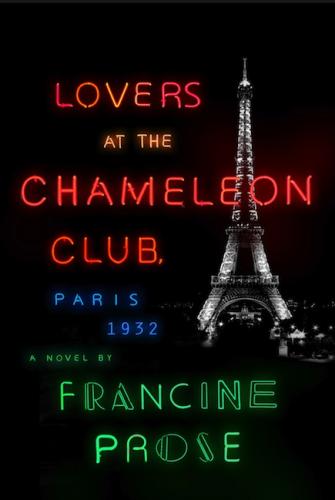

Even casual readers of literary warhorses the New York Times Book Review and the New York Review of Books will recognize the name Francine Prose. She’s written more than a dozen novels dating back to 1973, from Judah the Pious (Atheneum, 1973) to her latest opus, Lovers at the Chameleon Club (Harper, 2014).

In the conversation that follows, Prose and I discuss the Chameleon Club, set in 1930s Paris among its nightlife demimonde, where Pablo Picasso makes a few appearances. We also touch on Bard College, her split career of teaching and writing, the joy of babysitting for her grandchildren, and the movie adaptation of her novel Household Saints.

Birnbaum: What do people call you?

Prose: Francine.

Not Franny?

No.

Because?

The only person that called me Franny was my high-school gym teacher and it left a kind of bad memory.

I ask because people are known to take liberties with names. I wondered how you enforced the appropriate use of your name?

[laughs] With a look.

Right, then the “perp” starts shivering with fright—exposing their insecurity.

[laughs]

Is Lovers at the Chameleon Club a historical novel?

I don’t think of it as a historical novel. I mean, it takes place in history, obviously in

the past, but I think of it as a contemporary novel set in the past. I don’t really like historical novels.

The Hungarian photographer character is based on Gabor Brassai, I think. The main character was a real person.

Violette—she was real, too. And the outlines of her life roughly followed the outline of the book.

And was there a club like the Chameleon Club?

No, there was a club called Le Monocle that was like that club, and in fact, Brassai took a lot of photographs there, but it wasn’t that club.

And Pablo Picasso makes a couple of appearances. In the first one Picasso tells a story—was that actually a story he told or did you make that up?

I made it up.

The second time he appears, he befriends Brassai and suggests he take up illustrating and drop photography.

Brassai did a book of photos of Picasso’s studio—which was basically what he was doing during the war. And a lot of that stuff was true. Picasso did stay in Paris. It was very important to people that he stayed in Paris. And he was in a certain amount of danger. He did shelter refugees. He has painted Guernica.

If the Spanish asked, he would have had to go. But for the morale of the French, it was very important. And then, of course, he didn’t go back to Spain.

There is mention of a German officer asking Picasso if he painted Guernica, and reportedly he answered, “No, you did.” Did you make that up?

No, and the fact that he described his Afghan hound as a dachshund, that’s real as well.

[laughs] But this is not a historical novel?

No.

What is a historical novel to you?

The ones I don’t like spend so much energy telling you what kind of shoes everybody wore and how the streets were paved and what the signage was like that I just lose interest—the characters just seem like the least of it.

Gore Vidal wrote historical novels, and they fall into what you have described.

I don’t like books like—am I saying this? The Girl with the Pearl Earring or… When I was a kid I loved them. I thought James Michener was just fantastic.

I liked Leon Uris [Exodus] also.

Yeah, all those books. No one told me—thank God—that they weren’t serious literary novels. I didn’t know the difference or really care.

What’s currently in the news cycle that has grabbed your attention?

Syria. Global warming insofar as it’s ever in the news cycle. Healthcare. Stuff everybody worries about.

What about incidents—for example, the Donald Sterling brouhaha.

The tape is damning.

So why investigate?

I don’t know. All that stuff is so widespread. So much more widespread than anyone will admit. It’s like these politicians that get caught for whatever they did—I have a theory—like Eliot Spitzer, [Anthony] Weiner—guys in that life have a certain risk-taking behavior that is part of who they are, part of their personalities, and when they get close to something that no one wants them to get close to, then they bust them. Eliot Spitzer, if he had stayed in office, we wouldn’t have had the banking crisis of 2008.

