Janie Satterfield does not recalculate. She tries to block out the howling dogs and cats. There’s enough money for a week of food—two weeks if a Christian Youth Group comes in and adopts half the strays. Sometimes she dreams of this: If every Boy and Girl Scout troop in the country adopted one dog or cat, then the number of strays would decrease somewhat. Not much, but a little. If every elementary school in America adopted a mascot. If every hospital. If every retirement home. Janie keeps a notebook of people and organizations that she thinks might help control the pet population in America. If every contestant on a game show, if every person who worried about getting into heaven, if every church and synagogue and mosque, if every prison.

The telephone rings. Janie does not answer. It’ll be one of her volunteers from the Junior League calling to cancel, she knows. Every day, it seems, one of her volunteers calls, faking a cough, saying that she doesn’t want to bring the flu into the kennel area.

The machine beeps. An older woman says, “I hope I got the right number. I’m calling to donate. I can do the five-dollar-a-week program. Just tell me where to send it.” The woman leaves her telephone number and address. Janie stares at the answering machine.

The phone rings again and, thinking that it’s probably the older woman calling to say she misdialed earlier, Janie answers with “Graywood County Humane Society.”

“Yes. I’m calling to offer my donation,” a man says. “I’d like to send a hundred dollars to you.”

Line two rings, then line three. Janie brightens her voice. She says, “That’s so kind of you, sir,” and gives him the post office box address.

And it happens and it happens and it happens. For six straight hours Janie Satterfield picks up the phone, takes donations, and at the end of the day she’s been promised more than a hundred thousand dollars. And she is amazed to learn that a television evangelist, one Reverend Leroy Jenkins, has directed all of his listeners to donate to the Graywood Humane Society.

“I need to write Reverend Jenkins a thank-you card,” she says to herself, still alone without a volunteer. She steps into the kennel area and says to her barking strays, “Maybe we’ll take a photograph of us all and send it to Reverend Jenkins.”

Janie had never heard of this particular television evangelist.

And she’d never heard of Manna Man, working his powers, redirecting.

Manna Man checks the internet. He glances over the Local sections of over three-hundred small-town weekly newspapers to which he subscribes. He takes notes. He categorizes and tries not to make assumptions. The mail carrier detests Manna Man. The mail carrier comes home on Thursdays and asks his wife if she’ll keep quiet should Ben Culler’s house burn down mysteriously one night soon.

The food bank will close in midwinter, right when it needs to be most available. For three years Lloyd Driggers has operated the food bank on Wednesday and Saturday mornings, doling out canned goods, bread, and milk, in large paper bags. He does not question anyone as to hunger or thirst. He makes no judgments. Unfortunately, the donations have dwindled. Area preachers have hinted, then outright demanded, that their congregants give to their own soup kitchens, their own food banks. The preachers have said things like, “Why would you give your hard-earned money and canned yams to an organization that doesn’t even try to save the unsaved? Lloyd Driggers doesn’t offer testimonials. No, he just hands out food. That’s not enough!”

The congregants listened, as congregants do.

Lloyd Driggers’s shelves soon went empty. He spent his savings. He went into his IRA and bought groceries on a weekly basis—$1,000 every Tuesday to help feed the homeless, the unemployed, the working poor. He sold his house and moved into his food-bank space—which used to be a two-bay Gulf service station back in the 1960s. His two children—son and daughter—talked often between themselves about how they would need to take their father in soon, how he’d never recovered from their mother’s long-term illness and subsequent death.

The electricity would be cut first, then the water. When the electricity went, so would his telephone.

“Food bank,” Lloyd says.

“Yessir. Is this Lloyd Driggers?”

“Polk County Food Bank. Lloyd Driggers speaking.”

The man on the other end clears his throat. “I can give five dollars a week. I’d like to do more, but you know my medicine’s costing me. But I can do five dollars a week.” The man asks where to send his money.

And the phone rings again and again until finally Lloyd asks a young girl with a full piggy bank, “How did you get this number?”

“My grandma told me to call. She wants to talk to you next.”

“Your grandmother gave you this number?”

“No sir. The preacher man on TV gave out this number. He told us to send you money.”

Lloyd thinks, Preacher man? He thinks, Maybe all these preachers have understood their wrongheaded actions of the past.

