afterward had frowned at my description. “Anywhere between thirty-five and sixty,” I’d said. “Between five and six feet, in a sweater that was blue or black or brown. Though it may have been a jacket.” The officer had looked at his pad.

“No sign of forced entry,” he repeated.

“No,” I said. “I guess I forgot to lock.”

The officer looked at the disarray of my living quarters: the dishes in the sink, the drawers and cabinets standing open, the bathrobe splashed on the bedroom floor. It was unclear what had been done to me and what I had done to myself. He gave me a number before he left, to call if I remembered anything else. “Anything relevant,” he said at the door. “You’d be surprised by how many people call just to talk. There are different numbers for that.” He looked past me when he said this, over my shoulder, into the empty house.

“Do you ever get the feeling you’re beginning to disappear?” I asked Hilda.

“More like I’m falling apart,” she said, extracting a toothpick from the front pocket of her shirt. I put my spoon down and my hands on the edge of the table. With the greatest depth and detail I could recall, I explained the intermittent vanishings that occurred each day, their onset and progression, my fears and strategies in the face of them. I said I worried that one day I would not come in to work, my workplace of over twenty years, and that no one would notice, that no one would notice if I never left my house again. I confessed that to be noticed, I often wore bright colors or patterns that did not suit me and made my head pound. “It’s like I’m a ghost,” I said. “A ghost in a terrible shirt.” Hilda slid her hand across the table and placed it over mine.

“It’s not so bad,” she said. She looked out the window at a jay heckling a huddle of sparrows picking at a spill. She seemed to be considering something. “You’re how old?” she asked.

“Sixty-two.”

“You’re well past the threshold,” she said thoughtfully. “And you’re tough. I bet you can get up to an hour if you train. Maybe two. The tai chi helps.”

“What?”

“Right now, you’re easy to overlook,” she said. “But not completely invisible. If you focus, though, you can tap in and out.” She pointed her toothpick at me. “Eighty,” she said. “By the time you hit eighty you are totally invisible, at least when you want to be.”

“Ha,” I said. My head felt full of steam.

“Patty,” she said. “I’m not kidding.”

“What are you saying?” The color in the room seemed suddenly to have dialed up. Hilda’s shape softened against the hard, lurid backdrop of the booth. I could feel the table cutting into my ribs.

“I’ll be right back,” Hilda said, getting up. She returned with a swirl of soft serve in a frilled plastic cup.

“Patty dear,” she said. “You’ve been giving away your power.”

“Not anymore,” I said, a little hurt. “My stance is way improved. Brice says so every chance he gets.” Hilda ignored this.

“There is force and there are forces,” she said, salting her ice cream. “Force alone will not get you very far and in fact can cause a lot of problems.” I nodded. This idea was familiar to me from tai chi. “In your life,” Hilda went on, “you may feel that certain things are being forced upon you. For instance, that you are being forcibly erased. This may in fact be true. But it is also true that certain forces, powerful ones, are available to you at these times. Invisibility is one such force. It is just a matter of learning to use it.” With her spoon she swiped off the tip of the perfect swirl before her, placed it in her mouth, and smiled.

How the hell did this thing work? I wanted to know. What were the rules?

“People can still hear and touch you,” Hilda said. “You can’t walk through walls or anything like that, but in your resting state you can generally pass through a scene unnoticed.”

“My resting state,” I echoed.

“It’s like you’re in camouflage,” she said. “Not that army nonsense, which only works on army-colored backgrounds. More like an octopus.” And like the octopus, she said, I could avoid predators and sneak up on my prey.

“But that guy was a predator,” I said, thinking back to the thumb. Hilda nodded.

“You have to choose it,” she said. “If you choose invisibility, it’s a power; if it’s forced upon you, you’re powerless.”

“So that’s it?” I asked. “I just say, I choose to be invisible, and then hey, presto, I disappear?”

“Not quite,” Hilda said. “It takes coordination and concentration. You have to believe it and hold your nerve.”

“And the walking?” I asked, glancing at the band on my wrist.

“Oh, that,” Hilda said. “The walking is just good for you.”

After this, my training began in earnest. I doubled my efforts at tai chi and in the park. Hilda gave me assignments, which I carried out, first fearfully and then with confidence. I remained still in the back office when Chet entered and watched him wipe crud from his nose on the underside of Len’s desk. When he rattled the petty-cash drawer, I scraped my chair back and stood, as if out of nowhere, watching him curdle. I put my headphones on and danced to Tammy Wynette in the frozen-foods aisle like no one could see me, and no one did. I patted a pyramid of Progresso when I passed, silent and bold as a leopard, and watched Len lurch, too late, toward the toppling display. Whenever I met with Hilda, we practiced.