You think?

Oh yeah!

He would have been that aggressive?

He was right about to get those guys. In fact, have you seen the film Client 9, the documentary? It’s fantastic. It’s about Eliot Spitzer, and all these guys—the heads of Home Depot, Bank of America, AIG—all these guys who think that the film was about Eliot Spitzer are saying this stuff that you cannot believe they are saying. Because they don’t think it’s about them. If it was like Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, they would have been careful. These guys just run their mouths and you go, Oh my God.

They do operate in a different reality.

He [Spitzer] was going after Clarence Thomas’s wife because she was making huge donations to the Tea Party—conflict of interest. So whoops, they got him. I am sure it’s just so widespread.

So, why write this book? What was it that moved you?

The Brassai photograph and also finding out that the woman in the photo had worked for the Gestapo. And wanting to find out how a more-or-less moral person becomes that kind of person.

She was normal?

Yes, she was a cross-dresser, but there are lots of cross-dressers.

There were traumatic events in her childhood—

I made them all up.

That she was almost raped?

Yeah, I made that up. The only things I knew were: She had been an athlete, an auto racer, had her license taken away by the government, and had been invited to the Berlin Olympics. She came back, was a spy, told the Germans where the Maginot Line ended, worked for the Gestapo and was assassinated [for being a collaborator].

Wait a minute. She was the only person who knew where the Maginot Line ended? The Germans didn’t already know? Please [laughs].

Anyone could have figured it out.

That would seem to be the first piece of intelligence the Germans would acquire.

She gets credit for it. Anyone could have figured it out.

She lost her license for cross-dressing—which I was surprised was illegal. How much was that law enforced?

I don’t know. But there was a trial, because she countersued to get her license back. The trial was real. And a transcript of that trial exists. So, I don’t know—not very much. Who knows, she crossed the wrong person?

The prefect of police was, as you tell it, still jealous.

I think I made that up, too. It wasn’t the woman in the photograph. Basically, the process was that I had a series of dots, which were the events of her life. I just had to figure out how to connect them.

I’m reminded of the David Shields anthology, Fakes, because of the “sources” that you tapped in constructing the narrative. You had excerpts from a book, personal testimonies, and letters—

They are all written documents except for Yvonne’s [the club owner’s] sections. The rest are memoir, letters, biography. That was by accident. It just worked out that way.

It was effective. What do you think the reader sees when the story is framed with these sources that represent some verisimilitude to factual sources? Readers will see this as a historical novel.

I don’t care, that’s fine with me as long as they read it in the way—I mean, what do I want to say? What’s important to me—the form is as important as the content. So the form of these different narrators—all having a different take on what happened, and a different view of it—that’s extremely important to me. I don’t know any other historical novels like it. Or any other novels like it, either.

Forgive this non-sequitur—have you written a commencement speech?

Yes, I wrote two high-school commencement speeches—one that I gave twice. It was just ten things that I thought they should know when they graduated. Number one on the list was, “Don’t let your mom throw away your stuff the minute you leave.” I wanted the kids to know that. It seemed to me the most important thing to tell them was that at a certain age you don’t think anything is going to change. You think it’s always going to be that way. And that is so not the case. So I felt that someone should tell them that. Not that they would believe me, necessarily.

If you are asked to do it, you take it seriously—there are these kids ending one part of their lives and starting another. And you really ask yourself, Is there anything I wish I knew when I was their age?

That’s not a platitude.

Yes, that’s not a platitude. When I graduated college, our graduation speaker was the Shah of Iran.

Where?

Harvard, Radcliffe. So we boycotted graduation, wore black armbands, blah blah blah. And then we went to the twenty-fifth reunion and Colin Powell was the speaker, and this was right after he had backed down on the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” issue. And my class, the same people who boycotted the Shah, gave the guy a standing ovation. I thought, Hey, what happened in twenty-five years?

Well, what happened was my class, not me, gave Harvard seven million dollars in between. I thought, Okay, they have turned from one kind of person to another kind of person, and here it is. So!