The grandmother gets on the phone and says, “We was watching one them evangelists like we always do on Channel 17 and he says for us to send directly to you. He says it’ll get us one more smile from the Lord.”

“Which preacher?” Lloyd asks. “From around here?”

“No, no, no. The one out in Oklahoma. The one with the hair.”

Lloyd Driggers has never heard of the hairy preacher from Oklahoma.

He has not heard of Manna Man, either.

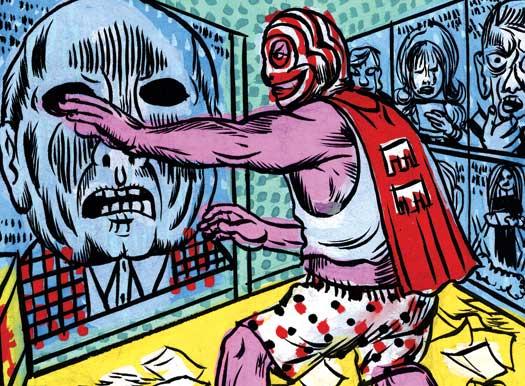

It’s so easily done these days, with high-definition television, Manna Man thinks. This is so much easier than having to attend the tent revivals-feigning a limp, a goiter, a lack of speech, blindness, bad blood, invisible afflictions of the major organs—and finding a reason to touch the evangelist’s throat.

Now he doesn’t have to invest in cheap polyester suits. Now Manna Man can wear his superhero attire at home in front of a bank of Sonys—six across and three high—all tuned to different TV evangelists’ networks.

He works in his boxer shorts most days.

He stocks up on Icy Hot and Bengay to keep his elbows loose, his wrists malleable, his fingers scalding hot.

Herbert Kirby has the paperwork. He’s built one prototype and seeks funding. There are only a handful of scientists and dendrologists out there who believe in him—that his machine can turn pinesap into fresh drinking water without killing off the trees. Herbert Kirby’s even proved that a strong evergreen grows stronger after being “slightly fondled” by his sap-into-water contraption. He likens the process to bloodletting, to frost hardening.

Of course most people think he’s insane. And then there are the bottled water industry executives who understand the consequences of a mass-produced potable water apparatus.

“Make sure it’s in my obituary,” Herbert tells his wife and children. “Make sure it reads ‘This man could’ve saved the entire drought-stricken West Coast and Southeast, but greedy capitalists kept him from being a savior.’”

His relatives don’t believe him. “It’s one of the first signs of dementia,” his forty-six-year-old son Herb Jr. says. “Visions of martyrdom. Visions of grandeur. Visions. There should be some kind of law that no one is allowed to have visions past the age of fifty, especially if said person used to be a car mechanic, pre-computers.”

Herb Jr. works as an optician. He works inside a Wal-Mart, and pretends to know what he’s talking about when customers ask him questions concerning glaucoma, cataracts, and conjunctivitis.

Manna Man understands, though. Manna Man read a human-interest story in the weekly Forty-Five Platter, and studied up on the molecular structure of tree sap. He gazed at Herbert Kirby Sr. standing in front of his machine, which looked more or less like an iron lung, or an old-fashioned sauna.

When Herbert Kirby’s telephone rings back in his workshop—and no one ever calls the number, not even his wife—he picks it up and says, “Yeah.”

Is it really Donald Trump? And later, is it really Oprah, Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, the director of the Kellogg Foundation? If Herbert Kirby only knew. He gives out his address. He says that most of his backers send cashier’s checks. “I’ll send you the first case of sap-to-water, free of charge,” he says. Up until this point he’d only said those words to his dog.

Manna Man will never know the consequences. He will never ask, What were those people doing watching TV evangelists?

At night Manna Man dreams of people skipping in fields, down country dirt roads, down sidewalks, across water. On the horizon, though, there’s always a balding man wearing a checkered coat, his deep-set eyes as hollow and vacant as doughnuts riding a conveyor belt toward a faulty jelly-filler nipple. In the dreams he knows this is his nemesis.

He knows it’s the exact opposite of Manna Man, from a parallel universe. Or from an alternate universe. He can never remember if those two terms are synonymous.

Ben Culler’s father had suffered from psychosomatic pains that left his right arm limp and useless. A religious man, he’d gone to a traveling preacher’s faith-healing revival outside of Decatur, Alabama, walked up on the stage, and spoken into the microphone. He’d said, “I got my arm crushed back at the quarry. It ain’t worked since. I ain’t worked since, either.”