“Let’s get out of here,” she said, nodding at the door of the diner where we’d split a tuna melt and a cardboardy cruller. I looked around for our waiter, a pimply kid in a peaked hat who had asked Hilda to repeat the order several times. “They think you’re deaf, so they become deaf,” she explained afterward.

She stood, crumpling her paper napkin on the plate. “Lunch is on me,” she said. I followed her out of the booth and through the exit into the afternoon sun. I tugged down the brim of my cap and turned to face her.

“Do I have food in my teeth?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said. We turned onto the cracked sidewalk and began the walk back to her place.

“I’ve always wanted to get away with that,” I said.

“There are two reasons for wanting to become invisible,” Hilda said. “To get away from something or to get away with something.” She paused as a cavalcade of motorbikes bawled past. “You never really get away from things,” she said. “Every action returns and is paid for.”

“No,” I said, bristling. “I don’t believe that. I don’t believe there’s justice.”

“Not justice,” she agreed. “The price is always unequal, and very often it is the wrong people who pay.”

I glanced over at her, but she kept her eyes ahead.

“My grandfather,” Hilda said, “was a loud, loose man dishonorably discharged from the Prussian army. It came out much later that he had abused my mother, who in her early life became an opiate addict. At the same time, she became pregnant with her first child, my brother. And he was born with certain infirmities and predilections that were not his and made life difficult for him. At twenty-five he hanged himself. It was shortly after this that I married Frank and went away. I was determined not to pass on any more of this unhappiness, and so I took measures such that I did not have a child. I pretended I could not. I lied. Frank discovered this when it was too late and it hurt him, and over the years he became a loud, loose man. This manner was foreign to him and caused him further hurt, but I recognized it.” I wanted to reach out for Hilda’s hand, but I was afraid suddenly that I wouldn’t find it there. A silence settled between us.

“And getting away with?” I asked.

“We don’t get away with much,” she allowed after a minute. Her pace had slowed, and I shortened my stride. In the distance the mountains drowsed behind a haze of transparent particles that together formed a veil. With the roar of the road at my right I suddenly felt exposed. On our left stretched a vast empty lot for sale. The scrub was fleecy with plastic bags that had blown over from an open dumpster. I stopped and put an arm out to Hilda. She gripped it and hung, weightless. “Patty,” she said. “Tell me. What is the one thing in your life that you would change if you could?”

Hilda had not immediately agreed. Back at her place, under the cool tick of the fan, she had eyed me, wise and wary as a wishing fish. Breaking the boy out of Ironwood was more than a matter of going unseen. There would be armed guards and airlocks, razor wire and high walls, the cage, the keys, the floodlights. Even if we did get in, how did we get T out? If we did get T out, how did we keep him, a man everyone would look for, out of sight, and what kind of life was that? All this, I agreed, was impossible. But so was the chance I had been given. Who knew what else we might yet rescue into reality?

I have never been a hero, I said, and have had no practice with such things. It is late in the day to learn I have a superpower. Frankly, it leaves me at a loss. I could continue to reap my petty vengeance and enjoy the odd free lunch; I could peep in a locker room or listen in on a conversation I’d just as soon not have heard. I could continue to hide. Or I could turn, as I had always tried and sometimes failed to do, to face the thing I loved, and move toward it. Sometimes there’s nothing left to move toward. It is all away, away, away, until you face the wall.

Hilda had come to me at such a time. She had locked me in her sights and run. My child, as I saw it, was walled in on all sides. He could not move forward or back, toward or away from anything. I, his mother, could not do much. I had one eye and one friend, and though I had chosen many things, I had never had any choices. Before me there had been and remained one step and one step only: the next.