Wow!

I am kind of sorry, now, that I didn’t go hear the Shah of Iran.

This book that was just published—the process is that you spend X number—

5 years.

Five years, you’re done. You now go around talking about it—what’s that like today? As opposed to ten years ago?

I had a fantastic experience last week. It’s a long story—my mother’s best friend—my mother died in 2005—her best friend is the CEO of Marc Jacobs, the designer. And they have a bookstore called Bookmarc. And it’s a great store.

Like Rizzoli?

Yeah, a lot of art books. My son said, “I hate the word ‘curated’ but this gives ‘curated’ a good name.”

Why does he hate that word?

Because you go to a restaurant and they will say, “Our curated beer list…”

Seems like a pretentious appropriation.

I couldn’t figure out what was going on because the place was jammed with the most beautiful, attractive twenty-year-olds I’d ever seen. I’m going, What’s going on here? It turned out my mother and my friend, who is also my granddaughter’s godfather, said to his employees (it’s a huge organization), if they went to the bookstore and bought a book and got it signed, they could come to this dinner afterwards that he was giving. So I signed 200 books for twenty-year-olds. And they were so sweet. I told my friends, I have never been to a bookstore where everyone was young and hot. So that was unusual.

Did they carry Visionaire?

Yeah. They do really well. They sell a lot of first editions and have collectors they deal with. It was great. Other than that, it hasn’t changed that much. I give a lot of readings that are not part of a book tour—colleges, Friends of the Public Library.

Where do you live?

We have a house in Hudson Valley, on the edge of the Catskills. We’re there three-fourths of the time.

Could you see yourself never going to New York?

I have to get my hair cut somewhere.

[laughs]

My doctors are all in New York. For certain basic things I have to be there.

When I consider moving from Massachusetts, I am held back by the superior medical insurance I have. I’m kind of trapped.

Exactly. I have a teaching job, too, at Bard College, which is right across the river. I feel very [knocks on the wooden table] fortunate to be able to have a place in the city and the country. There is nowhere else I want to be.

Bard attracts what kind of students?

My students are geniuses. They are shocking to me, how smart they are. I am always amazed—Bard is like an oasis, really. There is something special going on there.

What is it?

They have a great admissions department. And the president [Leo Botstein] is a visionary. We have the best prison-education program in the country. They are real, degree-granting, rigorous—no journaling bullshit. It’s serious. And we have sister schools in the West Bank, Kirgizstan, Berlin, and a couple other places.

And there are these early high schools—one in New York and one in New Orleans and one in California’s Central Valley. Cesar Chavez’s grandson goes there. The thing I like best is that our president understands and makes very clear that it’s not pre-professional—a place to beef up your resume for Deutsch Bank.

Who endows it? Those don’t sound like revenue-producing programs.

Interestingly, the things that make it great are also the things that move a certain kind of person to give money. And we have this concert hall—a Frank Gehry Fisher Center that has amazing programs. I love it there—I never thought I would say I love my teaching job.

How long have you been there?

Since 2005.

Where have your residencies taken you?

This year, Oklahoma State—

What’s that like?

[makes a face]

C’mon now, do you have an attitude about the American heartland?

No, that’s not true. It was the dead of winter. It was a very hard time to be there. I was at Vassar for a couple of weeks. Where else? Oh, I gave a talk at Syracuse and was in Montreal for four days—various places.

What was your favorite place?

[long pause]

Nothing comes to mind. I like to be in my house. The people are nice and I always—I like the ritual of going out to dinner with the faculty. The people are nice and smart and interesting—I always have a good time.

How do you modulate or filter the amount and kinds of materials you read?

A lot of it is on assignment. Or, if I am teaching, I am certainly reading stuff I have to teach. And then books come to the house—all these galleys. I am writing about this Italian writer Andrea Canobbio—I had to take a train trip and it looked like it might be interesting. It was fantastic. I had never heard of this guy.

That’s the upside of the deluge of books that come one’s way. You do yourself a disservice if you don’t avail yourself of the unannounced, un-hyped books that gather in piles.