The preacher slayed him in the spirit, right in front of everyone. He shoved his shirt cuff, doused in ether, right into Ben Culler’s fake-lame father’s face. Mr. Culler went down in a pile. And when he regained consciousness he pushed himself off of the makeshift wooden stage built of scavenged pallets, lifted both arms in the air, and said, “Thank you, Jesus, my arms’s been reborned!”

The Alabamans danced and gyrated and praised Jesus and spoke in tongues. They held their arms up high, too. They cried, and begged for mercy, and—if the scene had been captured on silent film—did not act dissimilarly to Turkish Sufi dervishes.

That night at home, Ben Culler’s father raised his right arm up high to his son and said, “You been getting away with way too much, and now Jesus has come to the rescue. I guess God’s telling me that I got to make up for lost time.” He struck his son across the face. His second blow landed hard to the boy’s solar plexus. Ben Culler yelled for his runaway mother. He did not have time to form tears.

His father’s third openhanded blow caught Ben just south of his thyroid cartilage—this may have been from where Manna Man’s powers sprang.

The fourth roundhouse didn’t land. Ben Culler caught his father’s wrist and squeezed it with superhuman strength. His father fell to his knees in much the same manner as when he was slayed in the spirit earlier that day. Before his father expired on the kitchen floor of their trailer, Ben Culler said, “You will not strike me. You will not take my lawn-mowing money and give it to scam-artist preachers. You will not be a vengeful Christian.”

Thus spake Manna Man for the first time.

If the scene had been captured on film with sound, someone would’ve remarked on how his voice sounded like that of a restrained madman. If the scene had been captured on film with digital enhancement, someone would’ve noticed the aura that surrounded young Ben’s palm—an aura that revealed strength, and electricity, and the ability to change wrongs into rights.

Nowadays, if there is a person watching a television evangelist, and the evangelist edges into how his ministry needs money to aid the little half-hearted babies he visited in Haiti, or the lepers in Mongolia, or the heathens of upper Cambodia, or the tendon-lacking children of Zimbabwe, or the green children of Tonga, or the blind babies of Eritrea, or the secular humanists of Lithuania, or the involuntary flinchers of Mali, or the cursed teenagers of Indonesia, then Ben Culler transforms into Manna Man and touches the television screen. The preacher will hear his voice change to a higher octave. The preacher will think he’s saying, “God will reward you in heaven for helping our ministry help the little poor twelve-toed newborns of Paraguay get special-fitted shoes.” He’ll feel a tingle in his throat right as Manna Man transforms the speech into, “God will reward you in heaven for helping our ministry help the Springer Mountain Library Association in its need to buy books published after the Civil War,” and then offer up the telephone number where desperate heaven-seekers can call.

Afterward, the television evangelist moves on. He wonders why the phone bank’s silent. He thinks: Jesus H. Christ, I need to come up with some better needful ailing people of the world.

Ben Culler knows that, if there were a hell, he’d be going. He misused his powers once: He got people to donate him money. Can’t operate without paying the bills, he thought. Can’t get a job at Best Buy and make sure all of the television sets are tuned to different TV evangelists full-time. Can’t work forty hours a week doing something to pay the bills, and another 140 hours funneling money to good causes.

But there is no hell, Manna Man knows. He read all the philosophers for five straight years after his father’s death. He’s read all the religious texts ever written by man.

He’s read all the cookbooks, too, and would one day like to see a world without TV evangelists, so he could settle down with a woman and cook her a nice six-course meal.

There’s a new evangelist—a country-looking preacher—dressed in a checkered coat. Manna Man focuses on the far-right television set in his den. He mutes the other channels. There’s something about this guy: slicked-back real hair, a face that might’ve been used by geology professors when they couldn’t find a decent example of “alluvial formations.” Quiet voice and piercing eyes. It’s not the typical studio setup either—it looks as though this might come out of a basement, or bunker: one man and a cameraman.

“God is punishing America for all the homosexuals we got going here. God has chosen me as one of the few elected to heaven, and he has not chosen the rest of these homos and homo pimps and homo pimp seekers . . .”

Manna Man wonders if it’s parody, if maybe Channel 6 has changed ownership and now runs TV Land. In his downtime—and that’s only an hour at most per day—Manna Man likes to watch reruns of Mister Ed, The Andy Griffith Show, Sanford and Son, and the rest of those programs that his father wouldn’t let him watch back when they were on prime time.