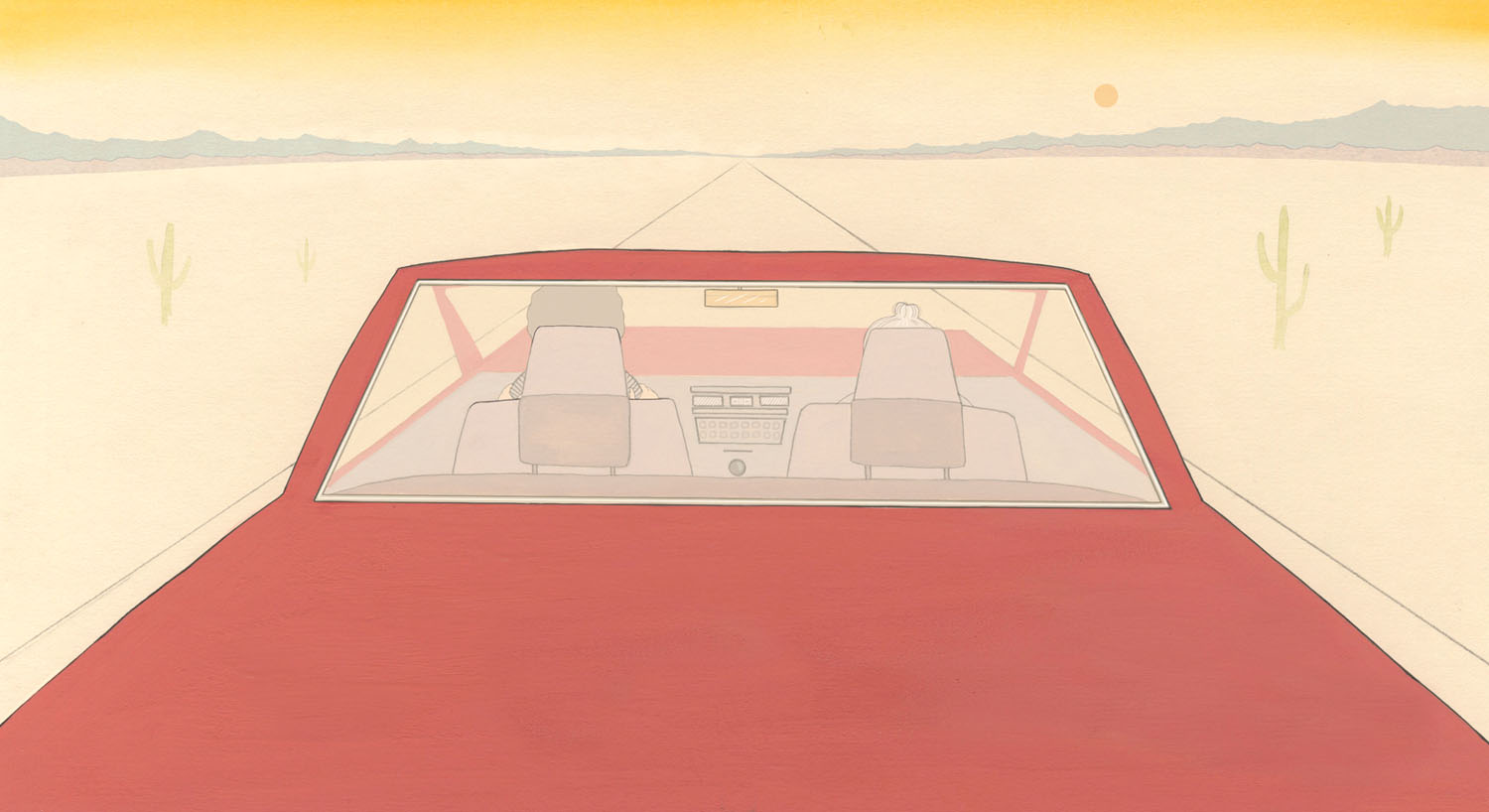

We drove the hundred thirteen miles to Ironwood at dusk. It was a Sunday and the roads were clear. We watched the faces of the mountains change as the day withdrew. Hilda’s car, a beat-up maroon Volvo that smelled like the Yellow Pages, still had a handicap permit on the plate from Frank’s last years in a wheelchair. This, Hilda reasoned, would allow us to hide the car in plain sight.

“Are you sure?” I asked, pulling in to one of the licensed spots in front of the main gate.

“Never even had a parking ticket with this thing,” she said, tapping the blue permit that dangled as well from her rearview mirror. “People stop looking when they see the thing they’re looking for.” She opened the passenger door and dug around in a faded pink backpack before extracting two blackened bananas. “They got a little bruised in there with the bolt cutters,” she said, handing me one. I had a brief vision of us using the fruit to hold up a guard and a laugh popped in my chest. My mouth felt like packed dirt. Hilda ate her banana, closed her eyes and sighed. “Okay,” she said, swinging her legs out of the car.