My husband is a really good reader in the sense that he—my mother was the same way—if you gave them a stack of galleys that high [gestures to indicate a stack], and said, Look I don’t have time, these just came. Tell me if you see anything good. And both of them could pick out the thing that was extraordinary.

I have become a huge fan of Karl Knausgaard [My Struggle]. And it was because my husband had picked up Volume II, and I said, “We have Volume I somewhere, why don’t you start there?” And I just went nuts. It was so good. He’s a painter and painters get a very bad reputation for not being smart. Untrue. Some of the best readers I know are actually visual artists. He likes big, long, slightly obscure European novels in translation. So he read Peter Nadas’s Parallel Stories. An amazing book.

He doesn’t know how to write a short book.

This time he outdid himself.

What’s your response when you hear people say that there is a lot bad stuff being published?

I couldn’t agree more.

Maybe true, but there is also a lot of great stuff.

I couldn’t agree more. I guess that’s a sign of health in a way. Because there are people who read crap and love it—God love them—and there are people who still read really good stuff. That’s fine with me.

As a professional writer, what’s your view of any changes in the interface of commerce and art? You’ve been at HarperCollins a long time—do you have the same the editor?

No, my original editor died. I have another editor, whom I adore.

Only two editors in your career—is that unusual?

I had one for fifteen year before thats. I don’t know.

Do you hear peers complaining?

A lot of people have the story where the editor quits or gets fired two days before their book comes out. I have a wonderful editor—Terri Carten. I have no complaints. One thing that has changed, but over a much longer time than ten years: When I first started publishing, my first editor at Athenaeum could make a decision about publishing without consulting anyone. If he liked it, he could publish it. Now you need some support in the house before signing up a book. You can champion a book and convince enough people. It’s not like one person is enough. It’s also obviously more corporate than it used to be—for better or worse. And there are new publishers—Melville House, Graywolf.

What do you do besides writing?

In our house, it’s very fox-and-the-hedgehog. I am the hedgehog. My husband is the fox. He does everything. And I really—I don’t—I hang out with my kids a lot. Whenever I can. I beg to babysit for my grandchildren, I see my friends, and talk on the phone, and read.

Your buddy Scott Spencer has a nom de genre.

Chase Novak [for his horror fiction].

Have you thought of doing that?

I have. I would like to write a genre horror novel. It would be fun. He said the funniest thing—he was outted as Scott Spencer the moment it came out, so it wasn’t as if he was hiding—but he said there were certain points where he had to be that person to write what he had to write.

John Banville is in the same situation. When I last spoke with him, he was touting his new Benjamin Black Quirke novel. So there were references to his alternate persona.

Scott is doing his second horror book—the first one was called Breed and the second one is called Brood and is coming out in the fall.

I started Breed and I guess that’s one genre I don’t like.

It was very well written. He’s working on a long novel now. He’s a wonderful writer.

Have any of your books been adapted to the screen?

Household Saints. It was really great. It’s become sort of a cult movie.

Who’s in it?

Lili Taylor, Tracey Ullman, andVincent D’Onofrio. It’s beautiful, really beautiful. They did an amazing job. Blue Angel has been optioned. Showtime has an option on A Changed Man.

I reviewed that book for the San Francisco Chronicle. I am not much of a reviewer. You do a lot of reviews.

I love writing for the New York Review of Books. Bob Silvers is such a great editor. I really feel like I learn something. He is one of those editors whose voice you continue to hear in your head even when you are not working with him. Like, Bob would say I am using too many adjectives and I don’t really need them all.

Who are the literary authorities these days? Who do people pay attention to?

I know people pay attention to the New York Times Book Review. The New York Review, Harper’s—whoever still reads Harper’s. The London Review of Books is amazing.

Do you have any aspirations?

Aspirations?

As in, to do something you haven’t yet done. To achieve some goal that is long-standing that you have put off for some reason.

No. I’d like to have about ten more grandchildren. So, honestly—I am knocking on wood again—I just want more of what I have. Same house, same husband, same life, same career. That would be fine with me.