Manna Man waits for this new evangelist to ask for money. Here it comes, he thinks, and sure enough the man says, “That’s why I need all you watching out there to send money to—”

Manna Man shoves his palm on the man’s televised neck. Manna Man thinks to himself, The Women’s Shelters of Eastern Tennessee who need money to continue operation.

“. . . our church here in Topeka so we can continue protesting funerals and bail out our Chosen parishioners who are doing God’s work in this here United States of Sodomy.”

Manna Man pushes his palm harder onto the set. He reaches for the channel changer and flips the next television over to Channel 6 so that this unknown man appears. He shoves his left hand onto the man’s face, and concentrates. Women’s Shelters of Eastern Tennessee, Women’s Shelters of Eastern Tennessee, Women’s Shelters of Eastern Tennessee . . .

The TV evangelist pauses. He looks to his left. He clears his throat. Manna Man knows that he’s come across an adversary with powers that may, indeed, cause the average person to believe in Satan. The evangelist says, “We will be doomed and cursed forever until our so-called leaders understand that the Nazis might’ve been—”

“What an asshole,” Manna Man, says. He’s got his right palm on the top-right television, his left hand on the third-level TV beside it. He reaches with his left foot and toes the Sony to Channel 6 and shoves his sole across the evangelist’s face.

He concentrates. He says, “Women’s Shelter of Eastern Tennessee” like a mantra.

The evangelist pauses, then says, “I know you’re out there, Manna Man. I know all about you. You can’t stop me. I’ve been ordained by God Hisself. He knows all about you and your wicked ways, funneling money to the soulless homosexuals and perverts and the godless and—”

Manna Man lets loose with his right hand, grabs the channel changer, and flips the television set right in front of his boxer shorts to Channel 6. He drops the changer, shoves his right hand back in place so hard that he fears reaching through straight into the television’s innards. Manna Man thinks, This is the nemesis of my dreams. He thinks, This is the heartless enemy I’ve been training for all of these years: part mentally deranged attorney, part egomaniacal evangelist—I’m dealing with . . . the Attornelist!

He leans forward and shoves his penis onto the Attornelist’s mouth. Manna Man focuses. He leans hard, left and right hands touching screens, left foot, penis. There’s silence. Then, finally, the Attornelist muffles out, “Please send your much-needed donations to the Women’s Shelters of Eastern Tennessee,” and gives up the 1-800 number.

Manna Man backs off of his bank of television sets. He looks into the Attornelist’s cavernous black eyes and says, “You will never beat me.” He slips his penis back inside his boxer shorts.

“Manna Man!” the Attornelist screams out. “Man oh man, I hate you, Manna Man. I’ll get you one day! I’ll get you!”

The four screens turn to snow.

For now.

Manna Man crawls to the refrigerator, reaches up, and touches his magnets. They melt onto the floor. He had a feeling this would happen. He’s sapped from the Attornelist.

He opens the refrigerator and pulls out beet juice he’d made earlier in his favorite 12-cup Viking Food Processor with commercial-grade 625-watt induction motor.

Replacing the iron, he thinks. Regaining my powers. Refueling.

A man sits in his recliner, the business end of a .45 in his mouth. He’s already covered the wall behind him in plastic. He doesn’t want to leave a mess for anyone to find. He’s always been that way. Maybe that’s why he’s been named Citizen of the Year twice. Maybe that’s why, up until this point, he’d been able to run a hospice service entirely on local contributions, staffed with two full-time nurses, and caregivers willing to undergo classes, seminars, and biannual evaluations.

But the donations haven’t increased, and the number of elderly people in town, most of them laid off years ago from the cotton mill and fighting lung ailments, has quadrupled. The man needs at least two more nurses, and twice as many qualified caregivers.

He eases back the hammer, and almost pulls the trigger before the phone rings.

It might be his daughter calling. It might be one of the nurses. It might be news that someone else has died and the family needs help with funeral arrangement.

On the other end of the telephone, a woman says she’d like to put the hospice service in her will. She says she’ll send a hundred thousand dollars immediately, and promises the remainder of her estate once she passes on. “To heaven,” she says. “I’ll be going to heaven for sure, now.”

Manna Man’s back on the job, revitalized.