“Okay, so we just walk in?” Believe it or not, that was, in fact, the substance of the plan.

“Not yet,” Hilda said. “First, we circle the perimeter.”

Ironwood was a medium-security facility enclosed by a high wire fence. As we looped around it, Hilda drilled me again in the essentials. “Keep quiet,” she said. “And don’t look at anyone too long. People are quick to feel eyes on them. Most importantly, hold your nerve. If you become self-conscious, you’re cooked.” I was dressed in tan scrubs not unlike the ones the cleaners wore and had a fake photo ID on a neck lanyard just in case. The getup wouldn’t fool anyone for long but might buy me a valuable minute or two if I slipped into view. Hilda was in shorts and a pilled lilac fleece zipped up to her neck. “I’m a pro,” she said. “I can go long.” I could feel my pulse bucking in the palms of my hands.

“It’s nearly eight,” I said. Our plan was to enter during the shift change, when passage through the prison would be lubricated by the movement of licensed bodies. I knew from my visits that there would be several airlocked passages to navigate, that in a prison you had to wait for each door to close behind you before the next would open. Silent, and, I prayed, unseen, we would attach to authorized personnel like shadows and move with them until we were deep enough inside to find T. Just then, a jaunty tone trilled between us and I jumped.

“Done,” Hilda said with satisfaction, silencing the band at her wrist. “We can go in now.”

The first step was the most difficult, and the easiest. When the sliding doors of the pedestrian entrance opened to release the first of the staff, Hilda and I strode through them into the reception area. The clerk lifted his head from the forms on his desk and looked up. I stopped, and for a helpless second, met his Listerine-blue eyes. They cut straight through me, into the dark that had fallen outside and been vanished by electric light. I felt a brief pain and violent transport, as if I’d been destroyed and survived: invincible. The clerk looked away and the doors shushed shut behind us. We waited, and soon enough they opened again to admit the night shift. Hilda attached to a woman her size with sloped shoulders and spiky maroon hair. I went through about five minutes later, close on the back of a man who smelled like meatloaf. I was aware of the borders of my body as if passing through water instead of air. I moved in step with him up to the desk, through the metal detector and the first gate. I broke off at the staff locker room for women, where Hilda was waiting. I wanted to howl.

Next, the airlocked corridor that passed out of the staff area and into the prison itself. We entered together with two guards and waited for the doors at the other end of the sealed passage to open. Afraid to look at Hilda on my left, I kept my eye trained on the back of my double’s thick neck. He scratched it irritably and glanced over his shoulder. Hilda put out a small dry hand to mine and I held my breath until the exit opened.

It took about an hour to find and reach T’s cell block. We had made it to the right stairwell but the metal door that opened onto the cells was locked. I peered through the narrow window at the top. The cells were on two tiers separated by a mezzanine around a void. I knew T was up there because he’d complained about how the noise below caught and carried, echoing off the concrete. The guard office was positioned directly opposite the stairwell door on the other side of the mezzanine. It had clear sight lines into each of the cells on either side. It was unlikely that anyone would pass through this point again tonight.

“How the hell do we get in?” I said. Hilda didn’t answer. I looked back. She stood in the dim corner of the stairwell, supporting herself with one hand against the wall. She held the other out in front of her and was studying it as if it belonged to someone else. “Hilda,” I said. She looked up at me with blank eyes.

“I don’t know,” she said, her voice small. “I don’t know what comes next,” and it seemed that she was looking past me, through some other locked and final door.

“That’s all right,” I said. I was torn between going to her and reaching T. I looked back through the small window at the guard booth beyond. “We have to get him to come out,” I said, tapping the glass, half-turned toward her. The sound seemed to rouse her. She clenched and then dropped her hand.

“Yes,” she said, though she stayed, mothlike, on the wall. “But how?”

I thought of Hilda’s expression only a moment before. “He needs to see something,” I said. “But not be sure what he saw.”

She smiled at me with real delight and a current passed between us. She crouched down and rifled through the ratty backpack, this time extracting a small plastic flashlight. She clicked it on and quickly off beneath her chin and her features flared in hollow shadows.

“A ghost,” I said. I wanted to laugh but was sure it would sound like something else.

“Wait down there,” Hilda said, signaling for me to descend the flight of stairs. “If he bumps into one of us on the landing, we’re finished.” I went down and waited. Silence. A second more of it than I could bear. As I opened my mouth to query Hilda, to quash the sudden fear that I was now alone, a sound. The click and catch of a heavy door, the scuff of booted feet.

“Jesus,” a man’s voice said after a few moments. He said it softly, to no one, to himself. Again, the opening and closing of the door. Hilda’s head appeared a moment later above the railing and she waved me back up. She gestured, grinning, at a thick piece of card she’d slipped between the latch and bolt as the guard exited.

There was no way of telling where the guard’s eyes were at that next crucial moment: on the cells to the left or right, on the screen of a CCTV monitor or a surreptitious phone, or on the door I was about to crack open and slip through. Hilda handed me the backpack. “I’ll be right behind you,” she said.

And then I was on the grill of the mezzanine. The sounds of sleeping and of sleeplessness hummed up and down the void. I smelled nothing, but sensed the bodies hutched on either side. I had no idea which cell T was in. I would have one chance and one chance only. Whoever I spoke to first would see me. I was afraid, and I shut my eye. All was dark. But in the dark, the faintest flicker of a light. I turned, and the light turned too, a little ahead of me, like the outer limit of the arc of a lamp, where it meets and melts the night.

It was my poor, empty eye, looking once again for its object. Warmth glowed in the withered socket as if someone had set a candle inside. I stepped forward. The faint echo of my foot joined the other hollow sounds. There were a dozen cells on either side of the mezzanine. I swung my feeble lamp to the left, the right, where it burned a little brighter. I followed it blind. At the sixth cell, I stopped.

“T,” I whispered. The blanket on the lower bunk rustled. A sleepy movement gathered itself into a familiar shape.

“Who’s that?”

“It’s me,” I said. A body came forward and stood close to the bars. His body. My boy. The fold at the top of his ears. The dip at the top of his lip.

“Ma,” he said. He said it not so much to me, as to the thought of me, like he was remembering something. But it was enough. I was suddenly aware of the weight of my body on the mezzanine and the thick bars that separated us. T threaded two fingers around one of them and I reached out to touch his hand. He shuddered and withdrew. “Ma,” he said again, awake now. He sounded scared. I pulled the bolt cutters out of the bag with shaking hands. I finally understood that they would never work.

“What the fuck,” said a voice from the top bunk.

“Shut up,” T hissed over his shoulder. “I got this.” He turned back to face me. “What the fuck,” he said.

“We’re going to get you out,” I said. My hands shook and the cutters clinked against the bars. A long murmur ran through the cells on either side. “Take these,” I said. He put his hands up and took a step back into the shadows.

“You’re crazy,” he said. “I’ve got a date. Don’t fuck me up.”

“Hilda is here,” I said. But she wasn’t. Behind me was the void, beside me, the narrow corridor that faced the cage.

“You’re crazy,” he said again. “I’ll lose the kitchen, the yard. I’ll lose my date.” Something fell through my chest. I had not imagined this. I had imagined far too much, and not enough. His body was tense and still, ready to spring.

“Don’t be scared,” I said. “I’m as good as gone.” There was time only to speak, and not to choose my words. “I came to see you,” I said. “I came to—” I stopped. I set the bolt cutters down. I wrapped my left hand around a steel bar and shivered. I reached the right through a gap and held it there in the space of his cell. It looked strange, foreign. After a pause, T came forward and lightly touched my fingers. Heat rushed my throat, my eye. T put his hand in mine and I released my grip on the cold steel, reaching through to cover it. Clasped between my two hands, his own gave off the warmth of a small animal. I swear I felt his heartbeat, quick and light. A minute passed and it slowed to the even rhythm I had carried and that I knew. I squeezed his hand and let it go.

On the way home, I kept my eyes on the paling horizon. I glanced at Hilda in the rearview mirror just as the sun rose above the mountains, and the light seemed to pierce and enter her so that she glowed, the thin skin at her temple and throat transparent, webbed with busy blue veins. I didn’t ask where she had been. She didn’t ask what had happened.

There is a type of cactus that blooms for a single night once each year, and only for the moon. Who knows what joins the flower and the distant rock? There are many things I don’t understand and never will. But some are simple. I took his hand and he let me.

I looked ahead at the road, which seemed to vanish where the earth met the sky. I know of course that the earth and sky don’t actually meet, but in this world, in ours, they appear to touch, and whatever joins them disappears. I lowered my visor against the glare. Already the light was peeling away the shadows. I smiled and turned the radio on. I had been to the vanishing point and could get there again. We were heading straight for it. I gave the car a little gas.